“This thing about family, now, he said. “It’s an important thing with a lot of people. All kinds of people. And I’ll tell you a group of people it’s important to, and that’s the people who make up the mob. Particularly in New York. You don’t think so? Hard cold people, you think. No. There wasn’t a two-bit gun carrier on the liquor payroll didn’t take his first couple grand and buy his old lady a house. Brick. It had to be brick, don’t ask me why. It’s in the races, national backgrounds, you know what I mean? Wops at the national level, mikes and kikes at the local level. Italians and Irish and Jews. All of them, it’s family family family all the time. Am I right?”

From 361, by Donald E. Westlake.

I had planned to post my review of Up Your Banners this week, but between rereading the book itself, and researching its background, I fell behind schedule. And in the process of researching it, I came across an article I wish I had known about when I reviewed 361, last April, because it sheds some light on aspects of what I think is now widely agreed to be Westlake’s best book written under his own name in the first half of the 1960’s, and one of the best crime novels of any era.

It fell along the wayside for a time, I think, because of the notion, still prevalent in some quarters, that Donald E. Westlake wrote comic capers, and his alter-ego Richard Stark wrote hard-boiled heist stories. It was never that simple, but it was an appealing meme–here’s this guy who writes funny lighthearted criminal romps with sad sack protagonists like Dortmunder, but sometimes he’s this other guy who writes about a cold-blooded killer named Parker.

The implied dichotomy was even turned into a best-selling horror novel by Stephen King, who had named his alter-ego Richard Bachman partly out of homage to Richard Stark, and then borrowed the other half of the name–but it’s hard for me to see how Richard Bachman is any darker or more ‘visceral’ than Stephen King. He’s just a bit harder to pigeonhole, which I assume was the point. Westlake is a far better example of a writer doing radically different things under different names, but under his own name he might do almost anything–and he nearly always did it well.

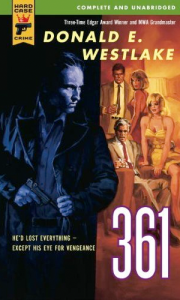

In any event, 361 was hardly ignored when it first came out, even if it was no best-seller. It was reprinted in many countries, many languages, and inspired some of the most interesting cover art I’ve seen for any book, as well as a variety of new titles (though the original title proved fairly durable).

Mexico and Portugal:

British hardcover and paperback:

French Serie Noire and Italian Giallo:

Japan and Germany:

Finland and Sweden (sharing the same publisher, if not the same title):

Sometimes I don’t know what I’d do without the Official Westlake Blog’s cover galleries. But please note, every single one of these editions came out in the 1960’s. This was a forgotten book for quite some time after that, until Hard Case Crime put out the first American paperback edition, which is how I first came to read it, and probably many of you as well.

So now that we’ve all rediscovered the glories of the early hard-boiled Westlake, before the Nephews, before Dortmunder, and quite a long time before The Ax proved beyond all doubt that he could still write the hard stuff under his own name–what do we make of this book, and its odd multi-ethnic pre-Godfather take on organized crime?

Ray Garraty and I have had many discussions here and elsewhere about why Westlake seems determined throughout the 1960’s to not make the mob an exclusively Italian thing. Italian mobsters do show up (Italian by name only, it often seems), but so do lots of Irishmen, Jews, and some guys with generic ‘American’ names. I’ve put forth a variety of explanations for this. Was he trying to avoid offending Italian-American readers, sensitive to the assumption that they were uniquely responsible for racketeering in America? Was it just a convention of the genre as a whole, going back to the old Warner Brothers gangster pictures that had inspired so many crime writers, Westlake included?

Well, it may not have been any of that. I now enter into evidence Exhibit A–a New York Times article, dated April 13th, 1980–Donald Westlake: Larceny and Laughter, by Sheldon Bart (himself a novelist). It was printed right next to a review of Westlake’s latest novel at the time, Castle in the Air, and is mainly devoted to an interview with Westlake (after first mentioning that he was working with Joan Rivers on a script for something entitled A Girl Called Banana).

The reader of this article is informed about the Westlake/Stark thing, and further told that “His style is bright and zingy and his books abound with clever twists and fast dialogue.” Well I guess you’re supposed to say stuff like that when you’re interviewing a writer.

Bart kicks off the interview with the usual “Where do you get your ideas from?” sort of question, only it’s got a somewhat odd spin to it–why does Westlake write so much about crime? I guess Bart never heard of the mystery genre before? Or is this something pre-arranged between them? Either way, he opens by asking “Was your father a criminal?”

Now in Bart’s place, I personally would not have gone there, but instead of taking umbrage, Westlake tells a story–I’d copy/paste it, but you can’t do that with the database I found this on, so I’ll just have to type it out.

Sometime before I was born, my father and mother and another couple were in a speakeasy in New York, and a tall skinny man in a shiny black suit came in, followed by two tough-looking guys with their hands in their topcoat pockets. They headed toward the rear of the place, but as they passed by my parents’ table the skinny man looked at my father and said “Hi Al.” My father said, “Hi, Bill.”

Bill pulled up a chair, sat down and called for a bottle of champagne for the table, on his tab. The two guys with him didn’t sit down or look at anybody in particular. My father didn’t introduce Bill to the others at the table. Bill and my father talked baseball for a while, my father being a very passionate Giants fan, the Giants being at that time a perfectly respectable Major League baseball team in Upper Manhattan and not a lot of padded psychopaths in a Jersey swamp. Then the champagne came. Bill had a taste, and then he got to his feet and said “See you later, Al,” and he and his two friends went away through the door in the back. My mother said “Who was that?” and my father said, “Bill Bailey. I’ll tell you about it later.” But he never did. Now Bill Bailey was a prominent gangster and bootlegger, Dutch Schultz’s right-hand man who took over the Schultz mob for a while after Dutch was killed.

My mother told me this story after my father was dead, so I couldn’t ask anybody any questions. Then later on, after my mother died, I found something very curious in a trunk in the basement. A packed-away trunk is in geological layers, the most recent stuff on top, the oldest on the bottom, and that’s the way it was with this trunk, working on down all the way to my father’s World War I uniform on the bottom. But then under the uniform, out of proper sequence, were a lot of newspaper clippings about the death of Bill Bailey, which took place in 1931. It was a strange death; he walked into a hospital, and was admitted, and by midnight he was dead. The death certificate said advanced pneumonia, but doctors I’ve talked to tell me nobody walks around like a healthy man seven hours before dying of advanced pneumonia. Anyway, those are the only newspaper clippings my father ever saved, and he went out of his way to hide them, and that’s all I know about it. Except that for a while my father was a bookkeeper for a sugar company, and I know the bootleggers needed a lot of sugar in making their booze, so maybe that’s the connection. Anyway, the mysteriousness of it, the completely impenetrable aura, if that’s what I mean, has occasionally gotten into my books, particularly the early ones.

Hard to say how much research he did into the history of organized crime in response to this–some, certainly–but based on the bit of research I did via Google (hardly an option for him back then), I think we can say that Westlake never made much attempt to master the subject. William ‘Bad Bill’ Bailey was the right-hand man of Vannie Higgins. Higgins was a bitter rival of Dutch Schultz during the Prohibition era, who exchanged shots with The Dutchman on more than one occasion, and was eventually fatally wounded (perhaps by Schultz’s men), several years before Schultz himself was killed.

There’s not a lot of information about Bill Bailey out there. That’s him standing (appropriately enough) to the right of Vannie Higgins, in the photo up top–in a dark topcoat–Higgins is in the trench coat. And before you ask, the song “Won’t You Come Home Bill Bailey” is not about him. I checked. That must have been another Bill Bailey. But if there’s one thing we can know for dead certain, it’s that this Bill Bailey couldn’t have taken over for Dutch Schultz, because he died (of natural causes or otherwise) in 1931, and Schultz was famously (or infamously) murdered on October 24th, 1935. Westlake wouldn’t have needed Google to find that out. He didn’t give a damn. He was writing fiction, not history.

So why all the mob stories? Because to him, the point of that little anecdote about his dad was that all your parents have secrets, lives they lived before you were even born. Mostly those secrets stay buried, though if they live long enough, maybe they’ll tell you some of them (my dad’s shared some real corkers with me in the last decade or so–no ganglords so far). Westlake lost his father when he was still a very young man, his mother not long after, and there were questions he was never going to get to ask them, answers he was never going to find.

He’s writing in a genre where stories about organized crime are de rigeur, but how does he put his own unique spin on them? His most important literary role model, Dashiell Hammett, wrote mainly from the detective’s point of view–saw criminals only from the outside, though he had the advantage of actually knowing a whole lot of them from his work as a Pinkerton.

His more contemporary influence, Peter Rabe, used mob stories as a way of dissecting character–strong willed, resourceful, but ultimately chaotic individualists, striving for power in an organization, and eventually undone by a combination of hubris and emotional vulnerability. Psychological case studies, from a future psychology professor. The only ones who survive are the ones who just give up the game they’re playing before it’s too late, let go of their ambitions, learn how to live for the sake of living.

Westlake probably never made the acquaintance of any real crooks until he started getting fan mail from them, mainly for his Parker novels–in the article I quoted above, he says he got a letter from one guy who was about to start serving a long stretch in prison, and he was hoping Westlake could fill a few holes in his collection of Parker novels, because he wanted to take the whole series into the joint with him. Westlake doesn’t say if he provided the books–the guy only needed two of them. I’m guessing Westlake helped him out.

But while he clearly got some ideas from these letters–I see references in that interview to missives he received from criminals that almost certainly inspired Help I Am Being Held Prisoner and Bank Shot–his knowledge of the criminal class remained primarily second-hand. He maintained a certain distance between himself and his subject material, which was certainly prudent. And he had to start writing crime novels before he could get fan mail from criminals–361 can’t be based on correspondence he hadn’t received yet.

No, he was mainly working from pre-established fictional models–Hammett, the Gold Medal novelists (Rabe, Jim Thompson, Chester Himes), the Warner Brothers pictures of the 30’s and 40’s. And many others. But he’s going to make this old subgenre new and personally relevant, by linking it up to his belated discovery that his father was connected, however peripherally, to the world of organized crime. As so many Americans were, during Prohibition. Perhaps the majority, in the sense that most Americans never really accepted the 18th Amendment, went right on drinking what they damn well wanted to drink, and came to admire many of the colorful characters who supplied their illicit hooch. That goes on to this very day, of course–but never to the same extent seen in the 20’s and early 30’s.

The Italians (chiefly but not entirely Sicilians) were gaining ever-greater power in the gangs of that period, because of the syndicate subculture some of them had brought from the old country, and the fact that it was harder for them to assimilate into the mainstream (the most talented individuals from other groups would more often find other outlets for their talents).

But they were joined by German, Russian, and Eastern European Jews (who also had assimilation issues), the Irish (troublemakers wherever we go), and quite a few poor WASP’s–basically every group that was on the outs with society in some way. And that’s a lot of people. And while some members of these groups would fight Italian control, others were quite happy to go along with it, as long as they got their slice of the pie. The ethnic boundaries were never that clearly drawn, and certainly not back in those days.

At their peak, these racketeers were so politically and socially well-entrenched that Vannie Higgins could land his private plane at a state prison in Washington County, New York–and have a nice public tete-a-tete with the warden there, an old friend of his. This was widely reported, and the warden didn’t even lose his job. You absolutely could not trust the police and many other authority figures of that time, so many were on the payroll.

That’s why Elliot Ness and his men were called The Untouchables–because a cop who couldn’t be bought was such an oddity. But in the end, the Prohibition mobsters made themselves too visible, too obvious a source of public corruption, and a lot of them went to prison, often on tax evasion charges.

The most important Chicago organization was called The Outfit–and was heavily Italian, but to Westlake that was never the point–the point was that it supplied things people wanted–liquor first, then gambling, prostitution, etc–and was run like a business–and as time went on, a modern corporation.

In 361, you see a war between the old-era Prohibition guys getting out of jail, and the new corporate-style mobsters, who have assimilated more into the mainstream–and learned to keep out of the public eye most of the time. Ed Ganolese, introduced in The Mercenaries, is the boss of this faction in New York–and Eddie Kapp, the biological father of 361’s protagonist, Ray Kelly, is the old-school boss who takes him down, with Ray’s help.

From this one glimpse into the elder Westlake’s past, we see the genesis of these early books. Westlake imagining an alternate family history, where his dad had been a smart lawyer who got enmeshed in mob politics, and was good friends with Eddie Kapp. Westlake himself, who we gather didn’t look much like his dad, could ask himself what if his father was somebody else–what if the mobster buddy was his true genetic forebear–though Ray makes it clear that he considers Willard to be his father either way.

The most powerful emotional moment of the book comes between Ray and Willard Kelly, very early on–Willard meets Ray in the city, after a long separation, and they’ve clearly missed each other a great deal. “We cried like a couple of women, and kept punching each other to prove we were men.” It’s hard not to think this is based on a reunion between Westlake and his father after he got out of the Air Force. And very shortly before Albert Joseph Westlake died.

Westlake had powerful but mixed feelings about his father, and fathers in general–he never forgot the way his father had intervened on his behalf when he was arrested for stealing a microscope at college, pulling every string to get the case squashed, and his record scrubbed clean. And then, as he wrote in his unpublished memoirs, his father apologized to him for not being able to better provide for him. Love mingled with gratitude and guilt–always a heady mixture.

And always behind that–in just about every parent-child relationship that ever was–is that underlying realization that comes upon us as as we mature, if we mature–that we never really knew our parents completely. That they used to be these other people, who will always be strangers to us. That they had their own identities, completely apart from being ‘mom’ or ‘dad’, which most of us ignored until it was too late.

And the less we know about our parents, the less we know about ourselves. Many an autobiographical work has been devoted to someone’s quest to better understand his mother or father, in order to achieve self-understanding–the current President of the United States wrote a rather good one. I wonder if Westlake read it?

So maybe a good alternate title for 361 would be Schemes From My Father–or fathers, plural, since Willard Kelly wasn’t as innocent as he seemed. We never get to hear Willard’s side of the story–just like Westlake never got to ask his father what his connection to Bill Bailey was. Some mysteries are never completely solved, even in a mystery novel. Let alone a blog about mystery novels.

Still, I think I’ve stumbled across a big piece of the puzzle here. Westlake wrote about organized crime the way he did in the early days because he didn’t see it as this separate exotic world, cut off from the rest of us, the way many others in the genre depicted it as, full of strange codes and foreign rituals–its roots might be foreign, but its genesis was entirely American and familiar–it was made up out of our fathers and uncles and brothers and cousins (and occasionally Nephews).

He knew that perfectly ordinary decent ‘respectable’ people had roots in that world, whether they cared to know it or not. He went digging for his past in an old trunk in the attic, and he found out some things his father maybe didn’t want him to know–or maybe he did on some level, and that’s why he didn’t just destroy those newspaper clippings. It’s hard to let go of your past–it’s like turning your back on a part of yourself.

He also wanted to point out that dishonesty was not something unique to criminals–there are other kinds of ‘Outfits’ in the world, many of them quite legal, their methods sometimes even more contemptible. The corporate world was something he despised on a very deep level, but he also knew it was unavoidable. He may not have been an employee of any corporation, but he still worked for them. Publishers, movie studios, etc. Increasingly all just one big conglomerated mass of mendacity and mediocrity.

To be sure, that was part of the point Mario Puzo later made with The Godfather–the book that at least temporarily made non-Italian mobsters seem quaint and old-fashioned, and that was about the time Westlake started writing more about the mob as a specifically Italian thing. The fashion had changed, and he’d mainly gotten mafia stories out of his system anyway. It wasn’t going to be a major thing for him–he was about the independent operators.

And this is a sort of symbolic rebellion against his father, who may not have been any kind of mobster (maybe he and Bailey just knew each other from school or something), but who had been a loyal company man all his life–a cog in a machine, never really getting anywhere, never making it, doing everything he could to see his son got a better shot than he did. And his son was grateful, but he had to try it his own way–he didn’t think his dad’s way had worked out so well.

At the end of 361, Ray Kelly is alone–his family erased from existence–but he’s his own man. He’s learned the whole truth about himself, and he can build on that, if he wants. That’s very much how it was with Westlake himself in the mid-1950’s, with both parents dead, and a younger sister he seems to have never been close to. Like Ray, Westlake is going to have to make a life for himself–standing on the shoulders of those who came before him. But free to make his own mistakes, instead of just repeating theirs.

And standing on Albert Westlake’s shoulders, Donald E. Westlake became his own man, never holding a steady job for most of his adult life, making his living a book at a time, which wasn’t an easy way to live, we can be sure. He was never 100% secure, never had the kind of big seller that makes a writer’s fortune. But he was free. Of everything but the past. Nobody’s ever completely free of that.

Case in point–there was another group involved in organized crime–Kapp, talking about how it takes three generations for the children of poor immigrants to become ‘respectable’, mentions them–

This is about Cheever again. The Negro. He wants to be respectable too, same as everybody else. But he can’t be, and it don’t matter how many generations he’s been here, you see what I mean? So he’s liable to wind up in the organization.

Already, Westlake was feeling some curiosity about African Americans–they keep turning up in 361, and other novels, but just as minor characters–he’s nibbling around the edges of something. He’s got some opinions on The Race Question, but he’s not quite ready to share them.

In our next book, he’s going to tell us what he really thinks.

(Addendum to the addendum–I should have checked earlier, but according to the New York Times, William Bailey died of pneumonia on December 1st, 1934–not 1931. Westlake got that wrong too. He still died before Dutch Schultz. Westlake really didn’t give a damn about the fine details of mob history.)

That happens with all of us, dark secrets of the others attract us like nothing else. And only artists can work with these secrets, digging further and further.

You wrote yourself that almost every one in US in that time has some connection to organized crime. Hardly anyone could make a proper research of Mafia, when it was all hush-hush, and on the day-to-day level you couldn’t just come up to some mobster and ask him questions. That left only one way of research – with your own imagination.

There was similar situation in Russia, when almost everyone had a close friend or a relative who had been in prison or in Gulag. Only you couldn’t write about it, and even later when Gulag was over, fiction rarely pursued life of a criminal, sticking with the law and its side. That was safer for all.

Well, I myself haven’t done enough research to have any clear idea what percentage of Americans were involved with organized crime during Prohibition–certainly much more than half, if you count just drinking illegal beer and booze. If Westlake’s parents were in a speakeasy (ie, before the 18th Amendment was repealed), they knew they were breaking the law, but as Westlake has a very law-abiding character say in the next book on our list, when the law ignores common sense, the common people ignore the law.

Actually working with gangsters is something else again, and it does sound like Joseph Westlake may have had some kind of connection, but that’s all we can say on the basis of a chance meeting and a few newspaper clippings at the bottom of a trunk. And again, he and Bailey could have known each other when they were young, and maintained the relationship. If Westlake Sr. had been seriously involved, you’d expect him to have been more prosperous. Not waiting out a heart attack in a cheap hotel, drinking cheap liquor.

I wouldn’t expect Westlake to interview mobsters, but he certainly knew how to look up old newspaper articles–Ray Kelly does that in 361–uses the New York Times index at the library. I’d assume Westlake did some of that, and it’s possible his memory of what he learned got cloudy over the next two decades or so. But how he got the idea Bill Bailey worked for Dutch Schultz, and succeeded him—-when he and Schultz were enemies, and he died about a year before Schultz–that’s a pretty big error. Indicative to me that Westlake, who could do very good research when he felt like it, simply wasn’t that interested in the mob, as such. To him, it was a good pretext for examining certain aspects of family and society.

It would be a positive sign for Russia if people felt free to write about that kind of family history. Australians now brag about having ancestors who arrived there by way of penal transportation. That was considered a shameful thing, well into the 20th century.

Thanks to DNA testing, white Americans are just now coming to terms with the fact they may have ancestors who arrived here on slave ships–some family reunions are getting a lot more interesting. The white descendants of Thomas Jefferson are now accepting black descendants as family, after a long period of denial (though some still deny it was our third President who was responsible for this). It’s long been a source of pride to have Native American ancestry. Of course, that’s hardly the same thing as being descended from a felon. But I think most of us would think it was exciting to have gangsters in the family tree–as long as they aren’t too recent.

I myself have (or rather had) a great uncle who reportedly shot prisoners in the Irish Civil War–he fled the country afterwards, to avoid being assassinated. He was on the pro-treaty side (it’s a long story). That’s something most Irish people didn’t want to talk about for a long time after it happened. Now it’s starting to open up more. Maybe with this kind of thing, it works roughly the way Eddie Kapp said about immigrants–three generations to become respectable. Probably takes more than three with some things.

What a dynamite discovery. Thanks for sharing both the info and your no-doubt on-point analysis. Great work all around, and much appreciated by this reader, who has always wondered about what drove Westlake.

A whole lot of things, I’m sure. And most of all, the need to keep paying the bills.

361 feels so personal, though, so intense–more than many of his other novels, certainly those written under his own name. And again, I think that’s why it was a forgotten book for a long time–it didn’t fit what people had come to expect from him.

In 1980, when he did this interview, he hadn’t written a non-humorous crime novel in six years–and that was credited to Stark. Even the Parker novels generally have more humor in them than 361. It’s an unusually grim and downright morbid piece of work for him–maybe the Tobins come close, but at least Tobin gets to go home to his family and that wall he’s building.

Of course, when he did this interview, he was probably working on Kahawa–but I think even that’s more humorous than 361. He didn’t really top 361 until he got to The Ax–which also stems in part from memories of his father.

This and The Hunter were his first masterpieces, and it is interesting to know more of this one’s genesis. Anyway, glad you enjoyed it.

This and The Hunter were his first masterpieces

Wholeheartedly agree with you.

Now, it seems, it’s been written and told about everything, it’s tough to tell something new and surprise the reader. Memoirs of the daughter of a serial killer? Check. Gangster tales from molls and dolls? Check. Prison tales from tough guys? Check. I think the rise of mobster stories was in 80-90s, then it began to slow down.

It comes and goes, the gangster story–you can trace it back as far as D.W. Griffith’s Musketeers of Pig Alley, if you like. What changes is the way it’s told. Serious or funny? Sympathetic or evil? Foreign or domestic? The one thing you almost never get is a realistic depiction of organized crime. And you certainly don’t look to Westlake for that.

Hi,

Did you know that the French Serie Noire were sometimes terrible translations?

Some new translations of Westlake are available in Rivages Noir now. That’s good for French readers.

PS : Have a look at Guy’s blog here: https://swiftlytiltingplanet.wordpress.com/2013/07/14/kinds-of-love-kinds-of-death-by-donald-westlake/ (if you don’t know it yet!)

Sadly, I could not possibly know that, since my repeated efforts to learn French have all ended badly. I can fake it with the best of them though, as perhaps you have noticed. 😉

Not surprising, in any event–that kind of literature tends to get short shrift in all cultures–they wouldn’t shell out for the best translators–or even if the translators were okay, they’d be expected to get the work done ASAP, and good translations take time. Now that this type of fiction has become ‘classic’, they’ll take more care getting it right. But Gallimard was out to make money. I mean, they didn’t even pay for cover illustrations most of the time.

And weirdly, I look at those plain black covers with the ugly yellow lettering, and all I can think is how cool they are. Westlake seems to have felt the same way about it. I think he’d rather have gotten paid right away back then for the badly translated books than wait decades for good translations.

I wish more homegrown French crime fiction was available in English translation. Of course we have the acknowledged masters–Simenon, etc–detective fiction. But Jose Giovanni? Fuhgeddaboudit. I know he was a Nazi collaborator and all, but I’d still like to read some of his stuff.

Thanks for the link. I’ll check it out now.

You’re right about the translation: it was considered as second zone literature. (in French we say “roman de gare”, literally “train station books”)

About the covers: French editions of books have often covers that are simple or sober. Most of the time I don’t like American or English covers for literary fiction (those pulp covers are excellent). It often seems over the top and they deserve the books because they plant an image of it in your head that has more to do with misplaced marketing than actual literature.

About crime fiction in France, have a look at this festival. http://www.quaisdupolar.com/en/the-festival/

For now, the writers expected there are:

ALTARRIBA et KEKO (France), Jean-Philippe ARROU-VIGNOD (France), Edyr AUGUSTO (Brésil), Saul BLACK (Grande-Bretagne), Stéphane BOURGOIN (France), Fabrice BOURLAND (France), Michel BUSSI (France), Shannon BURKE (USA), Max CABANES (France), Horacio CASTELLANOS MOYA (Salvador), Maxime CHATTAM (France), Sandrine COLLETTE (France), Michael CONNELLY (USA), Maurice G. DANTEC (Canada), Didier DECOIN (France), Kishwar DESAI (Inde), Pascal DESSAINT (France), DOA (France), Jacques EXPERT (France), Caryl FÉREY (France), Nicci FRENCH (Grande-Bretagne), Alain GAGNOL (France), Santiago GAMBOA (Colombie), Sébastien GENDRON (France), Elizabeth GEORGE (USA), Sylvie GRANOTIER (France), John GRISHAM (USA), Jake HINKSON (USA), Anthony HOROWITZ (Grande-Bretagne), Yasmina KHADRA (Algérie / France), David KHARA (France), Richard LANGE (USA), Alfred LENGLET (France), Jérôme LEROY (France), Paulo LINS (Brésil), Attica LOCKE (USA), Sophie LOUBIÈRE (France), Val McDERMID (Écosse), Ernesto MALLO (Argentine), Ian MANOOK (France), Dominique MANOTTI (France), Elsa MARPEAU (France), Nicolas MATHIEU (France), Michaël MENTION (France), Denise MINA (Grande-Bretagne), Dror MISHANI (Israël), Patrick MOSCONI (France), Mike NICOL (Afrique du Sud), Gert NYGÅRDSHAUG (Norvège), Leonardo PADURA (Cuba), Vincent PERRIOT (France), Elena PIACENTINI (France), Giani PIROZZI (France), Jean-Bernard POUY (France), Michel QUINT (France), Daniel QUIRÓS (Costa Rica), Ian RANKIN (Grande-Bretagne), Christophe REYDI-GRAMOND (France), Sebastian ROTELLA (USA), Laurent SCALESE (France), Luis SEPÚLVEDA (Chili), Tom Rob SMITH (Grande-Bretagne), Gunnar STAALESEN (Norvège), Emily ST JOHN MANDEL (Canada), Nicolas SURE (France), Paco Ignacio TAIBO II (Mexique), Franck THILLIEZ (France), Diego TRELLES PAZ (Pérou/France), Yana VAGNER (Russie), Emilio VAN DER ZUIDEN (Belgique), Benjamin WHITMER (USA), Don WINSLOW (USA)…

That’s a festival of names to look up! 🙂

That’s a lot of work for somebody who still has to finish his review of Up Your Banners (which is proving a challenge), but I do appreciate the information.

You’re right about cover art (or lack thereof), of course–I’ve seen this about French books at the library I work at, though having been very briefly to France (Strasbourg) when visiting friends in southern Germany, I do remember seeing many an illustrated cover in the excellent bookstores there–perhaps the style has changed.

A bad illustration is far worse than no illustration at all; this I fully agree with. But American crime publishers often commissioned some truly amazing cover art, that enhances the work overall. You can say it colors your perception of the book–or that it sets the mood. Anyway, the book is either good or not–the worst art can’t spoil when it is, and the best can’t save it when it’s not.

> And before you ask, the song “Won’t You Come Home Bill Bailey” is not about him. I checked. That must have been another Bill Bailey.

In fact, it’s about when a Chicago sportswriter who wrote under the name Bill Bailey moved from one newspaper to another. His real name was Willam Veeck, and his son Bill Jr. was the master showman who at various times owned the St. Louis Browns, Cleveland Indians and Chicago White Sox. Bill Jr’s most famous gag was to hire a pinch hitter who was 3 foot 7 inches tall, and so absolutely impossible to throw strikes to.

Eventually, the sum of all human knowledge shall be contained here.

Oh wait, that’s Wikipedia. 😉

I think the novel has a good start but when Kapp enters the scene the plot goes down the drain. It is just too unbelievable, both as to how the mob is pictured but especially as to how the familiar story is complicated. It is apparent the effort by W. to give depth to his protagonist and that differentiates him from any hard-boiled hack, but it is not enough.

I would love to know what you consider a believable mob story. It has never been about realism (people don’t want to know how boring these guys are most of the time).

I just watched The Irishman, and didn’t believe one minute of it–even the parts that are historically documented (Scorsese really got stuck in that offscreen narration thing after Goodfellas, didn’t he?) Good to see the gang back together again, though (the digital de-aging did not work). Some nice moments.

361 isn’t trying to be a realistic take on the mob. It’s using the tropes of genre (augmented with actual research, which you don’t seem to have ever done) to make points about human nature, but a lot of the points made (like mobsters coming from outsider cultures) still ring true today).

You can only fault a writer for failing to hit the targets he aimed at. This nails every single one.

And speaking of hacks, if you keep spamming my blog, I’m going to introduce you to The Ax. 🙂