“The thing is,” Andy explained, “when I feel I need a car, good transportation, something very special, I look for a vehicle with MD plates. This is one place where you can trust doctors. They understand discomfort, and they understand comfort, and they got the money to back up their opinions. Trust me, when I bring you a car, it’ll be just what the doctor ordered, and I mean that exactly the way it sounds.

Looking dazed, Anne Marie said, “You people are going to take a little getting used to.”

“What I do,” May told her, sympathetically, “is pretend I’m on a bus going down a hill and the steering broke. And also the brakes. So there’s nothing to do but just look at the scenery and enjoy the ride.”

Anne Marie considered this. She said, “What happens when you get to the bottom of the hill?”

“I don’t know,” May said. “We didn’t get there yet.”

It wasn’t a car that came for Max forty minutes later, it was a fleet of cars, all of them large, all except his own limo packed with cargos of large men. He couldn’t have had more of a parade if he were the president of the United States, going out to return a library book.

His own limo, when it stopped at the foot of the steps from the TUI plane, held only Earl Radburn and the driver. Earl emerged, to wait at the side of the car, while half a dozen bulky men came up to escort Max down those steps, so that he corrected that image: No, not like a president, more like a serial killer on his way to trial.

The president image had been better.

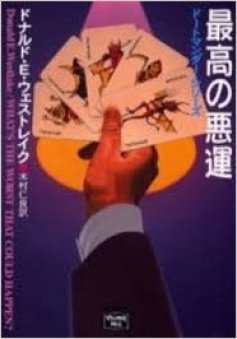

It came up in the comments section last time, and bears mentioning here–this novel marks the total reversal of the original Dortmunder/Kelp dynamic. In the first three novels, Kelp brought Dortmunder a crazy-sounding job, the job would go sour, and Dortmunder would blame Kelp, call him a jinx. Then work with him again in the next book.

This couldn’t go on indefinitely, so in the next five novels, somebody else brought Dortmunder the job, or, in the case of Why Me?, the job was a simple one-man burglary that suddenly got very complicated. Kelp might be help or hindrance, usually both.

This book starts with somebody bringing Dortmunder a job; a simple two-man burglary, that suddenly gets really complicated. The billionaire Dortmunder is ostensibly robbing robs Dortmunder instead. Takes a supposedly lucky ring May gave him right off his finger. Humiliates him. Dortmunder wants his lucky ring back. He needs help. He has to track down this billionaire and take that ring off his finger personally, to undo the insult. It’s about self-respect, not money.

So he calls Kelp in, and Andy is atypically hesitant–this job sounds crazy! Dortmunder has to sell him, and in the end it’s not loyalty that makes him agree–it’s that Dortmunder, who has been the real jinx all along, is suddenly himself a good luck charm. Now that he doesn’t have the ring. Now that he could care less about money, he’s making money hand over fist. Everybody wants to work with him now. He’s got the Midas Touch.

First he went back to Max Fairbanks’ house in Carrport LI, and pillaged it, all by himself. Then he got together a four man string to hit an apartment in a theater/hotel complex Fairbanks owns. Everybody made out great from that score. But both times he missed Fairbanks, and Fairbanks is wearing the ring, never takes it off, because it bears his corporate symbol, the I-Ching trigam Tui, and he believes it will bring him good luck (which he’s already enjoyed an obscene amount of). Dortmunder has to catch him offguard somewhere. And the guy has to testify before congress, so he’s going to be staying at a little place he’s got in the Watergate. Because where else, right?

Dortmunder and Kelp should be able to handle that gig by themselves, but they don’t know Washington. Affordable GPS devices are not a thing yet, even for Kelp. They need a guide. Fortunately, Kelp just hooked up with the very recently single Anne Marie Carpinaw, daughter of a 14-term Kansas congressman, abandoned by her husband at the Fairbanks hotel in Times Square. She knows our nation’s capital like the back of her lovely hand. And is ambivalent about it, as she seems to be about nearly everything in her life, Kelp included. Well, when you get right down to it, everybody is ambivalent about that town. Though it can seem awfully stuck on itself.

“The George Washington Memorial Parkway? They really lean on it around here, don’t they?”

“After a while, you don’t notice it,” Anne Marie assured him. “But it is a little, I admit, like living on a float in a Fourth of July parade. Here’s our turn.”

There was a lot of traffic; this being Sunday, it was mostly tourist traffic, license plates from all over the United States, attached to cars that didn’t know where the hell they were going. Andy swivel-hipped through it all, startling drivers who were trying to read maps without changing lanes, and Anne Marie said, “Now you want the Francis Scott Key Bridge.”

“You’re putting me on.”

“No, I’m not. There’s the sign, see?”

Andy swung up and over, and there they were crossing the Potomac again, this time northbound, the city of Washington spread out in front of them like an almost life-sized model of itself, as though it were still in the planning stages and they could still decide not to go through with it.

Basically this entire chapter seems to exist for the purposes of telling people who want to visit our nation’s capital that they really do not want to drive there, but Anne Marie gets them through the urban maze unscathed. The stolen car with MD plates having been abandoned, John and Andy still have to scope out the Watergate complex, while May and Anne Marie (who get along great from the start) go shopping and sight-seeing, but in fact they do a better job casing the joint as well–join a group of prospective renters touring the apartment complex, find out everything the guys needed to know.

And turns out the joint is empty when they break in (this isn’t a residence, just a place to crash when Max is in lobbyist mode, so no valuable art to steal). They set up camp there and wait. Dortmunder is disgusted. Andy is somewhat more enthused, because there’s fifty thousand dollars in bribes, I mean PAC money, waiting there for a Fairbanks aide to take it to various recipients, as they learn from the answering machine message the underling left, referring to the ‘PAC Packs.” Possibly to be put in a Fed-Ex PAK. Dortmunder is irritated by all the variant spellings of ‘pack’ (as his creator would have been). Andy is just delighted to see this unexpected dividend. And horrified when John doesn’t want to take it.

See, Dortmunder figures Fairbanks has to show up at some point, but this employee is going to show up for the cash, and if he doesn’t find it, he might call the cops, and he’ll certainly call Fairbanks. John is adamant–if it screws up his getting the ring back, they can forget about the Fifty G’s.

Kelp’s agile mind searches feverishly for a work-around, and he says they’ll leave a note saying Fairbanks’ secretary took it for distribution. Dortmunder grudgingly agrees, and they leave with the money, figuring they’ll come back later for Fairbanks and the ring.

(Anne Marie is doubled over with laughter when she hears about this–“At last,” she said, when she could say anything again, “the trickle-down theory begins to work.” )

But before they can go back to the apartment to try again for the ring, Wally Knurr calls, saying that Fairbanks won’t be staying at the Watergate apartment after all, and that his location will no longer be made known to his corporate empire at large–so Wally won’t be able to track him via the internet anymore. What gives here? Well, Mr. Fairbanks, staying at his beachfront condo in Hilton Head, has been consulting The Book, as he calls it. And the ancient wisdom of the Orient is urging caution.

Thunder in the middle of the lake:

The image of FOLLOWING.

Thus the superior man at nightfall

Goes indoors for rest and recreationHmmm. The Book often spoke of the superior man, and Max naturally assumed it was always referring to himself. When it said the superior man takes heed, Max would take heed. When it said the superior man moves forward boldly, Max would move forward boldly. But now the superior man goes indoors? At nightfall? It was nightfall, and he was indoors.

(At this moment in time, unbeknownst to Max, Dortmunder was breaking into his apartment at the Watergate for rest and remuneration, which for him amounts to the same thing.)

He probes further into the text, which is suggesting that someone is following him. Could it be the annoying Detective Klematsky, who suspects him of burgling his own residences for the insurance? He needs more information, so he does another coin toss, this one leading to a hexagram–The Marrying Maiden. Max doesn’t like that one. He strives for the proper interpretation, and suddenly it comes to him–the ring! That burglar is coming for his ring!

And Max is as perversely determined to keep the ring as Dortmunder is to regain it. So this is why he never came to the Watergate apartment as planned, and this is why he’s made his movements a secret, even to most of his employees. But there’s one trip he can’t conceal–he needs to go to his casino in Las Vegas. And it occurs to him that this thief will make a try for the ring there–so he can set a trap. He shall yet prove he, Max Fairbanks, is the superior man, not this bilious brigand!

So Max heads for Vegas, making the needed arrangements with his security staff to nab Dortmunder in the act of lèse-majesté. While Dortmunder begins to put together a string for what will prove to be his biggest and best heist ever.

In the meantime, Andy Kelp has one of his little tete-a-tetes with his friend Detective Klematsky at a New York restaurant, a New Orleans themed eatery this time. And weirdly, this time Klematsky is buying. Because he’s the one that needs information. He wants to know if his old friend Kelp has heard about any people in his profession doing fake burglaries as part of an insurance fraud scam.

He knows that Andy’s eyes blink rapidly when he tells a lie. What he doesn’t know is that Andy can do that on purpose too. So Andy tells him he never heard about anything like that, his eyes blinking furiously all the while. Telling Klematsky exactly what he wants to hear, while pretending to do nothing of the sort. Like Alan Grofield (the Stark version of that character), Andy Kelp can even lie with the truth. And confirmed in his suspicions, Bernard Klematsky, who finds insurance fraud particularly offensive, is now determined to arrest Max Fairbanks for one of the very few white collar crimes Max Fairbanks is not guilty of.

And as Dortmunder enters the O.J. Bar and Grill, we get another scintillating discussion relating to issues of the day, while Rollo the bartender attempts to put up a new neon beer sign.

“It’s a code,” the first regular was saying. “It’s a code and only the cash registers can read it.”

“Why is it in code?” the second regular asked him. “The Code War’s over.”

A third regular now hove about and steamed into the conversation, saying “What? The Code War? It’s not the Code War, where ya been? It’s the Cold War.”

The second regular was serene with certainty. “Code,” he said, “It was the Code War because they used all those codes to keep the secrets from each other.” With a little pitying chuckle, he said “Cold War. Why would anybody call a war cold?”

The third regular, just as certain but less serene, said, “Anybody’s been awake the last hundred years knows, it was the Cold War because it’s always winter in Russia.”

The second regular chuckled again, an irritating sound. “Then how come,” he said, “they eat salad?”

The third regular, derailed, frowned at the second regular and said, “Salad?”

“With Russian dressing.”

After a while, they start arguing about what the code is called–zip?–civic?–Morse? Rollo the bartender tries telling them it’s called a bar code, and is accused of having a one-track mind. And you have seen far weirder and more uninformed conversations than this happening online, probably participated in a few, and there wasn’t any beer being served during them. Think you’re so smart. Hmph.

Dortmunder is not kidding around with this job. He’s calling in the heavy artillery. If you know of anything heavier, all I can say is, I surrender. This cannon already settled the argument up front by demonstrating a cold cure that involves squeezing all the bad air out of a person.

Kelp continued to hold the door open, and in came a medium range intercontinental ballistic missile with legs. Also arms, about the shape of fire hydrants, but longer, and a head, about the shape of a fire hydrant. This creature, in a voice that sounded as thought it had started from the center of the earth several centuries ago and just now got here, said, “Hello, Dortmunder.”

“Hello, Tiny,” Dortmunder said. “What did you do to Rollo’s customers?”

“They’ll be all right,” Tiny said, coming around the table to take Kelp’s place. “Soon as they catch their breath.”

“Where did you toss it?” Dortmunder asked.

Tiny, whose full name was Tiny Bulcher and whose strength was as the strength of ten even though his heart in fact was anything but pure, settled himself in Kelp’s former chair and laughed and whomped Dortmunder on the shoulder. Having expected it, Dortmunder had already braced himself against the table, so it wasn’t too bad.” “Dortmunder,” Tiny said, “you make me laugh.”

“I’m glad,” Dortmunder said.

Tiny is even more amused to hear Dortmunder’s plan–to rob an entire casino. Knowing in advance that Fairbanks will be setting a trap for all of them. Vegas is a hard target at the best of times. But casinos are one of the few places left in this modern electronic world that have a whole lot of untraceable cash on hand. And in the midst of yukking it up over Dortmunder’s recent professional embarrassment, he’s been hearing about all these amazing scores that follows it. He’s listening.

So are Stan Murch and Ralph Winslow–the latter a lockman who is known for always having a glass full of liquor and ice cubes in one hand. A string of five is usually as big as Dortmunder wants to get–he likes to say that if a job can’t be pulled with five guys, it’s not worth pulling. But this is no ordinary job, and will require no ordinary string. And it will require a plan. Which falls on him.

“You must have an idea,” Andy Kelp had said at one point, for instance, but that was the whole problem. Of course he had an idea. He had a whole lot of ideas, but a whole lot of ideas isn’t a plan. A plan is a bunch of details that mesh with one another, so you go from this step to this step like crossing a stream on a lot of little boulders sticking out and never fall in. Ideas without a plan is usually just enough boulders to get you into the deep part of the stream, and no way to get back.

Westlake had Kelp say something like this in Drowned Hopes, and clearly he’s talking about more than heists here. A novel, you might say, is a bunch of details that mesh with one another, right? Westlake liked to write from what he called the ‘push’ method of narrative storytelling, where he would start with some basic ideas, and then push forward into the story, working things out as he went, listening to the characters, minding the terrain. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t. Fact is, a plan worked out perfectly in advance of a job is one of those things God loves to laugh at (along with Dortmunder).

He can’t work it all out without going there and seeing the lay of the land. Knowing who he’s working with, what tools he has in the kit. And the string keeps growing by leaps and bounds, as more and more old associates, many of whom have not been seen in some time, volunteer for this Vegas casino heist. You might say they’re an all-star cast. Or you could come up with some ruder term. Something rodentine, perhaps?

Let’s lay it out. Planner: John Dortmunder. Drivers: Stan Murch and Fred Lartz (and his wife Thelma, who does all the actual driving in the Lartz family these days). Lockmen: Ralph Winslow, Wally Whistler, and Herman X (who is now just Herman Jones, after doing a stint as Herman Makanene Stulu’mbnick in Africa, and being a Jones must make life much simpler for a thief, all things considered). Utility infielders: Andy Kelp, Tiny Bulcher, Gus Brock, Ralph Demrovsky, and the frequently unfortunate Jim O’Hara (but not this time, baby).

That’s either twelve or thirteen (depending on whether you count Anne Marie, along for the ride, much to Andy’s consternation), and we’ve seen Westlake put on this kind of passion play before, in The Score, and Butcher’s Moon–one more indication that a long-buried alter-ego is stirring within him–but there’s also seven unnamed associates in the string, for a grand total of twenty. Even Parker never had a string that big. Or a target this well-guarded.

Most of them come down from New York with Andy and Tiny, in a purloined mobile home, an Invidia, and of course Westlake made that name up, along with a bunch of other fictional mobile homes they considered at a dealership in New Jersey, before deciding this was the one they wanted to steal. There were Dobermans guarding the dealership, but they got some nice raw hamburger with happy pills inside, and went happily to sleep, dreaming of rabbits. Cute.

But all this time, Dortmunder has been checking out the scene in Vegas (with Kelp, who then heads back to New York to round up some needed items, as mentioned). And everybody who sees Dortmunder figures he’s up to something, which of course he is, and they’re all telling him forget about it. Vegas is a burial ground for guys with big plans. He keeps insisting he’s just a tourist, here to see the sights, try his luck. “Uh-huh” they keep saying–the waitresses, the motel clerk, everybody. He just does not look like the sight-seeing type, and the only gambling establishment he’d fit in at would be a racetrack.

The security men spotted him as a ringer almost immediately when he showed up at the casino, but Kelp got him some new clothes. Which are very definitely going to stay in Vegas when he goes.

The pants, to begin with, weren’t pants, they were shorts. Shorts. Who over the age of six wears shorts? What person, that is, of Dortmunder’s dignity, over the age of six wears shorts? Big baggy tan shorts with pleats. Shorts with pleats so that he looked like he was wearing brown paper bags from the supermarket above his knees, with his own sensible black socks below the knees, but the socks and their accompanying feet were then stuck into sandals. Sandals? Dark brown sandals? Big clumpy sandals with his own black socks, plus those knees, plus those shorts? Is this a way to dress?

And let’s not forget the shirt. Not that it was likely anybody could ever forget this shirt, which looked as thought it had been manufactured at midnight during a power outage. No two pieces of the shirt were the same color. The left short sleeve was plum, the right was lime. The back was dark blue. The left front panel was chartreuse, the right was cerise, and the pocket directly over his heart was white. And the whole shirt was huge, baggy and draping and falling around his body, and worn outside the despicable shorts.

Dortmunder lifted his gaze from his reproachful knees, and contemplated, without love, the clothing Andy Kelp had forced him into. He said “Who wears this stuff?”

“Americans,” Kelp told him.

“Don’t they have mirrors in America?”

And it works. The same security guys who started tailing him the moment he showed his face don’t give him a second look in this get-up. Just another rube contributing to their payroll (as opposed to stealing it). The motel clerk, who has seen them all come and go, just says “Uh-huh.” She may be impressed, but she’d never admit it.

Dortmunder’s plan is starting to come together in his head now. He’s made contact with a former New Yorker, a former heist-man running a perfectly legitimate shady business operation manufacturing cheap knock-offs of famous brands of this or that, fellow named Lester Vogel. He’s quite happy to provide needed materials for the job. Just delighted to hear a New York accent again, accompanied by New York rudeness. A bit confused as to why Dortmunder is expressing interest in tanks of various gases he has on the premises.

And staying at the hotel that goes with the casino, Anne Marie Carpinaw is wondering what the hell she’s doing here, and so is Andy, and yet they do seem to enjoy each other’s company, and quite a lot of sex seems to be going on, though this being a Dortmunder novel, it is only vaguely alluded to in passing. At one point, in her room, she says she’s not sure they belong together, but then he asks her if this is a good time to bring that up, and she says “Well, maybe not.” Not such an unusual conversation for a new couple to have.

She is, however, going to some pains to make sure she doesn’t get rounded up with the rest of the gang if the heist goes sour. She watches a lot of Court TV. Actually appearing on it doesn’t appeal to her.

So all the players have been assembled in one place–even Detective Bernard Klematsky is on his way to Vegas. And little hearkening to any of these impending events, other than his imminent capture and final defeat of that pilfering plebe who should learn to know his place, Max Fairbanks waits at a guest cottage on the casino grounds, his security men instructed to not stay too close to him, so as not to scare Dortmunder away. They are not happy about this, but he’s the boss.

He’s also got to deal with the manager of the Gaiety Hotel, Battle Lake, and Casino, Brandon Camberbridge, a happily closeted gay man, with a wife who happily cheats on him with various non-gay men, a dowdy older secretary who happily serves as a surrogate mother, and he loves his job as much as anyone has ever loved any job in the history of work. And in the course of his conversations with Brandon, Max realizes that this guy actually thinks of Max’s casino as being his casino, and makes a mental note to transfer him elsewhere. Doesn’t pay to let his employees ever forget they are just employees. Only one person actually matters, and that is Max Fairbanks.

Um, yes–the Battle Lake. Las Vegas was, by this time, getting to be more and more about putting on a show for the tourists, and less and less about honest gambling. A theme park with slot machines. The Battle Lake is an artificially created body of water upon which remote controlled full-sized replicas of various warships do ersatz battle with each other, for the edification of the masses. It sounds a bit more Disney than Vegas, but I guess that’s the point–that and the fact that the Tui symbol on that ring Max is defending, and Dortmunder is seeking, means Joyous Lake, and Max’s recent I-Ching readings have been referring obliquely to a lake, and intimating that less than joyous developments are in the offing.

He tries once more to divine his future through the coin toss, and the passages they lead him to, and here’s the thing–it’s pretty clear that in this story, the I-Ching really does work. But convinced as he is that he is a Man of Destiny, Max is doomed to keep projecting what he wants to see onto the auguries of The Book. “When one has something to say, it is not believed.” (And would you believe that every single I-Ching quote in this novel is 100% real?)

He comes very quietly, oppressed, in a golden carriage.

Humiliation, but the end is reached.Well, wait now. Who comes very quietly in a golden carriage? The plane that had brought Max here, he supposed that could possibly be thought of as a golden carriage. But had he been oppressed?

Well, yes, actually he had been, in that he was still oppressed by the thought of the burglar out there, prowling after him. So that’s what it must mean.

It couldn’t very well be the burglar in a golden carriage, could it? What would a burglar be doing in a golden carriage?

Again, Max went to the further commentaries in the back part of The Book, where he read,

“He comes very quietly,”: his will is directed downward. Though the place is not appropriate, he nevertheless has companions.

I have companions. I have Earl Rayburn, and Wylie Branch and all those bulky security men. I have the hotel staff. I have thousands and thousands of employees at my beck and call. The place is not appropriate because a person in my position shouldn’t have to stoop to deal personally with such a gnat as this, that’s all it means.

And that’s why there’s humiliation in it, the humiliation of having to deal with this gnat myself. But the end is reached. That’s the point.

Come on, Mr. Burglar. My companions and I are waiting for you, in our golden carriage. The end is about to be reached. And who do you have, to accompany you?

Oh, he really should not have asked that question. And the Invidia has actually been painted silver, but that’s such a niggling little detail.

Stan Murch, Jim O’Hara, Gus Brock, and the one and only Tiny Bulcher start off the caper. Stan and Jim pose as deliverymen bringing more oxygen tanks for the casino to ‘enrich’ the air inside the casino, encouraging people to stay up later,and lose more money. The tanks are green, from Lester Vogel’s establishment, but what’s inside them is nitrous oxide–laughing gas.

And with a bit of not-too-gentle prodding from Stan, Jim, Gus, and most of all Tiny, the guards prove quite willing to show them just where those tanks need to go. This is an upsetting and painful experience for the guards, as it would be for anyone, but they start to relax shortly afterwards. These are considerate robbers, who bring their own anesthetic.

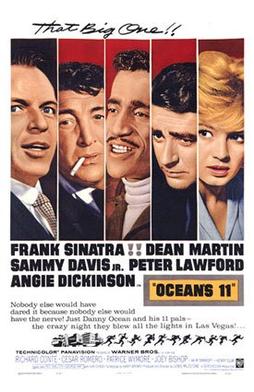

There’s some nice scenes with Herman, posing as one of Max’s employees from Housekeeping, marching right into Max’s guest cottage on the pretense of needing to clean up, Uncle-Tomming his way around Max and the guards–unable to grasp that Dortmunder might have a black associate, or any associate–laughing at them on the inside. (And wouldn’t Sammy have been just perfect to play Herman, back in the day? This is Vegas, I hardly need say which Sammy I mean.)

Herman is done playing around with politics, foreign or domestic. He’s just a straight heister now (well, presumably still bisexual, you know what I meant). He’s going to let his profession know he’s back, black, and better than ever. And I still think Westlake should have given him his own novel, but a bit late now.

So they do the heist. That’s not really important to Dortmunder. Much as these guys may be his friends, they’re still professionals, independents. Nobody’s errand boys. He needed to give them a reason to stick their necks out this far, and money usually works. He’s not leading them–he gave them a plan, and they ran with it. And now the rest is up to him. He wants that ring.

He waits until the string is ready to leave with the loot (two million–more than Parker ever got until Nobody Runs Forever), then he calls the cops, and reports a robbery. And all holy hell breaks loose.

Klematsky picks this moment to try and arrest Fairbanks–he assumes this casino heist is just another insurance scam–Max’s local security man is disgustedly assuming the same thing–explains Max’s odd behavior–he was working with the heisters.

Max, unable to process that he, not Dortmunder, is being arrested, lams it out onto the grounds, as the Battle Lake catches fire, and bits of burning artificial shrubbery are flying everywhere. All he can think now is that he needs lawyers, lots and lots of lawyers. But first he needs someone to get him out of this inferno. A helpful fireman in a smoke mask offers his services. Guess who.

“Give me that ring!”

“No!” You’ve ruined everything, you’ve destroyed–”

“Give me the ring!”

“Never!”

Max, inflamed by the injustice of it all, leaped on the false fireman and drove him to the blacktop. They rolled together there, the false fireman trying to get the ring, Max trying to rip that mask off so he could bite the fellow’s face, and Max wound up on top.

Straddling him. Winning, on top, as he always was, as he always would be. Because I am Max Fairbanks, and I will not be beaten, not be beaten.

You didn’t expect this, did you, Mr. Burglar? You didn’t expect me to be on top, did you, holding you down with my knees, ready now to give you what you deserve, kill you with my bare hands, rip this mask–

And at this point, wouldn’t you know, up runs the normally mild-mannered Brandon Camberbridge, in the grip of a berserker rage. He must have heard about how Fairbanks set up the robbery. His beautiful hotel. Ruined. Pillaged. Ravished. He beats the bullshit out of Max, as so many other of his employees must have yearned to do across the years. And as Max lies there, defeated, barely conscious, Dortmunder, back on his feet, calmly reaches down, takes his ring right off Max’s finger. And that’s game.

As the book concludes, we learn that the insurance fraud charges didn’t stick (because they weren’t true), but in the process of being closely investigated, all this other stuff Max had gotten up to started coming to light. His business, like his life, not to mention his character, could not hold up to close scrutiny. Hey, I didn’t say anything, it’s just a fun crime novel.

So what was it all about? How was this about identity? Sure, we got Anne Marie Carpinaw’s crisis, going from unhappy wife to oddly entertained heister’s moll, and she and Andy will, against all odds, somehow stay together the rest of the series, and I don’t really care.

And we got Andy Kelp himself finding a new side to his identity; more stable, effective, reliable, amorous–but still crookeder than Lombard Street in San Francisco. And we got Herman X/Jones, back from Africa, recommitting to life on the bend, having found that thieves are often more trustworthy than politicians in a developing nation (or any nation). And we got the confused identity of Brandon Camberbridge, the lackey who thinks he’s the boss, to amuse us, and serve as a convenient plot device for the climax.

And this is all entertaining enough, adds to the general fabric of the story, but none of it really matters. This was about John Dortmunder vs. Max Fairbanks. Who was the ‘Superior Man’ referred to in the I-Ching? Who is the Superior Being in any clash of personalities? If you’re Donald Westlake, you’d say it’s the one who knows himself. (Or herself.)

Dortmunder could never, ever, if he lived to be a hundred, think of himself as superior to anyone. The word isn’t even in his vocabulary. He’s been a sad sack and a loser all his life, born under an unlucky star, cursed to be Fortune’s Fool, and he doesn’t kid himself about that. But he knows who he is, and he knows what he’s capable of. Never overestimating himself, he can rise to the occasion when destiny calls. However, he doesn’t waste his time trying to know the future. Not his department.

He tells May he’s not superstitious (while she rolls her eyes a little and says nothing), but he thinks now that ring isn’t lucky after all–he’s not going to wear it again. All its luck must have been used up by her uncle, and now it’s a jinx–losing it meant good luck for him, bad for Max Fairbanks. That’s his explanation for what happened, for how one of the unluckiest guys alive turned the tables on Scrooge McDuck crossed with Gladstone Gander (the Beagle Boys always go to jail in the comic books).

But really, it was more about Max. Max may have started out knowing himself, after a fashion–knowing he was a scoundrel and a liar, knowing that nobody mattered to him but him. And that’s fine, I suppose, in its place–as long as you don’t start taking yourself too seriously. If there’s anything more deadly to an honest unflinching sense of self than being filthy goddam rich, it’s delusions of grandeur–and the two so often go together, you ever notice that?

The oppressed of the world (some of us vastly more oppressed than others) can’t afford delusions of grandeur. We’re too busy trying to survive. And now and again we do come across a Max Fairbanks. And now and again, we do manage, against all odds, to give him one in the eye.

But most of us don’t know ourselves as well as John Dortmunder, it must be said. The Max Fairbanks’s of the world and their delusions can be damnably persuasive. They play on our vanities, as we tickle theirs. So sure, why not take a preening narcissist, an ego in search of a human being, a megalomaniac who can never have enough power, a seething mass of resentment, misogyny, racism, petty tyranny, and rage, and make him the most powerful man on earth? With nuclear weapons to boot. What’s the worst that could happen?

The thing about Dortmunder is, he’s not a killer. But the ‘hero’ of our next book learns, to his amazement, horror, and disturbed satisfaction, that he’s a damned efficient killer. And he can’t afford to indulge his newfound gift on personal vendettas. He’s got to use it for job-hunting. And I’ll have to write a little intro to this one, before I get to reviewing it. And I’ll do that. After I bury my father. Not a metaphor.

Hey, the Ax falls on all of us, sooner or later. That is a metaphor. I hope.

First things first: I’m sorry for your loss. I lost my father last year, and even when you know it’s coming, it’s a blow.

Thanks for the write-up. The Score and (especially) Butcher’s Moon seem the obvious touchstones. BM (huh, maybe don’t abbreviate it) sees its thief protagonist not caring so much about the heists, but using them as a carrot to get his fellow heisters to participate in his revenge plot. I wouldn’t have been surprised if Dortmunder had taken a 23-year hiatus after this one. But that would take us to 2019, and the ax fell long before that.

And yes, it’s very much about identity. Not mentioned in Part 1 is the brief opening chapter with A.K.A., in which Dortmunder is asked to assume another identity (another Fred, in fact). That little caper falls through before it can even get started, but something must have stuck, because Dortmunder spends the rest of the novel behaving like someone else (a non-violent Parker, if that’s not too much of an oxymoron). “Come back when it’s sunny,” Max (the other Max) suggests, after after Dortmunder’s uncharacteristically successful negotiation over the price of the stolen car. “Rain brings out something in you.”

It’s not the rain. It’s the revenge.

Safe travels to you.

I saw the Ax falling; it just fell a bit faster than I thought it would. But we’d said all we needed to say to each other, made our peace. So all that’s left, really, is bafflement. Now I can no longer say “Mr Fitch? That’s my dad.” Mr. Fitch is me. Talk about an identity crisis.

The difference with Butcher’s Moon is that part of what Parker needs to reestablish equilibrium is money, but to Dortmunder it’s really all about the precioussss. He gets so much money this time precisely because he doesn’t care about getting any money. And once he’s got the ring, he doesn’t want that anymore. He’ll put the ring in a drawer, he’ll blow most of the money at the track, and all that will be left–will be him.

I could have made this another three or four parter, and somehow I didn’t want to, much as I like it. I left out the bits with AKA, for the sake of cutting to the chase, and seeing your apt analysis of that chapter where John works so hard to pretend to be somebody else, I think that was a mistake, but then again, why should I do all the work?

I already used this Yeats poem (his last) to introduce the Nephews, but it bears repeating. This passage I can type with my eyes closed. Probably with the wrong punctuation, but—

Only Dortmunder already chose his mate, so maybe that part of it skipped over to Kelp. He and Dortmunder have become a sort of group intellect by now. What one lacks, the other provides.

And thank you, Greg, for not maintaining a respectful silence in light of my bereavement. It’s the very last thing I want right now. I won’t be doing much real writing the next few days, but conversation–that I could use.

Very sorry to hear about your father. I lost mine almost 20 years go, and still it’s a hard thing. It’s why the end of Field of Dreams makes even very tough men cry, and why Inigo finally has to drop his mockery and let the pain through:

Offer me money.

Yes!

Power, too, promise me that.

All that I have and more. Please.

Offer me anything I ask for.

Anything you want.

I want my father back, you son of a bitch.

Yeah, but that’s a fantasy–that you have somebody to take revenge on, and revenge makes you feel any better about not getting to see your father again. Not sure that works even for Spaniards. But it works beautifully to express the emotion. Very hard to fight a staph infection with a rapier. None of the doctors mentioned that as a potential treatment.

I thought about bringing this up in the review, but I wanted to keep things neat. Here’s the thing–once he started successfully romancing a beautiful abandoned woman, I found it hard not to start reimagining Kelp a bit. He’s never a big guy in my mind, he’s got to have a narrow nose, he’s got to have a cheerful sunny outlook, combined with a certain shiftiness–but honestly shifty. Like it’s just normal for him, there’s no malevolence in it. You can’t dislike him for being a crook, any more than you’d dislike a squirrel for robbing a bird feeder (okay, some people with bird feeders say they hate those pesky heister-squirrels, but I think they secretly enjoy the challenge of trying to fend them off).

Anyway, Kelp can’t be a hunk, but he’s got to have some kind of cuteness factor going on, or he wouldn’t have gotten anywhere. So, for what it’s worth, if they ever do that TV series they were reportedly talking about doing–

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Feuerstein

After playing the best doctor on the planet all those years, you think he might enjoy playing a guy who steals from doctors? 😉

Most of the actors who played in the various Dortmunder-derived movies left no mark, but I do sometimes think that after George Segal, Kelp began looking and sounding a bit like him in the books. That really was an inspired moment of casting. The later developments, the nose, the avidity for novelty, the unexpected charm with the ladies, they all seem Segalian to me. Of course he aged out of the character very soon after playing him.

Other than Lee Marvin as ‘Parker’, that’s my favorite bit of casting in all of the many Westlake adaptations over the decades. Pity the script they filmed (a very far cry from the script Goldman turned in) got Kelp even more wrong than Dortmunder. Of course, if that weren’t the case, Segal might have totally stolen the show, which could have been a problem.

I agree sometimes Westlake was impacted in later books by a particular film adaptation, but he usually resisted that–it would crop up in small subtle ways. Andy’s love life basically wasn’t referred to until this book, though we’re told he’s been quite active prior to meeting Anne Marie. It just wasn’t relevant to the books before this one, and even though she stuck around, it wasn’t that relevant to what came after, either. Sex is not what’s being sold here.

The female supporting characters get a lot more time here than in the Parker novels, by and large–but Westlake didn’t really write sex scenes for them and their larcenous lovers. There’s one sex scene in this book, and it’s very short, and so oblique, you have to read it twice to make sure that’s what it is. It’s all much more–domestic–in the Duchy of Dortmunder. May never joins Dortmunder in the shower. Would you want him to? Depends on who plays them in the TV series I increasingly think is not going to happen. Not a peep about that pilot in quite some time.

“‘The Lady’ sucks”

“That’s good news”

One of my favorite snippets of dialogue ever

Where’s it from? Not this book we didn’t discuss nearly as much as I hoped, not that I ever mind talking about The Rockford Files. 🙂

It’s from WTWTCH. Kelp meeting Ann Marie. I don’t have it accessible, but essentially he’s telling the bartender that the lady will have… and Anne Marie objects to the third person description as “the Lady.” Kelp slides his observation in glibly and keeps cheerfully chatting away.

I have it to hand (had to bring it with me to finish the review)–you know, I do believe I missed the double entendre. I was more focused on Anne Marie not liking being called a lady, which I’ve long noticed is a thing for many a good woman. Larry Hart apparently noticed that as well.

He’s getting a bit long in the tooth now, but I’ve always though Greg Kinnear would make a good Kelp.

He’s insufficiently–urban? I think that’s the word. Loved him in Little Miss Sunshine, though. Well, I hated him in the restaurant scene, but that’s just good acting.

I don’t associate him with television–or New York. If they ever do a Dortmunder TV series, they need good TV actors, and some of them better be from New York.

And since the series would only last a few years, we don’t have to worry so much about age. I mean, almost 40 years passed between the first and last novels. The time is clearly passing, since the books are so concerned with documenting (and kvetching about) social and technological changes. Those are so inherent to the story, it does create some problems, if they want to adapt the books faithfully. Just as most of Parker’s heists don’t make sense if people have smartphones and the internet. Though that won’t be true of the last few.

I’d prefer actors with some mileage on them, whoever they are.

I believe I’ve mentioned it before, but I’ve always pictured Ed Norton as Kelp. He’s getting a bit long in the tooth too, but aren’t we all. Mark Ruffalo wouldn’t be bad, but now I’m just cycling through Hulks. (Sorry, Eric Bana. I just don’t see it.)

One thing I like about WTWTCH? is the insight it gives us into Dortmunder’s thought process when it comes to planning. That’s a great little sequence when he keeps going into his little sullen trances, occasionally emerging to ask a pertinent question. Everyone assumes he has a plan but he grumpily denies it. That’s very astute to tie that to Westlake’s writing process. Just keep finding the next stepping stone until you’re all the way across the river.

Yeah, this is one of those books that makes us realize Westlake attacked his novels as if each of them was a heist. He made a very conscious connection between the two, which makes the heist itself the main point of the story, the money a pleasant afterthought. His thieves are artists at what they do, and a good artist is like a thief (though when somebody brings this up with Grofield in Lemons Never Lie, he, being an artist and a thief, would rather talk about something else).

Work is work, right?

Programming too. You solve a problem, then you solve the problem that solution creates, etc. until you’ve got a complete solution, then you realize the whole thing is way too complicated, so you start over solving the first problem a different way etc. etc. and eventually you’re done.

(Or Parker kills you for identifying his location, but we’ll get to that book soon enough).

😉

Of you can use the Lance White method:

Hunches don’t come from any place, Jim, they’re just hunches. That’s how we solve our cases. We get hunches, they turn out to be right, and the case gets solved. Gee, I don’t know how you survive as a private investigator, Jim. You don’t seem to know any of this stuff.

I like the Vern St. Cloud method. Since it involves good acting, and you can be rude to people. Actually, if Lance White is a parody, who are they parodying? Every fictional P.I. I can think of is a rude snarky sumbitch.

Lance is the anti-Rockford: sunny, successful, warm, outgoing, highly principled. Not only would Susan Strasberg not use him and try to dispose of him once he became a liability, she’d hang on his every word when he talked about honesty being the best policy, and turn herself in to make him happy.

“What are you smiling about. Lance? I thought you liked her.”

“I do like her, Jim. I know prison will be tough at first, but if she applies herself to rehabilitation, she’ll emerge a truly fine woman, one any man would be proud to be with.”

“Going to wait for her, are you?”

“She’s lovely, Jim, but not really my type.”

“You mean you two didn’t ….”

“Oh, she tried to convince me, but I could see that it was gratitude, not love. No, Jim, I’m saving myself for the real thing.”

Which Susan Strasberg? Personally, I preferred the Countess. High-maintenance. But so worth it.

My mom was watching Blue Bloods on CBS last night. It seems to have become the Matlock of her generation. And what I want to know is, how is it possible that Tom Selleck gave the best performances of his career before anybody ever heard of him? I mean, on Blue Bloods he just stands there looking all gruff. His Lance White is a nuanced farcical gem of a characterization, but were the Rockford writers so good they could just tailor the character to the actor that perfectly? Because nothing he’s done since has ever come close.

Now that I think on it, Andy Griffith gave his best performances before he was Andy Taylor, but he actually was a great actor. I don’t watch Magnum P.I. and think ‘what a waste of an amazing talent.’

What were we talking about?

Blue Bloods on CBS last night. It seems to have become the Matlock of her generation.

Boy, isn’t that the truth. For a while starting in the 80s, TV provided those reliable comfort-food-for-seniors crime dramas, one at a time, proceeding into permanent rotation on cable channels: Murder, She Wrote, Matlock, and Diagnosis: Murder. And that seemed to be the end of the line. For a while I thought the quirky USA series were their successors, Monk, Psych, etc. But they wasn’t quite the same product. But now we have Blue Bloods, which nobody I know in my “regular” life watches or has even heard of, but it’s the one hour a week my mother makes sure to watch (guided to it by her daughter-in-law). So I really don’t understand how to predict these things.

As for the trajectory Selleck’s acting career, it might look a lot different if he had been free to play Indiana Jones as Spielberg wanted. Some actors are just great within a very particular range (Christopher Reeve is another who comes to mind). I would say Magnum was well tailored to Selleck’s strengths too, but he wasn’t infinitely adaptable.

Here’s the thing–some actors are like those fish that can live in fresh, brackish, and salt water. They can do theater, they can do movies, they can do TV, and they can be great in all three mediums.

But most actors suffocate and die the moment you take them out of their proper habitat.

Harrison Ford would never work on TV. Selleck repeatedly proved he couldn’t make it as a movie star. His best film performance was his least stereotypical (In & Out), but he wasn’t the star there–and again we see his real forte was comedy, but Thespis cursed him with rugged leading man looks, and now he just glowers and grumbles in uniform every Friday night on CBS. He’s a TV actor. Garner could do both, but was much better on TV.

That’s why when we talk about actors for a Dortmunder series, my suggestions tend to be actors known for television. Yes, some film actors work out great on series television, particularly when they get too old to headline films. More rarely does an actor established on television work out as a film star. It’s not a hard and fast rule, either way. And to be sure, cable series have been getting so cinematic that the difference is becoming more academic, and yet–James Gandolfini. A genius beyond compare on the small screen. A very minor player on the big one. It’s a different habitat.

By the bye, does anyone care to offer an opinion regarding the cover art for the Italian edition?

My primary reaction is “What is Chris Christie doing there, and why does he want Dortmunder’s ring?” I guess the question answers itself, doesn’t it? 😉

Dortmunder’s ring has the power to make its wearer invisible to congressional investigations.

The Star-Ledger sees all. 😐

And, to tie everything together, here’s Alan Sepinwall on The James Garner: http://www.hitfix.com/whats-alan-watching/appreciating-the-relaxed-genius-of-the-late-james-garner-maverick-the-rockford-files-much-more

I like your joint concept . . . my thought was more prosaic: “Hmm — I bet Robbie Coltrane would have been a better Max Fairbanks than Danny DeVito. Or is that Ricky Gervais?”

Just a little shout out to recognize Max Fairbanks’ ex-military head of security. Nicely executed supporting character. Mainly in the novel to provide exposition, but not so as you’d notice it because he’s fleshed out just the right amount to be interesting without becoming a distraction.

Which is pretty much always true about the various walk-ons (judges, doctors, secretaries, siblings, and so forth) who populate Westlake’s novels.

A Starkian variation on this same character shows up in Comeback, with a very different boss (not entirely different), and is dealt with much more harshly (because that’s how Stark rolls). You get more background on him, you get into his head more, and you even find out he’s not such a bad guy as former military men go. But he doesn’t know his limitations, and he badly underestimates Parker, and you don’t get to make those mistakes when Stark is at the helm.

Dortmunder novels tend to be more overstuffed with characters–did we really need two heads of security for this one? Makes sense, of course, that there’d be two, the overall head of security and the casino’s head of security–and the consequent turf war, mingled with a certain empathy they share over having to deal with the whims of this petty tyrant–it all works very nicely, tells you something about Max’s organization (and frequent lack thereof). But it necessarily creates some wind resistance in the story itself. And Stark pares all that away, and gets into the guts of the story–and the people. Sometimes literally, but why dwell on the bloody details?

The Comeback guy has another odd quirk, that we should definitely have a discussion about when we get that far.

I think we’re both champing at the bit over Parker’s impending comeback. Still maybe a month before I start reviewing the first of the final eight, since the next book will require much analysis (and I may require much alcohol if our dimension’s version of Max Fairbanks becomes President–sadly, I don’t think our dimension has a John Dortmunder anymore). I haven’t even started re-reading it yet. Been a few years.

But I’ve got a song all picked out to herald its coming. I’ll even give you a hint. 1982. 😉

Harden my Heart?

The title works, but Parker has no tears to swallow. No, this one’s more–cosmic.

Oh, you mean a song for Comeback. I was thinking one for The Ax.

I have a song for The Ax too, but yeah, I was talking about Comeback in this case.

Belated condolences — clearly, I arrived here too late — and a silly question. Does it seem possible to anyone else that Westlake might have been hoping to make this book a fond farewell to Dortmunder? With the mega-caper being old home week for all the people we know in his world, setting up Kelp with another partner besides Dortmunder, and the somewhat enduring payoff too? I certainly don’t presume it’s true — and I enjoy the rest of the saga as much as the next man (yes, even here) — but even the way Dortmunder could be seen as ultimately facing his luck, his fate, makes me wonder.

(By contrast, Max Fairbanks claims to have been facing and pushing his luck all along — but in this book what we mostly see is him stretching that luck past the breaking point, while gradually coming to deny to himself that he’s doing so; he’s come to believe in it too much, it was too big to fail him. But of course it did.)

Good Behavior seemed like an attempt at a finale to the series but Westlake left the door wide open there by letting us know Dortmunder’s probably going to lose all his money at the track, and that surely goes without saying here as well. No matter how much money he gets, he’s going to spend it all, and go back to stealing.

In both cases, there’s a very long interval before he gives us another Dortmunder–five years. Not nearly so long as the gap between Butcher’s Moon and Comeback (Westlake never found it hard to write in the voice he used for the Dortmunders), but perhaps similar in that after doing one of these heister extravaganzas, he needed time to recharge his batteries.

You can see a sort of pattern–a series of very unlucky ventures, capped off by one that succeeds beyond expectations–then back to the usual grind. Good Behavior is followed by Drowned Hopes, where Dortmunder ends up with nothing, in spite of saving a whole community from a watery grave, while nearly ending up in one himself, repeatedly. What’s The Worst That Could Happen? is followed by Bad News–a less severe downswing, they still get a nice payday from the house museum, but it’ll take a long time for those funds to become available via Arnie Albright, and they might as well give up on anything from the tribes.

The only time it really truly seemed like a conclusion–in that you knew Dortmunder & Co. could go back to the same well over and over again–was the last time. We’ll talk about that. Soon enough. Too damn soon.

Amen to that last.

(IIRC, he wrote a time or two — once at least, in the intro to Thieves’ Dozen — that he’d gotten stuck about halfway through the amazing multiplying plans of The Hot Rock. But that could have been a purely plot thing, of course, rather than voice trouble.)

They’re hard books to write, in terms of the plotting. He could hammer out a Parker novel very fast via ‘narrative push’, just let the story take its own course–Parker is all about improvising in the clutch, dealing with unexpected exigencies. But an escalating series of gags requires more structure. Comedy is hard, like I said. I think the final Dortmunders are far less impressive than the final Parkers for this very reason. He tends to ramble a lot, go off on tangents. It’s always enjoyable, but the first three Dortmunders are much more than that. And so are the three epics, which are much longer, and small wonder he had to take long breaks from Dortmunder after each of those.

I came across the following tidbit in a 19-year-old review of Bad News written by the science fiction writer Spider Robinson:

Just a guess, but I’m thinking it may have been to avoid confusion with the contraceptive, which had been approved by the FDA two years prior.

(I tried to blockquote the Robinson quote, but as usual, my tagging skills are sub-par.)

I’ll fix the tagging, and I can’t really fault Robinson, since I often over-analyze Westlake titles myself. Most people don’t know the whole of his work, and he wouldn’t likely have had access to a complete bibliography back then.

There really is no one typical Westlake title, though individual series might, as we all know, get on a particular track for a while. Most of the Dortmunder titles are not questions, word count runs from two to six, and my personal guess is that it had something to do with the unpublished Harlem Detective novel of that same title by Chester Himes (that I still haven’t read, because it would make me sad), that was posthumously released in 1992.

Westlake was a Himes groupie, presumably knew about the novel. So could have been an homage, and then he decided it wasn’t appropriate (titles aren’t copyrighted, but you don’t want two by that title in the same genre if you can help it). Or could be the contraception thing. And honestly, the original title of War and Peace was The Year 1805. Tolstoy changed it later, after several rewrites. Author’s prerogative.

I certainly see no parallel between the plot synopsis of Himes’ book (which makes me sad) and a comic crime novel involving an Indian casino, DNA testing, grifters, grave-robbing, and a house museum heist. But maybe one of these days, when I’m feeling less fragile…..

(You know it’s entirely possible Westlake forgot Himes had already used it, then remembered.)

When Dortmunder pondered if the luck was already starting as he was being pitched the Carrport burglary I immediately went: “What the fuck are you doing, John?! Are you out of your goddamn mind? ”

Sure enough, the deities of comedy repaid that remark with interest.

Anyway, What’s The Worst That Could Happen? is a much better Dortmunder installment, another one that’s high on the list for me.

The main reason lies in the most terrifying sentence put in one of these books: “Dortmunder was very very very angry.”

The hell of it is, I’m only half joking as this is arguably the most successful and competent we’ve seen him so far. You yourself observed that Dortmunder scored more cash here than Parker had at this point in time. And of course, it’s because John isn’t thinking about cash. He’s not even thinking about the ring, not really. It’s the principal of the matter, the humiliation of it all. I love that shit so much.

Anne Marie is…pretty good! Yeah, I liked her, didn’t really have a problem with her, thought her romance with Kelp was cute. She’s not one of the all time greats, but I think she’s a neat addition to the team.

Max Fairbanks, oh boy. What can I say about him that you haven’t already? He’s definitely the best “Rich Asshole Tycoon” character that Dortmunder has faced so far. If only because unlike say, Frank Ritter, Max actually has a final confrontation with Dortmunder and we see his comeuppance on page this time. I also like the idea that Max isn’t even his real name, (you think his backstory was meant to be a subtle Great Gatsby reference?).

The second big highlight of What’s The Worst That Could Happen? (aside from Dortmunder’s downright scary singlemindedness) is seeing more Wally Knurr and Herman Jones action. I like the subtle character development that Wally received since his last appearance. He’s more confident here, less likely to trip over his own words, and he’s more likely to assert his principles than he was in Drowned Hopes. I’m fairly confident he didn’t get together with Myrtle but who knows? My man Herman is, as always, a cuccumber cool cat. And hell, I was pleasantly surprised to see Westlake include a small reference to Herman’s bisexuality. (When he muses about fun sexy times, he mentions how neither Anne nor Kelp are his type.)

Honestly, it’s weird, but I don’t have much to say about this one. It’s a damn great book, I liked it a lot, and I hope it’s not all downhill from here.

Well, you know what James Taylor said about going downhill. Enjoy the ride. And by and large, you always do with these books. Climbing is hard work. 😉

I did not get a Gatsby vibe from Max. You know what vibe I got from him, though the influences are many (because this type has always been with us, and because lawyers). It’s not really possible for him to get hung up on anyone but himself. So no Daisy for Max. Or rather, Max is his own Daisy.

I’ve never really seen much of Fitzgerald in Westlake, though I did all my reading of him very early on, then lost interest. (Same for Papa Hemingway). Since everybody reads him in school, the influence is pervasive, but for the most part pretty vague. Westlake does have a parody version of Papa in Comfort Station, but I can’t say I’ve ever seen a direct reference to Fitzgerald.

Still, I think he’d be more on Fitzgerald’s side in that somewhat misunderstood argument the two had about rich people. Yes, they have more money, Papa, duh (it wasn’t actually him who originally said that). But what does that do to people? Getting it, having it, fighting to keep anyone else from sharing it. How does that change identity? Westlake devoted a lot more time to that question than Fitzgerald ever did. (Fitzgerald was mainly interested in old money, established wealth, and Gatsby was never what he meant by “The very rich are very different from you and me.”

Max wasn’t born rich (unlike his primary model), but once he got there, he took to it. Does the man make the money, or does money unmake the man? Depends on how you make it, I suppose–and what you do with it. Dortmunder, as you say, doesn’t really care about the money, so it can’t corrupt him. It won’t stick with him long either. But that, in the weltanschauung of these books and their author, is all for the best. Get it, spend it, find more. Don’t ever allow what you possess to possess you. As Bernard Shaw once opined, there’s all the difference in the world between rich and prosperous. Prosperous is what you want. In this book, Dortmunder prospers. Max is merely rich, and there’s a dullness to it. Success makes you stupid.

More than any of the others, this book is about luck, but for once Dortmunder’s is good–after being exceptionally bad. As you say, Dortmunder isn’t thinking about anything other than getting his own back, and fortune favors the prepared mind. Which is to say, the professional one. A nemesis is a very good way to focus on the work to be done–did you notice how focused we got coming to the last election? It’s a lot like that. Then, of course, we start to space again. You can only stay in that fugue state so long.

I don’t hate Anne Marie at all, and it kind of makes sense that seeing how happy Dortmunder is with May (without ever admitting he’s happy, because Dortmunder), Kelp would figure at some point he should get something like that, only she’s more of a Claire, wouldn’t you say? And Kelp really liked those Parker novels. She plays a fairly prominent role in one or two later books. But the character never develops much. Well, these books are not in the main about serious character development, anymore than the Jeeves novels are. Once you have the character where you want him/her to be, why mess with success?

Probably the reason he keeps making additions to the gang in this series is that he needs fresh blood to keep him interested, an outsider to stir the pot. I just don’t find the later supporting characters to be on the same level as those of the early books, and I kind of resent the time they take from the ones I love, like J.C. But that isn’t really fair, is it? It’s not their fault. If he had something more to say with those characters, he’d say it. He keeps them on the payroll, and you know they’re still off doing their thing in the background. It’s a bit frustrating knowing that, and not being able to see it. But if he needs any of the old stalwarts, he’ll call them up, as he does Wally and Herman. The problem with J.C. is, she’s a grifter. Her skill set doesn’t really mesh with Dortmunder’s. I think there were ways to solve that problem, but Westlake never got around to finding them. And the bottom of the hill is getting closer and closer. Enjoy the ride. Secret ‘o Life.

We’re entering the era of Dortmunder novels where the supporting cast can actually become too much of a good thing. In that the reader has to slog through what all THEY are doing before getting back to what the core gang members are doing. For me this comes to a head a few books from now (won’t say which one until HG gets there). Luckily that didn’t continue.

I too like Anne Marie just fine. I’d cast Natasha Lyonne to play her*

*Except that Dortmunder just never adapts well to the screen, as the movie version of this book demonstrates. Not that I’ve seen it, I haven’t, but from what I have read not one single person on earth enjoyed it.

I definitely saw Anne Marie as a brunette. And not nearly so flamboyant as Lyonne. I mean, at one point Andy wants Anne Marie to meet Dortmunder (because he thinks she might be useful for the job they want to pull in DC), she thinks he’s talking about a threesome, and she’s very disappointed in him.

I’m not sure that scene works with Lyonne. She might be the one suggesting the threesome.

The way he did supporting characters when he was writing as Stark was, nobody is 100% necessary, and everyone not named Parker is expendable. Parker has colleagues, not friends. (Some of his colleagues turn out to be enemies.) He doesn’t work with the same people all the time, and years might pass before he works with the same string member again. String members can die. Sometimes Parker kills them.

The way he did it as Westlake was, Dortmunder accumulates string members the way a dog accumulates fleas. And that’s pretty much exactly how he sees it. But he just scratches and puts up with it. He may not see them as friends, exactly but he never sees them as enemies. He will never kill them, and neither will anyone else. So they keep accumulating. And he may not work with all of them, all the time, but they keep coming back. By popular demand.

In essence, as I believe I already observed, this is a variation on Butcher’s Moon. In the grip of vendetta (motivated by personal humiliation, rather than the insult of a severed finger), Dortmunder dials in pretty nearly the whole gang. It’s wonderful. But you can’t do that every book. He never really does this again. Because this time Westlake felt like he’d done it right, unlike the previous book, so he could let it go. (Never did it again with Parker either–got it right the first time there).

Parker has no equivalent of the OJ. Parker would think showing up at the same bar, every time you plan a job, is lousy tradecraft, and Parker would be right about that, but the OJ is yet another feature of the franchise people can’t live without. The rules are different because the audience is. This type of story demands a large cast of colorful characters. And the consequence, as you say correctly, is that the stories get less and less focused. But, in fairness, they are also a lot of fun. If you have a place to hang out with people, you need people to hang out with. And who in their right mind thinks anyone who has hung out with John Dortmunder is going to want to stop doing that? The fleas accumulate. Anyway, there’s just one more flea left. I think….?