Hammer: Look, in a little while I’m going to hold an auction sale at Cocoanut Manor, the suburb terrible or beautiful. You must come over. There’s going to be entertainment, sandwiches, and the auction. If you don’t like auctions, we can play contract. Here it is – Cocoanut Manor – 42 hours from Times Square by railroad. 1,600 miles as the crow flies and 1,800 as the horse flies. There you are – Cocoanut Manor, glorifying the American sewer and the Florida sucker. It’s the most exclusive residential district in Florida. Nobody lives there. And the climate – ask me about the climate. I dare you.

Mrs. Potter: Very well – how is the…

Hammer: I’m glad you brought it up. Our motto is Cocoanut Beach, no snow, no ice, and no business.

Scene from The Cocoanuts (1929), and Mike must think I’m nuts for even bothering to mention that. But why a duck? Answer me that, Mr. Schilling. I thought I was the one doing the shilling around here. A fine thing.

“Most people, I believe,” Alice said, “will just go for the baubles, because they won’t want to spend an awful lot of money this late in the season. Just so they take home some little thing. But I will bid on this necklace, and I’ll bid low, and because it’s so valuable it won’t come on the block until very late, when everybody else will already have their little something, and I wouldn’t be surprised if I get it for my opening bid.

“How clever you are, Alice,” Jack said, and patted her shoulder before he went back to his seat and his Wall Street Journal.

She continued to smile at the necklace in the photo. “What a coup,” she said. “To get that necklace cheap, and to wear it on every occasion.” Like all very wealthy women, Alice had strange cold pockets of miserliness. Her eyes shone as she looked across the table at Jack. “It will be an absolute steal,” she said.

“But you don’t care if I live or die,” she said, “do you?”

“I’d rather you were dead,” he said.

She thought about that. “Are you going to kill me?”

“No.”

“Because of the bargaining chip.”

“Yes.”

“You’re a little more truthful than I’m ready for,” she said.

He shrugged.

Let me state for the record that I don’t hate this book at all. I have read it four times, and enjoyed it each time, in spite of all my nitpicking. Hell, if you can’t enjoy a good bit of nitpicking sometimes, you should stop perusing fiction altogether, and were probably born into the wrong reality altogether. This is not a world of Platonic Ideals. I’m far from convinced any such world exists, but this ain’t it, that I know.

But having typed that, I am forced to ponder the unavoidable truth that Parker is, in certain respects, Westlake’s ideal–or rather, Stark’s. Westlake likes things messy, imperfect, the daily scrum of human existence, with all its inherent absurdity–and the potential for love and laughter and self-realization that lies within all that. Stark also aspires to self-realization, but he does so by striking a cold clinical contrast between Parker and the rest of us; never fully knowing ourselves, always caught between what we wish we were, and what we really are.

Why is Parker so quietly and implacably enraged when he’s shortchanged by his colleagues at the start of this book? They’ve promised to pay him back with interest, once the big heist they’re planning is done (having failed to inform him this might happen upfront). Why go to such extraordinary pains to acquire a small fortune through small thefts, simply in order to create a false identity, so he can go to a place he normally would avoid, risk death and (even worse) imprisonment for the chance to erase the insult by killing these men who mean him no harm, taking their ill-gotten gains for himself as restitution? Why not let it go, for God’s sake? It’s just 21k–at the dawn of the 21st century. Claire probably spends more than that per annum on clothes.

Why react this way? Because in Parker’s mind, this is not how it’s done. You pull a heist with some people, you share the proceeds in the manner agreed to upfront, you go your separate ways. No exceptions. He would have had more respect for them if they’d just tried to kill him to get his share, though the response would be no different. Parker doesn’t know from Platonic Ideals, because that’s an intellectual concept, and he’s about instinct. He is, in reality, what someone like Plato can only dream about. Maybe more along the lines of Aristotelian Natural Philosophy than Platonic Ideals, but it’s all Greek to him.

So obviously to me this novel does not properly reflect the Stark Ideal established in my mind by the previous books. It lacks the proper balance of elements. It asks questions of Parker that should never be asked; presents answers to those questions that he would never think to himself, let alone utter aloud. This is why I have such a bad reaction to it. But my response to that is simply to have a good time pointing out all the inconsistencies and false notes in the book, while acknowledging the many fine moments within it. I don’t have to go find Richard Stark and kill him. I mean, even if I could find him, he’d probably end up killing me.

When last we saw Parker, he was lying face down in a swamp in the Florida Everglades, having been shot in the back with a .30-06 rifle, by one of a pair of killers sent to find and eliminate him, so that he can’t divulge the identity of a man whose identity remains a mystery to him. One of those guys who makes murder the answer to everything. One of those pairs of chuckling assassins that used to frequent many a Westlake Nephew book. And in just a few seconds, they’re going to wish they’d stuck with the Nephews.

But this being Part 3 in a Parker novel, we’re not going to find out what happened right away. Chapter 1 is from the perspective of Parker’s three former cohorts, Melander, Carlson, and Ross. They had told Parker to go home and wait for their call, so they’d know he wasn’t after them. Four days later they call. Nobody’s home.

What follows is an irritable debate on the admittedly complex ethical strictures of organized armed robbery. Melander, the mercurial fidgety idea man of the group, feels like they did nothing wrong. Carlson, the pragmatic veteran, says if they’d done the same thing to him as they did to Parker, he’d say they robbed him–they should have considered the consequences of bringing in a fourth man who might have to be shortchanged, before they went ahead and did it. Ross, the peacemaker, says maybe they better just go to Parker’s house in New Jersey and check up on him. And if he’s not there, maybe they can grab his woman and use her as leverage.

Everybody agrees this is a good idea. Until they get to the house and find it deserted. They spend days there, waiting for Parker, Claire, somebody, to show up. All they ever find is places Parker had cached guns to use on anybody who came after him at home. There’s even one behind a sliding panel by the garage door. Each is increasingly aware they are dealing with an ice cold methodical planner, and that there’s a target stitched on each of their backs.

They decide to head back to Florida. It’s really cold in Northwestern New Jersey in winter, even if you’re not right off a lake. They put everything back the way it’s supposed to be at Claire’s house so nobody will know they were there. They get back to their Palm Beach house, and everything is the way it’s supposed to be, so they figure Parker wasn’t there. Not so good at making connections, these guys.

(More fun with nitpicks: Parker is told at the start of the book that the trio needed a fourth man on the Palm Beach job, and if it’s not going to be him, it’ll be somebody else. Guess what? There’s nobody else, they just do the job–a really big complicated risky job–with three men. No explanation of how they were able to rejigger the plan to make that work. Just one mistake among many. Westlake is rarely this sloppy, and never when he’s working as Stark. What was going on when he wrote this book?)

Chapter 2 is Leslie Mackenzie musing on her life, the sequence of events that led her to throw in her lot with Parker. She grew up poor in a place where you’re surrounded by wealth. She got into a bad marriage with a guy who talked big, but talk was all it was. Her mother and sister are an embarrassment and a burden to her, and she’d dearly love to get her hands on a lot of cash, so she can leave them behind, start over.

Sex has never been much fun for her, but she is (of course), starting to become attracted to Parker, wondering what he’d be like in bed. Truthfully, her situation isn’t that desperate. She’s very good at her job, and her job is selling luxury housing to people who can afford it. She just isn’t happy with where and who she is. She’d like to be somebody else, somewhere else. For that she needs a score. And for a score, she needs somebody like Parker. And for this subplot to work out satisfactorily, for Leslie and us, Parker needs to be sexually available to her, at least on a temporary basis, but he’s not. Frustrating.

He is, however, still alive. You won’t believe how that happens. Seriously, you won’t. Chapter 3 is from the perspective of a 23 year old paramilitary grunt named Elvis Clagg. You know that right-wing militia movement that started getting a lot of attention in the 90’s? Seems like some people got started much earlier than that. Warning, racial epithets ahead. Like you couldn’t hear worse at a meeting of the President’s closest advisors these days.

Captain Bob Hardawl himself had founded the CRDF not long after he’d come back to Florida from Nam and had seen that the niggers and kikes were about to take over everywhere from the forces of God, and that the forces of God could use some help from a fella equipped with infantryman training.

Armageddon hadn’t struck yet, thank God, but you just knew that sooner or later it would. You could read all about it on the Internet, you could hear it in the songs of Aryan rock, you could see it in the news all around you, you could read it in all the books and magazines that Captain Bob insisted every member of the CRDF subscribe to and read.

That was an odd thing, too. Reading had always been tough for Elvis Clagg. It had been one of the reasons he’d dropped out of school at the very first opportunity and got that job at the sugar mill that paid shit and immediately gave him a bad cough like an old car. But now that he had stuff he wanted to read, stuff he liked to read, why, turned out, he was a natural at it.

They oughta figure that out in the schools. Quit giving the kids all that Moby-Dick shit and give them The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, and you’re gonna have you some heavy-duty readers.

I’m sure that option is being discussed as we speak, but leaving that aside, Elvis was out on maneuvers in the Everglades, with the rest of the CRDF, and would you believe they just happened to witness Parker being shot? Why, sure you would.

And while there’s no particular reason for them to get involved, the fact is that you get bored marching around in formation with shiny well-oiled automatic weapons all day, and never having anyone to use them on. One excuse is pretty much as good as another. Captain Bob yells something at the thugs. The thug with the .30-06 rifle panics and shoots two of the uniformed thugs armed with Uzis. Problem is, there’s twenty-six of them left, and the guy with the rifle didn’t shoot Captain Bob, who starts barking orders, and the end result is that Parker’s abductors end up getting shot 13 times apiece. Dead and unlucky.

Chapter 4 introduces the 67 year old Alice Prester Young, and her 26 year old husband, Jack. Alice is rich, and Jack is not. That didn’t really need explaining. And I’m not sure this story really needed telling. Westlake wants to satirize Palm Beach society, and that’s a worthy ambition in itself, but how well does it mesh with the story being told? Not very. I strongly suspect this is left-over story material from something Westlake started writing that wasn’t originally going to be by Richard Stark.

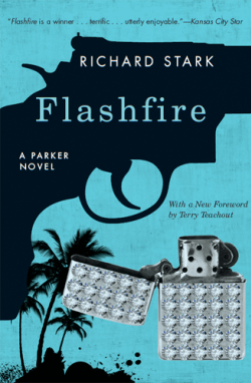

Alice is reading in the paper at breakfast about how a Daniel Parmitt is in the hospital, in critical condition, after being abducted and shot in the Everglades, and she’s asking Jack if they know any such person. Jack doesn’t know, doesn’t care. She goes on from that subject to discussing the upcoming auction of Miriam Hope Clendon’s jewelry, as you can see up top–a certain necklace she’s had her eye on since time immemorial. Jack’s only interest in that stems from his figuring he’ll inherit it someday. We shall be hearing from both of them again, so on to Chapter 5.

Chapter 5 introduces pretty nearly the only non-asshole POV character in the book who isn’t Parker or Leslie; Trooper Sergeant Jake Farley of the Snake River County Sheriff’s department, who is working on the strange case of Daniel Parmitt. He’s irritated on several counts–first of all, those dangerous idiots of the CRDF finally killed somebody, like he always knew they would, but he can’t arrest them, because it was self-defense.

Secondly, he just can’t figure out the angle on this Parmitt. They have the ID papers Parker bought from the late Mr. Norte, which are holding up to scrutiny so far–unlike the more resourceful Leslie, they haven’t thought to run a credit check, because obviously rich oil men from Texas have great credit. Point is, why does somebody like this get waylaid by two men who were self-evidently professional killers? Something’s rotten in the state of Florida (pretty much the default setting there, and not just in crime fiction).

Parmitt was badly shot, and drowned to boot, before the CRDF guys practiced their CPR on him (breaking a few ribs in the process). And yet, miraculously, it looks like he’s going to recover. When Farley questions Parmitt, something about the way the man’s eyes focus on him from his hospital bed makes Farley feel like he’s the one in danger. Unnerving. But no question, the man is still very weak.

Leslie has shown up, wanting to see her friend and client, whom she suggestively suggests may be more than just a friend and client. Leslie quickly figures out Farley, who has a thing for amply proportioned blondes, and is currently married to one, is going to be knocked off balance if she brings sex into the equation, and it works like a charm. He gives her a few minutes alone with Parker, in Chapter 6.

As soon as she tells Parker that the attack on Parmitt made the papers, he knows the man who sent the first two killers will send more, right to the hospital, and there’s no police guard on his room (nor can he request one without making explanations he’s in no position to make). And at any time the cops might take his fingerprints–which will lead back to a dead prison camp guard in the 1960’s, among other things. He tells Leslie she needs to get him out of there, without anyone seeing them leave. She’s taken aback, but tells him she’ll figure something out.

Chapter 7 is set at the site of the auction, the house of Mrs. Helena Stockworth Fritz, who is deeply involved in getting the place ready for the social event that will officially make her the new queen of Palm Beach. Then all of a sudden these two common workmen we recognize as Melander and Ross show up with some amplifiers they say they were tasked with deliverying there. Irritating, but just so they’ll go away, she has them let in, and as promised they stick the equipment where it won’t get in anyone’s way. Until it does.

Chapter 8 is Leslie pressuring her mother and sister into aiding her in springing Parker from the hospital. Her sister Loretta, as mentioned, is mentally disabled, and her mother’s no bright light either. They’re both very nervous about participating in this escape plan. But they buckle when she threatens to move out–her income is all that’s holding them up. And we know she’s planning to move out as soon as she gets her money.

Chapter 9 is the evening of the heist, and switches around a bit, starting with Alice Prester-Young getting her jewels out of the bank, where the Palm Beach elite keep most of their valuables most of the time. They have dressing rooms, mirrors with grey tinting to disguise the marks of time on the faces and bodies of those who look in them. Alice feels she’s earned all of this, even though the entire point of being in Palm Beach society is that you didn’t earn any of it.

Farley is talking about Parmitt with an FBI agent named Mobley, and they agree his story about not remembering anything about how or why he was attacked doesn’t add up, he’s holding something back. Mobley suggests Farley get Parmitt’s fingerprints to him, and he’ll check them for priors. Farley agrees.

Leslie is driving to the hospital with her sister, in a Plymouth Voyager (nice little nod to The Ax there). They pass a fire engine. Guess who’s riding on it?

Then we get a bit more social satire with Mrs. Fritz, learning that even within the 1% there’s a class system, and she sees herself as being at the very top now–too good to even go to the bank to get her jewels and furs with the rest of the hoi polloi, as she thinks of them. She uses the panic room her late husband installed for that. And she doesn’t need any gray-backed mirror. She likes the person looking back at her just fine the way she is. She knows herself better than the others. But she still doesn’t see those amplifiers the grimy workmen delivered, that somehow never got hooked up to the sound system.

Chapter 10 is Leslie and Loretta springing Parker from the hospital by putting him in the wheelchair Loretta was pretending to need. Loretta’s actually having a fun time with the caper now. Leslie is still worried about getting her money, and starting to feel protective towards ‘Daniel’, in spite of herself. But when she asks him what he plans to do tomorrow night, his answer is “Kill some people.”

Chapter 11, surprisingly enough, isn’t about Donald Trump’s financial affairs. It’s another multi-POV chapter, and the only thing of real consequence that happens in it is that the hitman sent to kill Parker in his hospital bed gets there only to find out the bed is empty, and he’s about to be arrested by Deputy Sheriff Farley (showing great presence of mind when he finds the man in Parker’s room, pretending to be a doctor). Farley is delighted to finally have somebody he can question without a lot of doctors making a fuss. Less delighted that Daniel Parmitt has disappeared, but he’ll worry about that later.

Chapter 12 is all Leslie and Parker. He’s recovering from his injuries with astonishing rapidity–not Hugh Jackman with adamantium claws fast, but fast. He’s staying at a condo she’s already sold, that the new occupants won’t be occupying for weeks yet. She’s reached the point where she’s actually trying to talk him out of heisting the heist, but of course nobody can ever talk Parker out of anything. She can’t understand why he’s so much more intent on killing these three guys who never tried to hurt him than he is on dealing with the man who has sent hired killers after him. Yeah, what’s up with that, Parker?

“The other guy’s gonna self-destruct,” he told her, “He has to, he’s too stupid to last. He’s somebody used to power, not brains. But these three are mechanics, we had an understanding, they broke it. They don’t do that.” He shrugged. “It makes sense or it doesn’t.”

Only time I’ve ever felt like arguing with Parker’s logic (not the part about somebody used to power instead of brains; that’s borne out by the headlines we read every morning now).

Actually, only time offhand I can think of Parker arguing for his own logic. Why does he even care what Leslie thinks? The mere fact that he’s making an argument means that he knows it doesn’t make sense, which we know from several past books is something that always irritates him. But in The Seventh, the most noteworthy of those books where he’s knocked off-kilter, he was doing something that didn’t make sense because, in part, a girl he was starting to like had been skewered with a sword by The Amateur.

There was no time to stop and think in that story, everything happened over a very short time frame, which is why that book works so well. And The Amateur had tried to kill Parker, had tried to frame him with the law, had taken all of his money, and was certainly not promising to pay him back later. Given all that, it made perfect sense that Parker’s behavior didn’t make sense, least of all to him.

But in this story he’s had weeks to think about what he’s doing, and now he’s clearly in no shape to take on three armed men, or three unarmed men for that matter. He’s going to do it anyway, because he can’t help himself. This seems less like a wolf in human form acting on instinct than a really hardcore case of OCD. The Sheldon Cooper of Crime.

Chapter 13 is the heist. And a good one, I might add. The gaudy trio use their favored strategy of pyrotechnic distraction–they should probably quit the heisting game, and try putting together a magic act in Vegas. The amplifiers contained incendiary rockets. As anticipated, the rich people forget their innate dignity and stampede like cattle. The trio appear disguised as firemen, in the stolen fire engine–then depart as frogmen, wetsuits under their slickers, over the sea wall into the sea, with the jewels. Next stop, the safe house. Which isn’t going to be as safe as advertised.

Meanwhile, back at the Fritz, the whole soap opera subplot of Alice and Jack concludes with her desperately seeking Jack in the smoke and confusion, afraid he’s been killed–then seeing him carrying the luscious young trophy wife of another elderly rich fool out of harm’s way, and realizing in an instant that he’s just been patiently waiting for Alice to die, and entertaining himself with a woman his own age while he waits. Which Alice probably could have forgiven easily enough, if it wasn’t so blatantly obvious that his first thought when all hell broke loose was to save his lover, not his wife.

He looks back at Alice, the corpus delectable in his arms, and can’t think of a single thing to say. He’s fond of her and all, he enjoys her company, he didn’t mind servicing her sexagenarian sexual needs, wasn’t bothered by the snickering gossip that inevitably surrounds any such marriage, but in a crisis, his true feelings betrayed him–and her. And their whole tidy mutually beneficial arrangement is exposed for the tawdry sham it always was (same goes for his lover, whose husband is now processing the same ugly truth as Alice–money can buy you everything but youth, and youth is worth all the rest of it combined, wasted on the young though it may be).

And that’s a perfectly good short story, for Playboy, maybe, but what the hell’s it doing in a Parker novel? We won’t see any of these people again, and we won’t miss them either. At times, this book feels like a jumble sale of ideas Westlake wanted to do something with, but never found the proper outlet for. On to Part 4, eight chapters, just a bit over fifty pages, and blissfully free of any such distractions. But sadly, not free of some pretty serious problems, and one outright blunder on the part of the author.

Parker has painfully made his way back into Melander & Co’s hideout–last time he was in there, he fixed things so he could get in there without triggering any alarms, or leaving any trace. But last time he didn’t have a bullet wound and several broken ribs, and wasn’t weak as the proverbial kitten. Still, this kitten has claws, and a gun stashed under a Parson’s table. And he’ll have the element of surprise. Or maybe not.

The trio get back from their heist, laughing over how well it went–one of them even saw a dolphin as they swam back to their private beach. They’re improvising too much–it only occurred to Ross at the last possible moment that they needed to sweep the sand behind them, to cover up their footprints. The heat from this heist will be intense, like nothing they ever faced beore. They never did fully process how intense. Rich people don’t like getting robbed (They’re supposed to be the robber barons here! Well, their forebears were, anyway.) In a closed-off place that is entirely controlled by the rich, the cops will be relentless and methodical in tracking down the thieves–or lose their jobs.

But right away they get distracted–by Leslie. Parker curses to himself when he hears it happening. She couldn’t just sit back and wait, she had to come in and look, and they found her. They assume she’s Claire, looking for Parker. Well, they’re half-right. They start interrogating her, slapping her around a little, and then when they lock her in the same room Parker is hiding in, she inadvertently tips them off to his presence. Parker thinks to himself sourly that she’d been better than most amateurs, until it mattered.

Melander isn’t sure whether he wants Parker dead or not. Obviously Parker’s not in great shape, and it’s three against one (he’s not counting ‘Claire’). Parker tells one of his usual lies when he’s faced with guys he wants to kill who are currently in a position to kill him–he was just making sure he’d get his money. They don’t really believe him, but they can sleep on it. And while they sleep, Parker keeps getting a bit stronger, every hour.

The plan, not that it matters now, was that he’d kill them in their sleep. Won’t work now, and far from clear it ever would have worked. But that plan is dead. Parker waits to see what new plan can be salvaged from this mess. And Leslie looks for some way to prove herself to him again.

Next morning, all plans turn to crap. The cops come calling. Melander puts on his faux Texas accent, tries to assure them he’s what he pretends to be, but the fact is, in the harsh light of a major manhunt, his act just doesn’t play anymore. The house is largely unfurnished, in bad shape, there’s a dumpster outside, no contractors at work, and they haven’t even applied for a phone yet.

This isn’t how real rich people live, camped out like squatters in a derelict property–certainly not in Palm Beach. Parker was right all along about this plan being a disaster waiting to happen. The cops, who work in Palm Beach every day, can easily sense Melander doesn’t belong here, that something’s very wrong with this picture. They insist on coming in to look around.

(The absolute worst mistake in this book is something I never noticed before now–see, back in Chapter 1, Part 3, we’re told that when the trio decided to try contacting Parker in New Jersey, they called from the ‘freshly installed phone’ at the mansion in Palm Beach–that very phone the cops now say they never even applied for. That’s not their mistake, it’s Stark’s. Stark doesn’t make mistakes like this. An honest-to-god plothole in a Parker novel. What the hell was going on with the writing of this book? What kind of pressure was Westlake under when he produced it?)

Melander can’t very well tell the law to come back with a search warrant–he does that, they’ll have a cordon around the house in five minutes, the warrant in ten, and SWAT teams in place. He realizes he’s got no choice but to shoot it out–just two of them. He and his buddies can figure out Plan B once the cops are dead.

But Parker’s advance planning comes into play now. He disabled all their guns days ago. Melander pulls the trigger and nothing happens. Except he gets shot to pieces by edgy lawmen, naturally.

Parker and Leslie had been brought downstairs for breakfast. Leslie is sitting at that very table Parker duct-taped his trusty little Sentinel revolver beneath. Parker quietly let Leslie know about the gun, hoping she’d get it to him, but Carlson sees her with the gun in her hand, aims his shotgun at her, and of course that doesn’t work either, but Leslie doesn’t know that (Parker understandably didn’t want to trust her with any further information).

In the ensuing shitstorm, Parker hits Ross with a chair, knocking him into view of the cops, who gun him down with alacrity. Leslie, terrified out of her wits, empties the Sentinel into a confused Carlson. The trio is gaudy in a different way now.

Parker grabs the bags with the jewelry, and goes out the back, signaling Leslie with his eyes that she should say nothing about his ever having been there. He’s still in tremendous pain, and can’t go very far, but he manages to get over the fence surrounding the property, and into a decent enough hiding place, assuming there’s no major search of the area. And then he passes out.

By the time he wakes up, the house is abandoned again. He goes back inside, helps himself to the food and beer his deceased captors stocked the fridge with. Cops come in a few times to poke around, but they aren’t looking for anyone, so he just avoids them in the big rambling house. After a few days of this routine, he’s feeling a lot better–now he just needs to make contact with Leslie one last time.

And here she is–something of a local heroine now. Reminiscent of Claire at the end of The Rare Coin Score, she told the law a good story, used her feminine wiles on her male interrogators, and not only is she not in any trouble, she’s now got the exclusive right to show the house to potential new buyers. So her presence there isn’t going to arouse any suspicion. Parker is pleased with her–she’d never make it long in his business, but in the end, she proved her worth to him. She can live. And she is, of course, due a share of the spoils.

She tells him all the accounts he set up as Parmitt have been frozen. He expected that, isn’t bothered by it. He tells her he’s going soon, will leave the gems in her keeping. She’s amazed he’ll trust her that much, but he reminds her, there is no way she could possibly sell them herself without getting caught. He’ll send a fence to see her, and he figures her end will come to around 400k, give or take. We were told at the start of the book that it would take three fences to unload all this swag, but even I’m getting bored with the nitpicking now.

In the Pre-Claire era, this would be the part of the book where Parker and Leslie hook up. But those days are gone, and Parker feels like he somehow has to explain this to Leslie, why he’s not going to take out his post-heist horniness on her, which she would be more than willing to let him do. For the record, I’m totally fine with the emotions he’s expressing here; not so fine with the fact that he is expressing them. Hey, if this heist thing ever falls through, he could always take a job with Hallmark.

He said, “You don’t want to know about Claire, Leslie.”

“Of course I do,” she said.

He looked at her, and decided to finish that part once and for all. “Claire is the only house I ever want to be in,” he said. “All her doors and windows are open, but only for me.”

A blush climbed Leslie’s cheeks, and she stepped back, looking confused. “You’re probably anxious to see her again,” she said, mumbling, going through the motions. “I’ll see you at eight.”

The plan is she comes to pick him up, drive him to Miami, where Claire is waiting. But plans are always subject to change. Farley shows up at the house, still trying to figure out what the hell happened. He never bought Leslie’s story. He knows Parmitt is tied up in this some way. Parker avoids Farley easily, but waits for him in his car. He’s still got some business left to attend to, and Farley could be useful there.

So Farley comes back to the car, sees Parker, and is taken aback by the man’s sheer gall. They have a little talk, in which Parker admits to no crime, but fills Farley in on why those two hoods tried to kill him in the Everglades. Tells him about this guy, probably from Latin America, probably a general or a drug lord looking for a cushy safe retirement home in the states, tried to cover his tracks by the most stupid brutal means imaginable, because that’s the only way he ever knew to deal with problems–and in so doing, made himself more vulnerable. In so doing, he made Parker his enemy.

The deal is, Parker gives Farley enough information so that he can go to his FBI friend, knowing how to prove the papers Norte gave this man are fake, and in a short time, they can take him down for keeps–a big arrest, very nice for everyone’s careers. If they somehow screw it up, fail to get him, Parker will take the guy out himself. But he doesn’t think that will be necessary. He also teases Farley about his obvious attraction to Leslie. Well, I guess there’s a little matchmaker in everyone.

Farley drops Parker off in Miami. Even gives him a quarter to call Claire with. He would still like to arrest this Parmitt guy, even though he doesn’t exactly have any concrete charges–he could find something if he wanted. The bloodhound in him can smell the wolf in Parker, is feeling the pull to do something about it. Parker reminds him they’re alone. “I’m armed,” Farley says. “So am I,” Parker responds. And flexes his huge hands, which are in easy reach of Farley’s throat. Farley says he’ll always wonder if he could have taken Parker. Parker ends the book by saying “Look on the bright side–this way you have an always.”

Not a bad ending. Not a bad book. Unless you compare it to all the others. Maybe someday we’ll know what happened here, the explanation for all the mistakes and false notes, but I doubt anything will ever explain why Hollywood producers would pick this book to kick off what was supposed to be a long-running franchise, starring a short bald Englishman as Parker (actually named Parker, something Westlake would never have countenanced had he still been around), and a skinny blonde Australian whose name I can never remember as Claire. And Nick Nolte as her dad, who is Parker’s mentor. Seriously. This happened.

But Jennifer Lopez wasn’t a bad pick for Leslie. Even though I know she was only picked because the producers wanted her to do that striptease from Part 1. She looked right for Florida, and she certainly had the curves to play Leslie. But they screwed up that subplot as well. Trying to ‘fix’ the story, they made it ten times worse.

The producers of “Parker” (quotes intentional) were, whether they knew it or not, playing the role of the gaudy trio in this book; so confident of their abilities, so sure they had a perfect score planned, so sure Palm Beach (which they insisted on shooting in, driving up the budget) would be a goldmine for them. And in the end, it didn’t work out any better for them than it did for the movie stars. But it worked out fine for the Westlake estate. So that tracks. Can’t wait for the sequel. I really can’t. Because I’m not going to live that long, and neither is anyone else.

But pretty sure I’ll live long enough to review the next book in our queue, also a Parker, and vastly more satisfactory than this one, in every possible way. Parker is back in his proper habitat–both of them. City and wilderness. And still learning about this brave new world he’s been stuck back into. Adds another string to his bow, you might say.

Anyway, I’ll try to get Part 1 out next week. Anyone needs me before then, I’ll be in the garage, killing a man. Just kidding. I don’t have a garage.

(Part of Friday’s Forgotten Books)

The Alice-Jack storyline (which I quite like) perhaps felt a little less Stark, a little more Westlake, who enjoyed seeing corrupt or craven or morally blank people have their comfortable worlds come undone as inadvertent fallout of one of Dortmunder’s schemes. That said, the story didn’t necessarily feel out of place to me here. Extraneous civilians caught in the fallout are a part of Parker’s world. Poor Eddie Wheeler with his head cold, who should have spent the night with Betty. And I wonder about Susan Cahill, whether she got scapegoated by her bosses and had to find yet another career. Carving out a comfortable little niche for yourself is asking for trouble when Stark (or Westlake) is your god.

But the doors and windows quote about Claire, that never should have made it to the final draft. If Stark couldn’t part with it himself, he should have had an editor brutal enough to take that sentence out with a damned machete.

It seems clear that the trio’s plan would have failed spectacularly even without Parker’s interference. So I guess that’s why Parker felt he couldn’t wait. He knew these guys were going down, and wanted to be there to do it himself before they hit the ground on their own. Still, it’s an expensive compulsion.

I know, the same thing occurred to me, that we’ve seen this before–but Eddie Wheeler actually meets Parker. Parker talks to him, ties him up, leaves him in an alley–and you know what he does to Susan Cahill. Parker never knows Alice and Jack exist, not that he’d care. They don’t even interact with the trio. Mrs. Fritz just barely meets two of them. I mean, there are innumerable people impacted by a major crime, but this isn’t an Arthur Hailey novel, dammit. You don’t just bring in people for the sake of bringing them in, padding out the cast. There has to be a valid connection made. These are minimalist books, not “A cast of thousands! An epic tableau!”

If Parker had never come to Palm Beach, the same exact thing would have happened with Alice and Jack. It’s not hooked up properly into the larger story–and that’s true of a lot of the different pieces of this novel–they don’t fit together into a coherent whole. Certainly not the way they do in The Score, which is about as seamless as they come. I absolutely agree, it’s the same general type of subplot Stark did in previous books, but it’s not done the right way.

And thing is, he can’t identify with these people at all, you know that. Westlake’s contempt for the very wealthy is one of the major constants of his writing (and his identity), and I am more than sympathetic, but it can make it hard for him to write from their perspective, unless he’s in full satiric mode, as in Good Behavior and other books. Here, he’s trapped between sympathy and disgust. He needed to work more on getting the balance right.

I didn’t mind the doors and windows quote when I first read it, but when I first read it, I’d only just made Parker’s acquaintance–the more I came to know him, the worse it sounded. I have used that quote with people I’ve argued with, who say Parker doesn’t give a damn about Claire, she’s just a useful sexual appliance for him, and he’d walk away from her the moment she became a problem–misogynists, projecting their own shallow wants and frustrations into Parker. You know the type. Hell, these days we all know the type. The type has become unavoidable.

But the fact is, the way to get this across, these feelings he undoubtedly has for her, is not to have him come out and tell some woman he just met who he will probably never see in the flesh again (so to speak) that Claire is the only house he ever wants to be in. That’s rank sentimentality, something Westlake is rarely guilty of under any name. “It had been too long since he’d seen her.” That’s more like it. Believe me, he saw the problems in this book more clearly than we ever did. But for some reason it still came out this way.

If you can find a single comment he ever made about Flashfire, I’d be most grateful. I came up empty. I think he just wanted to forget about it. He talked about The Jugger so much, perhaps, because he knew a lot of his readers loved that one, so he could afford to be disparaging about it. His real failures he didn’t want to discuss at all. And the next book was, in many ways, the perfect corrective to this one.

It’s impossible to make Parker’s mission in this one make sense. If the heist is going wrong, the last place he wants to be is Palm Beach when it happens, with the cops looking crosseyed at anybody who can’t prove longterm residency there. He’s always been a bit dependent on luck, but in spite of his advance preparations, he’s going almost entirely on luck here. He’s only winning because he’s the protagonist. That’s good enough for a regular series character in this genre. Not Parker.

Westlake’s pre-publication comments about Flashfire are still up on his web site. They reveal almost nothing: http://www.donaldwestlake.com/flashfire/

Yeah, that’s playing it underneath the vest. I mean, I found a quote where he was talking about The Black Ice Score (which as you know, I consider an underrated entry in the series) as if he’d pulled off a major literary coup in creating a situation where Parker had to spend an entire chapter asking for help.

The comment you’ve linked to is more along the lines of the parodic review blurbs he wrote for Comfort Station–“This…is….a….book”

😉

Alice and Jack may be an indirect Sherlock Holmes reference. At least, the earliest story I know of that uses the trick “Fake a fire and people will grab the thing they most value” is A Scandal in Bohemia.

In years past, I’d have said that was too obscure a reference–why make a joke you know few if any of your readers will pick up on? There is no explicit reference to A. Conan Doyle at all here. But as I’ve gone back through Westlake’s work, looked deeper into it, I’ve learned that he valued implicit jokes, things he put in there for his own pleasure, and if somebody made the connection, all the better. It’s a good insight, whether you credit it or not. But I still think this subplot should have been a short story.

If Grofield had been there, he’d have made the connection. Of course, he’d have probably already slept with the rich guy’s wife. 😉

I got a bit of a Keller vibe from the hitman in the hospital, with album reviews swapped in for the stamp collecting. He even has a female broker who gives him his assignments. Maybe it’s just the genre, but I think Block may have helped shape that genre (and while we’re at it, I think John Cusack owes him some royalties).

Bless you for remembering to mention that. I noticed it too, but I was so deep in the weeds on this one, I just let it go. Of course, a hitman with a ‘broker’ probably began with Max Allan Collins and Quarry, which Block was unquestionably responding to with Keller. Block’s broker was a woman, and more than a bit sweet on Keller. No indication of that here. And yeah, I noticed the parallels with Grosse Pointe Blank as well, but so many writers on that one, I don’t know that Cusack did much besides rewrite his own lines, which actors do so love to do.

That chapter is interesting, because it’s basically poking fun at the hitman. He thinks he’s so professional, is very disparaging of the two hoods who nearly did Parker in, and he never even got close to Parker, ends up not only getting caught, but bringing down his entire organization with him (why is he carrying a gun at all?–he’s supposed to be killing an invalid in a hospital bed).

He’s carrying a gun he’s already used multiple times (which I don’t think Quarry or Keller ever did), and I honestly don’t think Westlake was any more impressed with fictional hitmen than he was with fictional private detectives–his favorite entry in that mini-genre was probably Rabe’s Anatomy of a Killer (in which the hitman is revealed to be a psychological train wreck, lacking any real self-knowledge of self-control. And of course Greene’s A Gun for Sale. But he’s not going for any such inner depths here.

And of course in the movie the hitman is a badass super villain for Statham to fight with and eventually throw out of a high window. I am all out of eyerolls where that movie is concerned.

Melander’s plan is exactly the disaster Parker thinks it is, but he’s wrong about why; the robbery part goes fine, and it’s the “safe house” that’s the disaster. (By the way, why the hell does Parker know about movie stars and Palm Beach? When he’s at home with Claire, are they watching Entertainment Tonight?) I’m of two minds about whether Parker could have made it work. He’d have realized right away that the footprints would be an issue, but that didn’t trip them up. He’d also have figured out that the cops are likely to come by, and Melander has to play the sole occupant while the others hide in a hidden part of the house, and hope Melander doesn’t make the cops so suspicious that they come back with crowbars. Not a good bet.

Parker’s point at the start of the book is that they’re underestimating how much heat a job like this would bring down in Palm Beach. There’s no telling where exactly it’s all going to break down, but it’s going to break down, because there’s too many points in the heist where it could all go wrong. They’re so giddy with achievement after pulling off the heist itself (with one less man than they thought necessary, meaning an even bigger pot for each), and so distracted by the appearance of Parker and ‘Claire’ that they let their guards down too much when it comes to the law.

They’re casually breakfasting downstairs, when obviously the cops are going to come knocking. Maybe they figured that anyone in a house like that would be given the benefit of the doubt, be granted a sort of rich people immunity from questioning. But the fact is, the local householders are going to insist on an unrelenting dragnet.

But it’s also a fact that Westlake makes one of their mistakes that they didn’t get a phone installed after telling us they had a phone installed. So it wasn’t just them who came up with a plan that had too many holes in it.

The militia is another thing that doesn’t belong in a Parker novel. But even though you’d expect them to be heavily satirized, their horrific beliefs aside, they’e not idiots. They’re a very effective and disciplined military organization, and skilled enough to save a man who’s mostly dead. Farley is annoyed that when they finally kill someone he can’t charge them, but the flip side of that is that that they haven’t ever hurt any innocents.

No, but they surely will, now that they’ve had a taste of actual military combat, and (as Elvis sees it) kicked ass. The irony is that they finally have a chance to kill somebody, and it turns out to be somebody worse than them. Though a lot more professional. Using a new kind of social monster to kill an older one. The poor guys never knew what hit ’em.

I had no problem with the militia being in the book, my problem was that their appearance at that moment in time was too much of a Victoria’s Messenger Riding event. Not that her imperial majesty would ever have had such uncouth messengers as this in her service. Well, maybe out in the colonies somewhere.

One more quick point: if we’re going to talk about crime novels set in Florida, at some point Carl Hiaasen has to come up. He’s another very funny guy, though without Westlake’s range or depth. And, man, does he hate rich people.

I also thought about mentioning Charles Willeford, who had all the range and depth in the world, and who I know Westlake admired tremendously. Willeford didn’t actually set most of his books in Florida (he got there relatively late in life), but he’d published the first Hoke Moseley book in 1984. Those were the books that made him famous, after a lifetime of obscurity and weirdly unique novels hardly anyone read. He then died in 1988. Which was such a totally Willeford thing to do, I can’t even tell you. The Shark-Infested Custard is also mainly set in Florida, and is a savagely funny treatise on the male psyche. Honestly, if there was ever a crime writer I’d be tempted to place over Westlake, it’d be Willeford. But he wrote so little. Not much of a blog.

John D. MacDonald would be Westlake’s most important influence when it comes to Florida-based crime fiction. One of his most important influences of all, full stop. Personally, what I’ve read of him so far hasn’t impressed me that much, but a lot of Westlake’s influences were along the lines of “Look at how this guy wrote and published a lot of books that didn’t suck and made a nice living into the bargain.”

I could go into a long rambling mentally distracted discursion on how Carl Hiaasen influenced Donald E. Westlake now. However, I’ve never read Hiaasen. 😉

Were your last two sentences here an allusion to the insane NYRB interview in The Hook? I hope so.

They are, but also, I’ve genuinely never read Hiaasen. Nothing against him. You can’t read everybody.

Mike, your silence regarding my Groucho quote up top is deafening. You’d prefer I’d gone with the part where he says “You can even get stucco”? Oh how we can get stucco.

I didn’t feel there was anything to add, but if you insist:

The Coconuts was the Marx Brothers’ first actual Broadway play (I’ll Say She Is was a revue, that is, a collection of skits and songs), written by genuine playwrights George S. Kaufman and Morrie Ryskind, wth songs by Irving Berlin. Pretty impressive company for four guys that make puns and break stuff. It was written as a satire on the Florida land boom of the 20s, but that means nothing to us today, and in fact little of it survived the Marx’s tendency to replace the written text with puns and stuff-breaking. (Kaufman was the one who, while watching a performance, exclaimed “My God! I think I just heard one of the original lines!”)

Making fun of Florida has a long and storied (and played and movied) history. Hiaasen, a native Floridian, insists that he doesn’t write satires — the real thing is even more dumb and corrupt than his characters. Westlake is in good company. And what can you say about a state that’s going to be underwater in a few decades where the highest value is standing your ground?

And Palm Beach, the glorified sandbar, will probably go first. I find that oddly comforting.

I’ve been to Florida twice, and Hiaasen isn’t kidding. It’s a state of weird extremes (their tourism board should make that a slogan). First time I went, it was summer, speaking of extremes. I figured I’d experienced South Carolina in summer, how much worse could Florida be? Cue laugh track.

Our purpose was two-fold–to visit a branch of my girlfriend’s Cuban family she’d lost touch with, and to see a lot of new birds. Both purposes were achieved, at the price of some very stressful driving and and some truly bizarre experiences. And the heat. My sweet Lord in heaven, how does anyone tolerate the heat? Her older immigrant relations, who had been born in a tropical country, and lived in Tampa for decades, never stopped complaining about the heat.

The lightning in summer is like something out of the Old Testament. Actually, the Israelites wandering the desert for forty years would have found Florida in summer intimidating. The denizens of Mordor would find Florida in summer intimidating. The denizens of a painting by Bosch would find Florida in summer intimidating.

Oddly familiar, meeting her family. Like when I went to a part of Ireland a branch of my mother’s family lives in, and got shuttled from one little house to another to meet yet another cousin, and got drowned in tea. Main difference is that the Cubans drown you in coffee. Other than that and the accents, you wouldn’t know the difference. Univision, Eurovision, same thing. Okay, the Cubans actually prefer baseball to soccer, that’s different.

We went to Corkscrew Swamp, one of the jewels in the crown of Florida’s great nature preserves (never made it to the Everglades). There’d been a dry spell, so no Wood Storks breeding there. We went to this little postage stamp of a city park in St. Pete’s on our way back to Tampa. There was a vast herd of Wood Storks, being fed raw frankfurters by this retired couple. We saw our first Burrowing Owls on the front lawn of somebody’s little suburban house. They just cordon off the burrow (owls that live in holes in the ground–everything is topsy-turvy in Florida), and the owls stand there by the curb like they own the place, which in fact they do. You pull the car over, camera at the ready, and they’re like “Can I help you?” That’s what I call standing your ground.

Second time, I met my parents in Orlando. They were supposed to take the grandchildren to Disney World, so they’d reserved a timeshare, and then it turned out the kids couldn’t come. I was the back-up. Have I mentioned how horrible Orlando is? All the intelligence that should have gone into civic planning went into the theme parks. The city itself is just an afterthought. There to provide motels and all-you-can-eat buffets for bewildered tourists. My dad and I went to a nearby nature preserve (created by Disney, least they could do), and saw Sandhill Cranes, and we got a bit lost, and I was worried my dad would get heat-stroke. This was in early March.

There are moments when it can be wonderful, I don’t scorn those who love it. A writer would have to be crazy not to love it, and all the endless material it provides. But somehow Westlake couldn’t quite make it work for him. I don’t think he really believed in Florida–it wasn’t the kind of setting he excelled at portraying. It works as a sort of limbo for Parker to exist between heists, but not as a place for him to work. If Westlake actually lived there a spell, I know he could have written something to rival the best Florida crime fiction. I think he’d have preferred Mordor. Or the Bosch painting.

And damn right I insisted. You added a lot, as you always do.

Hiaasen’s first (and best) juvenile, Hoot, is about greedy, corrupt developers threatening a community of Burrowing Owls.

Which was made into a pretty dumb movie, but great poster art. Burrowing Owls are much more commonly found out west, in Prairie Dog colonies, but Florida is fairly unique in having nesting pairs in heavily settled areas. There was a massive Bald Eagle eyrie just a short distance away from where we saw the owls, but it wasn’t the breeding season. A lot of the most interesting sightings we had were in built up areas. Getting harder to find areas that aren’t all built up. The Suburb Terrible or Beautiful. I think this is where we came in. 😉

Too many things in this one. After the first heist the heisters decided to humiliate Parker and leave him alive? Very gentenmanly of them. They were acting more like Victorian noble villians, too noble I’d say.

The rest of characters are either noble or Superman-ish. Parker’s trying to kill too many people at once, too many people are trying to kill Parker. The novel is a mess. Not that I didn’t enjoy it. I even enjoyed the film, because I was watching it just like an action movie before I read the novel. If I read the book first, I’d hardly saw it to the finale.

As for the wolf theory: no injuired animal would hunt down his enemies where it’s outnumbered and outsmarted and barely alive. Even non-injured an animal won’t hunt down someone if there’s a danger to its life.

Well, true–wolves don’t really have an overdeveloped sense of vengeance, to reference a very different book. It’s the human part of Parker that takes on these vendettas. But in reaction to the way human insanity upsets the equilibrium of his lupine mind. It’s not different from the other books, it’s just taken to a slightly absurd extreme–almost as if Westlake was trying to find out how far he could push this conceit–too far this time. This happens quite often in series fiction, the writer trying to one-up what he or she has done before.

Stark had always known how to avoid going over the top before now, and I believe he learned from this one, never did it again, but that will require rereading five more books to be sure.

Leaving Parker alive makes a certain sense from their POV, because they don’t want to develop a bad reputation among others in their business. If word got out they’d killed a fellow thief after stiffing him of his share, they’d struggle to find quality heisters to work with–they’d end up working with guys like Uhl and Rosenstein, who would kill them. Even possible, if unlikely, that some of Parker’s friends would come after them. Their own self-image–romantic as you say, which is an inherent part of these books, like it or not–gets in the way of what makes sense. But what would have really made sense, of course, was to tell Parker upfront what the plan was–in which case he wouldn’t have worked with them.

And c’mon, all he did was throw a bottle of gasoline into a convenience store. They didn’t need him for the little job any more than they did for the big one. And they were going to get caught and/or killed either way. If those two hoods had finished Parker in the Everglades, the trio were still screwed, because he sabotaged their arsenal. Even with working guns, odds are the only difference would have been they’d take a few cops with them. Their tragic flaw was that they always made things more complicated than they needed to be. Too many things, absolutely right. That’s what this book is about, but it’s not what Richard Stark is about. This shouldn’t have been a Parker novel, any more than “Parker” should have been a Parker movie. But it was still a story worth telling. Pity the filmmakers told it so poorly.

I don’t see where you get this business of all the other characters being noble, let alone superheroic (you can’t possibly think that of the militia men). As I said, the only characters in this book of any note who aren’t assholes are Parker, Leslie, and Farley. And of those three, only Parker really knows himself, though the other two are working on it. And to say it for the millionth time, self-knowledge is what matters most to Westlake.

It’s a very cynical book. But you remember what I said about a cynic being a wounded romantic, right?

There is one interesting moment I skimmed over in the synopsis. In the car, going to the Everglades, Parker knows his chances of surviving are not good. He thinks to himself that he might have to give up, accept defeat and death. He’s not resigned to it–he’ll make his move, see how it goes–but he’s not scared either. He’s always known this moment would come, sooner or later. Nobody runs forever.

Nobody runs forever, exactly. Why these late Parker novels are a bit disappointing is because they give a false view of how things are in the world of career criminals. The early novels gave you a fresh portrait of this world, a dark naturmortre where every danger was new and exciting. It was a dangerous world, but you could survive in there.

Now Parker is in his 60s for shit’s sake. And he’s still running like a 20 years old. Still solving the old problems. Like nothing happened. Like nothing happened to him. Every person, human or part human, by that time would wise up and started to think ahead. Not Parker who is stuck somewhere in 1966. He can be inhuman, but if he’s at least partly human he can’t be that dumb. He’d wise up.

And the world of career criminals lost its shine. You can’t run forever. Or can you? If you every time you escape death, have a comfortable life in New Jersey with a lovable woman, then maybe life of a career criminal is not that different from a posh life of a hipster daddy? Dangers to Parker’s life became sort of making a craft beer for a old hipster, just something to pass the time, nothing unusual.

Every time I start to think of the whole Parker series I get back to Butcher’s Moon. I wish Parker and Grofield both died in that novel.

See, I think you like the world of the earlier books because it’s less real. Not more. I feel the same way, but that applies to pretty much the whole genre. Because we weren’t alive then (or at least not paying close attention) we can more easily believe this shit when it’s set in the past. But Westlake wasn’t going to write a lot of prequels and period pieces. Not interested. If he was, he’d be somebody else. He wants to write about what’s happening. Parker is his way of commenting on what he sees going on around him (as is Dortmunder).

Parker, as I feel like I’ve said a hundred times, was just as much an anachronism in 1962 as he was in 2002. He was out of the 1920’s school, Dillinger, etc. And those guys only ran a few years each. The point of Parker, or one of them, is to figure out where the old school heisters went wrong and fix it.

Their biggest problem was that they liked seeing their pictures in the papers too much–Dillinger and some of the others actually wrote letters to newspapers, daring the law to get them (and it did). Too flashy. The more attention you get, the more the law comes after you (Hoover loved the press he got when the FBI killed another heister–loved it so much he destroyed Melvin Purvis, because he didn’t want to share the spotlight). Fade into the background. Don’t make waves. Lawmen get distracted, like everybody else. They’ll focus on something else, given half a chance.

“Posh life?” It’s a little nondescript vacation cottage by a small lake in Northern New Jersey–that he only lives in during the cold months. He drives whatever cars he thinks people will pay the least attention to. He uses old small caliber five shot revolvers a lot of the time. He couldn’t possibly care less about how cool he looks. Actually, he seemed to care a lot more back in the old days, wearing expensive suits and such. He was much more of a fantasy then–and if you were honest, you’d admit that’s what you want, that’s what you miss. ‘Fess up.

Also, he’s not in his 60’s. We’ve been over this. Parker and some of the other characters just moved forward in time, somehow.

Proof? In this book, men are looking at Claire at the pool like she’s the answer to their wildest fantasies–she can’t be much older than 40. She was in her mid to late 20’s when Parker met her. He’s maybe ten years older than her. If he’s in his 60’s (he’d be in his 70’s by the end of the series, with a literal chronology) she’s well into her 50’s. Good as some women can look at that age, they don’t get the kind of attention she’s getting,in a two piece bathing suit, by a pool in Miami. Lots of other beautiful women there in skimpy bathing attire. She’s getting all the looks. She’s still a young woman. Meaning Parker is (at most) a middle-aged man. And the kind of man who will stay strong and vital until very late in life. If he makes it that far.

Whitey Bulger lived as a fugitive for 16 years, after the scam he pulled on the Feds fell through–they got him eventually, but he was on the most-wanted list. He was 81 years old when they arrested him for the last time. Don’t talk to me about what’s believable. Look at the world around you. Stranger than fiction, any day.

To sum up, yes–the First Sixteen are better. But the Final Eight are damn good. Except for this one, and it’s still very readable–enough to make me run back up to the stacks to get the others we had, and then desperately set out to acquire the books we didn’t have. How can you expect me to agree these later Parkers are no good, when they’re the ones that got me hooked on Westlake?

I’m so abashed at having missed this, I’m almost tempted to do a follow-up article about it, but on reflection, the comments section here is often used to cover things I missed in the review. And this was a really huge miss. Flashfire, in a very limited and partial sense, is a rewrite of a Sam Holt novel. Well, it recycles one of the storylines from that novel, put it that way.

In The Fourth Dimension is Death, Sam Holt alters his appearance and takes on a false identity. He even gives himself an Errol Flynn lounge lizard pencil thin mustache as part of his disguise (using the tools of his trade, like wigs and false mustaches, instead of just cultivating a mustache as Parker does). He’s encouraged in this by one of his two girlfriends, Bly Quinn, in a scene very reminiscent of Parker’s tryst with Claire at the hotel in Flashfire.

Sam then travels to Miami to see the girlfriend of the man he’s been accused of murdering, hoping to learn something that will clear his name. While he’s there he gets into a fight with two Latino men he finds burglarizing his hotel room, beats them up, and one of them recognizes him as the guy who used to play mystery-solving criminologist Jack Packard on TV–“Pah-karrrr?” the man gasps.

Sam acts, in fact, very much like Parker when he’s in this persona. Very cold-blooded and effective, hiding his true self under a mask. This book was written years before Westlake started writing as Stark again, but after Westlake was ‘outed’ as being the author of the Holt books.

Sam is adopting a personality he finds repellent, alien, absurd–but he oddly enjoys the experience. At some point, somebody sees through the disguise. And shortly after that happens, he’s very nearly shot to death, wakes up in a hospital, very weak, and then passes out again.

Now your guess is as good as mine what Westlake is doing here, what point he’s making (if any), but the parallels are clearly not a coincidence.

My own take on it is that Westlake was struggling to come up with a story for this one, and he needed to get a book out, so he cobbled together a bunch of different stories from things he hadn’t published, or in this case, something he had published that was so obscure that he knew most people would never even notice. And indeed, it took me four consecutive readings of Flashfire and two of the Holt novel to even belatedly make the connection.

It probably did amuse Westlake, though, to think that here he was, having once made his least successful series character act like Parker, and now he was making Parker act like that character. Or rather, like a richer version of the character that character was playing.

And the final kicker is, I think The Fourth Dimension is Death is a better book than Flashfire. Go ahead, shoot me. See if I care. 😉

(editing) So that’s why Claire is reading Aphra Behn! Because she’s channeling the erudite Ms. Quinn. Maybe she really is a blonde this time. Except that wouldn’t work, if we’re going to contrast her with Leslie. Well, all cats are grey…..

This book also contains a reworking of a scene in Forever and a Death (née Fall of the City), which Westlake likely believed (at least at the time of Flashfire’s writing) would never see the light of day. Truly a potpourri of scenarios and ideas borrowed from earlier material.

I have to wait until June 13th to find out which scene that is. But most interesting, and consistent with what I now perceive to be the real problem with this book–it’s been stitched together out of multiple mismatching parts. We probably will never know just how many.

And that’s most atypical of Stark. Even the weakest of the Grofields feel like unitary organic pieces of work. You may see a lot of influences, but you don’t see the joins between them. Stark digests his influences, turns them into something uniquely his own.

Westlake is cannibalizing his own work for parts here. He has every right to do that, possibly to meet the publisher’s deadline, I couldn’t say. No reason that couldn’t work, and it does work here, up to a point. Just not nearly as well as the other seven books in The Final Eight. In my opinion. People get irritated when you don’t put that in there. 😉

Okay, now I’ve read Forever and a Death (but not The Fall of the City, since that’s the original unedited manuscript). And I’m blanking on what scene you’re referring to. Not when they get Manville in the car and take him to the station, right? Or the later scene involving a car?

Humor me, I’m a bit fuzzy this morning. Possible of course that the scene you’re referring to isn’t in the book I read. I don’t think it could anything from the climax of the soon-to-be-published work, but obviously don’t spill any of that. TWR will not be posting any spoilers from the final part of that book until well after it comes out.

(editing) Oh man, I am fuzzy. You already told me this. The two guys convincing Manville to get in the car with them, and one of them is up close to him, and the other has a gun on him from further off. The switch is that the thug tells Parker his partner is a great shot, and never misses. The one in Forever and a Death tells Manville that his partner is a lousy shot, and might kill a lot of innocent bystanders. Because Parker wouldn’t care about collateral damage, but Manville would. And there’s the added inducement of Manville’s concern for Kim. It’s a long way from a perfect match (the guys in Flashfire don’t even know Claire exists). Honestly, if you hadn’t pointed it out, I might never have spotted it. But you still haven’t figured out which Westlake novel (not necessarily published as a Westlake) the central hook of Forever and a Death is borrowed from, so call it an Irish standoff. 😉

When reading Fall of the City, I was very much reminded of this scene when George, trying to meet up with Kim at a café, is approached by a smiling thug, who calmly assures him that if George doesn’t come along quietly, another man stationed about fifty yards away will start shooting. The difference in FOTC is that this man cautions George that the shooter tends to miss, and might accidentally kill any number of civilians at the café. Naturally, Parker would hardly have cared about such concerns, so Westlake tweaked it.

Replied before you edited. Still not sure what you’re referring to, but I’m sure I’ll slap my forehead when you point it out.

You correctly associated Richard Curtis’s (interesting name, that) murderous Quixotic quest with that of Edgars in The Score–in both cases, they have a vendetta against a society–Edgars a small town, Curtis a great city.

But there was a story that came before either of those, wasn’t there? It wasn’t published by the time The Score came out. But it was at least partly written, lying in a drawer somewhere. Westlake had not yet decided to get it published, but he was drawing on it when he wrote The Score. So he went from that original story to The Score to Fall of the City–and Butcher’s Moon, of course. One man against The System. But in all stories but one, that man needs others to help him try to achieve his goal, and success is predicated on how well that man knows himself, and how much the society in question deserves its comeuppance. In only one story is the idea expressed in its purest possible form–one man against a planet. And now I’ve given the game away. Let the forehead slapping commence. 😉

Well, yes, that does rather give the game away, doesn’t it? Good call.

Richard, for Richard Stark. Curtis, for Curt Clark. He knew what he was doing. But I wonder if he should have made Richard Curtis his pseudonym, and named his villain-protagonist something else. That’s something we need to talk about. This could have been a much better book if Westlake hadn’t given up on it–there were things about it that could have been improved with a rewrite or two, a sympathetic editor. But those who counseled him not to publish the book probably had a fair point about it not being well-received.

So a pseudonym, but he just didn’t seem able to pull that off anymore. He missed it, terribly. It gave him a release valve for things that didn’t fit in with people’s perceptions of him as an author. The price of fame is freedom of movement–you can’t get beneath the radar anymore.

I can see it, now that I’ve read it (and remembered your reference to it yesterday). It’s a very minor thing, hardly worth talking about–except it confirms my reaction to George’s personality shift–that he finds his inner Parker. Or his inner somebody else?

Parker is simply the most idealized stripped-down version of a focused purpose-driven character Westlake liked to write about at times. Somebody who does what must be done. George’s problem is that he can’t fully embody this ideal, because he not only cares about this woman he’s only just met (but is already falling for); he cares about what happens to people he’ll never know. But that Starkian strain that wakes up inside of him when crisis strikes still serves him in good stead. As it has many another Westlake protagonist. And Westlake actually takes it a lot easier on George than he did on Parker in this book. Well, that’s because Parker can take it.

Consider my forehead slapped. Very clever. I have no doubt Westlake could have solved many of the book’s weaknesses with another pass. In Westlake’s correspondence with Knox Burger about the novel, KB expresses puzzlement over the pseudonym Westlake had submitted with the manuscript. Westlake responds that the name had just been a joke. (Sadly, the name was not recorded in the archive, either in the manuscript or the correspondence.) Nevertheless, Westlake also indicates that if they did move forward with publication, a pseudonym would be in order, and he floats the idea of using a woman’s name. Oh, what might have been.

As the book started up, I was seeing what Knox Burger meant–the characters don’t have that Westlake touch yet. They seem like stock figures in a standard page-turning suspense novel. And then, as it goes on, they all surprise you, turn out to be more than you thought they were. It is hard for the casual reader to pick up on what’s going on, though. With The Comedy is Finished, it’s a more contained narrative, and you have Koo Davis to hold it all together. And there, most of the characters are allowed to be horrible. Here, it’s more black and white–good people on one side, bad people on the other.

Here, the central character is a man planning horrendous acts, and Westlake made that work with The Ax (many parallels between Burke Devore and Richard Curtis, in spite of the class divide), but of course you’re inside Burke’s head the whole time. Westlake can’t do that here, that’s not how the form works.

I kind of wish he’d kept the female lead a Chinese woman (Asian American, maybe), but maybe he thought that was too similar to Tomorrow Never Dies (the afterword makes it clear that we owe Michelle Yeoh as a Bond Girl to Westlake, even though they didn’t use most of his ideas). Another perky blonde ingenue I could have done without, though Kim has her virtues. The subplot with her parents doesn’t really go anywhere (and yet that got left in).

He got boxed in, Mr. Westlake. It’s still a genre story, but as far as everyone around him sees it, it’s the wrong genre.

And yet Ex Officio (his first real attempt in this vein) is still evailable, and many better books of his are not. Overall, I’d say it’s the weakest of his three posthumously published books, but if he’d taken some time to rework it–oh well. We’ll talk it out soon enough. And more than once, I think.

For me, that’s the primary pleasure of the book, discovering that the characters exceed your expectations — and their own. “You’re not what I was told you were,” one character remarks to another. Well, none of them are, as it turns out.

As the Irish say (those who speak Irish), Sin-e!

Though to be sure, some characters fall very short of their expectations, and some end up in roles they’d never anticipated. I mean, pretty sure nobody ever wants to be Oddjob when he grows up. Though the hat would be pretty cool. 😉

Elvis Clagg Lives. 17 others weren’t so lucky. 😐

https://talkingpointsmemo.com/livewire/white-supremacist-leader-says-florida-school-shooter-was-member-of-his-group

This particular shooter may not have been affiliated with this particular group.

But Elvis Clagg is still out there. On social media.

https://talkingpointsmemo.com/livewire/white-supremacist-leader-says-florida-school-shooter-was-member-of-his-group

If DW could have seen the future (and I’m not so sure he couldn’t)… he almost certainly still would have gone to Mexico.

Mr. Westlake, as you know, was a Dickens reader.

It is not for spirits of any station, great or small, to change a course mortals have set for themselves. Thoughts and prayers, if not accompanied by action, are an insult to God. An attempt to pass the buck.

It is for us to sponge away the writing on the stone. Or else, we can deny the self-evident truth. Slander those who tell it to us. Admit it for factious purposes and make it worse. AND ABIDE THE END.

You know, I so badly wanted this book to surprise me, prove me wrong. I’ve heard this referred to as the worst Parker book or at least the weakest entry so many times, and I wanted to be the outlier. I feel every story (of any medium) deserves at least one person to champion it, you know? Well, having finally read Flashfire…that one person will not be me. Yeah, this installment is pretty weaksauce.

I gotta say, the dawning horror I felt when it became clear that “Parker” actually used quite a bit from this (including bits I really didn’t like) was comparable to the most eldritch reality warping beings of Lovecraft’s stories. On the other hand, though, this means The Split is no longer the worst Parker adaptation that tries to be an adaptation (again, not including the ones that barely bothered).

Granted, Westlake’s execution of these elements was significantly better than the film but that frankly should be a given? And also, even then, they’re still not that great. And I suppose I should get my biggest problem with Flashfire out of the way now:

Parker catches Leslie following him, who then goes on to explain that she wants in on whatever Parker’s planning…and Parker does so.

If you may recall my post on “Parker”, this was the moment where I essentially pounded my fist on the table and went: “No. Parker wouldn’t do that.” Despite all the other adaptations featuring fairly loose Parker variants, this was the moment where my patience evaporated, enough was enough.

Well, having read the source material, I still call bullshit. See, I don’t really mind the other “OOC” moments Parker does here because, ultimately, they’re not that different from how he normally acts. His description of Claire with the whole windows and house spiel is accurate to their relationship, even if he wouldn’t outright say it like that. Him referencing Jaws tracks too because he’s occasionally made references to pop culture before (like calling the cops Mutt and Jeff in The Seventh). Hell, it’s possible he’s only vaguely aware of the film’s plot and hasn’t actually watched it. I frankly love Parker racking up a hundred thousand dollars just for financial funding in order to commence his plan of killing Melany and crew. I have a soft spot for characters acting out of extreme spite and this is a glorious example of that. Because it’s not about the money, it’s the principle of them stiffing him and then not even having the common sense to try and kill him. I dig that, I respect that.