“You said it was Jersey plates,” Barry pointed out, and poured them both some more chardonnay. “Maybe he went home.”

“Or maybe he’s lying low,” she said. “If he isn’t a landscape designer, and I know damn well he isn’t, then what’s he doing here, what’s he doing with Elaine Langen, and why are they both lying about it?”

“Hanky-panky?”

“No,” she said, sure of that. “She would, with anything in pants, but not him. He’s a cold guy. With me, when I stopped him, he wore this affability like a coat, it wasn’t him.”

“The cloak of invisibility,” Barry suggested.

“Exactly. Who knows who he is, down in there?”

It starts with technology, but it still ends with tracker dogs.

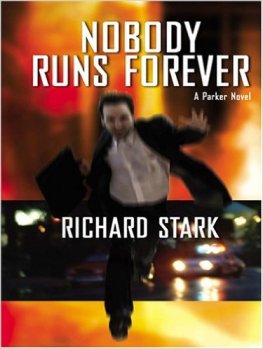

One more cover gallery, and a bit repetitive, I know, but how fortunate that University of Chicago Press finally published The Triptych. Meaning that from now on, all twenty-eight of the books Westlake published as Stark are evailable, which means they’ll stay in ‘print’ no matter what. Well, for the foreseeable future, which Parker wouldn’t think was saying anything much.

Not much to say about the cover itself, either–not sure what Parker is leaning against there. Bank vault door? Safe tumbler? I’ve no idea. The one next to it is tiresomely over-literal, and I’m not even sure who put out that edition.

Rivages, in its Thriller and Noir imprints both, chose to focus on Parker’s target–an armored car. And was perhaps alone in choosing not to use the original title. Google tells me that it would translate to Personne Ne Court Toujours, though presumably other phrasings would be possible. Perhaps none had the right ring, so they went with the above, which means ‘running on empty.’ Sound familiar?

C’est vrai. (And Parker has seen his share of both fire and rain.)

Marilyn Stasio, in her NY Times review column devoted to crime fiction (descended from the Criminals At Large column once written by Anthony Boucher, that originally championed these books), doesn’t so much review as describe. Never having been taken seriously in the past, but now possessing the authority of longevity, Stark and his chief protagonist are treated as found art, changeless relics of another time, which isn’t altogether wrong, but you miss a lot that way–it’s all been changing over time, we’ve seen that in some detail here. (And if Parker doesn’t have a sense of humor, please explain the ending of The Seventh to me, Ms. Stasio. )

The world around Parker is shifting, and he has no choice but to shift with it. The question is, how far can he adapt to the encroaching exigencies of this digital age and still remain himself? If he can’t go far enough, how much longer can he last? Is he running on empty? He wouldn’t be alone.

This book is hard to figure, and that’s because it’s not a book. It’s one third of a book. Three novels that form one trifurcated epic. Not a trilogy, but a Triptych, as I said, as Westlake belatedly realized.

Like Butcher’s Moon, the blood-drenched epic that concluded the First Sixteen (which isn’t divided into sections at all, just fifty-five chapters of ever-switching perspectives), this longer, bleaker, more contemplative and far less sanguinary conclusion to the Final Eight just doesn’t fit the profile. But unlike Butcher’s Moon, it pretends to.

We did the multi-POV round-robin thing in Part Two, each chapter from a different character’s perspective. Part Three sticks with Parker and his colleagues. But then there’s Part Four, which flouts the established protocol altogether.

In the fairly long first chapter of Part Four, where the heist finally goes down, Stark is just floating around in the ether, like a hovering hawk with x-ray vision, showing us everything happening at once, checking in on everybody who still matters in the story. He can do what the frustrated heist planner in Westlake’s Castle In The Air can only fantasize about.

What Eustace wanted, what Eustace needed, was for the entire city of Paris to suddenly be reduced to the size and aspect of a model train layout, with himself on a high stool overlooking the whole thing.

Much easier to do for a lightly peopled corner of New England, late at night, but still a tricky balancing act for any writer. Westlake had done something like it in a few chapters of Dancing Aztecs, though in a more lyrical form. (If you want to see that form done to perfection in a recent novel, I shall again plug Sarah Perry’s The Essex Serpent).

This really should have been released as one volume, and I hope it will be someday–you can’t properly appreciate any one panel in The Triptych without the others to refer to. To split them apart almost amounts to art crime. That I hold these three final installments of the Parker Saga in higher estimation than some probably stems from the fact that I read all three in quick succession. As individual books, they must always be somewhat unsatisfying, for all their undoubted merits. Their cumulative impact is exponentially greater.

As a unified whole, they are still far from perfect: the author was starting to falter, his race nearly run–but you understand them much better that way, how each complements the other. I don’t know how close together Westlake wrote them, but he certainly came to understand along the way what he was doing here, quite different from anything he’d done before.

A pity that publishing schedules demanded they come out so far apart. I broke my usual rule of reviewing books in order of publication for this very reason. Let’s see how many more rules I can break before we’re done here.

Another way in which this book goes against the grain is that Parker is less involved in planning. Dalesia seems to have a knack for that as well, so while he’s been out scouting for the spot where they hijack the armored car, and the hideout where they can chill with the cash afterwards, Parker has been rustling up some ‘materiel,’ a phrase I don’t think has been used in a Stark novel before.

Remember Briggs? He showed up briefly at the start of Butcher’s Moon, the jewelry store heist that went wrong–he was the guy Parker told to throw a bomb to cover their escape. He had to throw it in the direction of Michaelson, their fallen comrade, who might still have been alive, but not after the bomb went off. Ruined his nerve, and he retired. Well. As much as a Stark heister ever can retire. He and his wife have a nice little house on a lake, just like Parker and Claire. But this one’s in Florida.

Watching the movement on the lake, Parker said, “You like things calm. No commotion.”

“We get commotion sometimes, Briggs said. He’d put on a few pounds but was still basically a thin unathletic man who looked as though he belonged behind a desk. Nodding at the lake, he said, “A few years ago, a tornado came across from the Gulf, bounced down onto the lake, looked as though it was coming straight here, lifted up just before it hit the shore, we watched the tail twist as it went right over the house, watched it out that picture window there. That was enough commotion for a while.”

Parker said, “You watched it out a picture window?”

Briggs either shrugged or shivered; it was hard to tell which. “Afterwards, we said to each other, that was really stupid.”

Anyway, he’s still got connections, which is why Parker is here. They need something along the lines of a bazooka, or an RPG–powerful enough to knock out a heavily armored vehicle–and they’ll need several of them, no time for reloading. They also need assault rifles for the aftermath. (No, I don’t know why they can’t just go to a gun show, or rob a Walmart, stupid modern reality screwing up my crime fiction. The Second Amendment doesn’t apply to calm professional crooks, only psycho-zealots with death wishes, how’s about that?)

Briggs mentions something about how the Feds are paying a lot more attention to weapons dealers now, because terrorism. Now that could have been true in the 90’s (the first World Trade Center job), and nobody mentions 9/11, but it’s pretty strongly implied that we’re living in a brave new world that includes a Department of Homeland Security. Anyway, he knows some people with just the can opener Parker needs. The Carl-Gustaf. (The hyphen seems to be a mistake, and who cares?)

“Sounds like a king,” Parker says. Because it’s named after one. Just another Saab story.

(This is an old design, with many variations, no need for us to know which one Parker’s getting. You can see Westlake trying to avoid too many specifics–still going to get irate letters from anal weaponry buffs, but keep it to a minimum. “No, it’s a grenade firing system!” Now they’ve got the internet to kvetch on. I bet none of them have slept for a week.)

With an assurance from Briggs that he’ll get them the materiel in time, Parker heads back to Massachusetts, and hears about Dalesia recruiting McWhitney (and of the untimely demise of Mr. Keenan). He’s fine with both developments, though he’s a little worried about McWhitney’s tendency to fly off the handle–the guy seems okay in a crisis, going by what happened at the card game, and they don’t have time to find anyone better.

Parker likes the spot Dalesia picked for the trap to be sprung, and he also likes the hideout–an abandoned church on a little-used two-lane road. There’s a place they can hide the armored car, and it’ll be invisible from the air.

What follows is a lot of professional-grade threatening, because too many people know about this job–unavoidable, but no less annoying for that. Parker has to threaten Elaine Langen, who is spooked by all the attention she’s getting from Detective Gwen Reversa, which she brought on herself by shooting Jake Beckham in the leg when nobody told her to do that. She’s not sure she can hold up under questioning. Parker reminds of how she accused him and Dalesia of playing good cop/bad cop with her. She says so far Reversa is being the good cop, and there’s no bad cop.

“Yes, there is,” Parker said. “Me.”

The look she gave him turned bleak.

Parker said, “Everything she says to you, every hour she spends on you, just keep reminding yourself. This is the good cop. The bad cop is out there, and he’s not very far away, and he doesn’t go for second chances.”

“I’m sure you don’t.” Her voice was now a whisper, as though all strength had been drained from her.

“The bad cop is nearby.”

She closed her eyes and nodded.

“Talk to the good cop all you want,” Parker said. “But always think about the bad cop.”

“I will.” “Whispered again, this time almost like a prayer.

Then he refers to the make of her car. Infiniti. Means forever. Worth going for, right? And people say he has no sense of humor. Nobody puns forever.

Next he talks to Jake’s sister Wendy, asks her to give her brother a message for him. She’s not happy about even peripheral involvement in some illegal act, straight as a die this gal, but her main concern is Jake, because like I said last time, she needs a project. And while she’s no genius, she’s got good instincts for people–she’s noticed this Dr. Myron Madchen, hanging around her brother at the hospital all the time, when there’s no reason for it. It’s making her nervous. Parker thanks her–says that makes him nervous too. Someone else to threaten.

As he drives away from the trailer park, he realizes there’s an old beat-up Plymouth Fury tailing him, and if you’ve read Dancing Aztecs, you know who is likely as not to be driving one of those. State cops. It’s Reversa. He tries to shake her, but she’s too good. Finally pulls him over. She wants to talk.

He’s got good phony ID, identifying himself as Claire’s brother, John B. Allen (possibly a reference to a 19th century western politician who has a street named after him in Tombstone AZ, I wouldn’t know).

Says he borrowed the car because his was in the shop. He’s a landscape architect. Well, after a fashion, I suppose that’s true. The car is clean, his ID doesn’t set off any alarms, she’s got nothing to hold him on, so she lets him go, and he resolves to ditch the Lexus, find something else to drive. He knows she suspects him, and he can see this is a smart cop. And here’s a little plot hole.

See, we’ve already been told that Keenan and his partner tracked Parker down by running the plates on the Lexus–using databases maintained by the law, which they can access as what you might call a professional courtesy. So once it becomes obvious that ‘John B. Allen’ was involved in a bank robbery, how hard is it going to be for the law to zero in on the house in New Jersey?

Okay, maybe there’s a workaround (he’s going to tell Claire to report the car stolen), but seems like a bad idea for Parker to have gone there on a job, in a car registered to Claire, unless the registration was for a false address, which would be equally problematic. Oh well, let’s see how that plays out further down the road. It’s not going to matter for the immediate future.

Parker and Dalesia go to Madchen’s house, and terrify the hell out of him. He’s going to stop hanging around Jake. So he’s nervous, fine. He needs his cut out of Jake’s share to get away from this life he hates, no problem. But he’s only putting them in a situation where they’ll have to kill him just to neaten things up. We learned in Part Two that he’s been on the verge of suicide for a while now–and wants to live, more than anything. Parker is convinced he’s too scared to go to the cops, so they let him off with a warning. This time.

Now it’s time for them to be threatened, by someone as professional as they are, albeit in a somewhat more legal profession. Sandra Loscalzo, the late Mr. Keenan’s partner. Not of the Hammett school, she doesn’t feel like when a woman’s partner is killed she should do something about it. She just wants the same thing Keenan did–the reward money on Harbin. She was always the brains of that outfit anyway.

She holds McWhitney at gunpoint, at the motel all three at staying at–has him call the other two in for a confab. The other side of the coin from Gwen Reversa–also tall, slender, blonde, very attractive (this leads to some confusion, when McWhitney tells the others about this woman following him). She’s right on the edge between legal and illegal.

Oh, and she’s gay. She lets slip (for no reason I can see) that she lives in Cape Cod, has a mortgage on a house there, where she lives with a friend who has a little girl going to private school. To which Parker says “To find a dyke on Cape Cod with a daughter in private school and a canary-yellow-haired roommate would not be impossible.” It would if she shot them all dead with her .357, but it’s a small motel room. She knows better. So do they. They work out a deal.

McWhitney will get her Harbin’s mortal remains (Keenan’s she could care less about). She’ll get all the reward money herself, no partner to split it with. She knows they’re planning a job, but she doesn’t care about that, none of her business, she’s just an implausibly hot skip tracer (heavy heisters don’t skip bail, because they don’t make bail). Seems like there’s really nothing she cares about but scoring big and heading back to the woman she’s shacked up with. Hmmm.

Part Three ends with Parker seeing Wendy Beckham sitting in her little Honda, parked by the motel. She knows about the bank job, and now that she knows they’re staying at the very same motel Jake works at, she figures there’s no way in hell her little brother isn’t going to jail again if they pull the job. (Of course, if he’d done what Parker told him to do in the first place, break parole and turn himself in, but Parker isn’t going to bring that up now.)

She’s got a point, but Parker’s got a better one. He tells her that if she’d talked to this other guy in the string, who tends not to think things through (I’m going to assume this is McWhitney), he’d just shoot her right then and there. But that’s not the threat. He knows she’s brave enough, and devoted enough, and dumb enough to risk all that.

Here’s his final and most sophisticated threat. Threats, you see, have to be tailored to the person being threatened. What is this woman most afraid of?

Parker said, “The reason it’s better to tell me than this other guy is, I take a minute to think about it. I take a minute and I think, “what is she gonna tell the cops? Does she know when or where or how we’re gonna do it? No. Does she know who we are when we’re at home? No. The only thing she can do is blow the whistle on her brother, so instead of maybe he’s in trouble definitely he’s in trouble and you did it.”

He waited, watching her eyes, as she went from defiant to frightened to something like desperate. Then he said, “You want to talk to the cops, go ahead. Don’t worry about us. I gotta pack now. Goodbye.”

Part Four, Chapter One, is the most exciting part of the book, and the most free-ranging. Divided into thirty-seven segments, no more than two or three pages apiece, some no more than a paragraph, each divided from the others by short horizontal bars centered on the page. I guess I could follow suit, just to be different.

_______________

The pack, on the hunt now, departs the fittingly named Trails End Motor Inne (sounds like someplace Burke Devore might have stayed on one of his hunts, in The Ax), while Jake and Wendy contemplate a dwindling set of options at the hospital. Jake says he’s sorry he told her about it. So is she.

_______________

Parker meets Dalesia and McWhitney at their staging area, an old abandoned mill. They’re waiting for Briggs and the materiel. If Briggs doesn’t show, it’s all off.

_______________

As they wait, four International Navistar Armored Cars, model 2700, are getting started for Deer Hill Bank, coming from Chelsea, just outside Boston. Four big boxy vehicles like this one.

_______________

Dalesia heads off to meet Briggs at the motel, and lead him to the staging area.

_______________

The armored cars, on their way upstate, head onto the Mystic-Tobin Bridge. (Why am I hearing Van Morrison in my head?) Most people just call it the Tobin Bridge. It’s not just a metatextual reference to Mitch Tobin, though of course it is that as well. It exists in physical reality. Here, I’ll prove it.

_______________

Dalesia comes back to the mill with Briggs, who arrived on time, with the goods. McWhitney’s the only one who doesn’t know him from past jobs. They shake hands, neither convinced the other is okay. Both were generally dissatisfied people, in different ways, and couldn’t be expected to take to each other right away. Awkward, introducing people you know from different places in your life. We can all relate.

_______________

Elaine Langen heads for the banquet that celebrates the destruction of her father’s legacy. She hopes to be celebrating something else soon. But she’s nervous. Holding herself together with Valium and liquor.

_______________

Briggs introduces the team (and us) to the ordinance he’s acquired, sounding like a sales rep, which is what he is. The three Carl-Gustafs (geez, they could knock over a small country) have three methods of sighting; the useful one here will be infrared. He was going to get them Valmets (remember them from Good Behavior?), but he could only find the ones without trigger guards (for Finnish soldiers wearing mittens), and he figured that would not be a good idea. So the assault rifles are Colt Commandos–basically short-barreled M-16s. I don’t feel like posting an image. Too soon, you know? Or do I mean too late?

_______________

Elaine stands there while her shit of a husband openly gloats about what he’s done to daddy’s bank. She needs another drink. Open bar. Uh-oh.

_______________

At the Green Man Motel, Dr. Myron Madchen and his girlfriend Isabelle Moran, make love to celebrate their impending delivery from unsuitable spouses. They have to make love carefully because of the broken rib her shit of a husband recently gave her. Westlake recycling the love scene from that novel he recycled from a rejected Bond script; a book he figures nobody will ever read. Fooled you, didn’t we, Mr. Westlake?

________________

Briggs heads back to the motel, where he’s supposed to rest up in Dalesia’s room (no need to register that way) before going home to Florida. McWhitney says it would be nice if the rent-a-cops just gave up when they saw the Commandos. Dalesia opines that they have to put up some kind of token resistance, just to feel okay with themselves afterwards. Parker says the only stupid thing the uniforms could do would be to shoot at them, since that would get them all killed. Dalesia points out that Parker’s going to be in a borrowed police car, so nobody will be shooting at him. “It’s still stupid,” he says.

_______________

Also at the Green Man Motel, Sandra Loscalzo comes back to her room and switches on her police scanners. She doesn’t want to stop the heist, doesn’t even know what exactly is being heisted, but if there’s a way to include herself in, she’s going to find it.

Sandra had once heard a definition of a lawyer that she liked a lot. It said: “A lawyer is somebody who find out where money is going to change hands, and goes there.” It was a description with speed and solidity and movement, and Sandra identified with it. She wasn’t a lawyer, but she didn’t see why she couldn’t make it work for her.

_______________

Elaine is really drunk now. If you were forced to watch a lot of bankers give speeches, so would you be.

_______________

Wendy calls Jake at the hospital. She wants to give him a pep talk, about how he mustn’t give up, just deny everything, she’ll get him a good lawyer, etc. And when she means if they catch him out, he can always tell the law everything he knows about these guys who like nothing better than exterminating rats, to get a shorter jail sentence. (This is her way of encouraging a man who couldn’t even face two weeks in a county lock-up to establish an alibi). So buck up, baby brother! By the time she’s done, she’s annihilated whatever nerve he had left.

_______________

Briggs is at the motel, but he can’t sleep. He’s pacing around like a caged animal. The MassPike is right outside, and he wants to be on it, even though he’s exhausted from the long drive. Retired from active service though he be, part of him wants to join in.

It was the job those three were on; that’s what had agitated him. He’d been away from that business a long time, and he’d forgotten the rush it involved, the sense that, for just a little while, you were living life in italics. You weren’t really aware of it when it was happening to you, but Briggs had seen it in Parker and Dalesia and the other one, and he’d found himsel envying, not the danger or the risk or even the profit, but that feeling of heightened experience. A drug without drugs.

Like any addict, he’s got to get away from the opportunity to relapse. So he hits the road. Having reminded us all why we’re reading these books.

_______________

On his way south, Briggs passes a nice restaurant, and who should be there but Detective Second Grade Gwen Reversa and her criminal defense lawyer boyfriend, Barry Ridgely, about who Gwen knows everything there is to be known, because she checked him out like a potential perp after the first date. They talk shop, of course, and she tells him about her encounter with ‘John B. Allen.’ That quote’s up top, ending with a very good question. And for all the words I’ve typed here, I don’t really know the answer for sure. Did Stark?

_______________

Elaine’s had enough. In several senses of the term. She excuses herself, and walks to her Infiniti parked outside, trying to look sober, and not succeeding.

_______________

The armored cars are still on their way. Parker and the other two have dinner. At a diner. Not the one at the intersection where they’re going to lie in wait shortly. That one doesn’t serve dinner.

_______________

The armored cars pull into the Green Man Motel, where Myron and Isabelle are just kissing each other good night. The security men are going to take a quick nap, then head for the bank at around 1:00AM.

_______________

Having eaten, the crew needs two cars for the job, not being dumb enough to use their own. They steal an old rustbucket from a used car lot for McWhitney and Dalesia to drive, and then Dalesia takes Parker to some miniscule Hamlet that can’t even afford a regular police department, but gets enough ski traffic in the winter as to need to hire two retired cops for a few months each year–and the rest of the year, their only squad car is in a garage behind the town hall. Won’t be missed for a while.

_______________

At Deer Hill Bank, it’s time to start packing everything up to be loaded into the armored cars. Elaine’s supposed to be there, to see which car has the cash. She’s home, sleeping it off. Elaine, you had one job……

_______________

Jake was so agitated from his sister’s pep talk, they gave him a pill. But he just refuses to chill.

_______________

Parker is in the squad car. Not the first time he’s driven one of those. Not as good a string as the one in Copper Canyon. Then again, the finger on this job isn’t out to destroy a whole town. Just herself, mainly.

_______________

Sandra is glued to her scanners, and she’s starting to pick up chatter relating to the armored cars. Cops clearing the route. She can tell something’s up, but she’s not sure what. Yet.

_______________

Dalesia gets the truck to transport the cash in once they dump the armored car. Rented with McWhitney’s credit card, the one related to the bar he owns. Back to the factory, where McWhitney is waiting with the stolen Chevy Celebrity. The name of a real car make. This isn’t a Dortmunder novel.

_______________

Sandra sees the armored cars leaving the motel, figures there’s a connection, but can’t get to her own car in time to follow them, so she goes back to the scanners.

_______________

Elaine doesn’t show at the meeting spot where she was supposed to give Dalesia the number of the money truck. Surprise. He races to the ambush spot, and tells Parker. Parker gets into the pick up, and directs him to the Langen home. Elaine’s got some ‘splainin to do.

Frightened as she is to see Parker standing by her bed, she’s even more horrified to realize how much she screwed up. She’s got to drive back to the bank, where the party is long over, and get the truck number. She repeats it all the way back to where Parker is waiting. “One-oh-two-six-eight.”

_______________

Jake’s starting to wake.

_______________

Sandra has gotten a rough idea of the route the armored cars are taking, and you remember her favorite quote about lawyers. She’s going to try and be there when the money changes hands.

______________

Everybody’s getting in place now. Soon.

_______________

Sandra sees two police cars, one parked by a diner at an intersection, apparently empty. The other has real cops in it. The first one isn’t empty.

_______________

Filled with panic and pain-killers, Jake decides he’s got to get out of the hospital, run away, can’t go back to prison, not ever. He’s not fit to walk yet, but he somehow manages to get his clothes on, and inch his way down the staircase on the seat of his pants. It takes a long time. But he’s outside. No hospital can hold Jake Beckham!

_______________

Jack watches in satisfaction as his life’s work of destroying his father in law’s life’s work is completed. He’s mainly just worried about the bonds and securities–there’s a lot less cash than before, because they’ve been letting people take it out without putting more back in. Somebody says he thought he saw Elaine’s car. Jack says she’s asleep in bed. He’s happy to think of the misery she’ll feel tomorrow. You know what misery really loves, Jack?

_______________

Dalesia and McWhitney are where they’re supposed to be.

_______________

Sandra is where she’s not supposed to be, which we gather is where she always wants to be.

______________

Jack Langen drives with a few other bank officials, to the new improved home of the Deer Hill bank’s assets. Shorter route than the armored cars are taking, they’ll be waiting when the money arrives. He’s playing Sinatra. Thinking about that future trophy wife. Forgetting the current wife.

______________

Sandra is right on the spot when the Carl-Gustafs lay down their royal edicts. Chaos ensues. A squad car appears out of nowhere–looks familiar–three of the Navistars are totaled, the mystery squad car cuts the fourth one out of the herd, using the loudspeaker to direct it away from the carnage, to safety, right? No, that can’t be right. That car’s a ringer! It’s the crooks! She’s an officer of the law. You know, kind of. Okay, not really. More of a relic of America’s frontier history. Cue the identity crisis.

She had to tell them; she had to let them know. The story isn’t here, with these blocked roads and burning trucks and dazed people. The story just went away with the only armored car that wasn’t hit. Get after that phony cop. She actually had her hand on the door handle, shifting her weight to get out of the car, when she thought again. Wait a second. Whose side am I on here? If those are my three guys–and who else could they be?–I don’t want them arrested, I don’t want them in jail. That way I’d never get the proof I need on Mike Harbin.

Keep going, fellas, she thought, as she put the car in reverse and U-turned backward away from there. Keep going and I’ll see you in a couple days.

Quickly the fires shrank and then disappeared from her mirror.

Reminds me of this time I saw a Red-tailed Hawk and a Cooper’s Hawk in the same place, and there’s bad blood there, family feud, you know? But then this murder of crows showed up, started chasing the Red-tail, because they like to chase all hawks, and the Red-tail was bigger and slower, they could attend to the small fry later. They don’t want these hardened predators robbing nests they’re supposed to be robbing. Crows are simultaneously the crooks and cops of the bird world.

The Coop, about the same size as a crow, joined in with the mob for a moment, caught up in the excitement of the moment. But then you could almost see a thought balloon appear over his head–“What am I doing?” and he darted off the other way before the crows noticed him. It’s a bit like that. Except the Red-tail wasn’t going to meet up with him later so they could do business. I never said it was a one-to-one analogy.

So that’s Chapter 1 of Part Four. Six chapters left in the book. We’re over 5,000 words. Why don’t we cut it short here, and synopsize Chapter 2 next time, as this eight part review of a 295 page novel continues. Happy Columbus Day.

(I had you there a moment, admit it.)

In spite of all the little personnel snafus with Jake and Elaine and Myron, the heist went off like a dream, everything happened the way it was supposed to, and they got away clean with the cash. Zero fatalities. The disoriented men in the truck put up no fight at all–what little nerve they had left, McWhitney scared out of them with his psycho act that isn’t 100% an act.

This would normally be the part of the book where one of the partners turns on the others, or some interloper tries to get the loot away from them, because nothing can ever be easy for Parker. There has to be a hitch. This time it’s the law. That’s a switch.

They make it to the factory in fifteen minutes, switch the cash to the rented truck in under ten. And as they head for the church to hole up, they hear choppers overhead. They split up, to avoid attention. On the way there, Parker sees Dalesia with the rented truck, waiting for a break in the chopper surveillance, since a truck’s what they’ll be looking for. When Parker arrives at the church, McWhitney is already there, looking even more irate than usual. “I don’t like how fast they’re being,” he says.

They planned for every contingency–except the new communications tech. Except massive terror attacks ramping up readiness. A machine built to stop Al Quaeda is being used to swat flies. And thing is, because of the hardware they used, the law can’t be sure they’re not Al Quaeda, or something like that.

Law enforcement in recent years had come to expect an attack from somewhere outside the United States, that could hit anywhere at any time and strike any kind of target, and they’d geared up for it. Because of that, the few hours Parker and the other two had been counting on weren’t there.

The church is a solid hideout, but it’s not set up for them to stay there a long time, because they’d never planned it that way. The plan was to get out of the area before the net closed. Could they get away? Sure. With the cash? Not a hope.

Parker improvises in the clutch, perhaps his most valuable talent. The choir loft is full of boxes full of hymnals, similar to the ones the money is packed in. Put the boxes up there. Put a layer of books over the cash. Leave. Come back later. They pack up and go, in three different directions. Parker hits a roadblock after a few miles–his ID holds up. This time. He’s got four thousand in cash from the bank in his pocket. He finds a diner and sits down to eat.

There’s a TV showing the news there. Parker sees Myron Madchen at a podium, making a statement to the press, with his lawyer standing next to him. They got Jake. Of course. He talked. Of course. What he said was not very coherent, but still pretty incriminating. Madchen is there to talk about his patient–but he himself is a person of interest, as they say.

His lawyer says it’s very wrong to cast any suspicion on the good doctor in his hour of bereavement–his wife just died. Of a heart attack. He’s in shock–never saw it coming. Parker doesn’t have to be much of a detective to solve that mystery.

Gwen Reversa is on next. She’s going to make first grade in no time. Taking a modest little bow for having sensed something funny about Elaine Langen, who is now in custody. Not quite the way Elaine wanted to get revenge on Jack, but something tells me that providing your wife with information used in an armored car heist is not the fast track to success in the banking world.

Then they show a police sketch of ‘John B. Allen’–presumably drawn from Reversa’s very distinct memories of that brief encounter with Parker.

They think that’s me, Parker thought, and studied it, as the interviewer’s voice, over the picture, said, “This is almost certainly one of the robbers.”

An 800 number appeared, superimposed over the drawing. “If you see this man, phone this number. Rutherford Combined Savings has posted a one-hundred-thousand dollar reward for the capture and conviction of this man and any other member of the gang, and the recovery of the nearly two million, two-hundred thousand dollars stolen in the robbery.”

Parker looked up and down the counter. Half a dozen other people were gazing at the television set. None of them looked to be ready to go off and make a phone call. It seemed to him, if you told one of those people “This picture is that guy. See the cheekbones? See the shape of the forehead?” they’d say, “Oh, yeah!” But if it wasn’t pointed out, they’d just go on eating.

Parker has never been much impressed by the drafting skills of police sketch artists. Reversa didn’t have a dash cam when she stopped him in her plainclothes Plymouth Fury, or it might be much worse. Parker pays the check and walks out. It’s much worse. There’s a squad car parked by his Dodge.

John B. Allen. One computer talks to another, and it doesn’t take long. He’d been moving through the roadblocks just ahead of the news. John B. Allen is wanted for robbery over here. John B. Allen rented a car over there. Let’s find the car, and wait for Allen to come back to it.

He strolls towards the trees by the parking lot.

Final chapter. Well, it really could be this time. Chapter 7. Don’t tell me Stark doesn’t have a sense of humor either.

Parker is climbing the increasingly steep wooded slope by the diner, stopping here and there to look down, check out the situation. He’s thinking as he goes that the bank people are lying about what they got, they always make it more. The haul was just a bit over a millon, he’s sure.

Less than expected. Nowhere near enough to bankroll the escape fantasies of the comedy team of Elaine, Jake, and Dr. Myron, not that it matters now. Still, Parker’s biggest score ever, if you don’t factor for inflation, which of course you do.

His idea is he’ll wait for them to decide he’s not coming back, then go back down, maybe steal another car, catch a bus, something. Not gonna happen. Oh, there’s a bus, all right. Well, a van. Full of dogs. Parker’s bane. He’s always feared them, more than the humans and their machines. So much more focused. So much harder to fool. One or two he can handle. Not a pack. With armed handlers backing them.

He doesn’t wait for them to come out of the van. He’s seen this movie before. You will detect a note of angry sarcasm in his thoughts as he clambers upwards, as relayed to us by Stark.

Soon he heard them, though. There was an eager note in their baying, as thought they thought what they did was music.

Parker kept climbing. There was no way to know how high the hill was. He climbed to the north, and eventually the slope would start down the other side. He’d keep ahead of the dogs, and somewhere along the line he’d find a place to hole up. He could keep away from the pursuit until dark, and then he’d decide what to do next.

He kept climbing.

“As though they thought what they did was music.” I guess everybody really is a critic.

When this book came out, people were heard to wonder out loud–mother of mercy–is this the end of Parker? It could have been. Westlake was maybe four years from his own end when it came out. If he’d put off writing the next book much longer, this would be the finale, and we’d be debating that very question in the comments section.

But just as in Breakout, when he got Lyme Disease in the middle of writing it, kept typing feverishly until he’d gotten Parker out of jail, Westlake couldn’t leave Parker there on that hillside, the dogs closing in for the kill.

Not literally, of course–they must be bloodhounds, German Shepherds don’t bay. Bloodhounds won’t do much more than lick you when they catch up, but you know what I mean. Whether he goes down in a hail of police bullets, or gets taken off to prison forever–he’s over. The second fate would be the worst. There’s a reason he didn’t kill Jake Beckham for not following his alibi instructions. The inability to suffer confinement is something he can understand. He said so at the time.

Now he’s going to have to understand somebody else. Somebody much more like–well–us. Parker is crossing much more than the border between Massachusetts and upstate New York as he climbs that hill. He’s crossing the line between his world and a place we’ve never really seen him in before, for any great length of time. What he would call The Straight World.

Not so straight as he might think. If he gets lost, he can always ask directions from the parrot.

I’m glad you spotted the plot hole. It’s hard to miss because it’s a big one, one that’s made worse by the events in Dirty Money. I mean, first of all, why is Parker driving Claire’s car around the area he’s planning the heist? Sure, maybe it’s harder than ever to acquire a “mace,” an illegitimate car that will nonetheless stand up to surface scrutiny. (Incidentally, I’ve never encountered the slang term “mace” outside of a Westlake novel. I wonder sometimes about its origin.)

But the moment Parker is pulled over by Gwen Reversa, it should be game over. He tells Claire to report the car stolen, and that seems to work, but should it? Reversa seemingly dismisses the stolen car as irrelevant in that television interview. But do I buy that Reversa never follows up on the stolen car report? Do I buy that she never even tries to find out who reported the car stolen and when? I don’t, not entirely. She’s too sharp and methodical for that. The stolen car is a lead, and if she spent five minutes pulling on that thread, she’d likely find out (in a couple of books) that the car’s owner had a visit from the FBI, because Nick Dalesia had called her house before the heist. (Okay, maybe the world has outgrown the Joe Sheer/Handy McKay communication method, but Parker: burner phones are a thing.)

With a little more digging, Reversa might even find out (also a couple of books from now) that Claire had booked a room for herself plus one at a nearby B&B. Suddenly, Claire would look like a very promising lead indeed. And yes, the folks looking at the Nick Dalesia phone call piece were federal and Reversa’s only state, and maybe there’s a breakdown in communication there, and I guess it’s possible that nobody puts all that together. (Real-life history demonstrates that it’s more than possible.) But shouldn’t it occur to Parker that Claire’s in jeopardy? I know Claire doesn’t want to move. She’s made that quite clear in more than one of the books. But all it would take would be two agencies comparing notes, and suddenly her world comes crashing down (and by extension, Parker’s).

If I bend so far backwards I’m winning the World Limbo Championship (cue the Calypso!), this is what I come up with–

Parker only got pulled over by Reversa because Elaine shot Jake in the leg, instead of just telling him to do what Parker says, at which point he’d have told her he had the alibi thing (sort of) settled. Parker knew she was a problem, but he didn’t know how much of one. Neither did she.

You remember The Green Eagle Score. Parker knows Ellen Fusco is going to see a psychiatrist. She knows about the heist they’re planning. She’s made it abundantly clear she does not want Stan to be in on this, is terrified she’s going to lose him. It never once occurs to Parker she might tell her shrink about what’s upsetting her. Because his understanding of how our stupid minds (stupid! stupid!) work is always going to be incomplete. He studies us, and figures things out after the fact.

They were always going to use other cars for the heist. Probably it is hard to get a reliable mace now, with police databases being so interlinked, and all kinds of digital ID built into the cars. You can be sure he never speeds, and comes to a complete stop at every intersection. The car was so immaculate, there was nothing for Reversa to use as an excuse.

If it hadn’t been for Elaine, the Lexus would have been no problem, and it wouldn’t raise any red flags at roadblocks afterwards. And nobody suspects the white guy in a Lexus. Unfair, but true.

Most of what he’s doing here would have worked fine back in the late 60’s/early 70’s–and in a weird way, that’s where he still is. Time warp. In his mind, the events of Butcher’s Moon happened just a few years back, not three decades ago. You can’t rationalize it, because it’s not rational. It’s a literary conceit. Parker has always, to some extent, been an anachronism, a man out of step with his times. He’s just as tech-allergic as Dortmunder. And he doesn’t have a Kelp.

I seem to recall that in the final book, Claire is steeling herself to give up the house. Not happy about it, but willing. Her increasing involvement in Parker’s work is a red flag all in itself, and I think if there’d been a book after that, the flag would have been waved. Something’s got to give. And Claire has been Parker’s most vulnerable spot for a long time now. She’s his Blanca. I shouldn’t need to explain that by now.

This Triptych is where Parker is forced, most unwillingly, to confront the 21st century, update his tradecraft yet again, and what the final outcome of that encounter would have been, we can only guess.

(Would you by any chance have the phone number of a good chiropractor?)

When it came out, I was frustrated by this book. Writing about it back then, I noted that Westlake was having trouble with his vision, and was undergoing a series of operations on his eyes. I can’t remember where I learned that, and I can’t find any reference to it now. I speculated (at the time) that his ongoing vision problems had contributed to some the problems with NRF. But after the next two books were released, I was feeling relieved. It seemed to me that Stark had given new shape to his story, tying off all the dangling plot threads (save the one mentioned above). Writing about all three books in 2008, I suggested that Westlake was surely feeling better. “The job is done,” I wrote, quoting the man himself, from his blog entry about Dirty Money. Little did I know how accurate that statement was.

Like to see that review. There was probably more good criticism about these three than there was for most of the previous novels in the series, because, as I mentioned, there was a certain venerable aura around Parker by now. Yesterday’s trash, today’s treasure–but this was gold from the start.

I think I remember seeing a mistake in Dirty Money, some minor thing, but I don’t remember what. Well, should know by the end of the month. Planning to finish Ask the Parrot in two, Dirty Money in one, and publish the Get Real review the same day as Dirty Money–whichever one comes last will be my 201st article here. I did not plan that.

It’s the center panel of the Triptych that has my deepest admiration. That being said, it really is one piece of work even though it wasn’t planned to be. I think you hit it dead square center–he kept writing until he’d fixed most of his mistakes, or at least negated them to a certain extent.

The mind is obviously still razor sharp, so eye problems are as good an explanation as any. But an increase in brainfarts is an unavoidable consequence of old ge.

It wasn’t a full review; just some thoughts shared with friends on a private group blog before Facebook really took off, and even after that really. It will a useful place to look if my descendants want to know what my college friends and I were like in the mid-to-late aughts (provided they know my blogspot password).

Yeah, I was doing the same thing on a discussion board somebody else started, with a really fun group of people, though it was mainly about TV and film. Just fell apart over time, and it’s all gone now. Only ever met two of them in reality, still occasionally see one who lives nearby.

The thing about a review blog is that discussions can’t happen without a few people who have read the books. It’s hard to find people who have read a whole lot of the same books as you–online or off. Sure, if you’re into Harry Potter, Fire & Ice, like that, no trick to it at all, abbracadabra, discussion group. I’m not into that.

And I don’t know that even something as intense as the Parker novels could hold me for this long, all by itself. Westlake had layers and layers to him. I’ve got a few layers myself. My original idea was to do a blog called “Stark Outlines” (I even had a trial page set up on blogspot, with a photo of a chalk body outline in a library). But it wasn’t enough. I knew it wasn’t enough.

What I didn’t know was if I could get more than the occasional “Hey, great blog, thanks for the review, I love Westlake!”

If you or Mike or a few others here ever need somebody killed…..

😐

…yeah, I’ll give you a call. Oh, wait. Do you have a Handy Mckay?

I had very similar thoughts, back when it looked like violentworldofparker wasn’t going to be updated (and even when it was, it’s not like Trent was writing in-depth reviews). Then I found this blog and realized it was no longer necessary.

I still may do it for Barney Miller, but I suspect most of the comments will be along the lines of “Shepherd Book once played a cop?”

I hate that show. Okay, I hate people who love that show to an irrational degree, use the word ‘shiny’ in every other sentence, keep talking about shindigs, and offer to send you the DVD set when you critique it online. But at least it gave Ron Glass a few decent paychecks towards the end of his life. He deserved so much more. If you ever do that Barney blog, I’m there.

I feel like if I hadn’t done this, somebody else would have, perhaps not so verbosely. There were multiple predecessors, and I’ve tried to acknowledge all of them I could find. And once I’m done (if I ever am), I hope somebody else picks up where I left off.

Nobody thought much about Trollope for about a century after his death. Now everything he ever wrote is in print, and there’s a society devoted to his memory.

We wouldn’t remember Shakespeare at all if not for a few buddies putting that folio together.

You do what you can, and posterity does the rest.

I am up for a Barney Miller blog too.

Me too!

btw, that was a nice self-deprecating joke right before the the Columbus Day wishes. You had me indeed, because truth be told, I’m hoping we can stretch out the last three for as long as possible. I’m going to miss this place.

What!? What have you heard? It’s North Korea, isn’t it? 😮

I’m taking a break once I get that last canonical review in, but I’ve got more to say afterwards. And much more to read before I can get to this project I’ve had in mind a while now. Still not nearly enough context. The more I know, the more I know how much I don’t know. Y’know?

😉

Oh, I know.

It occurs to me that the Original 16 also ends with a triptych of sorts, but with that one’s middle panel having more of an anthology feel. (Maybe you’ve already made this point.) I wonder of some part of Westlake’s brain sensed the ending coming (twice) and (twice) crafted a three-book structure to mirror and comment upon the opening three books in the series. The final confrontation with mob in the third triptych strips away the last of the romance, doesn’t it? But we’ll talk more about that two (or three) books from now.

Less obvious there (and you can’t very well say that Plunder Squad represents a calm interlude between two storms), but yeah, you could call it that (and the center panel actually looks at the art world). You combine that with the first three novels, and you’ve got a Triplet of Triptychs.

Dirty Money is going to be a problem. Particularly since I intend to do it in one (probably very long) instalment. Poses more questions than it answers.

But look at it this way. We’ve still got this month.

I think.

Sandra Loscalzo’s (literal) turnaround reminds me of Franki Faran gradually realizing that he should probably be rooting for the heisters. Maybe not so dramatic a team-switch, but Parker has a way of making you realize that your best interests align with his.

I don’t think Sandra really has a team, in her mind. Neither does Parker, good a captain as he can be. They’re both free agents at heart, which is why they’re going to have one of the most interesting tete-a-tetes of the series, as it comes to an end.

Parker may not be a one-off, after all. I think that’s the point of Sandra.

I’m disappointed that Reversa doesn’t ask Parker some landscape design questions. He’s a good improviser, but it’s a subject I’m sure he knows nothing about.

She probably knows less than Parker (she’s the kind of cop who is a cop 24/7/365, as we learn in our brief glimpse of her dinner date), so that doesn’t work.

The mere fact that he knows there is such a thing as a landscape architect suggests he does know something about it. Maybe he’s researched it as a potential cover story, or an excuse for being found near some rich person’s house.

Reversa is whip smart, but let’s remember, she’s still an organization woman (as opposed to Loscalzo, who is anything but). She does everything by the book. Her instincts are screaming at her to cuff this guy (at which point the guy’s quite possibly going to chop her lovely neck with a huge veiny hand), but she’s got established protocol to follow, and we want her to do that, don’t we? That’s what a professional cop does.

An unprofessional cop isn’t even going to notice Parker, because he’s not black, doesn’t speak with a foreign accent, name doesn’t end in a vowel, and he drives a Lexus. The Cloak of Invisibility works just fine, most of the time. That’s why Parker uses it. He knows us pretty well by now. But there’s always more to learn, which is what the next book is about.

The end of this book disappointed me. Parker stops for a meal instead of at least getting out of the state? Western Massachusetts is not a large place – he could have been in NY in an hour from anywhere. The NY-MA border is mostly a long mountain ridge with few crossings. Getting across the state line should have been priority 1.

I’ve spent little time in MA, all of that in and around Boston, so can’t speak to geography, but ‘long mountain ridge with few crossings’ says something to me about how lucky he’d be to drive across that state line undetected. The state cops could cover every possible exit point.

I’ve mentioned Parker’s strange luck a few times–how even his ill fortune ends up working out to his advantage. If he’d kept on a few more miles past that diner he stopped at, he’d have hit the mother of all roadblocks–and going by what happened with the troopers who were checking out the car, his ID wouldn’t have held up that time. The TV at the diner was a good way for him to learn what he was up against.

The net’s tightening faster than he’s used to. He gets into New York on foot, but you know, New York is not Canada, and you don’t escape an armored car robbery rap by crossing a state line. He needed to cross several. And he needed new ID. And he needed to eat, as the narrator tells us–they didn’t have groceries stashed at the church.

This is where I’d aim my nitpicker (we all got one). What’s the point of a hideout if you’re not, you know, hiding out? The heat’s not going to die down in a day. Either they should be prepped to stay there a good while, groceries, bed rolls, etc (the helicopters make that problematic, since they need to have cars there), or they should have figured from the start on stashing the cash and running.

Of course, it’s really Dalesia’s plan, but Parker signed off on it.

I’ve mentioned how this book is an update on The Man With the Getaway Face–maybe the smoothest simplest heist Parker ever pulled (since the major wrinkle for Parker in that one doesn’t center around the job itself, sorry Alma).

The beauty of that plan is that New York and New Jersey aren’t on very good speaking terms (still true), and they can take a ferry over the state line, and there’s no damn computers worth talking about. Crossing into the most crowded metropolitan area in America, where anyone can disappear. I don’t know if it would have really worked that way there in the early 60’s–and I grew up in that part of New Jersey. But it’s plausible. Made more so by the fact that the other storyline keeps us distracted.

They have to get back to the factory. They have to get the cash out of the armored car. They could have tried splitting it up there, then each man for himself. But the cash is new, easily traced (they could never spend it in its current form), and they’ve activated a system designed to stop terror cells. Parker’s already been made by a state cop, and he doesn’t have a back-up ID. I don’t see any way to make it work as planned–no matter what the plan was.

And in fact, Westlake doesn’t want it to work, not yet. He’s not ready for Parker to get home safe again. He’s got a point to make and the point is that Parker can’t roll the same way he used to back in the 60’s.

You want realism? The realistic thing to do would have been not to pull the heist, or for Parker to end up dead or jailed. There’s enough of the romantic left in Stark that he’s not going to allow that. Not yet, and as matters worked out, not ever.

I agree the book’s got problems–as one book. But if it’s really the first third of what became a much longer book–which isn’t how it was published–then it’s a different ballgame. The point is to herd Parker into a place he can’t easily get out of. So that we can learn something about him–and about us. And all the while, he’s learning too. The third book is him looking for ways to defeat this new regime, and what we never find out is whether he’s pulled it out, or just boxed himself in. We’ll be talking about that soon enough.

I should have been clearer – before going to the diner his ID had held up through a roadblock so he should have kept going instead of eating. Once in NY he would have found himself on Route 22, which goes from the Bronx to Quebec, never more then a couple miles from the state line. Of course, that would not be as interesting as winding up in the fictional Pooley NY.

I always obsess about the geography of the last three books because I lived in Dutchess County for 59 years, spent a of of time in Columbia, Litchfield and Berkshire Counties, and still drive down Rte 22 from Vermont fairly often to visit friends and relatives.

You were clear enough, but maybe I wasn’t. His ID had held up through several early roadblocks (remember that roadblocks slow everybody down, much longer drive than usual to the NY line), but the system was catching up with him. He doesn’t know the back roads well enough to try that way.

By the time he’s reached the diner, they’ve already made the connection–because, after all, he showed that same ID to Reversa, days before. What they didn’t have was the license number of the Dodge he’s driving, now that he’s ditched the Lexus. But once he’s shown that ID to the law while driving the Dodge, it won’t take long to link the two. Because computers.

If they already had troopers checking parking lots for the Dodge (and they’d have a lot of parking lots to check), most likely they’d have him made at the next roadblock without even asking for ID. They’d just come at him weapons drawn, loudspeakers blaring.

He was going to hit at least one more roadblock before he crossed the state line–and since we learn from Tom Lindahl that there are roadblocks in New York as well, they’d probably have Route 22 covered (MA and Upstate NY talk to each other just fine). And it’s a long long drive back to NJ. He is going to have to rest and eat at some point, and they are going to keep looking for that Dodge. If he drives it close enough to Colliver Pond, he’s given away the home base.

He needs new ID, and a new car, to make it work. So if he hadn’t stopped to eat–and he’s not a robot, he hasn’t eaten since the previous night–hard to see how he’d have made it. And up at the top of the hill there’s a new job waiting for him. His strange luck.

A key passage for this side-discussion:

The TV in the diner is showing the news from an Albany station, and of course he’s only a short climb from the New York border as we learn in the next book, so he’s almost there. He’s made it through several roadblocks, not one. He agrees with you about leaving MA ASAP, and I agree with you that he wouldn’t die of hunger if he drove a little further.

So why doesn’t he? Maybe just because it suits the needs of the story for him to stop there. Good bet Westlake wrote this and Ask the Parrot close together. He already knows he’s taking Parker into New York, but not by car.

But also, because Parker’s instincts might have told him to wait a bit before hitting the state line–sniff the air before proceeding. Find out just how bad the situation is. And if he hadn’t done that, I really don’t think he’d have gotten through the next roadblock. There just wasn’t enough time. The next roadblock would be the last roadblock.

It is mentioned that he’s traveling by secondary roads–to try and get past roadblocks, but they’re being really thorough, and as a result, he’s making much slower progress than he expected.

You know the territory much better than me, goes without saying. Westlake was raised upstate, I think we have to concede he’s on home ground himself here. I was raised in Monmouth County NJ, so you don’t need to tell me about Rt. 22. I did make it as far west as the Syracuse Airport this one time–detour after a trip to the Adirondacks. It’s a whole lot of driving to get back to the NY metro area, which Parker exists on the far periphery of in Sussex county.

I’ll also point out that in Backflash–which probably takes place some years before this book–Parker is so exhausted from lack of food and rest after hours of driving that he gets hit from behind, knocked out. He may not be human, but it’s still a human body he’s in. And that body is aging. We all know that territory.

If he lets himself get too frazzled, he’s going to make some bad mistakes at key moments. And he need to reconnoiter as well as eat (and, you know, what comes along with eating and drinking). So on the whole, I think the diner makes sense.

But now (editing, with a Delorme in front of me)–are we talking Page 53–or 67?

Makes a bit of a difference.

Page 67 would not be good – either Rte 2 or Rte 43 are bottlenecks and could be shut down easily. Further south on page 53 there are a couple local roads that might not be blocked, but I bet Parker does not have a Delorme handy.

Now if he headed north into Vermont he probably would be clear as there are very few police here. Ditch the car in the woods, chill for a few days, then take Amtrak back to Penn station and NJ Transit/Metro North to Port Jervis. But Parker has probably not been on a train ever – too easy to be trapped.

You know, this could be a whole new blog–“Criminal Byways”? “Grand Theft Positioning System”? I’ll work on it.

We should recognize that the very rapid response threw the entire escape plan into a cocked hat, and he’s got to improvise. That’s one of the points of the book, that things have changed, the old methods don’t work so well, so we can’t kick too much about it. If he’d known, he’d have had some of those little roads picked out in advance, as a back-up.

My question is, regardless of whether Page 53 or 67 makes more sense from the standpoint of escape–which page is he actually on? He was in the far northwestern corner of MA. After things fall apart, he’s heading west as much as possible. Here’s the money quote–obviously the town with the nice little bank that should be robbed is no more real than Copper Canyon, Fun Island, or Cockaigne.

And we’re told there are ski slopes nearby. Sounds like 67 to me. But the lower half of the page. You’re probably right that Vermont’s the better pick in terms of a getaway, but the wolf in him wants to get back to his mate. New York’s the faster route to Claire, and he probably doesn’t know Vermont at all–I mean, what’s he going to do there, rob Ben & Jerry? 🙂

This also explains why people are watching an Albany TV station at the diner. Albany would be this looming presence there.

What I’m having a harder time with is Syracuse, mentioned in the next book as if it’s fairly nearby. It’s halfway across the state–the long part of the state, and you know how long that is.

To be fair, Lindahl says the track is ‘down towards Syracuse,’ (so just another way of saying northwest?) and you expect Westlake to fudge the exact location as much as possible, since there is no such track, and I see no evidence there ever was.

It’s about an hour to the track from Pooley, which is only a few minutes away from the MA state line. And they keep hitting road blocks when they drive there. Incidentally, I’ve never hit a police roadblock in my life, in any state–have you?

I will be very interested in your geographic input on the next book. And any other input you might have, but this criminal atlas thing intrigues me.

Parker’s usual plan is to stay near the scene of the crime (not too near) for a few days, until the heat dies down. So it’s odd that they don’t bring enough food to do that. Though it might not have mattered, because they heat doesn’t seem to be dying down.

This is one of those jobs where Parker is mainly just a troubleshooter and enforcer–not a planner. Elaine is the finger, Jake finds the factory, Dalesia picks the spot for the ambush and the hideout. They’re near a state line, so it makes sense to get out of the state entirely, particularly since even though it’s rural Massachusetts, it’s still Massachusetts. The best hideouts are either in a large anonymous town, or out in the middle of nowhere with few prying eyes. This is neither.

Parker doesn’t see any obvious problems with the plan, but it’s not his plan. And after his experiences in Palm Beach, he’s hardly going to think a hideout is the answer to every law-related problem.

When Alan Cavalier adapted The Score into Mise a Sac, he dispensed with the hideout altogether. Who’d believe it? Rural France is still France. (It works in the book, because the area around Copper Canyon is so vast and sparsely populated.) After a job like that, the whole countryside will be looking for them. Every abandoned farmhouse is known (or turned into somebody’s country home, as in Jimmy the Kid). The plan is to get back to the nearest large city, Lyons, and disappear there.

At some point, some smart smart trooper or FBI agent would have said “Hey, let’s look in that old abandoned church.” Or irate neighbors would have complained about these strange cars parked outside their houses for days. The houses we’re told are right across from the church. It’s not isolated enough. Only good for a short-term place to hole up. (You have to wonder if they should have made the derelict factory the hideout, since they have to go back there anyway, but then you lose the joke about the hymnals).

Shouldn’t Parker have seen the less obvious problems? Maybe he did, but the hunting impulse was too strong, and the opportunities too few. And since he wasn’t required as a planner this time, he didn’t micromanage. Once he really gets his teeth into a job, he tends to stay with it, come what may. One of the beauties of Plunder Squad is that we get to see him reject several jobs in the early planning stages, before he settles on one–and it doesn’t work out at all.

I can trot out all kinds of excuses here, point out that it’s not really inconsistent with that we’ve seen, but the job’s still shaky, I think we can all agree on that. One of the problems with doing early-to-mid 20th century style heist stories in the 21st century. Dortmunder is having the same problem, but Westlake is going to present a solution in the final book. Westlake gives the much more challenging final score to Parker–because Parker can take it. Dortmunder may actually be the better planner, but Parker is the ultimate troubleshooter.

There is a racetrack in Vernon NY which is west of Utica (page 76 in Delorme). No one in his right mind would drive there from the Mass. border. I think Westlake relocated Saratoga farther west, as that drive could possibly be done in an hour and a half or so.

I have never been stopped at a roadblock and I have never watched TV news in a diner. I don’t think I have ever seen a TV in a diner. I did see Andy Rooney in the West Taghkanic Diner once.

“Did ya ever notice that in the Parker novels, they close down all the roads after a heist, make everybody show their ID, but in real life that never happens, because people would rather the criminals got away than to put up with the extra traffic, and there’d be a ton of angry letters to state assemblymen? Why is that? Oh wait, I just answered my own question.”

Even the Final Eight–even The Triptych–very retro. All the books in the series are, and Parker most of all–when Westlake describes him as “Dillinger mythologized into a machine,” he’s reminding us that much as we love these stories, and much as armed robberies still happen every day, the golden age of bank robbery was over before most of us were born. To read these books, you do have to suspend disbelief, and it’s a mark of Westake’s greatness as a writer (in or out of Stark mode) that we do, most of the time.

Saratoga is too big, too busy. No way anybody would buy a former employee being able to stroll in and out of there on a whim late at night, and just two guards watching the whole place. Gro-More’s only open twice a year, for a grand total of forty-eight days. They have ‘meets.’ A relic of the past–which to be sure, is precisely what horse-racing represents, but they keep trying to rationalize it.

They’re talking about trying to set things up so they can have people come in and gamble on races going on elsewhere the rest of the year. No mention of other kinds of gambling–well, New York only approved that in 2001, and it took a few more years for them to get set up. And once that happened, there’d be huge security–see the problem? Only because you’re looking for it. So don’t look for it.

Hell, we don’t even find out what kind of racing they do–standardbred or thoroughbred? I’d assume the former, but it’s never mentioned. And that’s because Parker doesn’t care.

I suppose there must be diners with TV’s (certain been a lot of them on TV, sitcoms and such), and they might turn on the news if there was a really exciting local news story. A bar that serves food might have made more sense. Particularly since there’s already been a bunch of diners in the book. Call it a motif. I’ll definitely be looking for a TV in the next few diners I eat at–there was one at a greasy spoon coffee shop at 231st & Broadway we ate at recently, which is kind of a diner. But mainly you go to a diner to tune out, not in.

(I wish there were more bars with no TV. The one we’ve got in the nabe is tiny, and full of young people. They do have a phonograph and lots of old vinyl LP’s. Speaking of retro.)

Oh, and I’ve been around Utica. Drove up there with an English birder in a rented car this one time, to look for a Yellow-billed Loon. Or as the Limey called it, a ‘diver.’ It’s a LOON, bucko! And so are we, for spending all those hours in a compact car, to find a bird. But we found it.

Westlake never lost his ability to fully imagine a place with a long history and backstory. Lindahl and Thiemann’s history lesson may lean towards expositional, with their talk of the iron mined for one war and the train tracks pulled up for another, but I never for a moment doubt this place. I can picture it all: the woods, the old roads, the abandoned railroad station nestled among the trees and scrub, offering temporary shelter to the hunters and the homeless. Westlake was always interested in how little corners of the world worked, and how those corners came to be the way they are. His backstories (for people and places) were always superb, right up until the end.

I’m getting close to the end now, and it’s just as good as I remembered, maybe better. The Last Masterpiece. And the two books that bookend it, for all their flaws, are somehow the perfect accompaniment for it.

And there’s even a little missive on forgiving readers (got it typed out for Part 2 of my review). Forgive the author’s fictional trespasses against logic and continuity–as we hope to be forgiven for our own very real ones–which are far more dangerous.

There’s also a thematic continuity between NRF and ATP I didn’t see the first time I read them. Not sure if it continues into DM.

In both books, Parker is approached in relation to somebody who wants to rob a place s(he) feels a deep sense of connection to, and an equally deep sense of alienation and betrayal. Both dream of somehow escaping their unsatisfactory lives with the money from their share, but the real motivation is righting a wrong. Something Parker can understand, but he also understands that such feelings can make you do things that don’t make sense.

These two fingers are very different from each other. And only one of them gets to spend a significant amount of time with Parker.

There’s no heist in the final book, and no finger. To the extent there are thematic continuities, it’s because the final book ties up all the loose ends from the previous two–but it also introduces some new arcs that we’ll have to tie up ourselves.

It’s a theme Westlake returned to more than once, with Lindahl and Elaine Langen and Edgars and Richard Curtis and (to a lesser extent) to Parker himself in The Outfit and Butcher’s Moon. Lesser extent because Parker doesn’t feel a connection to those institutions, but he shares with the others a deep sense of betrayal, and the need to make his enemies suffer losses (via robbery and other mayhem) to offset that betrayal.

It’s interesting that Parker’s only full-fledged vendetta of the Final Eight was Flashfire. Which you know I think was a failure, if an interesting one. It feels like an overreaction, which I think is somewhat intentional–Westlake trying to bring back the old Parker of The Hunter, The Outfit, The Seventh, Butcher’s Moon. But does he ever really feel angry in that book? Going through the motions–the only things he does in that book I believe in are the string of small robberies he does to bankroll his revenge against the Gaudy Trio. And there’s no special passion in those jobs.

Now of course he has to kill George Liss in Comeback, but Ed and Brenda are in full agreement with that–it’s a pragmatic necessity, even if Parker is doing it for reasons that aren’t entirely pragmatic. And Liss never leaves town, keeps coming back for the loot, and to finish his partners off, so it doesn’t have the same Quixotic feel as Parker’s war with The Outfit, George Uhl, and etc.

Firebreak, he’s thinking about killing Larry Lloyd for compromising his identity online, but Lloyd’s increasing confidence and self-understanding convince him it’s not necessary, the impulse gets switched off. He has to come after Brock and Rosenstein, before they can come at him again, and once more it works out differently than you’d expect. Parker had no beef with them until they picked a fight with him. Not a vendetta, in either case.

And there’s somebody he has to kill in Dirty Money, but that again has thorougly practical reasons behind it. The person he’s after hasn’t violated any of Parker’s unwritten laws. He’s just become–inconvenient. A problem that has to be addressed, nothing more.

Parker is much more consistently rational in the Final Eight. He’s mellowed in that respect, I guess you could say, but I’d say he’s stabilized, matured. He’s maybe something of an adolescent wolf in the earlier books, testing his limits, developing coping skills–as his creator was doing. He’s not angry anymore. He’s accepted the world as it is, humans as they are. There’s nothing he can do about any of that, except to survive it, and maybe sometimes exploit it as a weakness.

So it creates a somewhat different dynamic between him and the various people he works with in the Final Eight who do have vendettas, who are still very angry at the way things are. He can understand it, but he doesn’t quite share it anymore.

What would it take to revive that old feeling in him? Maybe if somebody abducted or murdered Claire. Would Stark have ever gone there, you think?

I’m starting to rethink my endgame, with regards to the main run of reviews.

The idea was that I’d review all the remaining Dortmunders but the last one, ignoring publication order for once, then do the final three Starks together. I don’t repent of that, don’t see how the books I’m reviewing now can be understood except as a tripartite narrative structure.

But out of a sense of divided loyalty, I thought I’d publish one-part reviews for Dirty Money and Get Real at the same time–and these would be, respectively, the 200th and 201st posts. I’m not sure that’s practical, and furthermore, I’m not sure I can cover Ask The Parrot in just two parts, in spite of its relative brevity–so many layers to work through. Dirty Money might require two. Get Real I’m pretty sure I could do in one (long) post. So I’d be finishing off the Westlake novel reviews with post #203. The decimal system is overrated, anyway.

So Parker gets more virtual ink, which matches up with the larger amount of actual ink he got. Dortmunder gets the last word, as he did in the books. That seems fair enough to me. Make it so.

(I’m kind of dreading the end myself, but a true literary review never stops parsing the material already covered, and there are some kindred spirits of Mr. Westlake I want to discuss here as well. I could provide a reading list, if you like.)

Yes, please.

I’ll post a list in the near future. I’m sure some of you will have read some of those books. I’m equally sure some of my regulars won’t take to all of these other authors, who can be off-putting, disturbing, perhaps intentionally so. Maybe I’ll lose some regulars, pick up some new ones. But without somebody to discuss the books with, I’m just talking to myself.

It’s not like I’m going to do for these surly scribes what I did for Westlake–for me, at least, that was a one-off. But I do feel that he and they were connected, in ways that could never be explained. But perhaps illustrated.

Quite sure now that Dirty Money will require three as well. So it’s going to be a Nontet on the Triptych.

I do, actually. The Claire-in-jeopardy plot was well worn by the end of the first 16, so I can see why Westlake avoided it in the final eight. But there were signs that Colliver Pond may not be a safe haven for much longer. For one thing, people keep finding it because of Parker’s damned phone number. (Seriously, Parker: burner phones; look into them.) For another, there’s a subtle thread woven through the final eight in which Claire keeps getting drawn back into Parker’s world, helping him with research in Backflash and Firebreak, accompanying him to McWhitney’s bar in Dirty Money, drawing the FBI’s attention (in Dirty Money again), and generally taking more of an interest in Parker’s other life. We’ve seen Claire get kidnapped before, so Westlake probably wouldn’t have revisited that scenario. But it’s interesting to think about how Parker would have responded to Claire getting arrested. And it’s horrific to think of his reaction if she were to be murdered. Another couple of books, and we may have found out.

It’s going to look bad if Claire doesn’t have a landline (or, as they get more established, a regular cellphone). Parker is suspicious of anything new–and there are innumerable ways that cellphones and the internet can compromise you.