Publishing is the only industry I can think of where most of the employees spend most of their time stating with great self-assurance that they don’t know how to do their jobs. “I don’t know how to sell this,” they complain, frowning as though it’s your fault. “I don’t know how to package this. I don’t know where the market is for this book. I don’t know how we’re going to draw attention to this.” In most other occupations, people try to hide their incompetence; only in publishing is it flaunted as though it were the chief qualification for the job.

A Fictional Character in a Fictional Work that is in no way meant to represent the Real World.

Anyway, I decided to try to describe my experience in publishing without describing my experiences, if you follow my drift. Not a roman a clef, that boring substitute for invention. No thinly disguised actual people, no undigested anecdotes of true happenings. What I wanted to write was a novel, which is a parallel universe as real as our own but with different incidents and a different cast list. So I didn’t include the fellow who said to me “I’m not your real editor, so I don’t have to get to know you.” I didn’t include the friend’s publisher who forgot to send out review copies; nor the publisher who habitually describes books in next season’s catalog that haven’t been written yet (as a result of which, a novel that was never written and never published nevertheless got an admiring magazine review); nor the publisher who reneged on a contract because he wanted to save my career, which would be ruined if I permitted him or anyone else to publish a novel of mine called Adios, Scheherazade, which was later brought out by someone else and hasn’t ruined my career in the 15 years since, but I suppose still might. Nor did I include the editor whose secretary hated him because she knew she was younger, faster, smarter, thinner, and prettier than he was, and he was in her way.

No, I invented my own parallel universe, so none of those people or incidents are in it, so A Likely Story isn’t true. But it’s true.

From an article in Writer’s Digest, by Donald E. Westlake

This book garnered Westlake a rare rave review in the New York Times for one of his non-criminal efforts–but somehow I don’t think it gave him much pleasure to have the well-meaning Marilyn Stasio (who would soon take over the mystery fiction beat there from Newgate Callendar, who had taken over from Anthony Boucher, Westlake’s great critical champion) tell the world in what was supposed to be an inducement to buy and read the book that it had been turned down by one confused-looking publisher after another, and that it fell to Westlake’s compatriot Otto Penzler to get it out there. Westlake told the same story himself later on, mind you, but with a lot more pizzazz, and after the book was already safely in paperback.

(Also, I would think he winced a bit when he saw that Ms. Stasio, no doubt contending with multiple deadlines, had tossed off her review so quickly that she’d rendered the title of his book as “An Unlikely Story” at the conclusion of the piece, having given the correct title to start with. And no editor caught that? I bet this never happens to John Irving.)

Mr. Penzler went above and beyond the call of duty here–that copy in the distinguished looking protective sleeve you see at the top left of this review is part of a limited deluxe printing Penzler Books put out, signed by the author, and it was on sale for $14.95 at the site I filched this image from. O tempora, o mores.

Penzler would be amply repaid for his loyalty and professionalism in the years to come with nineteen more Westlake books and seven Richard Starks for The Mysterious Press (twenty-six novels, two anthologies), many of which were instant classics, and none of which were anywhere near as hard to pigeonhole (or market) as this one. This book had its admirers then, as it does now, but the lack of even an electronic edition attests to the elite nature of that fanbase.

And to attest further to that elitism, I provide to the right of that limited edition copy, the title page of a rather delightful 1987 article Westlake did for Writer’s Digest, which seems to have come out around the time the paperback edition of A Likely Story showed up, and I finally figured out how to read it just now (The Official Westlake Blog could have made reading that scan a bit easier, but then again it could have provided no scan at all, so head over there and get the rest of it, post haste–it prints out fairly well, but you’ll have to download both pages individually first).

It’s always gratifying to me when my guesses regarding the origins of a book I’m reviewing prove out, and I can certainly feel for Mr. Penzler’s situation when, on the verge of landing one of the world’s great mystery writers for his start-up mystery publishing house, that writer told him his next book would not be a mystery, but rather a comedy about the mind-boggling incompetence of the publishing industry and the woes of ‘serial polygamy’, that had been vehemently rejected by multiple publishers already.

His mettle was being tested here, you see–and he cleared that high hurdle with room to spare by saying “That’s okay, I’ll publish it anyway, because your next book will be a mystery.” It was actually a sort of multicultural comedy of errors set in Central America– the one after that ranks among the greatest of all Dortmunder novels, and the Dortmunders aren’t really mysteries either in any strict sense, but let’s emulate the broadminded Mr. Penzler, and eschew the foul practice of nitpicking–close enough.

He actually had to create the Penzler Books imprint out of thin air to accommodate this novel, and it worked out pretty well for him–turns out a lot of people slotted as mystery writers sometimes want to write a non-mystery, and he subsequently added the scalps of Gregory (Fletch) McDonald and Patricia (do I have to say it?) Highsmith to his publisher’s belt. Don’t you love it when virtue is rewarded in fiction? As it hardly ever is in real life. Back to the synopsis.

Tom Diskant, journeyman nonfiction author, and aspiring anthologist, is still slaving away at his magnum opus, a ‘Christmas Book’ that happens to be about Christmas, full of artful stories and essays and visual representations of that holiday to end all holidays, from a virtual Who’s Who of Literature, Politics, Showbiz, and the Arts, circa the Mid-80’s. With an established publishing house behind him, he sends out a letter requesting submissions, to a wide variety of famous names. To wit (and in order of mention):

Edward Albee, Woody Allen, Isaac Asimov, Russell Baker, Ann Beattie, Helen Gurley Brown, William F. Buckley Jr., Leo Buscaglia, Truman Capote, Jimmy Carter, Francis Ford Coppola, Annie Dillard, E. L. Doctorow, Gerald Ford, William Goldman, John Irving, Stephen King, Jerzy Kosinski, Judith Krantz, Robert Ludlum, Norman Mailer, James A. Michener, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Richard Nixon, Joyce Carol Oates, Mario Puzo, Joan Rivers, Andy Rooney, Philip Roth, Carl Sagan, Isaac Bashevis Singer (what the hell), Steven Spielberg, Sylvester Stallone, Diana Trilling, John Updike, Gore Vidal, Kurt Vonnegut, Joseph Wambaugh, Tom Wolfe, Herman Wouk, Charles Addams, Richard Avedon, Jim Davis, Jules Feiffer, Edward Gorey, Robert Kliban, Jill Krementz, LeRoy Nieman, Charles Schulz, Andy Warhol, Arthur C. Clarke, Joan Didion, John Gregory Dunne, John Kenneth Galbraith, Garrison Keillor, Henry Kissinger, Jonathan Schell, Mickey Spillane, William Styron, Paul Theroux, Roddy McDowall, Helmut Newton, Francesco Scavullo, Gahan Wilson, Jamie Wyeth, Pauline Kael, John Leonard, Sam Shephard, John Simon, Calvin Trillin, Jasper Johns, David Levine, Roy Lichtenstein, Saul Steinberg, and Tomi Ungerer (backdated, see the opening quote from Part 1).

It really says something about our popular culture, such as it is, not to mention Mr. Westlake’s deadly accuracy as a satirist of same, that most of these are still names to conjure with today. There’s maybe half a dozen people on that list I hadn’t heard of before. Of course, I was in my 20’s during the 80’s–that helps.

He gets an unsolicited offer from Pia Zadora’s agent (not all 80’s icons held up over time), and Scott Meredith, being the agent for several of the writers who don’t want to contribute, keeps sending him cartons full of unsold material from his undiscovered clients. It’s hard to say whether he expects Tom to buy any of it, but the point is, he tried, and he can keep exacting fees from aspiring wordsmiths with a clear conscience, though the stories one hears about Mr. Meredith would tend to argue against his being burdened with such an outdated encumbrance.

Andy Warhol sends him a photo of an old Coca Cola tray with their classic version of Santa Claus (courtesy of McCann-Erickson, and would you believe I worked there too? I get around, I’m telling you). Mr. Warhol has, with his typical protean creativity, embellished this venerable pop cultural artifact with a few tasteful squiggles. Tom regretfully declines, then contacts Coca Cola’s PR department, and gets the rights to use the unembellished photo, gratis. Which, when you think about it, is the best possible homage he could pay to the genius of Warhol. Whose museum I visited once. What else can you do in Pittsburgh?

Gathering the material from which the book shall be shaped has gone better than he had dared hope (and stranger than he could have dreamed), and he knows he’s got the makings of the most brilliant and original coffee table book ever printed here, but to make the book happen, he needs two things–a publisher–and an editor. And he has been rather less fortunate with regards to those two grim necessities.

His original editor, the guy who originally bought the book, and was supposed to see it through to publication, has departed his former employer of Craig, Harry & Burke, to take a job with a pay-TV Company. Tom generously hopes that he will rot in hell, and if it’s Cinemax, that probably did happen. In the meantime, Tom has been stuck with replacement editor Vickie Douglas, who showed no interest in his book at all, until in a burst of sympathy over her terrible relationship with her mother, he kissed her, and one thing led to another (and another and another and another).

So now Vickie is full of enthusiasm for The Christmas Book, but that enthusiasm is contingent upon her enthusiasm for frequent illicit coitus with Tom. The fact that he is still legally married to one woman and openly living with another while shtupping his editor on the side merely adds further zest to the proceedings, as she sees it. He’s got to stick it out with her (so to speak) until the book is safely off to market.

His wife Mary continues to try to win him back, while his mistress Ginger gives him suspicious looks and insists that he maintain his usual high standard of performance in the bedroom. Tom starts to lose weight rapidly–hey, maybe Vickie was onto something with that Fuck Yourself Thin book she got from a retired hooker and repackaged under the title How a Better Sex Life Can Lead to a Thinner You. Except she was already thin, and after they’ve been at it a while, Tom begins to notice she’s putting on weight. Huh. More on that shortly.

Could Tom’s domestic and personal affairs get any more complicated (is a question no sane man would ever ask)? Ginger’s husband Lance, to whom she is still legally married as well, gets thrown out of his apartment by his girlfriend, and apparently finding affordable new digs in Manhattan wasn’t any easier in the 1980’s than it is today. He’s the father of her children–he’s contributing to the rent for the apartment she shares with Tom and her own children–can she just turn him away when he’s in need of a roof over his head? Tom devoutly believes she could, but is forced to concede that she won’t, and neither would he in her place (there really are no bad guys in this book at all–just bad publishers and bad relationships).

So Lance is now sleeping in the room Tom normally uses for his office, and he’s reduced to working on the book–and on his secret diary he is so generously sharing with us–in the small bedroom he shares with Ginger. Eventually he just says the hell with it, and accepts Mary’s far from selfless offer to use his old office at their old apartment, where she is in constant and extremely tempting proximity to him. Ginger is not happy with this situation. Tom is not happy with this situation. Mary’s fine with it.

Domestic complications abound, most of which keep drawing him back into the coils of a marriage he is trying to abandon–his 11 year old daughter Jennifer, a tough streetwise city girl, gets mugged, and needs to be reassured of her toughness and street wisdom (and indirectly that she’s not racist for having been scared of the two older black kids who robbed her). His son needs to do father-son stuff with his dad, go to ballgames and such, often with Ginger’s son coming along as well.

But he also has to deal with the fact that Ginger’s daughter Gretchen, who sees him much more regularly than her own father Lance, wants his approval and encouragement and love, even though he’s not particularly fond of her–he doesn’t dislike her, he’s trying to be nice, but does he have to act like he adores her? Both Ginger and Mary inform him that yes, he does in fact have to do just that. And he’s forced to acknowledge to himself, and to us, that he’s done a crappy job as surrogate father to her. (And maybe there’s just a wee touch of roman a clef there, but I wouldn’t know.)

We all have work lives and personal lives (these days, the latter may be almost entirely conducted via electronic impulses, but hopefully not). Balancing the two was never easy, but it’s become bizarrely comically difficult as our work selves become more and more divorced from our true selves, and may even begin to replace our true selves. And those of us who engaged in ‘serial polygamy’–that is to say, marrying, producing offspring, then separating from our spouses, but still trying to maintain a relationship with our abandoned offspring (which the law generally insists upon to some extent anyway), or failing that, our abandoned pets.

Westlake had two subjects in this book, as he details in that article for Writer’s Digest. But underneath, they’re the same subject–he wanted to create a protagonist who is in the grips of a great idea–the significance of Christmas in our yearly cycle of existence–but the people he needs to work with in order to bring this idea to fruition are hopelessly inadequate to the task, endlessly sabotaging him–even the creative people, the writers and artists he’s calling upon, are a preening passel of enfants terribles, squabbling over cash and copyright. But at least they’re giving him good work–they’re not the real problem. I think you’ve figured out by now where the real problems are coming from.

But then he goes home, to the results of serial polygamy, of abandoning one relationship and starting another with somebody who had done the same exact thing, each seeking some romantic ideal, but still obliged to cope with the variously appealing but equally needy results of human reproduction, and (this being New York City in the 1980’s), each having his or her own career to worry about, as well as children, as well as trying to find that ideal partnership, that perfect pairing of opposites that we see in movies and read about in books and never quite find in tangible reality, though certainly some get closer to it than others, which just adds to the overall sense of injustice, and leads to still more broken homes.

So Tom Diskant, split into many disharmonious parts by this life he’s chosen, tries as best he can to do justice to them all–to be a good nonfiction author and compiler of other authors, a good lover (to two different women), a good ex-husband to the wife he still has feelings for (and is still married to), and a good father–to his own children, and to children he had nothing to do with putting in this world.

And sometimes he pulls it off, and more often he doesn’t. But he wants to get it right, that’s the thing–he wants a career, he wants a family. His obsession with Christmas–and really, with every single holiday on the Gregorian calendar (he’s becoming something of an expert on the subject)–it all comes back to his desire to find that perfect family unit, that sense of belonging to something eternal and pure. That’s what Christmas is really about, he realizes–not the birth of Jesus (which didn’t even happen anywhere near that date), but the birth of The Holy Family. The ideal we all strive for and never reach (and presumably neither did the actual Holy Family).

His only published novel was about his ideal childhood in Vermont (ideal as he remembered it, anyway), the friends and family who formed his sense of himself, the happy Christmases every child treasures–and airbrushes into some Currier&Ives postcard of the mind as he or she grows older and life gets more complicated. Maybe he failed as a writer of fiction because he didn’t realize that the best fiction has to be about precisely those complexities. Unless you’re writing children’s books. And the best of those are deceptively complex themselves.

But the mission statement here is laughter–at ourselves. So Westlake piles complication upon complication–summer in New York City is a hellish thing at times, and those who can afford an escape route try their level best to get away from it–for hardworking professionals who can’t get too far from the office for too long, one such escape route is Fire Island (which factored heavily in Two Much, and will be seen in a much later novel as well). Tom has gotten enough of his advance for The Christmas Book that he can just barely afford to take himself, Ginger, and the kids (all the kids) to stay there for a few blissful weeks in a tranquil carless beachfront environment ten degrees cooler than the sweltering city. Get away from it all. Or so he thinks.

Mary insists she has to come as well–there’s no money for her to go off on a separate holiday–and then Vickie protests she needs to spend time there, to go over the galley proofs of the book (among other things). So in no time at all, the increasingly horrified Tom finds himself sharing the same domicile with his mistress, his girlfriend, and his wife–three smart sexy women in bikinis, lounging in the sun, each with very specific designs upon him, and it may sound like a salacious male fantasy, and that it most certainly is, but rest assured, it’s a fantasy with teeth.

I was seated on the back deck a little while ago, reading the Sunday Times Magazine, and then I looked around at the three other people also on the deck, also reading sections of the Times, and I found myself thinking: I have been to bed with all three of these women.

The thought did not make me feel like a harem master or anything particularly macho. In fact, all I felt at that moment was vaguely scared. Three women in bikinis in the sunshine, reading Travel and Arts and Leisure and The Week in Review. If they were suddenly to rise and turn on me, they could tear me to shreds. Sitting there, looking at them, thinking about it, I could find no very good reason why they wouldn’t rise and turn on me.

Art Dodge, the blithely bed-hopping twin-fucking anti-hero of Two Much (a much easier book to sell to a publisher than this one–or a film studio, for that matter), would relish this erotic tableau–at least until the bill came due–but somehow Tom Diskant can’t just relax and enjoy the view. He retreats to his makeshift office in the rented beach house, and works on his book, while the girls work on their tans.

Before long, Vickie will demand sexual favors from him while Ginger is out of the house, then Ginger will demand still more sexual favors once she’s back in the house, and all the while Mary will go on telling him, as provocatively as she knows how (and that’s pretty damned provocative), about all these men she meets who keep coming on to her in various disgusting yet strangely fascinating ways because they can tell she doesn’t have a husband to protect her. Tom is very much of the opinion that she’s not the one who needs protecting here.

And they still all somehow end up having a great summer there on the island (the kids most of all, who just ignore the adult-themed goings on because they have their own personal dramas, far more interesting and important and irrelevant to Tom’s narrative)–even Lance gets into the act–but all vacation idylls must end, and then one has to deal with the grim realities of the workplace.

And those realities are grim indeed–Vickie is pregnant. That’s why she was putting on weight. An innate design flaw to the whole Fuck Yourself Thin weight loss plan. She flatly insists it’s not Tom’s, so that’s something–my personal opinion, not quite corroborated in the book, is that she’s pregnant by Tom, and simply isn’t crazy enough to exert a claim on a man of limited means and dubious prospects she knows to be multiply claimed already–it was just a fun fling for her, no deeper feelings.

Now I would have thought the 80’s were modern enough, at least in Manhattan, for a successful career gal who got knocked up out of wedlock to go on working for at least a while, but whether it’s the innate conservatism of the publishing industry, or Vickie’s now urgent need to do what her mother has been telling her to do for years and find a husband (which she does with admirable alacrity, as Tom finds out later), she quits her job as editor. The Christmas Book is now doubly orphaned. And it turns out Vickie was very far from being the editorial worst-case scenario.

Tom’s third and final cross to bear is Dewey Heffernan, 20’s, tall, gangly, earnest, and intensely stupid. He got this job through a cousin at Random House, who made damn sure Dewey would not be employed anywhere near Random House. Turns out the cousin had contacts at the Solenex Corporation (which has figured in earlier Westlake comedies, as has the Tre Mafiosi restaurant Tom lunches at with Dewey), which owns, among many other things, Craig, Harry & Burke.

Dewey has never worked as an editor before, or indeed any position of the slightest significance. This is his very first job in publishing–editing Tom’s book. This is starting at the bottom? Whatever happened to the mail room? Worked out fine for Robert Morse. Well, he should at least be malleable, right? Open to suggestion? Tabula Rasa? Unfortunately, his mind is already packed to the rafters with bad ideas, leaving no room at all for any good ones. Dewey sees himself as a voice of his generation. He probably is. That would explain a lot.

“Pictures,” he said. “Color. Youth appeal. You see what I mean?”

“Yes, I do,” I said.

“We’ve got to attract that youth audience, Tom,” he told me. “Those are the readers of the future!”

“Undoubtedly true.”

“They see things differently, Tom! They’re used to, they’re used to, video screens. Display! Computer programs! Rock and roll!”

“Ah hah.”

“If we want youth to be interested in us, Tom,” he said, leaning close over his forearms, eyes and nostrils staring impassionedly at me, “we have to be interested in what interests youth.”

“Interesting,” I said, as our waiter brought our drinks.

Tom figures the book is already done, the checks have been mailed, the publishing house is committed, the release date is set in stone for just before Christmas–what the hell. He just has to humor this twit a while, he can’t do any real harm.

Unfortunately the twit has no sense of humor–or of the absurd. In the midst of their increasingly drunken lunchtime meeting, Tom just sitting there nodding vacantly with a glassy eyed expression, making vaguely compliant noises, he got the impression Tom was agreeing to let him commission an entirely new work of art, appealing to those hot happening young hipsters who so love to buy large expensive books about Christmas to place on their coffee tables.

And does he at least get Robert Crumb, Art Spiegelman, or some equivalent Underground Comix god or goddess? Of course not. He gets this guy named Korban, who does a lot of stuff for Heavy Metal. And he didn’t talk to anybody–he just made the offer. On company stationary. And received the goods. For which payment must now be made. Even though it was never approved by anyone. Other than Dewey. Who has no authority to approve jack spit. Oh shit.

Now Westlake went out of his way to say at the start of this book that all the very real public figures he refers to in it should not think that he is genuinely depicting them–he is merely having fun with their public image, the idea people have of them. Well and good, but thing is, much as he may approve more of some of these people than others (most he simply admired from afar, a few he was on warm personal and professional terms with), he’s not going to seriously critique them or their work. This would be impolite, for one thing. For another, it might be grounds for a lawsuit, if he wasn’t careful.

So instead of referring to a real Heavy Metal artist, he makes one up. Because he has some highly critical things to say about this style of artistic expression. Fair or not. He’s got a bone to pick. And this is most definitely his opinion, conveyed through Tom. Because, you see, the illustration that Dewey intends to put in place of The Adoration of the Magi, a Dürer woodcut that Mr. Dürer will not be demanding payment for, is a sort of acid trip comic strip version of The Night Before Christmas, with a freaked out Santa, a low-rider sleigh, and a libidinous half-naked Afro’d Nun. And that’s perfectly fine in its place (namely Heavy Metal), but its place is not Tom’s book. And he wants us to know why that is.

What’s wrong with Korban’s work–apart from the thuggish crudity of the mind behind it–is what tends to be wrong with a lot of things directed at young people; it’s nihilistic for fun. In a nervous effort to be knowing before they know anything, not to be taken in, a lot of kids throw out the sentiment with the sentimentality and are left with nothing but surface. Then they try to replace what they’ve lost by being sentimental about themselves. (None of this is new, of course; remember “Teen Angel?”)

But the caustic harshness still such a strong element in this tripe is a leftover from the anti-war, pro-drug sixties, and is nastily inappropriate in the me-first eighties. It is true that some of the contributors to The Christmas Book are cynical about Christmas, but it’s an earned cynicism. Korban may have earned his fifteen hundred dollars, but he hasn’t earned his attitudes, and I won’t have his work in the book.

So at first Dewey is in trouble, but once it becomes clear that Korban is going to have his money or else, and payment is made, and Tom absolutely refuses to allow the purchased material to be used in his book, they start looking at him as if this is all his fault. And all of this fol de rol has delayed sending the book off to the printer, but some preliminary copies are made up, and Tom is happy–it’s what he wanted. It’s the book he meant to create. He’s finally done something he can be proud of. And because of all the famous names attached to it, people will see it. Or will they?

Tom is served with a summons. He’s being sued. The publisher is being sued as well. Because it turns out a woman out in the midwest somewhere (I know I could look it up, but I don’t want to) had an idea for a book about Christmas (her favorite holiday) that was going to feature many of the same famous writers as Tom’s book, not that any of them ever wrote anything for her, because she didn’t have a publisher to back her up. She sent a letter detailing her idea to Craig, Harry & Burke, before Tom approached them with his idea, not that Tom ever heard of it. And did I mention she’s in an iron lung? It’s her dying wish to see this book of hers in print.

So Tom’s original vision was not so original after all, and so what? You can’t copyright Christmas. You can’t copyright the idea of an anthology of famous writer and artists giving their personal impressions of a holiday. And you can’t persuade a bunch of hick lawyers who don’t know anything about this area of law that they don’t have a goldmine here with all these famous names involved; at least not without spending years in court first. So Tom is forced to compromise and let this woman’s name be on the book. Okay, fine, whatever, done. Can he have his book in stores now?

Nope. The workers at the printer chosen for his book choose this precise moment in time (for sound strategic reasons) to go on strike. It’s too late to change printers. It’s too late to get the book in stores for Christmas. The whole point of the book was to have it in stores for Christmas. That’s what a Christmas Book is. And by next Christmas, the rights to all the material that isn’t in the public domain will have reverted to its various creators, who would need to be paid all over again in order to use it. It’s in the contract Tom’s agent drew up and if she hadn’t drawn it up that way, they’d never have resolved the lawsuit, and they’d be screwed anyhow. There is no Christmas Book. C’est fini.

So Tom suffers a major professional defeat–having already suffered a personal one. His long war with Mary is over–he moves back in with her. She changed her strategy–stopped coming up with excuses for him to come over to do something for the children, stopped telling him about all the passes she had to deflect from horny guys, and she just listened.

Once she had him at the apartment working on his book all the time, those ruses were no longer needed–she knew all along all she needed was to get him back home, and the pull of home itself–of the family he’d half-abandoned–would seduce him more effectively than anything else possibly could. She finally lets go–at which point he realizes he doesn’t want her to let go. So he tells Mary he’s moving back in, and at the very same time tells Ginger he’s moving out.

(And the infuriated and incredulous Ginger, who we know will be perfectly fine once she gets over the indignity of having been dumped, never tells Tom she had sex with her ex at least once while he was living there in Tom’s office, even though it’s made really obvious in that chapter, and Tom can be incredibly dense for such a smart guy, and I have no trouble at all buying that–the smarter the guy, the denser he is about such matters, I’ve always found, and I would know. What I don’t know is if that’s a self-deprecating comment or an egotistical one.)

So the Holy Family is reunited, Tom and Ginger’s two sports-obsessed sons remain chums, Lance continues his search for an apartment and a woman (in no particular order of importance), Ginger will get over it someday, Vickie somehow finds a husband before she gives birth (two weeks early–hmm), Dewey Heffernan is royally chewed out by his overbearing father for being such a gawdawful pest (minor subplot, no time), the printers strike labors on, and that lady in the iron lung is still suing Tom over a book that will never exist, except in the form of a few advance copies. Everybody needs a hobby.

Tom puts his advance copy away–proof that he’s more than just a cheap hack–he’s a damned expensive one, seeing how the publisher made out on this deal. He got to keep his advance, and he did convince some people he’s good for more than how-to books, and he and Mary are averaging three times a day until they catch up, so all things considered, he came out ahead of the game.

He’s got other projects going (he’s even going to work with Dewey again, on a book about video games–told you Dewey was a voice of his generation) but he can’t help but believe that somewhere out there in this alternate reality his creator has made for him, there has to be “an ally who won’t quit, get pregnant, or enter second childhood before leaving the first.”

And in the equally befuddling reality Donald Westlake’s creator made for him, such an ally had in fact materialized, in the form of Otto Penzler, and Westlake did in fact write a novel for him that falls within the extremely broad parameters of the mystery genre (if you don’t want to nitpick), and that’s our next book.

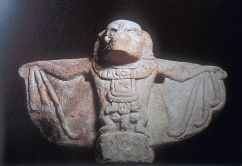

And it is somewhat prefigured in an offhanded comment the now somewhat more harmoniously composed Mr. Diskant makes, while contemplating the fruits of civilization–“I wonder what the Mayans did when things got too confusing.”

You could always ask them.