NUSSBAUM: Now that you have seen several of your creations transferred to film, do you subscribe to the auteur theory, or are you one of those wise-ass scribblers who refuse to acknowledge the artistic superiority and creative transcendence of the director? (Answer by mentioning two American and two foreign directors, one of whom must be French; and relate their work to the young Orson Welles and the imitative product of Peter Bogdanovich: Use more than one sentence if necessary.)

WESTLAKE: I love your question. Remember the scene in The Third Man where Joseph Cotten, the writer of westerns, is posing as a literary-type lecturer? He’s asked a question about James Joyce. If you can find a still of Cotten’s face when he’s reacting to the question, you’ll have my answer to you, sir. But I might have some additional things to say, so why not start a new paragraph and see?

I subscribe basically to the theory that a movie is not the book it came from, and in almost every case it shouldn’t be the book it came from. I have never adapted one of my own novels to the screen. Movies are a different form, they require different solutions.

Al Nussbaum interviewing Donald E. Westlake by mail (the entire piece can be found in The Getaway Car).

By the end of 1967, ten Parker novels had been published under the name Richard Stark. None of them had been best-sellers, but sales had been strong. The reviews had been glowing, the audience had been growing, and Hollywood was starting to take notice. But Hollywood has never been the be-all and end-all of film making, much as it might like to think otherwise, and Richard Stark had many ardent fans who could not read English. Parker translated very well into other languages, it seems. Translating him into other mediums was going to prove a much more challenging prospect.

One place where the Stark books were developing a following was France, where they were published by Gallimard under the Série Noire imprint, which specialized in French translations of American crime and detective fiction of the hardboiled variety, though it also published some very impressive homegrown literature in the same genres. Please note–the French Wikipedia article on Serie Noire has a photograph of Westlake–and mentions Killy, under its French title of Un Loup Chasse L’Autre–(‘A wolf hunting another’).

These books generally had plain black covers with the title in yellow print, and often no cover art–very stark indeed. Parenthetically, a Jose Giovanni Serie Noire entitled Classe Tous Risques (later made into a superb film, like so many of Giovanni’s novels), features a character named Eric Stark (played by Jean-Paul Belmondo in the film). That book came out in 1958–the first short story Westlake sold under the name Richard Stark was published in a science fiction magazine the following year. Coincidence? Yeah, probably. Lot of that going around in this genre.

Depending on which source you’re reading, Gallimard’s Serie Noire books may have inspired the coining of the phrase Film Noir by the French critic Nino Frank–he was originally referring to American films like Double Indemnity and D.O.A (okay the directors of those two were European, what’s your point?), which had been hugely influential in Europe–but French readers of policiers and roman noirs were no strangers to ruthless anti-heroes who came back in book after book–they were way ahead of us there. Back in 1911, the first in a long series of novels about a deadly master criminal named Fantomas appeared–a shadowy figure who evaded definition as easily as he evaded the police–a supervillain you’d probably call him today, but one the reader is invited to admire if not quite identify with.

A later and far less diabolical example would be Géo Paquet, aka The Gorilla, who appeared in a long series of books in the 1950’s–in the first film adaptation in 1958, starring the great Lino Ventura, he breaks out of jail by bending the bars of his cell (he possesses amazing strength, hence the name), and ends up embroiled in a plot involving stolen nuclear secrets. And I wish I knew more, but all the sources are in French. I’d watch any Lino Ventura movie, so hopefully it’ll pop up on DVD here in the states.

I wish I could begin to express my stunned admiration for French noir at its best–master film makers like Jacques Becker, Jean Pierre Melville, Henri-Georges Clouzot. Actors like Gabin, Ventura, Delon, Belmondo, who combined acting ability, star charisma, and often the kind of physical prowess you’d expect from trained stuntmen. What Warner Brothers started in the 30’s and 40’s, these idiosyncratic artisans took up with a vengeance, focusing and perfecting it to a degree that has never been surpassed. When it comes to films about ice cold yet oddly vulnerable gangsters, outlaws, and heisters, with a sang froid you could crack nuts on, there’s the French and then there’s everybody else.

And tragically, none of these masters ever adapted a Stark novel–no, the first Parker adaptation ever was lensed by the one French director who could be guaranteed to have no respect for the form he was dabbling in. Or any other form. Or form, period. Love him, hate him, don’t give a damn about him, you must acknowledge that Jean Luc Godard respected nothing but his own oddball muse, and his main reaction to a well-crafted story with great characters was to turn it upside down and inside out, and unravel every last plot thread onto the cutting room floor. Character? Qu’est-ce que c’est?

I’ve already told the story of how Made in USA came to be in my review of The Jugger. I’ve got nothing to add to that. And zero interest in ever seeing that film again. Once was plenty. When I look at film stills online, I can appreciate the imagery, the sense of composition, and of course Anna Karina–her I could look at all day long. And I can appreciate the weird irony that Parker was first portrayed as a woman–not like it would matter to him either way.

There are maybe one or two scenes in the film that seem to bear any relation to the story Westlake told; even there you have to squint hard to see it. The only actor who is remotely well-cast is the one playing Tiftus (Typhus in the film, ha-ha, très très drôle, maestro). I personally don’t think the film even works on its own incoherent terms–it’s a collage of shout-outs to various American writers, directors, and actors Godard seems to have liked, combined with an affectation at contemporary political commentary that I don’t think anybody really understands (though many pretend to).

The haphazard quality of the piece is not wholly by design: the film’s screenplay, such as it is, was cobbled together at the last possible moment, so Godard could use the same equipment he was renting to make Two or Three Things I Know About Her to simultaneously shoot this film, which he finished in less than two weeks. And let me say, it looks it. To paraphrase Moliere’s misanthrope, “I might, by chance, make something just as shoddy–but then I wouldn’t show it to everybody.”

Godard never gave a damn about the downtrodden of the earth, as I see it–he had a vision, and he wanted to express it, and I can respect that, wish him well of it, and mainly avoid his films, because I don’t like them. This is not aimed at the Nouvelle Vague in general–Truffaut I like, Malle I like, Agnes Varda I adore (and her late husband Jacques Demy); Melville is probably my favorite French filmmaker. We all have our tastes. There are many ways to tell a story, but my impression of Godard is that he never cared about stories at all.

But for all of that, Made in USA set the pattern for very nearly all the Parker adaptations that followed–the people who wrote and filmed them were not interested in doing a faithful adaptation, even if they said they were (Godard, at least, is guilty of no such double-dealing). Something about the character of Parker interested them, or the general heisting milieu, or they just wanted to do a crime picture and they could get the rights to a Parker novel cheap enough (always with the proviso that they couldn’t call him Parker), but they were out to tell their own stories, usually very different from the ones Stark had told.

They had their own vision and worldview to get across, which Stark (and Westlake) would generally feel little affinity towards (Westlake had nothing to say about Made In USA, other than it was ‘a rotten movie’, and I think that’s the film buff in him talking, not the writer who got cheated out of his pay). Also, not surprisingly, none of them had the nerve to show Parker the way he is in the books, because he does horrible things to people, with not so much as the slightest pang of guilt, and gets away clean in the end, usually with a lot of money. Screen versions of Parker can get away with robbing other crooks–sometimes–somehow, second-hand theft is okay. Whatever.

Donald Westlake was well aware of the fact that the main point of any film based on a book is not to literally transcribe the printed page into imagery and dialogue. An excessive concern with fidelity to the source can do more harm than good. The point is to make a good film–but he also felt strongly that the script should at least attempt to convey some essence of what the original writer had been trying to say. Godard’s film would have to be considered the worst in this regard–but the other French adaptation of a Parker novel was, by this standard, far and away the best.

And far and away the hardest to see, but I got lucky. Almost exactly a year ago, I was able to see a pristine print from La Cinémathèque Française unreeled at the Museum of Modern Art–no subtitles, but they had a screen under the screen where titles could be shown. Packed house that night. It is apparently possible to download a version screened for television years ago (pan&scan, I assume), but I’ve never done this. So I’ll be going by memory, and notes I made at the time.

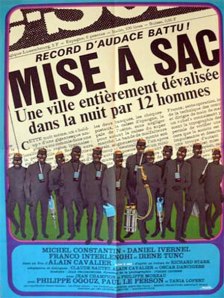

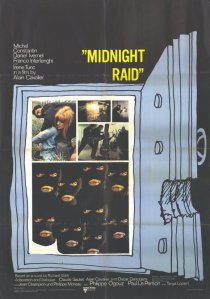

Information about Mise à sac (often translated as Pillaged) is hard to come by–particularly in English. It’s a little-known film outside of France, though it seems to have had some kind of release somewhere in the English-speaking world under the title Midnight Raid. Its director, Alain Cavalier, a protege of Louis Malle, would not generally be considered to occupy the first rank of auteurs, but as one of the few surviving names from an exciting era of filmmaking (he’s eighty-three, and still working), who worked with talents like Catherine Deneuve, Romy Schneider, and Jean-Louis Trintigant at their peak, he’s somebody any serious fan of classic French cinema should be familiar with.

As they should be aware of Claude Sautet, who shared a screenwriting credit with Cavalier on this film–he’s better known for writing and directing that very film adaptation of Classe Tous Risques I mentioned above, where Jean-Paul Belmondo played Eric Stark. And again, I’m almost sure that’s a coincidence, but they do start to mount up after a while, don’t they?

The way Cavalier and Sautet went about adapting a Stark novel was in total contrast to Godard–first of all, in that there was no legal confusion over the film rights, leading to a lawsuit. Westlake was properly paid for The Score, and there can be no question at all that the screenwriters studied the book closely–whether it was Cavalier’s idea to make a film of it, I don’t know, but once he was actually doing so, it seems to have been his intention to get as close to the spirit and letter of the novel as possible–within reason, of course.

You can’t very well do a perfectly faithful adaptation of a book that opens in Newark New Jersey, and whose principal action is in a western mining town, if it’s set in France. Some translation of setting and motivation and general cultural milieu shall be required. And while French noir tends to be much less inclined to moralize than its Hollywood equivalent, you rarely ever see criminals profit from being criminals in it–usually crooks die or get caught in the end, and when they don’t it’s usually because they didn’t actually commit the crime they intended to commit. Law & order must prevail in the end–the question is how and to what extent.

And also, I would say, the influence of existentialism, and a general attitude of fatalism that permeated French filmmaking at this time, led to a sense that these individualists, however admirable on some level, will have to pay the price for being individualists–life will always find a way to bring down those who rebel (which does not necessarily make their rebellion less admirable). The best French noirs tend to be tragic stories–of powerful uncontrollable personalities on collision courses, with each other and with destiny, and the most they can generally hope for is to remain themselves to the (very) bitter end.

But I must say, I don’t quite see that in this film. I see the general style and mindset of French noir in Mise à sac, but I also see much of the Starkian ethos in it–you will be rewarded or punished not in accordance with whether you toe the line, but rather with how well you know yourself and your profession. I get the sense that Cavalier left himself open to the material he was adapting more than any other filmmaker, before or since. He got infected by it, discovered an affinity with it. And for this we can only commend him, while recognizing that it’s still his vision on the screen, and that he, like everyone else to date, has not given us a true cinematic incarnation of Parker. Parker remains untranslatable.

What did Westlake think of Mise à sac? He told Patrick McGilligan that he’d sold the rights via the usual channels, and had never once spoken to anyone who worked on the film. Some time later–presumably in the VCR era–he saw it at a friend’s apartment in Paris–probably taped off the air, and not letterboxed, so hardly as the filmmakers intended it to be seen. He did not know French, and there were no subtitles, but “I figured I knew the story. It looked modest but good.” It looked a whole hell of a lot better than that to me, but modest it is, yes. It just wants to tell you a story. No pretensions of any kind here.

The film opens with the Parker character, called only Georges here (I think that’s a first name), heading to a meeting about a potential job, in the city of Lyons. He realizes a man is following him, and he waylays him–and roughs him up–doesn’t have to kill him, as happens in the book. I guess Cavalier felt like a dead body in Lyons would attract more attention than one in Newark, and he probably had a point.

Georges raises a stink about being tailed when he gets to the meeting, but the mastermind of the heist (with the first name Edgar, instead of the last name Edgars) calms him down and does his presentation–where he proposes to rob an entire factory town in a remote rural area of central France. Everyone is suitably taken aback by the audacity of this plan; Georges has serious reservations, but it all goes much as it does in the book–the money and the challenge are too good to pass up.

Nobody is named Grofield here, but there’s a Paulus, a Wiss, and a Salsa. The Grofield character is named Maurice, and he’s not an actor (and frankly, he’s not that interesting). They’re a merry crew of heisters, joking back and forth, enjoying each other’s company. The personalities are not as well-defined as in the book–it’s hard to convey in a film what Stark does with his thumbnail portraits–but the actors do a great job making us believe in these guys–they look like workmen preparing to do a job, and that’s precisely what they are.

The Edgars-Jean-Parker triangle is dispensed with rather quickly–Edgar has hired a callgirl, and Georges, worried about Edgar’s professionalism–sensing something wrong with him–exchanges a few words with her, to see if he can learn anything. She is not seen again.

The heist begins 25 minutes into the film, and takes up most of it–unusual for a Parker adaptation, and only slightly less so for a Parker novel, but this is an adaptation of The Score, and that one really is all about the heist. Just like Copper Canyon, this town basically sleeps at night, and there’s an eerie quiet on the streets. And then this small caravan of vehicles appears, and the game’s afoot.

And just like Parker, Georges patrols those streets in a commandeered police car, while the police themselves are locked up in their own jail–along with the unfortunate young man who sees a robbery in progress, and tries to call it in–the expression on his face when Georges shows up at the phone booth to ‘arrest’ him is priceless–we get to see him in bed with his very pretty girlfriend shortly before (she’s got lovely breasts–on full display–vive la france!), and we, like he, are wondering why he didn’t just stay in bed.

I actually think this is an improvement on the scene in the novel–the hapless young lover in that one just ends up bound and gagged in an alleyway, catching a bad cold–but that’s because in the novel, the police station is going to get blown up, and Westlake didn’t want to kill the poor kid. Here, Cavalier takes full advantages of the topsy-turvy scenario of the novel–the way the criminals have become the police, and the law-abiding citizens are tossed behind bars simply for getting in the way of a smooth-running operation.

In the meantime, Maurice is watching the telephone exchange, and making time with one of the operators, who is of course a lovely young woman named Marie. She’s attracted to him, but she’s not trying to persuade him to take her along. He’s no Grofield, I think I mentioned.

The middle of the picture, dealing with nothing more than the systematic pillaging of all the major businesses in town, is quite simply a joy to behold. The most perfect translation of a Stark novel you could imagine. You’ve still got to stick the landing, and that’s where things get a bit messy.

Edgar, like Edgars, has a vendetta against the town–only this time it’s much more personal and specific. He’s not a disgraced police chief here–he was fired from his position at the local plant by the owner and manager, and one gets the feeling he originally just thought he’d get his revenge by stealing everything in town, including the factory payroll–but as he looks at the beautiful house this man lives in, he decides it’s not enough. He doesn’t want to burn down the entire town–just the man’s house, with him in it. There’s a woman involved somehow, but I only saw this once, a year ago, so the details are a bit hazy.

Georges realizes something is wrong, and confronts him–and somehow Edgar knocks him down. Which you know was never going to happen to Parker, but this ain’t Parker. Coulda been, shoulda been, woulda been, but no cigar.

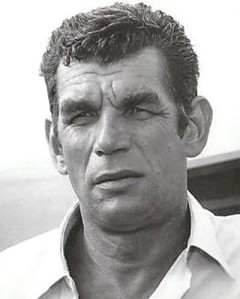

I should talk about Michel Constantin now. He was never a big star, or really a star, period–this is probably the most central role he ever played in a film. He was always the heavy, or the sidekick, though greatly prized in that type of role. He made his debut in the classic Jacques Becker prison escape picture, Le Trou, and let’s just say his acting skills never really got past the basics–but he exuded a certain authenticity.

(That’s not from Mise à sac, but you see what I mean, right?)

He was only 6’1, but seems much taller on film. He tends to loom over the other actors (not a lot of tall people in these movies). He just looks big–and blocky–and shaggy–and ugly, but somehow you know it’s the kind of ugly that gives at least some women vibrations above their nylons. He walks in a certain indefinable way, with his big veiny hands swinging at his sides, and you just go “right”. He’s Parker. Until he opens his mouth.

See, he has to speak the dialogue he’s been given, and he’s got to react the way the director tells him to, and Cavalier isn’t trying to give us the Parker from the books. He either doesn’t want that, or doesn’t know how to convey it. He’s interested in telling a story about a group of thieves pulling a daring robbery–he’s interested in the subversive nature of that robbery, and the interaction of the robbers with the townspeople, and the whole notion of what happens when a little town is asleep.

But he’s not giving us the mythic lethal enforcer, the master planner, the wolf in human form, and certainly not the guy who has no sex drive until after he finishes a job–I’d guess he thought that would detract from the gritty realism he was going for with this scenario–bit late to argue with him now. To see things from his POV–he doesn’t have a star–none of these actors, talented as they are, were big names. It’s an ensemble piece, and that is in fact one of its strengths, but there is still a vacuum at the center, where Parker ought to be. And isn’t.

Georges is a rather polite soft-spoken fellow, who laughs and jokes readily, reacts with horror to Edgar burning down the plant manager’s house, and seems entirely human–nothing terribly enigmatic or unaccountable here. He conveys Parker’s professionalism, his calm, but the only time he shows us the more frightening side of the character is when he comes up behind a guard at the factory in the darkness, looking like something out of a horror movie (the spare and effective background music sounds like a horror score at points), and takes the man out hard–at which point one of his colleagues exclaims angrily “Oh, so we’re killing people now?”

Actually, it’s a good question–why kill a guard when you don’t have to? It’s not clear whether the man is actually dead. But that’s basically the only serious act of violence committed by Georges in the whole movie. Cavalier didn’t really do violent films–it wasn’t his thing–and this is his only real crime film that I know of.

He obviously loves the material, but he’s a bit restrained about it. He’s depicting a small French town being despoiled by brigands–not in the past, but in the time period he’s making it in–and he’s worried people might think he’s saying crime pays. He’s only dabbling in this genre, and the fact is, heist movies in general–regardless of nationality–hardly ever play out the way a Richard Stark novel does.

And it doesn’t–not here. The job is thoroughly spoiled by Edgar’s vendetta–he ends up dead in his own fire, and the rest of the gang flee with the loot, but they aren’t in the American west–they can’t disappear into a vast uninhabited landscape and hide out until the heat dies down, as happens in the book–there’s farms all around the town. There’s a lot of cops. There’s no place they can hide in the country. Their plan was to get out of town before anybody knew what was happening, and get to Lyons or some other big city where they could blend in. The plan in the book wouldn’t work here, and Cavalier doesn’t really want it to work. This money was stolen from honest citizens. Something must go wrong.

The truck with the loot gets stuck in the mud of a small access road they’d hoped to avoid the cops on. Georges and the others make a run for it. Maurice is hung up on Marie, who he’s taken along as a hostage, and can’t accept the money is lost–it slows him down enough to get caught. The police close in with tracking dogs (Parker might actually watch this part of the film with interest), and nab most of the crew. But Georges and one of the other heisters make it to a small village, wait calmly for the bus, and get away clean. Georges didn’t get the money, but he didn’t forget who he was, and what he was there for, so he lives to steal another day–that, at least, is Starkian morality. And it’s the end of the film. Roll credits.

I loved it, but with obvious reservations. Parker isn’t Parker, which is made all the more frustrating by the fact that they had an actor exceptionally well equipped to play Parker. The Grofield/Mary subplot is basically gutted of all the things that make it work, and comes across as a petty distraction. There isn’t really time for the last act, with the heisters hiding out after the job, police helicopters overhead, tensions quietly mounting, Paulus freaking out, and Parker insisting Mary has to die–but it’s sorely missed. And of course Georges doesn’t go back and have sex with Edgar’s girl, who wasn’t really his girl anyway, but it would have been a nice finishing touch (did Constantin ever get the girl, in any film he ever made?)

I agree with what Westlake told Al Nussbaum in that quote I put up top, but when you start throwing out whole chunks of story in a book this tightly plotted, it’s bound to create problems. It’s like you’re in a plane, and you’re in a hurry to reach your destination, so you start tossing out bits and pieces of machinery to lighten the load, hoping none of them are essential. Probably not a good idea. But at least Cavalier mainly refrained from adding entirely new storylines and characters of his own devising, in place of the jettisoned material–which would be a problem with most of the later adaptations.

It’s a terrific little film, but it’s not The Score–and that’s going to be a recurring theme with all these pictures, good and bad. Most of them have great moments. None of them come close to the books they’re adapting–but overall, I’d have to say this one came the closest. And naturally, in the perverse universe we live in, this means that it’s the most impossible one to see, and may never get a DVD release, because the rights are reportedly all tangled up, and with no stars in the cast, there might not be enough potential profit involved to get them untangled anytime soon. C’est la guerre.

But for a good 30-40 minutes, watching this film, I was transfixed–for all that something is lost in the translation, something is gained as well–there are things a novel can do that a film can’t, but the opposite is also true, as Westlake acknowledged. In terms of story and character, Mise à sac falls quite a bit short of its model, but visually, it has distinct pleasures of its own–what Westlake has to describe, it can simply show us, and it does so with a quiet efficiency, and just a touch of grim humor. A great film it’s not, but it doesn’t pretend to be. It just tells us a story, and since the story is by Richard Stark, it’s well worth hearing–and seeing.

Much as I like the title I came up with for this, I don’t in fact know for sure the order in which the first three Parker adaptations were shot. Mise à sac got released in France a few months after our next film was released in America, but release dates and production dates are two entirely different things. Based on what Westlake told Patrick McGilligan, the two films described here were the first to go into production, but if so, the third film was not far behind them.

And the third film, in terms of sheer visual panache, not to mention star power, is far ahead of all of the Parker films. It is, in fact, a great film (whatever the hell that means). But it’s also kind of a shitty adaptation. And that shall be the point I try to convey next time, assuming I don’t draw a blank.

PS: Actually none of these films are the first Westlake adaptation–and neither was The Busy Body with Sid Caesar. The first-ever film adaptation of anything Westlake wrote was Le commissaire mène l’enquête, in 1963. It’s an anthology film, and one of the episodes is based on Westlake’s short story Lock Your Door, which was first published in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine in 1962. So any way you look at it, the French shot first, n’est ce pas?