“The thing is,” Andy explained, “when I feel I need a car, good transportation, something very special, I look for a vehicle with MD plates. This is one place where you can trust doctors. They understand discomfort, and they understand comfort, and they got the money to back up their opinions. Trust me, when I bring you a car, it’ll be just what the doctor ordered, and I mean that exactly the way it sounds.

Looking dazed, Anne Marie said, “You people are going to take a little getting used to.”

“What I do,” May told her, sympathetically, “is pretend I’m on a bus going down a hill and the steering broke. And also the brakes. So there’s nothing to do but just look at the scenery and enjoy the ride.”

Anne Marie considered this. She said, “What happens when you get to the bottom of the hill?”

“I don’t know,” May said. “We didn’t get there yet.”

It wasn’t a car that came for Max forty minutes later, it was a fleet of cars, all of them large, all except his own limo packed with cargos of large men. He couldn’t have had more of a parade if he were the president of the United States, going out to return a library book.

His own limo, when it stopped at the foot of the steps from the TUI plane, held only Earl Radburn and the driver. Earl emerged, to wait at the side of the car, while half a dozen bulky men came up to escort Max down those steps, so that he corrected that image: No, not like a president, more like a serial killer on his way to trial.

The president image had been better.

It came up in the comments section last time, and bears mentioning here–this novel marks the total reversal of the original Dortmunder/Kelp dynamic. In the first three novels, Kelp brought Dortmunder a crazy-sounding job, the job would go sour, and Dortmunder would blame Kelp, call him a jinx. Then work with him again in the next book.

This couldn’t go on indefinitely, so in the next five novels, somebody else brought Dortmunder the job, or, in the case of Why Me?, the job was a simple one-man burglary that suddenly got very complicated. Kelp might be help or hindrance, usually both.

This book starts with somebody bringing Dortmunder a job; a simple two-man burglary, that suddenly gets really complicated. The billionaire Dortmunder is ostensibly robbing robs Dortmunder instead. Takes a supposedly lucky ring May gave him right off his finger. Humiliates him. Dortmunder wants his lucky ring back. He needs help. He has to track down this billionaire and take that ring off his finger personally, to undo the insult. It’s about self-respect, not money.

So he calls Kelp in, and Andy is atypically hesitant–this job sounds crazy! Dortmunder has to sell him, and in the end it’s not loyalty that makes him agree–it’s that Dortmunder, who has been the real jinx all along, is suddenly himself a good luck charm. Now that he doesn’t have the ring. Now that he could care less about money, he’s making money hand over fist. Everybody wants to work with him now. He’s got the Midas Touch.

First he went back to Max Fairbanks’ house in Carrport LI, and pillaged it, all by himself. Then he got together a four man string to hit an apartment in a theater/hotel complex Fairbanks owns. Everybody made out great from that score. But both times he missed Fairbanks, and Fairbanks is wearing the ring, never takes it off, because it bears his corporate symbol, the I-Ching trigam Tui, and he believes it will bring him good luck (which he’s already enjoyed an obscene amount of). Dortmunder has to catch him offguard somewhere. And the guy has to testify before congress, so he’s going to be staying at a little place he’s got in the Watergate. Because where else, right?

Dortmunder and Kelp should be able to handle that gig by themselves, but they don’t know Washington. Affordable GPS devices are not a thing yet, even for Kelp. They need a guide. Fortunately, Kelp just hooked up with the very recently single Anne Marie Carpinaw, daughter of a 14-term Kansas congressman, abandoned by her husband at the Fairbanks hotel in Times Square. She knows our nation’s capital like the back of her lovely hand. And is ambivalent about it, as she seems to be about nearly everything in her life, Kelp included. Well, when you get right down to it, everybody is ambivalent about that town. Though it can seem awfully stuck on itself.

“The George Washington Memorial Parkway? They really lean on it around here, don’t they?”

“After a while, you don’t notice it,” Anne Marie assured him. “But it is a little, I admit, like living on a float in a Fourth of July parade. Here’s our turn.”

There was a lot of traffic; this being Sunday, it was mostly tourist traffic, license plates from all over the United States, attached to cars that didn’t know where the hell they were going. Andy swivel-hipped through it all, startling drivers who were trying to read maps without changing lanes, and Anne Marie said, “Now you want the Francis Scott Key Bridge.”

“You’re putting me on.”

“No, I’m not. There’s the sign, see?”

Andy swung up and over, and there they were crossing the Potomac again, this time northbound, the city of Washington spread out in front of them like an almost life-sized model of itself, as though it were still in the planning stages and they could still decide not to go through with it.

Basically this entire chapter seems to exist for the purposes of telling people who want to visit our nation’s capital that they really do not want to drive there, but Anne Marie gets them through the urban maze unscathed. The stolen car with MD plates having been abandoned, John and Andy still have to scope out the Watergate complex, while May and Anne Marie (who get along great from the start) go shopping and sight-seeing, but in fact they do a better job casing the joint as well–join a group of prospective renters touring the apartment complex, find out everything the guys needed to know.

And turns out the joint is empty when they break in (this isn’t a residence, just a place to crash when Max is in lobbyist mode, so no valuable art to steal). They set up camp there and wait. Dortmunder is disgusted. Andy is somewhat more enthused, because there’s fifty thousand dollars in bribes, I mean PAC money, waiting there for a Fairbanks aide to take it to various recipients, as they learn from the answering machine message the underling left, referring to the ‘PAC Packs.” Possibly to be put in a Fed-Ex PAK. Dortmunder is irritated by all the variant spellings of ‘pack’ (as his creator would have been). Andy is just delighted to see this unexpected dividend. And horrified when John doesn’t want to take it.

See, Dortmunder figures Fairbanks has to show up at some point, but this employee is going to show up for the cash, and if he doesn’t find it, he might call the cops, and he’ll certainly call Fairbanks. John is adamant–if it screws up his getting the ring back, they can forget about the Fifty G’s.

Kelp’s agile mind searches feverishly for a work-around, and he says they’ll leave a note saying Fairbanks’ secretary took it for distribution. Dortmunder grudgingly agrees, and they leave with the money, figuring they’ll come back later for Fairbanks and the ring.

(Anne Marie is doubled over with laughter when she hears about this–“At last,” she said, when she could say anything again, “the trickle-down theory begins to work.” )

But before they can go back to the apartment to try again for the ring, Wally Knurr calls, saying that Fairbanks won’t be staying at the Watergate apartment after all, and that his location will no longer be made known to his corporate empire at large–so Wally won’t be able to track him via the internet anymore. What gives here? Well, Mr. Fairbanks, staying at his beachfront condo in Hilton Head, has been consulting The Book, as he calls it. And the ancient wisdom of the Orient is urging caution.

Thunder in the middle of the lake:

The image of FOLLOWING.

Thus the superior man at nightfall

Goes indoors for rest and recreationHmmm. The Book often spoke of the superior man, and Max naturally assumed it was always referring to himself. When it said the superior man takes heed, Max would take heed. When it said the superior man moves forward boldly, Max would move forward boldly. But now the superior man goes indoors? At nightfall? It was nightfall, and he was indoors.

(At this moment in time, unbeknownst to Max, Dortmunder was breaking into his apartment at the Watergate for rest and remuneration, which for him amounts to the same thing.)

He probes further into the text, which is suggesting that someone is following him. Could it be the annoying Detective Klematsky, who suspects him of burgling his own residences for the insurance? He needs more information, so he does another coin toss, this one leading to a hexagram–The Marrying Maiden. Max doesn’t like that one. He strives for the proper interpretation, and suddenly it comes to him–the ring! That burglar is coming for his ring!

And Max is as perversely determined to keep the ring as Dortmunder is to regain it. So this is why he never came to the Watergate apartment as planned, and this is why he’s made his movements a secret, even to most of his employees. But there’s one trip he can’t conceal–he needs to go to his casino in Las Vegas. And it occurs to him that this thief will make a try for the ring there–so he can set a trap. He shall yet prove he, Max Fairbanks, is the superior man, not this bilious brigand!

So Max heads for Vegas, making the needed arrangements with his security staff to nab Dortmunder in the act of lèse-majesté. While Dortmunder begins to put together a string for what will prove to be his biggest and best heist ever.

In the meantime, Andy Kelp has one of his little tete-a-tetes with his friend Detective Klematsky at a New York restaurant, a New Orleans themed eatery this time. And weirdly, this time Klematsky is buying. Because he’s the one that needs information. He wants to know if his old friend Kelp has heard about any people in his profession doing fake burglaries as part of an insurance fraud scam.

He knows that Andy’s eyes blink rapidly when he tells a lie. What he doesn’t know is that Andy can do that on purpose too. So Andy tells him he never heard about anything like that, his eyes blinking furiously all the while. Telling Klematsky exactly what he wants to hear, while pretending to do nothing of the sort. Like Alan Grofield (the Stark version of that character), Andy Kelp can even lie with the truth. And confirmed in his suspicions, Bernard Klematsky, who finds insurance fraud particularly offensive, is now determined to arrest Max Fairbanks for one of the very few white collar crimes Max Fairbanks is not guilty of.

And as Dortmunder enters the O.J. Bar and Grill, we get another scintillating discussion relating to issues of the day, while Rollo the bartender attempts to put up a new neon beer sign.

“It’s a code,” the first regular was saying. “It’s a code and only the cash registers can read it.”

“Why is it in code?” the second regular asked him. “The Code War’s over.”

A third regular now hove about and steamed into the conversation, saying “What? The Code War? It’s not the Code War, where ya been? It’s the Cold War.”

The second regular was serene with certainty. “Code,” he said, “It was the Code War because they used all those codes to keep the secrets from each other.” With a little pitying chuckle, he said “Cold War. Why would anybody call a war cold?”

The third regular, just as certain but less serene, said, “Anybody’s been awake the last hundred years knows, it was the Cold War because it’s always winter in Russia.”

The second regular chuckled again, an irritating sound. “Then how come,” he said, “they eat salad?”

The third regular, derailed, frowned at the second regular and said, “Salad?”

“With Russian dressing.”

After a while, they start arguing about what the code is called–zip?–civic?–Morse? Rollo the bartender tries telling them it’s called a bar code, and is accused of having a one-track mind. And you have seen far weirder and more uninformed conversations than this happening online, probably participated in a few, and there wasn’t any beer being served during them. Think you’re so smart. Hmph.

Dortmunder is not kidding around with this job. He’s calling in the heavy artillery. If you know of anything heavier, all I can say is, I surrender. This cannon already settled the argument up front by demonstrating a cold cure that involves squeezing all the bad air out of a person.

Kelp continued to hold the door open, and in came a medium range intercontinental ballistic missile with legs. Also arms, about the shape of fire hydrants, but longer, and a head, about the shape of a fire hydrant. This creature, in a voice that sounded as thought it had started from the center of the earth several centuries ago and just now got here, said, “Hello, Dortmunder.”

“Hello, Tiny,” Dortmunder said. “What did you do to Rollo’s customers?”

“They’ll be all right,” Tiny said, coming around the table to take Kelp’s place. “Soon as they catch their breath.”

“Where did you toss it?” Dortmunder asked.

Tiny, whose full name was Tiny Bulcher and whose strength was as the strength of ten even though his heart in fact was anything but pure, settled himself in Kelp’s former chair and laughed and whomped Dortmunder on the shoulder. Having expected it, Dortmunder had already braced himself against the table, so it wasn’t too bad.” “Dortmunder,” Tiny said, “you make me laugh.”

“I’m glad,” Dortmunder said.

Tiny is even more amused to hear Dortmunder’s plan–to rob an entire casino. Knowing in advance that Fairbanks will be setting a trap for all of them. Vegas is a hard target at the best of times. But casinos are one of the few places left in this modern electronic world that have a whole lot of untraceable cash on hand. And in the midst of yukking it up over Dortmunder’s recent professional embarrassment, he’s been hearing about all these amazing scores that follows it. He’s listening.

So are Stan Murch and Ralph Winslow–the latter a lockman who is known for always having a glass full of liquor and ice cubes in one hand. A string of five is usually as big as Dortmunder wants to get–he likes to say that if a job can’t be pulled with five guys, it’s not worth pulling. But this is no ordinary job, and will require no ordinary string. And it will require a plan. Which falls on him.

“You must have an idea,” Andy Kelp had said at one point, for instance, but that was the whole problem. Of course he had an idea. He had a whole lot of ideas, but a whole lot of ideas isn’t a plan. A plan is a bunch of details that mesh with one another, so you go from this step to this step like crossing a stream on a lot of little boulders sticking out and never fall in. Ideas without a plan is usually just enough boulders to get you into the deep part of the stream, and no way to get back.

Westlake had Kelp say something like this in Drowned Hopes, and clearly he’s talking about more than heists here. A novel, you might say, is a bunch of details that mesh with one another, right? Westlake liked to write from what he called the ‘push’ method of narrative storytelling, where he would start with some basic ideas, and then push forward into the story, working things out as he went, listening to the characters, minding the terrain. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t. Fact is, a plan worked out perfectly in advance of a job is one of those things God loves to laugh at (along with Dortmunder).

He can’t work it all out without going there and seeing the lay of the land. Knowing who he’s working with, what tools he has in the kit. And the string keeps growing by leaps and bounds, as more and more old associates, many of whom have not been seen in some time, volunteer for this Vegas casino heist. You might say they’re an all-star cast. Or you could come up with some ruder term. Something rodentine, perhaps?

Let’s lay it out. Planner: John Dortmunder. Drivers: Stan Murch and Fred Lartz (and his wife Thelma, who does all the actual driving in the Lartz family these days). Lockmen: Ralph Winslow, Wally Whistler, and Herman X (who is now just Herman Jones, after doing a stint as Herman Makanene Stulu’mbnick in Africa, and being a Jones must make life much simpler for a thief, all things considered). Utility infielders: Andy Kelp, Tiny Bulcher, Gus Brock, Ralph Demrovsky, and the frequently unfortunate Jim O’Hara (but not this time, baby).

That’s either twelve or thirteen (depending on whether you count Anne Marie, along for the ride, much to Andy’s consternation), and we’ve seen Westlake put on this kind of passion play before, in The Score, and Butcher’s Moon–one more indication that a long-buried alter-ego is stirring within him–but there’s also seven unnamed associates in the string, for a grand total of twenty. Even Parker never had a string that big. Or a target this well-guarded.

Most of them come down from New York with Andy and Tiny, in a purloined mobile home, an Invidia, and of course Westlake made that name up, along with a bunch of other fictional mobile homes they considered at a dealership in New Jersey, before deciding this was the one they wanted to steal. There were Dobermans guarding the dealership, but they got some nice raw hamburger with happy pills inside, and went happily to sleep, dreaming of rabbits. Cute.

But all this time, Dortmunder has been checking out the scene in Vegas (with Kelp, who then heads back to New York to round up some needed items, as mentioned). And everybody who sees Dortmunder figures he’s up to something, which of course he is, and they’re all telling him forget about it. Vegas is a burial ground for guys with big plans. He keeps insisting he’s just a tourist, here to see the sights, try his luck. “Uh-huh” they keep saying–the waitresses, the motel clerk, everybody. He just does not look like the sight-seeing type, and the only gambling establishment he’d fit in at would be a racetrack.

The security men spotted him as a ringer almost immediately when he showed up at the casino, but Kelp got him some new clothes. Which are very definitely going to stay in Vegas when he goes.

The pants, to begin with, weren’t pants, they were shorts. Shorts. Who over the age of six wears shorts? What person, that is, of Dortmunder’s dignity, over the age of six wears shorts? Big baggy tan shorts with pleats. Shorts with pleats so that he looked like he was wearing brown paper bags from the supermarket above his knees, with his own sensible black socks below the knees, but the socks and their accompanying feet were then stuck into sandals. Sandals? Dark brown sandals? Big clumpy sandals with his own black socks, plus those knees, plus those shorts? Is this a way to dress?

And let’s not forget the shirt. Not that it was likely anybody could ever forget this shirt, which looked as thought it had been manufactured at midnight during a power outage. No two pieces of the shirt were the same color. The left short sleeve was plum, the right was lime. The back was dark blue. The left front panel was chartreuse, the right was cerise, and the pocket directly over his heart was white. And the whole shirt was huge, baggy and draping and falling around his body, and worn outside the despicable shorts.

Dortmunder lifted his gaze from his reproachful knees, and contemplated, without love, the clothing Andy Kelp had forced him into. He said “Who wears this stuff?”

“Americans,” Kelp told him.

“Don’t they have mirrors in America?”

And it works. The same security guys who started tailing him the moment he showed his face don’t give him a second look in this get-up. Just another rube contributing to their payroll (as opposed to stealing it). The motel clerk, who has seen them all come and go, just says “Uh-huh.” She may be impressed, but she’d never admit it.

Dortmunder’s plan is starting to come together in his head now. He’s made contact with a former New Yorker, a former heist-man running a perfectly legitimate shady business operation manufacturing cheap knock-offs of famous brands of this or that, fellow named Lester Vogel. He’s quite happy to provide needed materials for the job. Just delighted to hear a New York accent again, accompanied by New York rudeness. A bit confused as to why Dortmunder is expressing interest in tanks of various gases he has on the premises.

And staying at the hotel that goes with the casino, Anne Marie Carpinaw is wondering what the hell she’s doing here, and so is Andy, and yet they do seem to enjoy each other’s company, and quite a lot of sex seems to be going on, though this being a Dortmunder novel, it is only vaguely alluded to in passing. At one point, in her room, she says she’s not sure they belong together, but then he asks her if this is a good time to bring that up, and she says “Well, maybe not.” Not such an unusual conversation for a new couple to have.

She is, however, going to some pains to make sure she doesn’t get rounded up with the rest of the gang if the heist goes sour. She watches a lot of Court TV. Actually appearing on it doesn’t appeal to her.

So all the players have been assembled in one place–even Detective Bernard Klematsky is on his way to Vegas. And little hearkening to any of these impending events, other than his imminent capture and final defeat of that pilfering plebe who should learn to know his place, Max Fairbanks waits at a guest cottage on the casino grounds, his security men instructed to not stay too close to him, so as not to scare Dortmunder away. They are not happy about this, but he’s the boss.

He’s also got to deal with the manager of the Gaiety Hotel, Battle Lake, and Casino, Brandon Camberbridge, a happily closeted gay man, with a wife who happily cheats on him with various non-gay men, a dowdy older secretary who happily serves as a surrogate mother, and he loves his job as much as anyone has ever loved any job in the history of work. And in the course of his conversations with Brandon, Max realizes that this guy actually thinks of Max’s casino as being his casino, and makes a mental note to transfer him elsewhere. Doesn’t pay to let his employees ever forget they are just employees. Only one person actually matters, and that is Max Fairbanks.

Um, yes–the Battle Lake. Las Vegas was, by this time, getting to be more and more about putting on a show for the tourists, and less and less about honest gambling. A theme park with slot machines. The Battle Lake is an artificially created body of water upon which remote controlled full-sized replicas of various warships do ersatz battle with each other, for the edification of the masses. It sounds a bit more Disney than Vegas, but I guess that’s the point–that and the fact that the Tui symbol on that ring Max is defending, and Dortmunder is seeking, means Joyous Lake, and Max’s recent I-Ching readings have been referring obliquely to a lake, and intimating that less than joyous developments are in the offing.

He tries once more to divine his future through the coin toss, and the passages they lead him to, and here’s the thing–it’s pretty clear that in this story, the I-Ching really does work. But convinced as he is that he is a Man of Destiny, Max is doomed to keep projecting what he wants to see onto the auguries of The Book. “When one has something to say, it is not believed.” (And would you believe that every single I-Ching quote in this novel is 100% real?)

He comes very quietly, oppressed, in a golden carriage.

Humiliation, but the end is reached.Well, wait now. Who comes very quietly in a golden carriage? The plane that had brought Max here, he supposed that could possibly be thought of as a golden carriage. But had he been oppressed?

Well, yes, actually he had been, in that he was still oppressed by the thought of the burglar out there, prowling after him. So that’s what it must mean.

It couldn’t very well be the burglar in a golden carriage, could it? What would a burglar be doing in a golden carriage?

Again, Max went to the further commentaries in the back part of The Book, where he read,

“He comes very quietly,”: his will is directed downward. Though the place is not appropriate, he nevertheless has companions.

I have companions. I have Earl Rayburn, and Wylie Branch and all those bulky security men. I have the hotel staff. I have thousands and thousands of employees at my beck and call. The place is not appropriate because a person in my position shouldn’t have to stoop to deal personally with such a gnat as this, that’s all it means.

And that’s why there’s humiliation in it, the humiliation of having to deal with this gnat myself. But the end is reached. That’s the point.

Come on, Mr. Burglar. My companions and I are waiting for you, in our golden carriage. The end is about to be reached. And who do you have, to accompany you?

Oh, he really should not have asked that question. And the Invidia has actually been painted silver, but that’s such a niggling little detail.

Stan Murch, Jim O’Hara, Gus Brock, and the one and only Tiny Bulcher start off the caper. Stan and Jim pose as deliverymen bringing more oxygen tanks for the casino to ‘enrich’ the air inside the casino, encouraging people to stay up later,and lose more money. The tanks are green, from Lester Vogel’s establishment, but what’s inside them is nitrous oxide–laughing gas.

And with a bit of not-too-gentle prodding from Stan, Jim, Gus, and most of all Tiny, the guards prove quite willing to show them just where those tanks need to go. This is an upsetting and painful experience for the guards, as it would be for anyone, but they start to relax shortly afterwards. These are considerate robbers, who bring their own anesthetic.

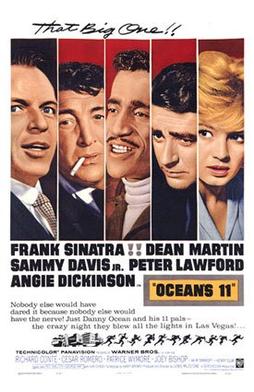

There’s some nice scenes with Herman, posing as one of Max’s employees from Housekeeping, marching right into Max’s guest cottage on the pretense of needing to clean up, Uncle-Tomming his way around Max and the guards–unable to grasp that Dortmunder might have a black associate, or any associate–laughing at them on the inside. (And wouldn’t Sammy have been just perfect to play Herman, back in the day? This is Vegas, I hardly need say which Sammy I mean.)

Herman is done playing around with politics, foreign or domestic. He’s just a straight heister now (well, presumably still bisexual, you know what I meant). He’s going to let his profession know he’s back, black, and better than ever. And I still think Westlake should have given him his own novel, but a bit late now.

So they do the heist. That’s not really important to Dortmunder. Much as these guys may be his friends, they’re still professionals, independents. Nobody’s errand boys. He needed to give them a reason to stick their necks out this far, and money usually works. He’s not leading them–he gave them a plan, and they ran with it. And now the rest is up to him. He wants that ring.

He waits until the string is ready to leave with the loot (two million–more than Parker ever got until Nobody Runs Forever), then he calls the cops, and reports a robbery. And all holy hell breaks loose.

Klematsky picks this moment to try and arrest Fairbanks–he assumes this casino heist is just another insurance scam–Max’s local security man is disgustedly assuming the same thing–explains Max’s odd behavior–he was working with the heisters.

Max, unable to process that he, not Dortmunder, is being arrested, lams it out onto the grounds, as the Battle Lake catches fire, and bits of burning artificial shrubbery are flying everywhere. All he can think now is that he needs lawyers, lots and lots of lawyers. But first he needs someone to get him out of this inferno. A helpful fireman in a smoke mask offers his services. Guess who.

“Give me that ring!”

“No!” You’ve ruined everything, you’ve destroyed–”

“Give me the ring!”

“Never!”

Max, inflamed by the injustice of it all, leaped on the false fireman and drove him to the blacktop. They rolled together there, the false fireman trying to get the ring, Max trying to rip that mask off so he could bite the fellow’s face, and Max wound up on top.

Straddling him. Winning, on top, as he always was, as he always would be. Because I am Max Fairbanks, and I will not be beaten, not be beaten.

You didn’t expect this, did you, Mr. Burglar? You didn’t expect me to be on top, did you, holding you down with my knees, ready now to give you what you deserve, kill you with my bare hands, rip this mask–

And at this point, wouldn’t you know, up runs the normally mild-mannered Brandon Camberbridge, in the grip of a berserker rage. He must have heard about how Fairbanks set up the robbery. His beautiful hotel. Ruined. Pillaged. Ravished. He beats the bullshit out of Max, as so many other of his employees must have yearned to do across the years. And as Max lies there, defeated, barely conscious, Dortmunder, back on his feet, calmly reaches down, takes his ring right off Max’s finger. And that’s game.

As the book concludes, we learn that the insurance fraud charges didn’t stick (because they weren’t true), but in the process of being closely investigated, all this other stuff Max had gotten up to started coming to light. His business, like his life, not to mention his character, could not hold up to close scrutiny. Hey, I didn’t say anything, it’s just a fun crime novel.

So what was it all about? How was this about identity? Sure, we got Anne Marie Carpinaw’s crisis, going from unhappy wife to oddly entertained heister’s moll, and she and Andy will, against all odds, somehow stay together the rest of the series, and I don’t really care.

And we got Andy Kelp himself finding a new side to his identity; more stable, effective, reliable, amorous–but still crookeder than Lombard Street in San Francisco. And we got Herman X/Jones, back from Africa, recommitting to life on the bend, having found that thieves are often more trustworthy than politicians in a developing nation (or any nation). And we got the confused identity of Brandon Camberbridge, the lackey who thinks he’s the boss, to amuse us, and serve as a convenient plot device for the climax.

And this is all entertaining enough, adds to the general fabric of the story, but none of it really matters. This was about John Dortmunder vs. Max Fairbanks. Who was the ‘Superior Man’ referred to in the I-Ching? Who is the Superior Being in any clash of personalities? If you’re Donald Westlake, you’d say it’s the one who knows himself. (Or herself.)

Dortmunder could never, ever, if he lived to be a hundred, think of himself as superior to anyone. The word isn’t even in his vocabulary. He’s been a sad sack and a loser all his life, born under an unlucky star, cursed to be Fortune’s Fool, and he doesn’t kid himself about that. But he knows who he is, and he knows what he’s capable of. Never overestimating himself, he can rise to the occasion when destiny calls. However, he doesn’t waste his time trying to know the future. Not his department.

He tells May he’s not superstitious (while she rolls her eyes a little and says nothing), but he thinks now that ring isn’t lucky after all–he’s not going to wear it again. All its luck must have been used up by her uncle, and now it’s a jinx–losing it meant good luck for him, bad for Max Fairbanks. That’s his explanation for what happened, for how one of the unluckiest guys alive turned the tables on Scrooge McDuck crossed with Gladstone Gander (the Beagle Boys always go to jail in the comic books).

But really, it was more about Max. Max may have started out knowing himself, after a fashion–knowing he was a scoundrel and a liar, knowing that nobody mattered to him but him. And that’s fine, I suppose, in its place–as long as you don’t start taking yourself too seriously. If there’s anything more deadly to an honest unflinching sense of self than being filthy goddam rich, it’s delusions of grandeur–and the two so often go together, you ever notice that?

The oppressed of the world (some of us vastly more oppressed than others) can’t afford delusions of grandeur. We’re too busy trying to survive. And now and again we do come across a Max Fairbanks. And now and again, we do manage, against all odds, to give him one in the eye.

But most of us don’t know ourselves as well as John Dortmunder, it must be said. The Max Fairbanks’s of the world and their delusions can be damnably persuasive. They play on our vanities, as we tickle theirs. So sure, why not take a preening narcissist, an ego in search of a human being, a megalomaniac who can never have enough power, a seething mass of resentment, misogyny, racism, petty tyranny, and rage, and make him the most powerful man on earth? With nuclear weapons to boot. What’s the worst that could happen?

The thing about Dortmunder is, he’s not a killer. But the ‘hero’ of our next book learns, to his amazement, horror, and disturbed satisfaction, that he’s a damned efficient killer. And he can’t afford to indulge his newfound gift on personal vendettas. He’s got to use it for job-hunting. And I’ll have to write a little intro to this one, before I get to reviewing it. And I’ll do that. After I bury my father. Not a metaphor.

Hey, the Ax falls on all of us, sooner or later. That is a metaphor. I hope.