The three of us were together now in Q and I knew from old experience that anyone in Q would sell his old mother for a pack of cigarettes. But all the same, I was puzzled and depressed. Puzzled because I couldn’t clarify what I had really meant to say when I got up to speak at the meeting, depressed because if there was no liberty which I could define then equally there was no escape. I remained awake for hours that night thinking of it. Beyond the restless searchlights which stole in through every window and swept the hut till it was bright as day I could feel the wide fields of Ireland around me, but even the wide fields of Ireland were not wide enough. Choice was an illusion. Seeing that a man can never really get out of jail, the great thing is to ensure that he gets into the biggest possible one with the largest possible array of modern amenities.

From the short story Freedom, by Frank O’Connor

“Tile,” Parker said. “It’s a tile wall.”

Mackey reached in to pull a strip of the Sheetrock away. He held it in both hands and they looked at the face of it, which was pale green “It’s waterproofed,” Mackey said. “We found a bathroom.”

Williams said “We won’t know if there’s a mirror on it until we break it.”

“A mirror in a bathroom,” Mackey decided, “this far to the back of the building, isn’t gonna wake anybody up. If it comes down to it, I’ll volunteer for the bad luck.”

“We’ve got all the bad luck already,” Williams told him. “Parker and me, we already broke out once, and here we are again.”

Picking up a hammer and screwdriver, Parker said “We’re running out of time,” and went back to work.

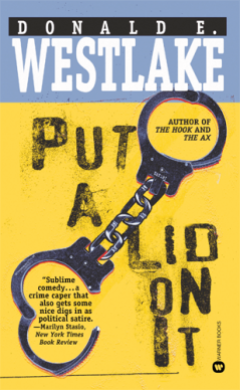

Parker makes a good point. I spent all of Part 1 of this review on Part One of this novel. Part 2 has to cover Parts Two, Three, and Four. Let’s get back to work.

Westlake started writing this book with the idea that it would be about Parker going to prison, escaping, and then doing a quick heist near the prison before heading back to New Jersey. Now just that bare bones concept suggests a daunting array of technical challenges–how to get Parker out of prison, how to execute the heist, how to get him through the police dragnet.

But then came an even more daunting challenge, in the form of Lyme Disease, perhaps picked up while walking near his rural upstate New York home. Westlake managed to keep typing until he’d gotten Parker out, and then went to the hospital for four days; couldn’t work for six weeks after he got out of the hospital. Westlake was almost 70, and it’s reasonable to assume he hadn’t fully recovered by the time he started writing again. If he ever did.

But as he said later, it was when he reviewed what he’d already written that he realized escape was the overriding theme of the entire book, not just the section dealing with the prison. There are all kinds of prisons in this world that we may have to try and get out of–hospitals, for example. Physical afflictions. Prisons within prisons within prisons (to repurpose Thomas Merton).

So Parker and his ‘friends’ (maybe not quite the right word, and that’s another theme in the book–personal and professional reciprocity, the pros and cons of it, no pun intended but there it is anyway) will have to break out again and again, before they win free of this morass, and live to heist another day.

We pick up in Part Two, right after Parker, Brandon Williams, and Tom Marcantoni, have escaped the previously escape-proof Stoneveldt Prison, with the help of Ed Mackey, and some of Marcantoni’s criminal colleagues. They drive to an isolated area by a lake to change clothes, and take stock. Parker and Williams gave Marcantoni their promise they’d help him and his buddies out with a heist in the nearby midwestern city Williams and Marcantoni both hail from.

This is the multi-POV part of the book, where we get to know some of the players other than Parker. We start off with Williams, who enjoys the distinction of being the first African American POV character to appear in a Parker novel (not the first black POV character by a long shot; see The Black Ice Score). He’s reacting about the way you’d expect a black man to react when surrounded by strange white men, all of whom are capable of violence and not much for PC. He’s wondering if he’s going to be alive much longer.

He’s also noticing that the man he knew as Kasper is being referred to as Parker. Even though he’s been a heistman for much of his adult life, he’s still the fish out of water here, but there are reasons Parker, one of the best talent scouts in his field, picked him for the escape crew, and we learn a bit about how he came to be the man he is.

Brandon Williams had grown used to this level of tension, never knowing exactly how to react to the people around him, who and what to watch out for, where it was safe to put a foot. Part of it was skin color, but the rest was the life he’d lived, usually on the bent. He’d had square jobs, but they’d never lasted. He’d always known the jobs were beneath him, that he was the smartest man on the job site or the factory floor, but that it didn’t matter how smart he was, or how much he knew, or the different things he’d read. The knowledge would make him arrogant and angry, and sooner or later there’d be a fight, or he’d be fired.

The people he mostly got along with were, like him, on the wrong side of the law. It wasn’t that they were smart, most of them, but that they kept to themselves. He got along with people who kept to themselves; that way, he could keep to himself, too.

I’d say Williams is a somewhat overdue homage to all the black men who’d written fan letters to Westlake (as Stark) after the Parker novels started coming out–not necessarily felons (though a lot of Stark readers were, and are), but all of them feeling alienated from society, at odds with it, and liking Parker so much because they knew he’d understand their problems, if not necessarily give a damn about them. Not reacting to Parker as a white man, but just as somebody who knew the score, and cared no more about color than blood type. And we all bleed red.

So Williams doesn’t trust any of these people, but he needs them, and as long as they need him too, it’s all cool. He doesn’t like having to pull a job right out of the joint any more than Parker does, but that was Marcantoni’s price for coming in with them. Macontoni’s crew do have a good base of operations, at an abandoned building that used to be a beer distributor.

Next chapter is Marcantoni’s, and it’s where we learn about what the heist is–a jewelry wholesaler. But in a most unusual location. Back around the Mid-19th century, a huge brick armory was constructed in the town, of the type Americans are well familiar with. Municipalities all over the country are still looking for something to do with these white elephants, built like fortresses because that’s what they were, now that most of them are no longer needed for their original purpose. Williams remembers when they used this one for track and field, but that didn’t last.

(Up top, you can see a picture of the Kingsbridge Armory in the Bronx, an exceptionally fine example of the general architectural form; built in 1910, and New York is still looking for something useful to do with it.)

The city finally gave up on the place, sold it to developers, who turned the upper levels into expensive condos. But the ground floor was a problem, because it really had been built to repel invaders (‘like if the Indians had tanks’ Marcantoni snarkily observes). Very thick walls, very narrow windows. Who wants a place like that? Somebody with something valuable to protect, but no need to bring in customers off the street.

Marcantoni, needing a job after his parole, got hired to work on the reconstruction project. And he found out something really neat (seriously, if I found this, I’d want to pull a heist too). The original builders put in a secret tunnel in case the defenders, (perhaps under siege from Lakota warriors armed with medieval trebuchets) needed to escape. Not in the official plans, completely forgotten about. And the other end of the tunnel is in the old library building across the street.

Williams, smartest man in the room as usual (with one possible exception), has some concerns about the structural stability of a 150 year old tunnel, but here’s the problem. Marcantoni is in love with this job. He can’t see past it. He’s waited a long time to pull it (so nobody would remember he was on the reconstruction crew). It’s the main reason he escaped. He knows he needs a big crew to deal with the logistical problems, and he doesn’t mind splitting the very substantial proceeds six ways. He will take it very personally if Parker and his friends don’t live up to their end of the agreement. It’s agreed they’ll do it Sunday. Nobody much feels like waiting around.

Chapter 3 is from the perspective of Goody, a lowlife Williams has the misfortune to be acquainted with. He’s heard about the escape. He knows Williams’ sister, about the only person on earth Williams is close to. He goes to see her, and says if her brother gets in touch, let him know, maybe he could help. Help himself to a nice fat reward, is what he’s thinking. Like so many a minor Stark POV character, he’s not nearly as smart as he thinks he is, and before long his plans come to naught, but he will figure into the plot later, so worth mentioning.

And then we’re at an exercise class inside the armory, and who should we see but Brenda Mackey, attending an exercise class. She doesn’t need to get in shape, her shape is delightful as always, but she knows her husband Ed is going to rob this place, and she knows sometimes he needs help out of a jam (like that time in New York when he almost died), so she’s there to scout the place out in case she’s needed again. Ed didn’t tell her to do this, but then again, he didn’t tell her not to do it.

(Later, we have another nice raunchy sex scene between the two, just before the heist–reminiscent of the one in Plunder Squad, and Brenda doesn’t seem to speak ersatz Chinese during coitus anymore, but she’s still quite vocal.)

It all goes fine, except Brenda catches the eye of Darlene Johnson-Ross, the woman who owns the studio, and this woman seems bothered by Brenda. In the chapter after that, we find out this woman is having an affair with Henry Freedman, he whose jewelry wholesale business is about to get broken into, and she’s worried this attractive fit young woman taking a class much too easy for her is some kind of detective, or IRS agent, or something. And all Henry is worried about is his wife finding out about Darlene.

Next we meet CID Detective Jason Rembek, who has been charged with recapturing the three escapees from Stoneveldt. He knows most guys who break prison have no plan for what to do once they’re out, so are easily rounded up again. He’s wondering if these three will be more of a challenge. ‘Kasper’ is the one that attracts the most attention from him.

Rembek studied the few pictures he had of Kasper. A hard face, bony, like outcroppings of stone. Hard eyes; if they were the windows of the soul, the shades were drawn.

So. The heist. As happens surprisingly often with Stark, it’s very cleverly written, takes up just one chapter, and is, shall we say, not 100% successful. They go in through the library, as planned. They get into the tunnel, as planned. They shore up the tunnel with folding tables, as planned. They get the jewels as planned. The ancient tunnel, in long-standing disrepair, compromised by street work above, collapses on Marcantoni and his two friends, Angioni and Kolaski, on their way out, very nearly smothering Williams too, except Parker pulls him out by the legs. Not quite exactly as planned.

So they have a fortune in gems and watches. Nobody knows they’re there, no alarms were tripped. But the way the place is set up, and with the tunnel now permanently closed off, there’s no obvious way of exiting this part of the building without alerting security, who will alert the law, and it’s back to prison for all three of them (including Mackey, who wasn’t even in prison–he was just doing Parker a favor here–no good deed, huh?).

Williams wants to thank Parker for pulling him out of that hole, and Parker won’t let him. He didn’t do it for Williams. He did it because once again, he needs a crew to break out of a prison. And this one they walked right into of their own free will. He knew it was a mistake. But he did it anyway. End of Part Two, which is the only part of the book that isn’t about escaping from somewhere.

Part Three is the shortest of the four sections (Part One is the longest). 44 pages of Parker, Mackey, and Williams trying to get out of that armory without getting caught. First thing they have to do is drop the loot. It’s only going to slow them down, and they don’t have a fence for it–that was Marcantoni’s side of things, and the contact info died with him.

I like this part of the book a lot, the desolate desperate lonely feel of it, but there’s not much point in carefully synopsizing it. It’s purely about three guys expert in breaking into places they’re not supposed to be trying to figure out a way to break out of a place they’re not supposed to be before morning, when none of them, of necessity, has ever been in there before, or done any advance scouting (Brenda did, but she isn’t there). That quote up top tells you how it’s going to go. Finding tools, breaking through walls, trying to avoid making too much noise, or setting off any alarms. There are a lot of people living in this place.

They finally get out to where they could make it to the street, but not without passing the doorman for the apartments. They need a distraction for him. Mackey has a brainstorm. They’re in an office. There’s a yellow pages. There’s a phone. He finds an all-night pizza place. He orders a pie. Pepperoni, if you’re curious. The guard goes to let the delivery guy in. They get to the stairwell–but the stairs only go up. Not down to the parking garage, where they wanted to go. An interesting exchange follows.

Parker said, “It’s the goddam security in this place. They don’t want anybody in or out except past that doorman.”

“Well,” Mackey said, “that’s what people want nowadays, that sense of safety.”

Williams said, “Bullshit. There’s no such thing as safety.”

“You’re right,” Mackey told him. “But they don’t know that.”

We still don’t.

So they finally get to where they can get out to the street, but now they have a new problem. Donald Westlake was a born problem solver, and this is the kind of problem he can truly relate to. The physical challenges, but also the strategic ones. They need more than just a means of egress–they need a means of escape, transportation, so they’re not trapped on the empty streets outside, just waiting around for the law to scoop them up.

Mackey figures they can call Brenda–she can come pick them up. Except none of them has a cellphone. They have to go back into the trap, break into another office, use the phone there. And then it turns out Brenda’s motel room phone is set not to receive calls until tomorrow morning. And she doesn’t have a cellphone either. They need somebody to come get them. Williams has a really dangerous idea.

Goody. Williams knows, for a stone fact, that Goody wants to sell him to the law. But he also knows Goody is stupid and greedy enough to come get him. He and Parker work it out–set up a meet at a camera store across the street. He’ll say he wants Goody to drop him in a little town nearby, where some relatives live, and he can hide out with them. Goody will figure he can bring him there, then call the law on him–low risk, high reward, except Goody doesn’t know about Parker and Mackey. They’ll just take the car and go.

(All three are heeled. Parker has his usual go-to, the five shot Smith & Wesson Terrier .32 snubnose. Now I’ll quibble, very briefly. We’re told back in Part Two that Mackey has a Beretta Jaguar .22–we’re told he equipped Parker and Williams similarly. Then we’re told in Part Three that Parker has a Terrier. Let’s do a side-by-side comparison, shall we?

Okay, they’re both small handguns. Other than that, not terribly similar. And this is easily explained by Mackey knowing Parker’s tastes in armament. And it still bothers me. And this is why authors of crime fiction should think twice about getting specific on guns.)

Now what I left out of the Part Two synopsis is that Goody, who is a smalltime drug dealer, ran into problems with his supplier, who is a bit less small-time, and who had his men do things to Goody until he told them about the reward money he planned to get for Williams. They’re going to come along and make sure they get their share.

So things get a bit confusing once they run out there to Goody’s black Mercury, and all of a sudden there’s a Land Rover pulling up, and three men with guns jump out. Parker quickly figures the guy in the back of the Land Rover as the boss, drops him, and the other two are nothing without their brain. Williams gives his old pal in the Merc a proper thank you for his loyalty. So they end up driving away in the Land Rover, Williams at the wheel, the four interlopers left behind with bullet holes in them, and that’s the end of that subplot. Goody.

Except a lot of gunfire in the street was never the ideal version of their plan. There’s jumpy security-obsessed rich people calling the police in those fancy apartments up above. They figure on ditching the Land Rover for a car Mackey has stashed nearby. There’s a lot of maneuvering through a parking garage they take refuge in, and let’s just skip over that part. “All I want,” Williams said, “is to be in a place I’m not trying to get out of.” You said a mouthful, brother.

They get to where Mackey stashed a Honda, and it’s still too soon to contact Brenda–who has a car of her own. So they offer Williams the Honda so he can get over the state line, start over. He’s touched. He gets the hell out of there before they can change their minds. Strange strange white people. They get some sleep, but then Mackey wakes Parker up. Brenda has been arrested. They have to break her out of jail.

Hey, maybe now would be the time for a little musical interlude, what do you say? I posted an image of a watchtower in Part 1. Here’s the song to go with it.

(I could have gone with Dylan, but you know, The Experience was two ofays and a brother as well. Though this power trio we’re looking at is maybe a bit more even in the talent department.)

Part Four is less focused, more freewheeling. Lots of ground to cover. Parker comes downstairs, and finds Mackey and Williams sitting at the table. Williams was supposed to be headed for the border, but just when he thought he was out, he pulls himself back in. He heard about Brenda’s arrest on the radio, figured Parker and Mackey might need a hand. This is the first thing he’s done in the book to lower Parker’s opinion of him.

The radio provided Williams with a lot of information. The cops found Marcantoni and the others in the rubble, dead of course. They figure Parker and Williams were involved too. Brenda got arrested by doing what she always does–hanging around nearby when Mackey is doing a job, in case he needs her to rescue him. Like she did that time in New York, which is how Mackey is still alive, but without cellphones, there was no practical way she could help out, and that woman from the dance studio saw her hanging around and called the police. They figure she’s the brains of the outfit. Which might be true if it was just her and Ed.

They have her in a city lock-up. Williams knows the place. Not as tough as Stoneveldt, but tough. Ed’s all for going in. Williams is dubious, but game.

Parker wants no part of this. It’s long past time for him to get out of this hick town, like he should have done to start with. Ed senses his reluctance, is angered by it. Please remember, not only did Brenda save Ed’s life once–she’s the one who made Ed stick around and wait for Parker after that heist they pulled in Comeback. Ed helped him break prison just now, stood by him on a heist that clearly wasn’t planned out properly, just out of loyalty. If Parker owes anybody in this world, he owes Brenda and Ed Mackey. But in his mind, he doesn’t owe anyone anything. Parker didn’t live by debts accumulated and paid off; is what the narrator tersely informs us.

Excuse me? Mr. Stark? Have you forgotten every previous book in this series? ‘Debts accumulated and paid off ‘is basically all Parker lives by, starting with the debts he collected from his wife, and his former partner, and an entire criminal syndicate, in the very first of those books. Debts Accumulated And Paid Off might as well be the epitaph on his tombstone, assuming he gets one. Parker has risked himself far more seriously than this to pay off a blood debt to somebody who wronged him. He’s also risked himself several times to help criminal associates like Handy McKay and Alan Grofield, though there were other factors involved besides loyalty each time.

You can, if you want, explain this away. Parker comes after people who wrong him in some way because their treachery triggered a response he has no control over, and he needs to kill them to restore his mental equilibrium. He helps fellow heisters he’s working a job with because that’s part of his professional ethic, and because he might need to work with them again someday–in this case, the job was over as soon as they got out of the armory.

He tells himself he’ll have to help Ed and Brenda now, because otherwise if he and Ed work together again someday, Ed won’t trust him anymore–but seeing as we never see him work with Ed again in the series, and he’s got a lot of other names stored away in his head, that doesn’t seem like enough of a reason.

It’s a much bigger motivational problem than the one in The Jugger, that bothered Westlake so much, and Westlake should have seen that. If Parker isn’t helping the Mackeys out of professional solidarity, or out of a sense of obligation for what they’ve done for him–as Williams, a near-stranger is willing to do, just because Ed let him have the Honda–why the hell is he doing it?

Because Stark can’t let him do anything else. Stark can’t ever let Parker appear ignoble. But neither can Stark allow his pragmatic anti-hero any virtuous motives. And usually that works out fine. And this time, it feels a mite forced. As if Westlake, still hollowed out by his recent illness, couldn’t fully access that part of himself that could interpret Parker’s thoughts for us. I had only read two previous Parker novels when I first got to this one. I already knew it was wrong to say Parker doesn’t live by debts accumulated and paid off. But how else would you say it?

But in critiquing the way Stark does it here, I still appreciate what an important question is being asked. No matter how independent you are, you are still going to need help sometimes. In order to reliably receive help, you will need to offer it in return. Was Brenda right when she pulled Ed out of that burning lumberyard, but wrong when she was waiting around outside the armory to see if he needed her again? How could she ever know for sure? How can you know when you’ve crossed the line between legitimate obligations and sucker bets? And isn’t there anything in this world besides debts accumulated and paid off?

Ed doesn’t care if he owes Brenda or not, because he loves her (he never says it, and he doesn’t need to). If he walked away from her now, he’d be nothing. (Parker would never walk away from Claire either, of course, because she’s a part of him). Williams just wants to respect himself in the morning–to feel like the man he was born to be, that society wouldn’t let him be in any other walk of life. Parker and Mackey see that man when they look at him, and that’s why he came back.

Parker feels none of this, for any of them. But he’s caught in a web of conflicting obligations (my Celtic ancestors used to call them geasa and they’ve killed no end of tough guys). Another kind of prison. Ed’s sense of obligation to him was a necessary factor in his escape from the actual prison he ended up in because of a confederate who acted as if his only obligation was to himself. There’s no solution to this equation. You just have to decide what feels right to you, and accept the consequences. And never know if you’ve chosen correctly until it’s too late to do anything about it.

Ultimately the only answer to this conundrum is that Stark is a romantic, and Parker isn’t. Let’s get back to the synopsis.

As romantic as it unquestionably would be to shoot their way into the jail, like the 1920’s heisters, or the Old West outlaws, Parker has a less sanguinary plan. He still has the card for the criminal attorney Claire got him. A very capable shyster, Mr. Jonathan Li. And if they can just get Brenda released on her own recognizance, the charges against her dropped, she can go on living in the straight world, instead of being a fugitive like Parker and Ed.

Li knows he is now dealing with fugitives from the law, and as long as they don’t implicate him, and the check doesn’t bounce (or hell, just send cash), he’s got zero problems with helping them. The problem lies with Darlene Johnson-Ross. She’s the one who spotted Brenda waiting in the car, recognized her blonde hair, called the law. (I don’t accept Brenda is a blonde, it’s never been mentioned before now, but we can talk about that in the comments section.)

If this woman dropped her complaint, they’d have nothing to hold Brenda on, and Li could do the rest in his sleep. But she has to drop it. She can’t just disappear, conveniently and forever, or Brenda will be held on suspicion of conspiracy to commit murder. Li knows who he’s talking to here, never doubt it.

What follows is probably my least favorite part of the book, that involves finding Johnson-Ross at her house, with her lover (the guy they almost robbed), and using a variety of threats (none of them terribly veiled) to convince her to go tell the police she made a mistake, and this is definitely not the same dame. If she doesn’t, then they’ll kill her boyfriend. It’s a bit hard to understand why she cares, given that he’s possibly more terrified of his wife finding out about them than he is of these three desperate criminals with guns, but who can explain it, who can tell you why, fools give you reasons, Freedman doesn’t die. Turns out he makes really nice sandwiches, and Ed figures you don’t shoot a guy who feeds you.

This is the last prison they find themselves in, unable to leave her house until they know Brenda is out, wondering if the police will come by and check, which they do, but not seriously. Williams makes his exit (in Freedman’s Infiniti) before they find out what happens, because seriously, he’s done his share and then some. They never would have even found the house without somebody who knows the area.

(It’s a bit too cute, this part. Too Dortmunder-esque, except you know that these guys actually can kill people. Mackey is his usual jocular self, even helps Darlene with the dishes. Freedman gets Stockholm Syndrome, starts identifying with his captors. I’m not saying it couldn’t happen, it’s just a bit much that we spend more time on this hostage caper than on the robbery. Well, anything for Brenda.)

Endgame. Brenda’s been released, Li worked his magic. She’s taking a cab to the airport. Ed will rendezvous with her there–the cops don’t know his face. They’ll get the car they have in long-term parking, and drive out of state. Of course the law is tailing her. Parker can’t go with them. He’s going to need another ride.

And who should he spot in a remote area of the airport but Detective Turley–you know, the one who talked about game theory so much. They’ll get to talk about that some more. Parker commandeers Turley and his vehicle. Turley’s a pro, and he knows by this time Parker is no less professional on his side of the law. He wants to live to type up his report. So he gets them past security, and they get the hell out of Dodge.

Bit of driving to do now. Might as well chat to pass the time. Turley mentions that even though he’s a state cop, the car they’re in belongs to the local police. A few years back, there was a proposal floated to the city government–equip all the squad cars with location devices–so that if a car went missing, they could find it. You know what the city fathers said? “You boys are local law enforcement, you know exactly where you are.” Turley’s having a good chuckle about that now. Parker is less amused. He’d probably have had to kill Turley and find another car if they’d shelled out for that tech. Turley’s not done gabbing, and Parker knows why.

Just as Parker had known what Turley was doing underneath his words back in Stoneveldt, he understood now what this cosy chat was all about. Turley was a good cop, but he was also mortal. His second job, if he could do it, was to bring Parker in, but his first job was to keep himself alive. Talk with a man, exchange confidences with him, he’s less likely to pull the trigger if and when the time comes. Like Mackey deciding to do it the more difficult way because Henry had made him lunch.

This wouldn’t work on Parker, but he doesn’t need Turley dead. There’s a railroad town coming up. Also a major truck stop. He leaves Turley by the roadside, in the middle of nowhere, throwing his gun into a cornfield where he’ll take some time finding it (but won’t be humiliated by Parker having taken it away from him). Parker ditches the police Plymouth, and looks for his ride out of this goddam flat state.

He has a pretty good idea of what he’s looking for, or rather, whom. A couple in their 40’s or 50’s, who own and operate a big rig together. More and more of those on the road now–must have been a fairly new trend back when this book was written. (Parker, like his creator, never stops watching people–you never know what bit of information will come in handy). They’ll invite him aboard just to have somebody to talk to, chat on the porch, so to speak. A lone trucker wouldn’t want to risk it. A couple seeks out company, to spice up their own relationship.

Then here they came. He knew they were right the instant they walked out of the cafe. Mid fifties, both overweight from sitting in the truck all the time, dressed alike in boots and jeans and windbreakers and black cowboy hats, they were obviously comfortable together, happy, telling each other stories. Parker rose and walked toward them, and they stopped, grinning at him, as though they’d expected him.

They had. “I knew it,” the man said, and said to his wife, “Didn’t I tell you?”

“Well, it was pretty obvious,” she said.

Parker said, “You know I want a lift.”

Marty and Gail. Quite possibly the nicest people Parker’s ever met, which I suppose isn’t the highest praise that can be given, but they’re pretty darn nice. They can get him as far as Baltimore. He says he could walk home from Baltimore. They’ve got a Sterling Aero Bullet Plus. Probably not unlike this one. Don’t really know much about trucks. I do know the drivers matter more than the trucks do. At least until it’s all done with computers and GPS. Watch your backs, Martys & Gails of the world. Google Trucks is coming for you.

Parker has a good story to tell them about how he lost his car and his money in Vegas, and there was a woman involved. He doesn’t get into detail much about it. They can fill in the blanks themselves. All they know is that he’s headed for New Jersey. Well, that’s all they know officially, put it that way. Marty in particular knows more than he’s saying.

There’s a police roadblock coming up. Marty tells Parker he doesn’t feel like dealing with it, so he’s going to take the scenic route, on the side roads. Get back on the highway once they’re past the cops. And he’s got a little story of his own to tell Parker. He did time once. Attempted robbery. Served four years, which was the minimum.

“Four years is a long minimum,” Parker said.

“Oh, you know it.” Marty concentrated on the road awhile, then said, “I know there’s fellas belong in there, I know there’s fellas I’d prefer was in there, but after being in there myself I could never put a man in a cage, personally. Never.”

“I know the feeling,” Parker said.

“If a man wants to learn from his mistakes, fine,” Marty said. “You look at me. You see the job I gave myself. Coast-to-coast hauling. You can’t get much farther from a four-man cage inside a six-hundred-man cage inside a four-thousand-man cage.”

Prisons within prisons within prisons. But there’s always a way out, if you look hard enough. And there’s people who’ll help you, if you ask. The decent people of this earth. The sane ones. They do exist.

But Parker, I’m just wondering–what if things turned out so that you had to kill these good people, who are helping you for no reason at all other than that they feel like it? What if that was the only way you could stay free? Would you do it? Could you? I’m asking a question, Parker. Answer me, damn you. Silence. That figures.

They pass the roadblock, and Marty says the state troopers are just doing what they were told. “They aren’t hunters. They’re just boys doing a job.” Maybe he knows what’s sitting next to him in the cab, while his wife sleeps peacefully in back. Maybe not. We don’t see Parker say goodbye to them. Which means we don’t know if they were still alive when he left them–knowing what they do about him, where he came from, where he was headed. We don’t even get that much of an answer to my question. But Parker doesn’t kill when he doesn’t need to. That I know. He’s not one of us.

And Chapter 17 of Part Four is so short, I can type the whole damn thing. Why not?

Claire rolled over when he walked into the room. Her eyes gleamed in the darkness, but she didn’t say anything as she watched him move. Out of his pocket and onto the dresser went the three Patek watches that were the only result of the jewel job. He stripped and got into bed and then, folding into his arms, she said, “Gone a long time.”

“It felt like a long time.”

“I knew you’d be back,” she said.

“This time,” he said.

Just FYI, some Patek Phillipe & Co. watches sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars–some can even cost millions. Probably a midwest wholesaler wouldn’t have the top of the line models, but Parker would have picked the best of the bunch available, and he can find a fence for three watches easily enough. He really does not like to walk away empty-handed from a job. Neither did Donald E. Westlake.

What I walk away from this book with is a sense that the walls are starting to close in on Parker, in a way we haven’t seen before. Yes, he got away, but the law caught him, photographed his new face, connected it to his old fingerprints. He’s got a few more killings to his official credit, not that he needed any more to go away for life. He’s still having a harder and harder time finding jobs he can pull in this strange new world of electronic cash, electronic surveillance, ever-faster information sharing between far-flung police departments.

He still has to work with unreliable people sometimes, which creates points of vulnerability–and when he works with people he can trust, because they trust him, that creates other points of vulnerability, perhaps even more dangerous.

He’s free, but it’s not unqualified freedom, liberty without caveats. I suppose there’s no such thing. He’s certainly got a wider range of amenities in that house, with Claire (a fine amenity in herself). But he has to keep paying for them. He has to keep hunting, like any predator. And sooner or later, every predator becomes the prey. Nobody runs forever. Yes, this is foreshadowing. Three more books left. Which can, arguably, be seen as one long book. Or one multi-faceted work of art.

The next Parker novel was published two years after this one, and by all rights, I should get to it in a few more weeks. But I’m going to break with my usual habit of reviewing books in the order in which they were published. Two rather unsatisfying standalone books are next, neither of them books Westlake will be remembered for, though both with things to recommend them. Then a whole lot of Dortmunder: novels, novellas, short stories, workout routines.

And then we’ll get to the defacto conclusion of the Parker Saga, along with the very last Dortmunder, and the very last Westlake novel ever to be published. The end, in fact, of the primary literary oeuvre of Donald E. Westlake, hard and painful as that is to believe. And by extension, the end of my needing to publish an article here every week or so. One prison I’m feeling rather ambiguous about breaking out of. But there’s always another one waiting outside. Right?