Until recently, when he visualized that destruction, the image in Curtis’s mind of the toppling skyscrapers was immediately supplanted by the image of the ancient bastards in Beijing, the shock and the fear on those age-lined pig-faces when they heard the news: someone has killed your golden goose. The image of those faces had been enough for him, could bring him a smile every time he thought of it.

But just in the last few days, he’d found himself, not willingly, thinking about the people inside the buildings. There would be no warning, merely a low rumble in the earth and then the buildings would go over like chainsawed trees. No escape.

Those people in the buildings weren’t his enemies. But he wasn’t going to worry about them. They’d made their choice when they’d decided to stay, after the bastards from the mainland took over. They could have gone away, almost every one of them could have gone away. They could have gone to Macao, or Malaysia; many could have gone to Singapore (as Curtis had), or Canada, or a dozen other places in the world. But they chose to stay, so what happened was on their own heads.

Still, now that he was thinking about it, it seemed to him, for a number of reasons, he would be better to make it happen at night. He’d always visualized it in daylight, in bright sun, the gleaming glass buildings as they went over, but that wasn’t necessary. He certainly wouldn’t be there to see it.

At night, it would be easier to make the collections.

It’s been months since this book, the last ‘new’ novel we’ll ever see from Westlake, was released. Time for me to review it properly, as so few of his novels ever have been, which is why this blog exists. To discuss, and in some detail, character, motivation, subtext, influences, style. And plot. If you read this whole review, you’re going to know the whole story. Shall we proceed? Open your sealed dossiers, and let the debriefing begin. (Oh get your minds out of the gutter, it isn’t that whole a story).

There have, to be sure, been many reviews out there–you can see quotes from them on Amazon, including a blurb plucked from my own non-review review of some months back (mildly disorienting for me to read there, but I’ll take it). Generally sketchy, sometimes insightful, mainly positive. Not all from Westlake fans, either.

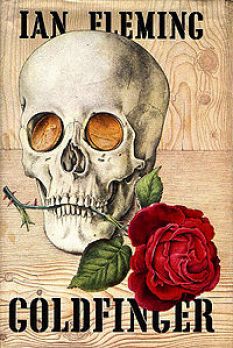

Reader reviews have been more mixed. The general gist seems to be “Not bad, but I thought this was a Bond novel. Where’s Bond?” He ain’t here. Not out there in reality, either. That’s the point of the book, I argued back then (in my blurb), and I stick to that.

There are real villains, in the real world, with real evil plans, and the very real power to carry them out, and they do. There is, however, no handsome heroic multi-talented individual who can more or less single-handedly foil these villains. That kind of story is fun to read, and to watch, but it’s not real, even if you cut out the cloak and dagger stuff. (Edward Snowden? Remind me who’s paying his rent now? More of an unwitting henchman. With Assange, you can cut out the unwitting part.)

Now of course Bond was never entirely on his own, he always had allies, collaborators, an entire government apparatus behind him, but the Fleming novels, and the films inspired by them, are still celebrations of rugged individualism, even as they depict an organization man, someone of whom it can honestly be said (to borrow a phrase from a much better written spy series) They’ve given you a number and taken away your name.

Spies are real, no question about that. They’re all around us, much more than we realize. And their work is typically less glamorous and exciting than that of a bike messenger for a Wall St. firm. More dangerous, perhaps, but that depends on where they’re doing it, and when. They get information. They convey it to their paymasters. There may be a certain limited measure of kiss-kissing and bang-banging, but not much, if they’re doing the job right. Flash does not pay in their business.

But it’s what you’re selling with a Bond novel, a flight of pure fancy, which this book serves as a more earthbound commentary upon. It’s written in a genre that might roughly be slotted as ‘suspense/thriller’–it’s no kind of spy novel. There are no spies in it (well, there is one–a minor character, and an amateur–you know what tends to happen to them in Westlake novels). No government espionage agency, real or imaginary, is involved, or even referred to.

This was a deliberate choice. Westlake could not legally publish a novel with James Bond as the protagonist, but let’s remember that the people who control the 007 franchise don’t own the idea of manly secret agents battling baddies while bedding babes, which Ian Fleming did not invent, and couldn’t have copyrighted if he had. Matt Helm, Derek Flint, and Austin Powers all attest to this precise type of story being in the public domain.

This could easily have been a novel about some freelance tough guy getting sucked into a Bondian scenario–Westlake had done that before, though more often as Richard Stark–Parker had been a sort of spy in The Handle, if without much conviction (that book gets a bit of a shout-out here). Alan Grofield had been dragooned into the role of secret agent in The Blackbird. Under his own name, Westlake had sent up the entire genre with The Spy in the Ointment.

These are all more economical, less ambitious books than the one we’re looking at, and much better ones, written in his two strongest authorial voices. For us to properly evaluate this book, we have to accept he wanted to try a new voice, a new approach, incorporating elements of what he’d done before into new settings, with characters you’d never want to try and build a series of books around, who are much more mundane and ordinary than characters in this type of story tend to be. Because they’re standing in for us.

Westlake wanted both his villain and those opposing him to be unaffiliated, and he also wanted them to be newbs, unaccustomed to their roles, though each has applicable skills, if they can figure out how to apply them. There are cops involved, and robbers, but mainly ancillary. The characters who carry the action are a commercial developer, an engineer, a smuggler, a construction foreman, and three environmental activists of radically different backgrounds. This is not to say they are the only characters who matter, because the point of the book is that everybody matters. Everybody makes a difference. For better or worse. Sometimes both.

This is a story about a man attempting to murder an entire city, for revenge and profit, a few dangerous pawns who assist him for reasons of their own, and a few decent brave flawed individuals, who come to realize by degrees what he’s attempting, and try to stop him. It’s a detective novel, as much as anything else. But written quite frequently from the criminal’s POV–a Westlake specialty. So also a heist novel. As are some of the Bond stories, most notably Goldfinger, probably the one Westlake was most familiar with, since he tried his own take on a military base heist in The Green Eagle Score, which I’d take over all the Ian Fleming books ever written, with the pastiches thrown in.

To sum up how all this happened, for those arriving late, Westlake was tasked with writing a story treatment for the Bond film that was going to follow Goldeneye, assuming Goldeneye wasn’t a flop. He asked Jeff Kleeman to send him videocopies of some of the Bond films, making it clear he hadn’t seen them all. Unknown which if any of the Fleming books he’d read.

I don’t know if one of the films he viewed in preparation was A View To A Kill, which I very much doubt Westlake went to see when it came out, and had not been greeted with much enthusiasm at the time. Christopher Walken’s diabolic Zorin, a giggling over-the-top Nazi science project of a man, has an idea quite similar to that of the baddie in Westlake’s original treatment, relating to Silicon Valley (an idea that could not possibly work in reality, for reasons Westlake would have immediately perceived, but what else is new in Bond-town?)

Since Zorin’s plan was self-evidently inspired by Goldfinger, maybe Westlake never saw the later film at all, and was just extrapolating along comparable lines? Westlake liked to avoid obvious repetition when possible. (But then, isn’t obvious repetition part and parcel of this franchise?)

Greg Tulonen, Phil P., and Jeff Kleeman (in his engagingly informative afterword to this book), have all helped us better understand how this project came to pass, and why Westlake’s treatment ultimately went nowhere, became something else, written by somebody else, with just a few of Westlake’s ideas marginally present.

He then felt moved to write a very long novel (610 pages in the original manuscript) that took the core ideas from his treatment and made a new story out of them, which met with a muted response from people whose opinions he valued, so the book was put aside, while still in early draft form.

But we’ve covered all that already. What we’re looking at is the book that has now been published, boiled down to a more manageable length by Charles Ardai. And our mission, should we choose to accept it (I know, wrong franchise), is deciding whether we can view it as any kind of success on its own terms, or simply an oddity, a forgotten relic from the career of a storied storyteller.

Our mission is complicated by the fact that the book was never properly finished. This posthumously edited version differs in many respects from what we’d be reading if Westlake had gotten it published in his lifetime. There would have been more drafts, editorial notes, sharpening of character, tightening of story, tweaking of language. All Ardai could do was what Abby Westlake reportedly suggested her husband do back then, namely that he ‘cut a hundred pages of hemming and hawing.’ (That’s how Westlake himself put it, perhaps Abby was more diplomatic.)

It wouldn’t rank among his best books, no matter how long he worked on it, because this type of material was never his strongest suit, and it was a bit late in the day for such a radical reinvention. I wouldn’t call it one of his worst books, because there is a sense of energy and purpose to it, for all the missteps and rough patches–much better than Who Stole Sassi Manoon?, or Gangway!, both of which had comparable Tinseltown origins. Not sure I’d call it a Westlake, either.

As I said, when I wrote about it some months ago, it strikes me as being written more in the style of Timothy J. Culver, the portion of Westlake’s psyche that wrote very long ‘airport’ novels of intrigue and adventure, with humor on the down-low. Only Ex Officio was ever published under Culver’s name, and Westlake wrote disparagingly of this alter ego, but Kahawa, to a lesser extent, is written in that mode, as is Humans. None of these books were big sellers, though Kahawa was critically well-regarded, has a loyal following to this day, and is in most respects superior to Forever And A Death.

Westlake reportedly wanted this one published under a feminine nom de plume, something Knox Burger, his agent of the time, found disconcerting. It’s not clear why he was so bothered, since Westlake’s very successful friend, Lawrence Block, has written on and off as Jill Emerson for over half a century now. Maybe it was something else about the name that bothered Mr. Burger, who would be thinking about how this book would impact the Westlake ‘brand’. (And of course no matter what name it was published under, it would be outed as his handiwork, sooner or later–plenty of hints for the sharp-eyed).

Westlake had, interestingly, published four detective novels under the name Samuel Holt–same name as the protagonist/narrator of that series–and Burger specifically cites the Holt novels in his response to Westlake, not at all in a complimentary fashion. Was his suggested pseudonym here also the name of a character from this book? Somebody out there must know, but I don’t.

I do know I better start the synopsis–this is a good-sized novel, divided into four parts, each primarily set in a different location, with many a twist and turn along the way, involving at least 13 POV characters (the precise number is debatable). I don’t intend to let this turn into a three or four parter, as I have in the case with shorter books with more fine detail work.

My intent is to make Part 1 about Parts One and Two, and Part 2 will be devoted to Parts Three and Four. For all the POV characters in this book, there is one who looms above all the others. And he’s not the hero. But in his mind, he’s the–

ONE:

He was consumed with so much anger, so much hatred, that he found it hard to be around other people for very long. The snarl beneath the surface kept wanting to break through.

And of course, everybody knew about it, which only made things worse. Everybody knew they’d driven Richard Curtis out of Hong Kong, those mainland bastards, once they’d taken over. Everybody knew they’d cheated him, and robbed him, and driven him out of his home, his industry, his life. Everybody knew Richard Curtis’s great humiliation. But what nobody knew was that the game wasn’t over.

This story begins and ends with Richard Curtis–a name I feel confident in saying is derived from Westlake’s two hardest-boiled pseudonyms–Richard Stark and Curt Clark. Because Richard Stark wrote The Score, the premise of which hangs upon a man with a blood vendetta against the town that exiled him, and is using the professional heist men he’s working with, Parker included, to get his revenge.

Curt Clark wrote Anarchaos, a science fiction noir about a man possessed by rage against society, who sets out to learn if an entire planet of criminals murdered his brother, and pass sentence if it has.

Curtis’ ambitions lie somewhere between those two poles. As does his morality, if he can be said to have any. His identity crisis lies in the fact that in order to try and regain the person he used to be, he’s got to become what he never was before–a killer. And we should remember, Westlake wrote this not long after he wrote The Ax. But all these books I mention were much more focused.

This story is going to be more divided in its attentions, and its sympathies. A strength and a weakness. A challenging story to write, all the more since it’s using a borrowed template that needs to be subtly altered to get Westlake’s points across–Curtis is a rationalized Bond villain, with a rationalized Bond villain scheme, rationalized murderous henchmen with inner lives of their own, and more believable motivations than any villain I can think of from the Fleming novels, or the many films based on them.

The people who come to oppose him are, in a sense, a collective 007, standing in for we the audience. Also rationalized, and fallible as all hell, forced willy-nilly into the role of hero, finding it not nearly as much fun as the movies make it seem. Fascinating concept. Incredibly difficult to execute properly.

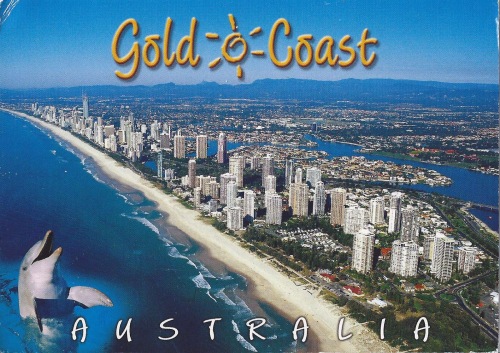

We see a helicopter coming in to land, on Curtis’s yacht, at sea, off the coast of a small abandoned atoll, a former Japanese military base, under the territorial authority of Australia. Curtis is on that helicopter. He’s come to see a dream made real. Not necessarily a pleasant dream.

Working with a brilliant young engineer, Richard Manville, Curtis intends to use a soliton wave, created by carefully set explosives, to turn the entire island to mud in a matter of minutes. Thus creating a blank slate upon which he can build a luxury casino resort, his very own Cockaigne, though the name is never mentioned–Westlake drawing a sly subtextual parallel between Curtis and his earlier attempt at a Bond-style villain, Baron Wolfgang Friedrich Kastelbern von Altstein, who likewise made a paradise of vice out of a desert isle.

Though Curtis is genuinely interested in this project, its potential for long-term profit, what he’s allowed no one to know is how desperately he requires a massive influx of capital, that no legitimate enterprise could ever yield him in time. As matters stand, each of his partners in the venture thinks Curtis has secretly sold him/her a bigger share than the others, and Curtis’s own share is accordingly diminished. Scratch a capitalist, find a con artist.

He was a billionaire developer in Hong Kong, until the mainland Chinese government took over there, and forced him out, helping themselves to most of his assets in the process. This wholly predictable turn of events hurt him far worse than it should have–he was too stubborn and self-willed to cut his losses and relocate to Shanghai. A tiger fighting a dragon, doomed from the start. He only surrendered to the inevitable once he had no other choice, and too much damage had been done for his fortunes to recover.

Richard Curtis, like many if not most people at the pinnacle of the One Percent, can’t abide any form of authority over him–not even one of the world’s most powerful and autocratic nations. Nor can he ever forgive a slight–let alone a defeat. There is zero chance of his dying in poverty, very little of his ever paying for his chicanery with prison time. That’s not the point. His identity is based on being a billionaire developer, and a billionaire developer he must remain. No matter what.

In the eyes of the world, he’s still all of that, more or less self-made (though he more or less stole his company from the children of those who created it, marrying one of them in the process). He began as nothing more than an oil-rig worker out of Oklahoma, son of a fly-by-night contractor. He is decidedly not an entitled strutting self-promoting media-driven fraud like Trump, though comparisons are there to be made, if you like–most notably in the way he’s over-leveraged himself, owes far more than he owns, and is no more than a few years away from ruin, if he can’t make the kind of score that no one would ever imagine him capable of pulling off. (Yes, there are parallels, I just said so.)

He’s no stranger to cutting legal and ethical corners, never had any qualms over doing so–but now he’s decided to commit mass murder, apolitical terrorism on a scale that would dwarf 9/11 (which hadn’t happened at the time this was written, and please note, a wealthy engineer was behind that as well). All this in order to cover outright theft, of the gold reserves lying in underground vaults there.

But even more important to him, this would deal a vicious blow to the ‘ancient bastards’ in Beijing (another subtextual cross-reference, this time to Humans)–and by extension, the entire world economy. Perhaps millions of lives will end by his hand, billions more will be impacted. What Richard Curtis can’t control, he destroys.

Does he care? Only to the extent that it changes the way he looks at himself. He tells himself that he’ll do it at night, to minimize the number of people present in the business district of Hong Kong, built mainly on landfill, that will crumble the same way as the fragile atoll to the soliton’s kiss. But this is not compassion, or guilt, and he has no capacity for shame. He’s just not yet ready to fully accept what he’s in the process of becoming.

In the meantime, others are going through transitions of their own. As Curtis and Manville prepare their experiment from Curtis’s palatial yacht (Manville has no inkling of what further use Curtis has for his idea), a ship from the environmental group Planetwatch approaches. An expedition led by Jerry Diedrich, who has a long-held mysterious vendetta against Curtis, and has plagued him in the past. He has learned about the soliton through private channels, and is claiming it will damage the Great Barrier Reef. His public statements don’t match his personal motives. Curtis is his own personal Great White Whale, and the reef is just an excuse to throw harpoons at the blowhard’s blowhole.

Aboard the ship with him are various other activists, including Diedrich’s cool enigmatic German-born lover, Luther Rickendorf, made of sterner stuff than the temperamental Diedrich, who won’t come into his own until later in the book.

More important to this part of the story is twenty-three year old Kim Baldur, child of the middle class, American as they come, both a good and a bad thing (and when is it ever not?) The last of Westlake’s perky blonde ingenues, and perhaps the best of them. Brave, impulsive, naive, idealistic, decent, far too trusting for her own good. And like most kids, convinced of her own immortality.

(I finally head-cast her as Michelle Williams. A bit too seasoned to play Kim now–at least the girl she is when we meet her. The woman Kim is by the end, Williams could still play admirably.)

Manville didn’t put in a fail safe device, so once the countdown has started, it can’t be stopped. Diedrich refuses to believe this. Kim, a trained diver with a Norse surname, takes it upon herself to be the sacrificial offering, believing as her mythic namesake did, that nothing in nature could ever harm her.

Without asking anyone’s leave, she launches herself into the ocean, swims for the island, believing this will force them to stop the explosions she has been told will irreparably damage one of the world’s natural wonders. But even the most ardent beliefs can’t change the facts, and Curtis probably wouldn’t give the order if he could. By the time Kim and everyone else realizes what’s happening–

At first, the sea seemed to shrink, to turn a darker gray, as though it had suddenly grown cold, with goosebumps. There was a silence then, a pregnant silence, like the cottony absence of sound just before a thunderstorm. The island seemed to rise slightly from the sea, the concrete collar of its retaining wall standing out crisp and clear, every flaw and hollow in the length of it as vivid as if done in an etching.

Then a ripple appeared, faint at first, and rolled outward from the island, all around, just beneath the surface, like a representation of radio waves. With the ripple came a muttering, a grumbling, as though boulders sheathed in wool were being rolled together in some deep cave. And the ripple came outward, outward, not slacking, not losing power, with more ripples emerging behind it.

Planetwatch III, in too close, nearly capsizes in the backswell, but her captain keeps her afloat. Nobody witnessing any of this believes there’s the slightest chance Kim survived. Manville is deeply troubled, feeling he was responsible for not foreseeing such an eventuality. Diedrich, a good man for all his bombast, is likewise asking himself if he is responsible for this child’s death.

Curtis, to whom other people are assets or liabilities, sees a strategic opening. If he can hang the death of this suicidal fool on Diedrich, he can tie the gadfly up in the Australian courts during the coming critical weeks–otherwise Diedrich might well appear in Hong Kong, since he clearly has a well-placed mole in Curtis’s company. Curtis can’t believe his good fortune.

Not so lucky as he thought. His men, doing the obligatory search for what they assume will be a corpse, find Kim floating unconscious off the coast of the reformed island. There’s a faint pulse in her throat. She’s brought on board, examined by the yacht’s skipper, Captain Zhang, who has some basic medical training. He happily tells a disappointed Curtis that her injuries are not fatal.

The startled captain is then informed by his employer that he is mistaken–Kim Baldur will never wake again. If necessary, Zhang must make sure of that. Believing without question that his none-too-subtle wishes will be carried out, since Zhang is a family man, and depends on Curtis for his present comfortable livelihood, Curtis proceeds to inform his business partners on the yacht, as well as Manville, that the girl died without ever regaining consciousness.

This is a mistake he will come to regret, leading to a cascade of subsidiary mistakes that will force him to go further and further out of his comfort zone, until his criminal enterprise is no longer a dry abstraction to him. Diedrich was far less of a threat than the enemies Curtis is going to make by trying to neutralize all potential opposition–he has no suspicion that Curtis is an aspiring city-killer, nor was he likely to have found out on his own. But his constant harassment got under Curtis’s skin.

Westlake had long made clear his contempt for people who make murder the answer to everything. It is as much a logical as a moral disdain. Killing creates more complications than it resolves. It’s the most unpredictable and dangerous tool in the kit. To be used only when no other option exists (or where no law worth taking seriously exists). If it had to be done, Curtis should have done it himself. But that’s a step he’s not prepared to take yet. And he’s spent years ordering other people to do his dirty work for him. Old habits.

Curtis has a sort of mad ingenuity, when he’s shouldering aside obstacles in his path, but a one-track mind is ill-suited to over-complex plans. It was, after all, an engineer named Kelly Johnson who came up with the KISS principle. (And not Gene Simmons, oddly enough.) You can find many over-focused megalomaniacs in Bond novels and films, making the same mistakes, but what you rarely find there is the carefully crafted inner monologues that bring us to better understand this monster, invite us into his confidence.

And we have to be brought into his confidence. Because Curtis is never, at any time, going to confide the full details of his plans for Hong Kong to anyone, even his closest associates, who think they’re just going to steal a lot of gold, kill a relatively small number of people, and destroy a few city blocks to hide the evidence of their crime. He knows they lack the imagination to encompass something on the scale of what he intends to do. He uses everyone, trusts absolutely no one.

This is a huge break with both the Bond novels and films, and really with most popular fiction involving megalomaniacs and master plans and henchmen. It was a leitmotif in the Bond novels all the way back to Moonraker, with innumerable antecedents, and the movies (lacking as they do a narrator who can put us in the villain’s head) magnified it to the point where anyone writing a Bond flick now has to struggle with a way to justify it.

(I’m curious as to how Westlake would have handled that hoary shibboleth, had his movie been made. It should be said, Bond does at times figure out what the plan is without the aid of egocentric villains, but that often requires him to know far more than he ought to, another problem, that Fleming sort of danced his way around.)

It’s such a well-established trope for the villain to blab his evil plan to the hero that endless parodies have mocked this self-destructive compulsion. that is pretty much entirely an invention of desperate storytellers seeking plot exposition (pretty sure Hitler never phoned Churchill to brag about his V2 rockets). Curtis makes a lot of mistakes, but never that one. Well–hardly ever. Westlake makes a sly curtsey to this tradition in Part One.

Captain Zhang is tormented with guilt and indecision, questioning whether he is the good man he always thought of himself as being–but doesn’t a good man protect his family from privation? He delays as much as he can, hoping Curtis will change his mind, and the delay proves fatal to Curtis’s fatal plans for Kim.

Before Zhang does something that can’t be undone, Manville goes to Curtis and tells him he went to apologize to Kim’s corpse for not putting in the fail-safe (he can be almost annoyingly conscientious at times), and found a warm sleeping body instead. He knows Kim isn’t dead, but he heard Curtis tell an entire dinner party she was.

He’s figured out why Curtis would want her dead, and he figures all he has to do is tell Curtis he knows and the game will be up. Curtis will find some other way around his difficulties. Which is precisely what Curtis should do. But Curtis hates to abandon any plan of action once he’s settled on it.

So instead he shares–just a little. A little too much. He tells Manville he’s really broke. He tells him about what happened in Hong Kong. He tells him about Jerry Diedrich’s vendetta.

“But what does that have to do with that girl, down in cabin seven?”

Curtis thought about his answer, then said, “All right. The fact is, I have a way out of this mess. I am going to be rich again, a lot richer than I ever was before. But I have to be extremely careful, George. What I’m going to do is dangerous, and it’s illegal, and I have to admit it’s going to be destructive.”

“With the soliton,” Manville said.

“I was going to do it without you,” Curtis told him, “and I still can. I’m not asking you to be at risk, not for a second. But you could share in the profit.”

He offers Manville ten million dollars. In gold, if he wants. All Manville has to do is stay quiet. Maybe help out with additional calculations, if needed, though Curtis believes he can do that himself. If he can get Manville to assent to Kim’s death, and by extension to the much larger thing Curtis plans to do with Manville’s idea, he’d be too implicated to speak up later. Would he tell Manville everything if Manville came in with him? We never find out.

It’s motivated quite differently from most Bond stories (though maybe just a bit like the film version of Goldfinger, wanting to bask in Bond’s admiration of his ingenuity). He and Manville have worked together so well, understood each other so perfectly when it came to the project they just completed, that he felt like Manville was, in a sense, his other self, a secret sharer. But this secret was never meant to be shared, not even in a vague hypothetical form.

Curtis can coldly plot the death of millions, order an underling to snuff out a young girl’s life, but hesitates to do the job himself–Manville is the obverse. He can kill if he has to, but he’ll be the one doing it, with whatever tools come to hand. He doesn’t yet know this about himself. We don’t know our limits until they are tested. Curtis has found Manville’s He turns Curtis’s offer down flat. Knowing as he does that now Curtis will try to have him killed as well.

A mistake had been made. Curtis understood that, now; he’d made a second mistake, while trying to adjust for the first. And both mistakes came down to the same error of judgment. He had gauged George Manville too poorly, dismissing him as just an engineer, which was certainly true, but without stopping to think what that meant.

Yes, Manville was just an engineer, and what that meant was, he had too much integrity and too little imagination. Dangle ten million in front of him—in gold, George, in gold!—and he hasn’t the wit to be seduced by it. First he has to take responsibility for the accident to the diver, a responsibility that was never for a second his, but which he assumed for himself simply because he was the project’s engineer. That unbidden, unasked-for scrupulousness leads him to learn the truth about the diver, which makes him a threat to Richard Curtis, to which Curtis responds by making mistake number two. Not taking time to judge his man, he tries to enlist Manville on his side, and tells him too much.

Before this, Curtis had once or twice wondered, if there were unexpected complications down the line, whether or not he’d be able to recruit Manville, and had guessed that a combination of cupidity and the engineering challenge would turn the trick, but now he knew he’d been wrong. Manville was too blunt-minded to be affected by cupidity, and his engineer’s honor would keep him from being caught up by the engineer’s challenge. If he could balk at finishing off one half-dead idiotic girl, how would he react to what was going to happen to all those people in the buildings?

(Parts of this read very much like a film treatment, don’t they? The second paragraph in particular. And we know why, but Westlake usually hid that kind of thing better. He always worried about explaining his characters’ motivations for doing something necessary to advance the plot that didn’t quite make sense in pragmatic terms–as so much human behavior does not, but fictional humans get held to a higher standard, somehow. He thought he’d explained Parker’s motivations too poorly in The Jugger, and sometimes he went to the other extreme, over-explained, to compensate. The simple truth is, people with deadly secrets yearn to share them. Not everything we do makes sense. Understatement of the century?)

Curtis pretends to relent. Manville pretends to believe him. Curtis flies off in his helicopter. Captain Zhang takes a lot more time getting the yacht back to Brisbane than he ought to need. Obviously there’s a plan to get rid of both of Manville and Kim. Manville starts making plans of his own.

In the meantime, Kim wakes up, finds Manville standing guard over her, and is tended to by an increasingly guilt-ridden and confused Captain Zhang. Manville tells her the situation they’re in. But she’s still processing what got her in this situation. Her Quixotic act, what she experienced when the soliton hit, and the price she has paid. The price was knowledge. Immortal no longer.

And once more she remembered her own final thought: Stupid me, now I’ve killed myself. But now she remembered more; she remembered what was inside that thought. Inside the panic and the desperate useless lunge toward the surface, and much more real, had been acceptance.

Resignation, and calm acceptance. She had known, for that second or two seconds, that she was going to die, and she’d accepted the fact, without challenge. She hadn’t even been unhappy.

How easy it is to die, she thought, and realized she’d always assumed it was hard to die, that life pulsed on as determinedly as it could until the end. It was a grim knowledge, that life didn’t mind its own finish, and she felt she had been given that knowledge too soon. I shouldn’t know that yet, she thought, and began to cry. She struggled to keep her breathing regular, to avoid the pain, and tears dribbled from her eyes, and then she opened her mouth and sighed and gave up the struggle and faded from consciousness.

(That didn’t read like a film treatment at all, did it? More like a memory–or a premonition. Westlake put a lot of himself into Kim, as well as perhaps some women he’d admired, and she is, in fact, one of his more successful attempts at a female protagonist. She’ll need to be.)

She’s young and fit, and recovers quickly, but is still too shaky to put on a small boat and escape. Manville has learned from Zhang that people are coming to kill them. That’s why it’s taking so long to get to Brisbane. He hides Kim, but they find her quick enough. He looks for some weapon to fight them with. All he can find is a large heavy pepper mill. He clubs one of the searchers with it, and takes his gun.

He used to do target shooting, for fun. He’s never shot at a living thing. He’s never used this kind of gun before. He has to learn fast.

He stood just out of sight of the people on deck, and studied the thing, a revolver with a bit of bullet showing at the back of each chamber. This small lever here on the side, handy to the right thumb; wouldn’t that be the safety?

The lever moved up and down, and when he first tried the thing it was in the down position. Would the man have done his searching with the safety on or off? There was nothing written on the pistol, no icons, no hint.

I’m an engineer, Manville thought, if I were the one who’d designed this, which way would turn the safety off, which way would turn it on? I would want the more speed when turning it off, would have less reason for speed when switching it on. The quickest simplest motion here is for the thumb to push this lever down, so if I were the engineer on this project I’d design it so the safety was off when the lever was down. The lever’s down.

If I’m wrong, I’ll know it when and if I have to pull the trigger. With luck, I’ll still have time to put my thumb under the lever and push it up. Without luck, I’m dead anyway, because this is nothing I know anything about.

He’s right. And Curtis’s thugs, led by a cynical American smuggler named Morgan Pallifer, who Curtis has had past dealings with when he needed something illegal done, are wrong when they assume he’s bluffing. Well, if they weren’t, that would be the end of the story, wouldn’t it?

So Manville and Kim tie up the survivors, and escape in their boat to nearby Brisbane–Kim has recovered enough by now, and they don’t have any choice. Pallifer tells Manville he’d like to meet him again sometime. Manville, a killer twice over now, much less disturbed by that fact than he would ever have believed possible, responds “I wouldn’t.” End Part One. And I’m well over 6,000 words. Damn.

Okay. One has to adapt to unforeseen exigencies. That’s one of the lessons of this book. I can’t possibly finish all three parts in the next installment. So this will be a four-parter. I’ll try to make the next one brief (it’s my least favorite part of the book). One complication is that I don’t have four cover images for this book. I have two–I’ll save the second for part four–it will be worth the wait. As to the rest, I’ll improvise.

So next time Australia. Then Singapore. Then Hong Kong. If there still is a Hong Kong when this book is finished. And if there still is a world to read this review by the time I’ve finished it. Did you hear that Kim Jong Un claims to have a hydrogen bomb he can fit into an ICBM? Trump has thousands of the blasted things (poor choice of adjectives, that).

Like I said. No shortage of real Bond villains in this world. But if you’re waiting for Bond to show up and save you, well kids, you are just shit out of luck.

(Part of Friday’s Forgotten Books. And I suppose this qualifies, though since almost nobody knew it existed before now…..)