They rode in a taxicab to his rooms. For most of the ride they were silent. Once she said suddenly: “In that dream—I didn’t tell you—the key was glass and shattered in our hands just as we got the door open, because the lock was stiff and we had to force it.”

He looked sidewise at her and asked: “Well?”

She shivered. “We couldn’t lock the snakes in and they came out all over us and I woke up screaming.”

“That was only a dream,” he said. “Forget it.” He smiled without merriment.

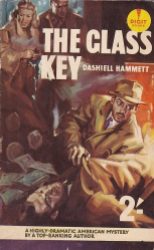

From The Glass Key, by Dashiell Hammett

The Glass Key was an unqualified success for Hammett, a big seller, inspiring two film adaptations, neither of which captured the book’s spirit, but both of which made money. It proved he could write from the perspective of criminals, instead of detectives, even if those criminals were, you might say, something of an aristocracy–existing in the space between the law-abiding and the lawless.

Critics have disagreed ever since about its place in the canon, some concurring with Hammett when he said it was his best book (never trust authors on the subject of their own work). Others, like me, thought it was his worst. (You don’t have to trust me either.) It has somewhat languished in the shadow of the Continental Op stories, The Maltese Falcon, and The Thin Man, which would tend to bear out its detractors, at least so far as enduring popularity is concerned. But it could hardly be called a forgotten book. (The two I’m reviewing here qualify.)

Graham Greene and Raymond Chandler both liked it. Greene liked characters with opaque motivations in stories with a harsh moralistic edge. Chandler liked confusing plots that ended with the ambiguous hero going off with the girl (ambiguously). So really, they were complimenting themselves.

Hammett’s #1 critical fan at the time was probably Dorothy Parker, who wrote in The New Yorker that she adored The Glass Key, but not nearly so much as The Maltese Falcon, which had appeared a short time before. Writing more of a mash note to Hammett than a serious review (you’d have to look long and hard for anybody writing serious reviews of Hammett back then), she doesn’t go into much detail about why she prefers the previous story, but I can hazard a guess. The people.

Ned Beaumont is a hazy sort of hero, who blunders around in the dark, his motives undefined, his agenda scattered, shifting. Sure, you could call that post-modernism before anybody called it that. Since I hate post-modernism, I call it a writer who hasn’t quite figured out who his protagonist is, or what he’s trying to get across with him, and is hoping if he writes enough, he’ll figure that out. Since Ned Beaumont isn’t a series character–is all used up by the end of his one and only story–that wasn’t a viable approach.

The Maltese Falcon has a much better-defined hero (self-defined, in fact), who still has plenty of inner mysteries we can speculate about–he’s also, to some extent, a romanticized more independent version of The Op, so Hammett had a grip on him going in. He wasn’t starting from scratch.

Spade has a trio of eclectically eccentric villains to best, while Beaumont has to make do with a big dumb lug of a henchman, and a stage Irishman of a gangster whose comeuppance is a mite too contrived. Spade also has not one but three interesting women vying for his attentions, each in her own signature style. Say their names with me–Brigid O’Shaughnessy, Iva Archer, and the ineffable Effie Perine, mother of all Gumshoe Gal Fridays–and still the best of the bunch.

Now try to name the The Glass Key girls. Drawing a blank? I typed the name of the main girl repeatedly in the last review, and it’s gone out of my head. She gives the book its title, serves as its primary plot complication, and I like the book much better when she’s not around. Her name’s Janet. I looked it up just now. I’ll forget it again in no time. Even though she’s helping Ned solve the mystery (or thinks she is), she seems not so much co-detective as co-dependent, not so much love interest as sex irritant.

Hammett crafted far more diverting damsels in all his other novels, and many of his short stories. Most of all, he dropped the ball with the females in this book. And who’d mark that deficiency more acutely than the Queen of the Vicious Circle? If Mrs. Parker loved Hammett to the point of mania, it was not least because at his best (and his worst) he really does get women, in all their perplexity of purpose. Never met a pedestal he didn’t want to kick over. He was far from perfect himself, and he never expected perfection from the fair sex (who ain’t so fair when it comes to that).

By the ordinary standards of hardboiled detective fiction, the women in The Glass Key are fine–typical, even. He’d set a higher standard. (In his next and final published novel, he arguably surpassed it.)

But in labeling this book a disappointment, its hero an unsatisfying cipher, I can’t call either a complete failure. As I said last time, Hammett had come up with one hell of an interesting set-up for a mystery, and a useful protagonist prototype. Problematic, to be sure. Perhaps unperfectable.

But in the decades following its publication, The Glass Key would prove a perennial temptation to other writers in the genre, each seeking the ideal combination of elements that eluded the original story’s creator. Those seeking to emulate and improve upon Hammett’s magic would craft their own duplicate keys–only to have them shatter inside the lock. Every time? Let’s see.

I can’t possibly find all the duplicates (could be dozens, for all I know), but the earliest I’ve come across was written by James M. Cain, and published in 1942. Let’s take a sideways look at—

Love’s Lovely Counterfeit:

She got the solemn frown on her face again, as though she wanted to make clear that it was no ordinary greed that prompted her present activities, but he ran his finger up the crease between her brows.

She laughed. “I want to be an idealist.”

“O.K., so I’m a chiseler.”

“Oh, say crook.”

“A chiseler, he’s not a crook.”

“He certainly isn’t honest.”

“He’s just in between.”

Two days before, when Lefty had said it, Ben had obviously been annoyed. Now, just as obviously, he was beginning to be proud of it. She laughed. “Anyway, we’re both walloping Caspar.”

Today, James M. Cain is remembered for The Postman Always Rings Twice and Double Indemnity–and (it’s an old refrain) much more for the films inspired by his books than for the books themselves. And there are reasons for that.

Joan Crawford buffs may recall that he also wrote Mildred Pierce–he dabbled a lot in melodrama, and never went in much for detectives. There’s quite a lot of melodrama in this book, but it’s a crime novel, with a mystery to solve, and I liked it–and found myself losing interest too often. His style hasn’t dated well.

Honestly, I wouldn’t have twigged to it being a duplicate key (or should I say counterfeit?) if I hadn’t seen the movie made from it, with a more memorable title. Maybe the only early color noir worth talking about, and I’ve watched it multiple times, because I’m a sucker for redheads.

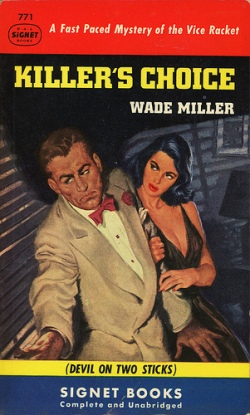

(Some posters didn’t bother with Payne at all.)

Cain’s book likewise has two sexy sisters setting their sights on the Ned Beaumont clone, but neither has Titian locks. And this version of Beaumont is not big on loyalty, at least where bosses are concerned. But the novel is a very different thing from the film, the latter of which I slightly prefer. I can’t say how much of that is based on Arlene Dahl in a leopard-print one-piece. Nothing against Rhonda Fleming, but Dahl steals the picture, which kind of tracks with her character.

Cain’s story has the same bones, connected differently. Ben Grace, errand boy for Solly Caspar, head of the local syndicate in a sewn-up midwestern town, has no love whatsoever for his employer, who treats the good-looking college grad come down in the world with amused disdain. A major variation from Hammett’s bromance between Beaumont and Madvig and intentionally so–what if the fixer decided to fix things up for himself?

When deployed by Caspar to keep a troublesome political reformer at bay, Ben figures out he can use the do-gooder–and the do-gooder’s half-good assistant, a black-haired beauty named June Lyons–to give his boss the push.

By half-good, I mean June wants to do good, but she also wants to do well–and she’s got this younger sister she has to support, who shows up much later in the story than the equivalent character in the movie, who is there from the opening credits. (Because Dahl lived up to her name, and you wouldn’t want to wait that long to see her.)

Aside from her financial needs, Ben’s a smart tough ex-football player who stayed in shape, and let’s just say Hollywood doesn’t always screw up the casting for crime novel adaptations (just when it really counts). Ben Grace is a man who gets what he wants, and right now he wants June–just not the same way she wants him.

They go sleuthing and swimming together on a lake, find a dead body, and get a good look at each others’ bodies in the process. With her help he finds evidence that leads to the boss leaving town in a hurry. Which he figures makes him the boss. He takes over the organization without firing a shot. All this adventure turns June on no end, but Ben’s all business.

He’s got the reformer, now mayor, to make things look legit. He’s got June, the girl the reformer is enamored of, to run interference with the mayor (who is uncomfortably aware that Ben helped get him elected).

He’s got a powerful ally on the police force (who isn’t 100% reliable). He’s going to work the same old rackets, like pinball gambling machines, but dressed up to look like it’s just fun for the kids and a little extra cash for local merchants. He literally just refits the original machines, discarded when the old boss went on the lam–pulls them off the scrap heap, sticks new decals on them. The same old machine underneath. Nice metaphor. You get a lot more details about the seamy side of politics than you do from Hammett in The Glass Key.

Nobody gets hurt, and Ben gets rich. He also gets June, a fringe benefit he enjoys (not in public, because the mayor still wants her). He’s not gone for her, as she is for him. He’s never experienced that sweet insanity. Can’t fathom it. You see where Cain’s going with this? It’s the punch you don’t see coming that knocks you out.

See, this heel is of the Achilles variety. A recurring weakness of Cain protagonists, keeps tripping them up. He’s got the last lingering ghost of a conscience, can’t commit fully to thug life. If June’s not as good as she wants to be, Ben’s not as bad. And the very last thing any heel ever needs is to fall head over heels himself.

But he does–for Dorothy, the younger of the two Lyons girls, who June has been fighting for years to keep out of prison. A luscious light-haired klepto, with no conscience at all–and to Ben’s astonishment, and June’s horror, his soulmate. They take one look at each other, and June might as well be on the moon. If you really need a woman to back you, for your organization to stay afloat, probably shouldn’t fuck her kid sister.

Solly comes back for revenge, Ben kills him, and Dorothy’s the witness. He tries to hide the body, but June rats them both out, hell hathing no fury and all. They go on the run, finding a big stash of cash from the old operation–and solving a murder into the bargain, not that either of them cares, and frankly, neither do we.

The love of a bad woman, combined with the looming threat of the electric chair, has made Ben want to reform, join the war effort in Canada (which won’t ask too many questions), start a new life with Dorothy, who is gone enough on Ben to try and quell her larcenous habits for now.

But the bum luck of Cain’s anti-heroes is legendary. They both get nabbed by the law, Ben badly wounded, Dorothy having no choice but to testify against him for Solly’s murder (which was self-defense, but with everything else they have on him, the judge won’t buy it).

He has one last trick to play, a variation on that old scene where the detective brings everybody together at the scene of the crime, but he’s the criminal, and detection is not his game. It’s romantic as all hell, but if I explained how, that’d be a spoiler. I’ll say this much–Jim Thompson read this book. And I suppose you could argue that The Killer Inside Me is a duplicate duplicate key–and a really twisted one–but I’m not going there (Yet.)

This has never been considered one of Cain’s best books (nor are most of his other books), and it’s the only one I’ve read, so I shouldn’t form any snap judgments. I can’t help but note a lot of problems with his prose, which is a bit overstuffed–about par with most best-selling books of that era that nobody reads now. He doesn’t cut to the chase enough, even though it’s by no means a long novel. It doesn’t have Hammett’s efficiency, or his intelligence. It does spend a lot more time dealing with the practical implications of practicing corruption without calling it that.

Ben Grace does not have a way with the witticisms like Ned Beaumont, his motives aren’t particularly mysterious. The most interesting relationship in the book, his partnership with June, could have been fleshed out a bit more (you know what I meant–okay, I meant that too). The most important relationship in the book, his ruinous romance with Dorothy, gets short shrift because Cain saves it for the end, and they barely have time to talk what with all the surreptitious screwing.

That’s his point, though–the man who thought he figured on everything never figured on falling for his girlfriend’s sister. Nobody’s as smart as he thinks. But love–or its counterfeit–does get one last inspired maneuver out of Ben. I think Cain’s one of those crime writers (like W.R. Burnett) more significant for who he influenced than what he wrote himself, but one of these days, I am going to read Double Indemnity (a novella), and see how it matches up to the Wilder/Chandler version.

Cain wrote this maybe a decade after The Glass Key came out, and he went to some pains to change the story around. This is the most divergent of the duplicates, where the relationship between fixer and boss is antagonistic from the start (and the fixer becomes the boss early on). As a general rule, the fixer survives in these stories, but rules are made to be broken, just like glass keys.

Women matter a lot more than in Hammett’s book, and not just sexually, though definitely that–you can see Cain’s stamp on what would soon be a roaring trade in spicy paperback originals, featuring dissolute amoral protagonists, satisfying their animal lusts, to the general delight of the strait-laced law-abiding populace.

I’d have said the book was well worth reading just for the scene where June strips to her skivvies and dives into the freezing water of the lake, as the two search for a body hidden there–telling a shivering Ben that women can handle the cold better than men. And he’s impressed, but still–not stirred on any deeper level. (More fool he, I’d say, but again, that’s the point.)

For all its fleshy pleasures, it’s the weakest of the duplicate keys. Like Ben Grace, it’s not committed to the criminal path it’s chosen–written a bit too much to the mass market. And yet, looking up the review in the Times, I saw that it got more ink there than any Westlake tome I can think of–though the review is condescending and dismissive, it’s still a review of a mainstream best-selling author. “Here’s a nice piece of trash, if you’ve got the time and inclination to read it.” Many did. Few remember it now.

Cain’s novel began life as a hardcover, and so did the next key in our chain, written by a guy named Wade Miller, who was actually two guys from San Diego, pals since the age of twelve. That friendship spawned a fruitful collaboration in what might be called the middle period of 20th century crime writing–after Hammett and Cain, before Westlake and Block.

Unlike Cain, detective stories were their primary stock in trade, but like Hammett, they saw the value in branching out, looking at things from the criminal’s POV. They also saw the potential in a gangster’s right-hand man being forced to solve a mystery–but they had their own idea about how that would go, and how the experience might impact said crook, in a 1949 effort with the rather odd title–

Devil On Two Sticks:

Thursday, May 19th, 4:00 p.m.

THERE WAS ONE PARKING PLACE OPEN NEAR THE Cathay Gardens when Steven Beck came along in his Buick. A gray sedan had pulled up ahead, ready to back into the opening. Beck tapped his horn and slid his Buick coupe in instead. The driver of the gray car glared back, mouth working. Beck met his eyes and laughed. The other driver shifted gears savagely, spurted away through National City.

Beck got out of his black coupe on the curb side and walked back three buildings to Hop Kung’s Cathay Gardens. His body moved as always with a quiet surety, as if convinced its every move was valuable. His was a solid medium-sized body, conditioned in a club gym, tanned by sunlamp. An afternoon breeze ruffed his hair pleasantly, taking the curse off the high May sun, the California sun he seldom had time for.

He looked younger than he was. Part of this discrepancy was his crisp brown hair, cropped short like a college man’s, and part was his clothing. Beck wore a tweed suit, slipover sweater and bow tie. His eyes, light brown and thoughtful, were his softest features. Nothing immature showed in his blunt face. Patches of steel-gray bristles at his temples were clipped near to invisibility. He carried his mouth locked shut but in the beginnings of a smile.

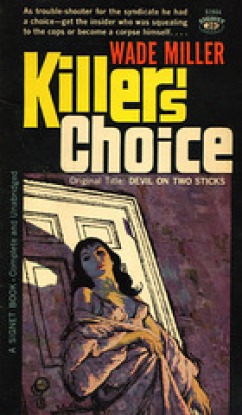

I first encountered the sleuthings of Robert Wade and Bill Miller via some dusty old paperbacks that came my way via my sometime partner in crime, Ray Garaty, who used to have me buy up big ebay lots for him, and I could have the books he didn’t want (as rackets go, I’ve seen worse). Two of them were paperback reprints of Devil on Two Sticks, under the same alternate title. (The original is derived from an 18th century French satire.)

(I have both Signet editions, but read the one on the left, because damn that’s nice art.)

I got a few Max Thursday novels into the bargain, perused them, but those editions were not in great shape for reading–all six, published between ’47 and ’51, are now available for Kindle, and if you follow that link to Thrilling Detective, you can snap them all up for $3.99 a pop, like I just did.

A San Diego based P.I. ahead of his time, was Max. More vulnerable and emotionally complex than maybe any other fictive gumshoe of that period (or most of those that followed). Good at his job, but at the same time a bit of a loser–particularly when it came to love. A recurrent theme with Messrs Wade & Miller. One can also find it in Hammett, on a minor key. And in a different way, in Westlake, particularly when he’s writing as Tucker Coe.

(One thing this novel shares with the Thursday books is each chapter beginning with a date/time stamp. Very X-Files. 40+ years before The X-Files. This book we’re looking at came out roughly in the middle of the Thursday Era, so there’s some overlap. No ebook, sadly. Most of their work is out of print.)

Steven Beck is a fixer for a southern California syndicate called ‘the circle,’ operating out of National City. (All the duplicate keys save this and one other are set in towns that don’t exist, just like the master key.)

Like Ned Beaumont, he’s only been with this outfit about a year, and has quickly become indispensable, respected by his colleagues, and somewhat feared. He’s got a mind like a computer; precise and capacious, packed with information on anyone who might be useful to his boss.

“State Senator Gene L. Wake. Some papers call him The Parimutuel Senator. Talks like a farmer, dresses like a farmer, but grew up on Main Street, L.A. Gambling lobby in Sacramento. One of the Fierro’s front men before Fierro retired. In state politics for about, oh, seven, eight years.” Beck tossed off his drink, went to pour another.

Behind him, Garland laughed. “What’d I tell you, Gene? Like clockwork.”

Wake’s twangy voice complained, “Downright uncanny, considering I don’t have a name this far south. How’s he do it?”

“I don’t know. How do you do it, Steve?”

“Professional secret.”

“You left out only one thing,” said Garland. “Gene may be our next governor.”

Beck sat down again, held up his glass. “God save California.”

His boss is Pat Garland, a big man, getting bigger, who runs a good-sized territory, has at least one major state politician on the payroll (see above) who shows up with unsettling news–somebody inside the organization is feeding intel to the state Attorney General’s office. A plant. A cop of some kind, posing as one of them, who Steve can tell from the letter Wake got via a bureaucratic snafu must have legal training.

No way to fix the AG’s office, so they’ve got to fix the leak, which means fixing the leaker. Has to be someone who joined up not much more than a year ago, fairly high on the food chain, which narrows it to six suspects. One of whom is Beck, but he’s prominently mentioned in the letter, and Pat trusts him–mainly. He gets the enviable task of checking out the other five. He’s a detail guy, so he’s got a question.

“One more point. When I dig up this AG man–what do I do?”

Garland paused, replacing the bottle. His face was surprised. “Do you have to ask? You kill him.”

“I just like to be accurate,” Beck said.

Now when I reviewed The Glass Key, skimping on the synopsis more than I normally do, I neglected to mention one vital plot point–Ned Beaumont learns that somebody is sending poison pen letters to newspaper editors and law enforcement personnel, implying Ned’s boss and buddy, Paul Madvig, is a murderer, and is using his political clout to cover it up. That was kind of a big thing to skip over. (I like to be accurate too, but sometimes space considerations get in the way, and this is looking like a five part series anyway, so bear with me.)

A big part of the story hinges on who’s writing those letters, and how Ned figures that out. However, since Paul is strangely indifferent to the whole matter, Ned is doing this strictly on his own time, for his own reasons, chief among which is his friendship with Paul.

Cain didn’t really touch on this in his duplicate key, though there’s a hint of it in June’s jealous betrayal of Ben and Dorothy–no anonymous letters from an informant within the mob, and Ben’s too busy hatching schemes and juggling sisters for most of the book to do much detective work. Cain wasn’t much interested in that kind of mystery. Hammett was, but wanted to prove he could write something else.

Wade & Miller, full-time gumshoers that they were, saw unrealized potential there–what if the fixer was professionally obligated not only to play shamus but judge and executioner into the bargain?

And what if he was neither bosom buddies with the boss, nor looking to do him in, take his place? Loyalty is not a big thing for either of them. He and Pat are friendly, but not friends. Beck takes pride in doing his work well, for its own sake, and for the handsome financial compensation that comes with it. It’s what he does, therefore who he is, and he’s learned to keep his feelings buttoned up, since they get in the way of doing the job. He’s not emotionally involved with anyone or anything. Like Ben Grace, however, it’s going to be emotion, relating to a woman, that does him in. (I’d say Ben gets off easy by comparison, but it’s debatable.)

As he goes from suspect to suspect–while Pat wonders if maybe Beck’s the plant, no Madvig he–Beck encounters Marcy Everett, self-styled black sheep daughter of the organization’s shady lawyer, J.J. Everett, who is another suspect on the list (he’s got the legal training). Much younger than him, tawny hair, slim build, modern morals (they had those in the late 40’s too–I doubt there was ever a time they didn’t have them).

Just like Ben with Dorothy, he’s taken aback at how quickly he falls for her–starts out as mere lust, quickly morphs into a strong protective urge. Only (variation time again) she doesn’t fall for him. They have a fast flirtation, an enticing first date, she’s definitely into him–but her roving eye turns to yet another suspect on his list, a younger man, Eddie Cortes, tall and swarthily handsome, reputed to have been a rather brutal pimp down near Mexico, before joining the circle. Good dancer.

By the time Beck realizes what’s happening, it’s already happened. It creeps up on him slowly, sharp operator that he is–it’s maybe the one thing we the readers pick up on before him. Nobody’s smart about love.

Unlike Cain, who didn’t want to hew too close to Hammett’s book (already a movie by then, another one coming, so that was prudent of him), Wade and Miller cover every major plot point from The Glass Key, and you can tell how much fun they had taking it apart and putting it back together, knowing that only fellow mystery mavens will spot the references. (The English Bulldog becomes a Persian Cat, if you’d believe it.)

The early near break-up between Beaumont and Madvig? Garland nearly has Beck whacked, thinking he’s the spy, a notion encouraged by J.J. Everett, out to save his own neck. When that’s cleared up, Beck almost quits in a cold rage–but Garland sweet talks him back in, offering a raise. There’s no love between these two at all, but they work well together, and Beck is all about the job.

Well, maybe not 100% about the job. Beaumont walking away at the end with the girl of Madvig’s social-climbing dreams? The equivalent in this book is Leda, Garland’s tall classy black-haired swan of a wife (that’s her on the left-hand paperback cover), having a risky extramarital fling with Beck that he’s about ready to end, thinking he’s still got the inside track with Marcy–but Leda’s not ready to let him go.

The dialogue in this book is first-rate. According to this piece, the way the partners worked was to outline carefully, then they’d take turns writing drafts, each revising the other, until they had it just the way they wanted. A very precise well-calibrated book would result, with each man contributing something of his own, but you’d be hard pressed to see the joins. Never seems written by committee. You get some nifty philosophizing along the way here, and it ties in neatly to the theme of the book, and its machine-like protagonist.

Here’s a good sample from late in the story–a cocktail party at Garland’s house. Leda’s just tried to seduce Beck. J.J. Everett (Marcy’s father, remember, who has just asked Beck to stop Cortes from dating her, not knowing Beck already has). The Tarrants are there, members of the circle, who just lost a key employee because Beck incorrectly fingered him as the spy, and Garland wouldn’t wait for confirmation, but subsequent events have proven they killed the wrong man. Garland’s angry about that, and that an underling of his has not shown up for the party.

J.J. is now Beck’s #1 suspect. But it’s a cocktail party, and they’re going to pretend all that isn’t happening, and J.J. will talk to distract Garland from his rage. Sophisticated upscale gangsters. Not a goombah in the bunch.

(If it helps, I’ve headcast J.J. as William Powell.)

Everett repeated, “I’ll tell you how and why. Homo sapiens, the wise animal, has evolved from the more bestial, more complete animals. We are weakening because of the mixture we’ve made of ourselves lately. I’d say we had abandoned humanity almost entirely in order to breed the machine and we can’t survive, half-animal and half-mechanical. You see, the next evolutionary step is the pure complete machine. So let’s reconcile ourselves to making way.”

Leda, rustling by Beck, murmured, “What’s he talking about?”

Beck shrugged and said, “Somebody has to.”

She glanced towards her husband’s morose bulk and bore out some more dishes.

Everett said, “We were goners, you know, as soon as we accepted machine ideals as our ideals. And don’t think we haven’t. We even believe that human nature is inferior to the machine, which is perfection. We admire its accuracy, its speed and strength, its impersonality, and its standardization, which is the machine word for our own beloved conformity. Especially we envy the absolute neatness and comfort of predestination. That’s the basis of all machinery.”

Beck gazed stolidly back at him. He felt irritably that the lawyer was making fun of him in some obscure fashion Now that an explosion from Garland had been averted, he wished that Everett would shut up.

He doesn’t, of course (William Powell, remember?). He expands on his theme at some length, even brings up cybernetics, “the machinery to replace brains,” and if you’re not impressed by that, please recall this book is copyrighted 1949 and its authors didn’t write science fiction.

Beck’s not sure if J.J.’s poking fun at him personally, or the whole world, and either way it bothers him. Because J.J.’s right, and he’s the future? Or because J.J.’s wrong, and he’s just another failed experiment, still all messy and emotional on the inside, for all his attempts to suppress it, tick smoothly like the expensive chronometer on his wrist? He takes Marcy on a late date that very evening, the dog track, where they watch greyhounds chase a mechanical lure they never will catch up to.

He brings up Cortes–and what Cortes does for a living–knowing Marcy is aware of ‘the circle’ her father is part of, wary of Beck because he’s part of it too. That goes about as well as you’d expect, and then Leda shows up, which goes even better. Any chance he had left with Marcy (not as modern as she thought) doesn’t survive the encounter. He finds her later at Eddie’s place, and it’s a bit too soap opera, but so are people a lot of the time, when their hormones get going.

So after the sad predictable scene has played itself out, he’s ready to finger J.J. just to get even with her. His rage has to expend itself somewhere, but it has to be a sanctioned target. He still has to do his job right. His job is all he has left. Or rather, his job is all that’s left of him.

The Shad O’Rory of the piece–a subordinate looking to take out Garland and become the new boss–comes along very late in the story here (with the Persian Cat), and wants Beck to come in with him–or else. Beck may not be loyal to Garland, but he’s loyal to himself–his sense of professionalism. Instead of ending up in the hospital, like Beaumont, Beck puts the turncoats in the morgue. (Don’t worry, the cat is fine.)

(This, incidentally, is where you maybe should stop reading if you don’t want to know how the story comes out and who the informant is.)

He gets a call from Leda, as he patches himself up. She’s not accepting their affair is over. She’s ready to blow their whole world up to keep him, if that’s what it takes. He will have her or a bullet from her husband. Is the general gist. Just to make his day perfect.

He decides to go get drunk. He has to figure this out. Isn’t he the machine man, the splendid automaton, the guy who always wins? This never happened to Ned Beaumont! Even Ben Grace had not one but two girls–sisters at that!–madly in love with him before meeting a dramatic end of his own choosing. Who’s the anti-hero of this story, anyway?

Then just what was he: Steven Beck? The bursting light of answer he could believe burned around him and through him. He was clockwork. He was caught in the wheels so he was caught in himself.

No, he couldn’t see any difference between himself and a machine. He had all the same virtues. He liked to be accurate. Why? He stuck the question into himself viciously. What was so wonderful about facts when they had gotten him into this position? After all, two plus two only equaled four because the whole world had agreed that they should. What was so wonderfully worshipful about that?

And what really irks him, more than anything else, is that Marcy can’t see Eddie Cortes for what he is–she’s spent time with him, she must have seen his sleazy moves by now. He knows Marcy was drunk the night Eddie took her home, he would have taken advantage, that cheap whore-mongering–wait a minute.

What if he’s none of those things? What if Marcy is seeing the real Eddie Cortes–the one nobody in the circle ever sees? What is there is no Eddie Cortes? Or used to be and is no more, leaving his identity available to be borrowed? One might say illicitly, but…..

Beck goes to brace Eddie at a nearby beach resort–Marcy’s there with him, in the water, wearing a white swimsuit–not wanting to talk to Beck, she keeps her distance. Which is fine by him. He hasn’t come to talk to her. He shows Eddie the palm gun he got from one of his would-be killers–he normally never carries one–and tells him the game is up.

‘Eddie’ puts up a token resistance, then spills, figuring he’s dead either way. His real name is William Joseph Allison. Never got so much as a parking ticket in his life. He did legal research in the AG’s office, wanted to try undercover work. This was his shot. Maybe a bad choice of words.

His Latin looks, that qualified him to take the real Eddie’s place, he came by honestly, through a Mexican grandmother. (Well, I guess we all come by our genes honestly, if nothing else.) Eddie Cortes drank himself to death right after he got out of San Quentin, and that was an opportunity they couldn’t pass up to take out Garland’s circle.

He tells Beck it’s all over, either way–they’ve got most of what they need–they could use Garland’s ledgers, that he’s been hiding from them, all those names and figures–if Beck were to provide them, he’d maybe get a light sentence…..

No dice. That would be unprofessional. He’s already sent Garland claim tickets for the books via the mail. There’s a looming gang war, due to Garland’s own stupidity, his inability to control his emotions. Beck knows, however, that he could fix it all. He could fix the machine, end the war, outwit the law. And kill this bastard who stole his girl right out from under his nose. Of course he’d have to kill her too.

And this is where Steven Beck decides he’s not a machine. He does have a choice. Marcy loves this bum, and much as he hates to admit it, the bum is worthy of her. More than he is, anyway. She hates him now, thanks to Leda. Killing his rival won’t get him what he wants. Even if he fixed Pat’s wagon, Leda would end up fixing his. He’s got plenty saved up. He just has to leave the state and lay low. Pat won’t last much longer without him. Beck won’t be a cog in a machine anymore–not Pat’s circle, and not Eddie’s either.

He asks a stunned Eddie/William/Whoever to tell Marcy the truth sometime–wishes him luck breaking the news that he’s been lying to her, is going to put her daddy in jail. They might catch Beck too, someday–but he doesn’t think so.

Wearing the same enigmatic half-smile he had when the book opened, he walks away on rubbery legs, wobbling a bit in the sand. He’s lost the whole world and gained his immortal soul. (Who does that remind me of?)

In just about every way I can put a finger on, this is a better book than The Glass Key. Better plotted, better motivated, better denouement. More honest. Starker, you might even say.

It also does a better job than either Hammett’s or Cain’s book with regards to discussing the relationship between organized crime and government–the little corruptions that don’t seem to matter much, taken one at a time. After all, Garland reasons earlier, they’re just providing entertainments people want, like gambling. Maybe they’ll get into drugs sometime (Beck’s against it), but that’s just another entertainment. Wade and Miller get into the weeds of what a fixer does, the arrangements such a person has to make, the people he has to meet in a working day, maybe smoke a cigar with, hammer out deals with. Like these fine citizens.

(I had not realized, when conceiving this series about fictional fixers some weeks back, how au courant it was going to become, but that’s happened to me before.)

It’s better than Hammett’s book in every way but one, but it’s a big one–style. Excellent writing, but a bit mechanical itself, at times. Maybe a bit too geared to the style of 50’s paperbacks, delicious as that can be. It’s very good writing, exceptionally good–not great. Because the style isn’t quite there.

Two close friends writing as one collective entity (under a number of pseudonyms besides Wade Miller) can have the same interests, the same preoccupations, the same overriding themes, the same piercing intelligence–but style is a fingerprint. When it’s two fingers, from two different hands, the print gets smudged a bit. Unavoidable.

I wouldn’t say they don’t have any style–more than I’d have thought possible–but how many ever had it like Hammett? It’s a quibble; a damned subjective one, and you don’t have to agree with me. I don’t even agree with myself. I think it’s a damn shame most of their books are out of print. Bill Miller died in ’61, same year I was born (same year Dashiell Hammett died)–only 41 years of age. But Bob Wade carried on after him–never again as Wade Miller, though. A 29 year partnership. How many marriages last that long? And produce so many gifted offspring?

I’ve got four more books (and one film) to review, and my point in all this is not to say that these writers all read The Glass Key and went about retooling it to their own specifications. It runs deeper than that. I’ve little doubt Wade and Miller read Cain’s book as well. (Beck, like Ben, gets caught between a dark-haired woman with connections, right around his age who he doesn’t love, who won’t let him go–and a younger, flightier, light-haired woman he loves too much, and he has to let her go. It’s easy to see when you’re looking.)

And we’ll see that progression, that accretion of influences, as we make our way through the remaining duplicates. I’ve no doubt at all that Westlake read Devil On Two Sticks. It’s too skillful for anybody in that genre who cared about good writing to ignore. There are numerous little moments in the book that remind you of Westlake–not least the fascination with identity crises, and professionalism. He was studying Wade and Miller. Thinking of ways he could improve on their improvements. Carry the torch a ways further.

And we know for a fact Westlake read everything ever produced by the next keysmith in our chain. Fellow named Peter Rabe. Who you might say made stories about mob fixers something of a specialty. Nobody ever did more of them, and nobody ever did them better. He even gives us three possible endings for the beleaguered fixer:

(1) Dark yet hopeful.

(2) Tragic yet thoughtful.

(3) Jarring yet joyful.

(My vote for Michael Cohen is “sordid but lawful.” Isn’t that awful?)

(Part of Friday’s Forgotten Books–haven’t typed that for a while.)