It stood in a corner, near the bookcase, on a low pedestal nearly hidden from view. White, small, alone, bent by grief, the mourner stood, his face turned away. A young monk, soft-faced, his cowl back to reveal his clipped hair, his hands slender and long-fingered, the toes of his right foot peeking out from under his rough white robe. His eyes stared at the floor, large, full of sorrow. His left arm was bent, the hand up alongside his cheek, palm outward and shielding his face. His right hand, the fingers straight, almost taut, cupped his left elbow, the forearm across his midsection. The broad sleeve had slipped down his left forearm, showing a thin and delicate wrist. His whole body was twisted to the left, and bent slightly forward, as though grief had instantaneously aged him. It was as if he grieved for every mournful thing that had ever happened in the world, from one end of time to another.

“I see,” said Menlo softly, gazing at the mourner. He reached out gently and picked the statue up, turning it in his hands carefully. “Yes, I see. I understand your Mr. Harrow’s craving. Yes, I do understand.”

“Now the dough,” said Parker. To him, the statue was merely sixteen inches of alabaster, for the delivery of which he had already been paid in full.

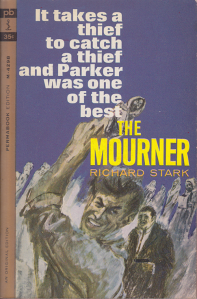

We might as well ask ourselves at this point–who the hell is Richard Stark? Originally, just a name Westlake had submitted a few short stories under, none of which were terribly different from what he wrote under his own name. Then a name Westlake chose to use for a one-shot novel about an amoral armed robber, that turned into 24 novels written over a span of about 45 years, because an editor at Pocket Books really enjoyed the first one, and wanted to read more about this guy.

Westlake could only do one novel a year under his own name for Random House, and he was good for a lot more books a year than that. He needed an outlet for his burgeoning creative energies, and he needed to make more money for his burgeoning family (ex-wives and all). If he wasn’t writing crime books as Richard Stark, he’d still be writing sex books as Alan Marsh. So above all else, there’s a pragmatic side to it.

But right from the start, and more with each subsequent book, Stark wrote differently than Westlake. He used fewer words, for one thing, but that wasn’t because he didn’t know all the same words Westlake did–laconic by choice, not necessity. Less likely to go off on tangents–more focused, more intense, but also calmer, somehow. More deliberative. More objective. More methodical. Less judgmental. He tells you the story, and lets you figure out how you feel about it. He may have a point of view, but you’ll never be quite sure what it is. As opposed to Westlake, who is perfectly okay with you having your own take on his story, but is still going to give you his own, because that’s part of the fun of being a writer, right?

Westlake, writing pretty much entirely in the first person at this point (at least in his novels), has his narrators go on at some length about their their experiences, their outlooks, their worldview. They don’t just narrate, they philosophize. We know who they are, because they tell us, in great detail, how they got where they are, why they are the people they came to be, and we see how their experiences change them, for better and for worse. And we see things entirely from their perspective, of course–we see every other character through their eyes.

But Stark, writing in the third person, with a protagonist who isn’t remotely interested in sharing with the reader, sees no reason to try and justify his actions, whose origins will always remain obscure (and downright unaccountable), who seems to have no opinions that don’t directly relate to the job at hand, no interests other than getting paid and (eventually) laid–you see the problem. Stark has no choice but to jump over into the heads of other characters in the book, some of whom basically become protagonists in their own right, short-lived as they often are.

Parker is only interesting when he’s active, engaged, and he seems to require long stretches of complete inactivity and total disengagement. How many pages can you write about Parker sitting in a dark room, with the TV on, staring blankly at the screen, not taking any of it in? That’s good for one short enigmatic paragraph. At best.

Ipso facto, there is not one Parker novel written entirely from Parker’s perspective. And that’s for two reasons–the first being that Parker’s consciousness, his interior castle (to borrow a phrase from St. Teresa), is too sparsely decorated, too perfect in its simplicity–and the second is that we want to see Parker through the eyes of other people, to get a different perspective on him. People whose interior castles are anything but simple. People who do have worldviews to share with us. People we can actually understand, if not necessarily approve of. People who stand in contrast to Parker himself. The books are an exercise in comparative psychology. Among other things.

So anyway, this book directly follows up on the events of The Outfit. Parker and Handy McKay are out to steal a small statue from a foreign diplomat for Bett Harrow’s industrialist father, who paid them $50,000 in advance to do it–Parker doesn’t like the set-up but he agrees to it because Bett has a murder weapon with his fingerprints on it to trade–technically it was self-defense, but Parker knows he’s never getting off on any technicalities. He could just disappear and create a new identity, but that’s a pain to do, so he figures 25k is a decent enough haul. He never bothers to tell them he’s got a partner to split with, because they don’t need to know that.

Mr. Harrow thinks Parker needs to know the full history and provenance of this statue, which is one of the lost Mourners of Dijon (yes, they really exist, that’s a picture of some of them up above, on tour at the Met), and he simply can’t understand why Parker isn’t even a little bit interested–doesn’t this man understand the concept of plot exposition?

Parker doesn’t give a rat’s ass about plot exposition. Parker just needs to know where it is, what it looks like, and a blueprint of the house would be good. Art has absolutely no meaning to Parker. It does not exist for him. The Lost Mourner of Dijon might as well be a garden gnome from Walmart, as far as he’s concerned. He’s not a philistine, because a philistine has bad taste. Parker has no tastes of any kind when it comes to anything other than women–he’s not all that picky there in a pinch. Art is only meaningful to him as a potential source of income. But he’d so much rather steal cash. Simpler.

And yet, because he spent a few nights in the rack with a rich leggy hollow-cheeked blonde with a taste for violence and manipulation, he’s forced to become an art thief. And to listen to an impromptu art history lecture from a guy who makes airplanes for a living. While the rich leggy hollow-cheeked blonde laughs quietly to herself and stares at the ceiling.

So here we see Richard Stark doing what he does–rattling Parker’s cage, testing his reactions, taking him out of his comfort zone. Parker just wants to do like he did in The Man With the Getaway Face–over and over and over–let him hijack an armored car here, steal a payroll there, and he cares not who writes the nation’s laws. Not like any of them are written for his benefit. But much as he (and we) enjoy that routine, it’s too simple–Stark wants to mix things up, keep Parker hopping, find out how he deals with matters he’s not accustomed to–like international espionage. But not the way Ian Fleming writes it. Not the least tiny bit like that.

Parker and Handy have inadvertently stumbled onto a much more complicated situation than they had bargained on, as Parker learns after he rescues Handy from two Outfit guys who are working with a member of the secret police of Klastrava, a tiny central European nation under Soviet sway. There is, you should know, no such place as Klastrava, in central Europe or anywhere else, but Westlake loved to make up his own countries–I may commission an atlas someday. Or possibly a google map.

The policeman/spy is a short, chubby, and utterly charming fellow, whose name is Auguste Menlo (which is not, best as I can tell, a name one would find in central Europe–it’s actually an anglicized version of an old Irish name, and I’m guessing Westlake lifted it from Menlo Park, New Jersey). He has conned a local branch of The Outfit into working with him. He had previously conned his own government (and perhaps himself) into thinking he was incorruptible, so they sent him on a special mission to America. See, the the diplomat with the statue (named Kapor) also has about $100,000 that he embezzled from the Klastravan government, which is hidden in the same place as the statue Mr. Harrow covets for his collection. Menlo is to liquidate Kapor and return the money–in that order.

Menlo had heretofore lived a life of unblemished Marxian integrity, faithful to his plump pleasant wife, never taking a bribe, sniffing out the non-orthodox (then snuffing them out), acting the part of a not-so-grand Inquisitor, up until the moment he found out he could become a rich man in America, at which point he immediately decided to hell with Marx, he wanted some capital of his own. He’s going to try playing some new Engels, har-de-har-har.

There is a kind of man who is honest so long as the plunger is small. This kind of man has chosen his life and finds it rewarding, so he will not risk it for anything less rewarding. And while Menlo had long since lost all interest in his Anna, the occasional woman who became available seemed to him hardly much of an improvement, certainly not worth the risk of losing his comfortable home. Nor were the financial temptations that cropped up along his official path worth the comfort and security he already enjoyed. As time went by, his reputation grew, and so did the trust it inspired. Who better to trust with one hundred thousand dollars, four thousand miles from home?

Who indeed? Finally faced with real temptation, Menlo’s carefully constructed identity instantly crumbles away, revealing his true identity–a thief and a rascal, loyal only to himself. But at this new avocation he is an amateur, though chillingly professional in other respects. And since he can’t take the money for himself if he goes about his job in the expected manner, with his officially sanctioned confederates, he needs to enlist the help of true professionals in this new field of crime that he is entering–he tries the organized gangsters he’s heard so much about, who have some helpful connections, but are otherwise a bit of a disappointment.

Then he has a series of encounters with Parker and Handy on their parallel mission, who fall afoul of Menlo’s group, forcing them to eliminate both the Outfit men and the Klastravan spymaster who was about to execute Menlo for his disloyalty. There’s a lot of torturing going on in this section of the book, by both Parker and the opposition, the difference being that Parker doesn’t enjoy it (Handy neither, since he’s one of the people being tortured at one point).

They learn about the 100 g’s from Menlo, who learns about The Mourner from them–and unlike them, he actually gives a damn. Something of an art buff, is our Mr. Menlo. How very bourgeois of him. Anyway, they strike a deal, which neither side intends to honor–Parker and Handy will keep him alive long enough for him to tell them where the money is. They expect him to try a cross sometime after they make their escape. He decides to do it a bit earlier than that.

When they break into Kapor’s art room at the ambassadorial mansion, he is most disparaging of Kapor’s miscellaneous collection of statuary, sniffing that such lack of taste deserves no one hundred thousand dollars (and in this we learn that he is not, like Parker, amoral–no truly amoral man ever used the word ‘deserve’ in earnest).

Menlo is grateful in his own way to Parker and Handy for their help, but has no intention of splitting ‘his’ money with them, and recognizes that they are too dangerous to keep alive a moment longer than necessary. When they are distracted by the cash he’s produced from a hollow sculpture of Apollo, he produces a deadly toy he’d concealed from them–a Hi-Standard Derringer, firing only two shots. He makes both of them count, leaving the startled heisters for dead, as he makes his exit, with the loot and the statue. He only had two bullets, and he does have to make his exit quickly, but still–he should have made sure they were dead. He’s so enraptured by his own prowess, the stunning early success of his new identity, that he fails to do so.

(I’m not a gun person, but damn that’s a neat little gizmo).

It should be pointed out that this is the second time Handy McKay’s affable nature, the one thing he does not share with Parker, proves a source of danger to them both–when Menlo wanted to grab his shaving kit, where the derringer was concealed in a false bottom, Parker had been disinclined to oblige, but Handy said what’s the harm, which turned out to not be a rhetorical question. Just as in The Man With the Getaway Face, Handy had given Stubbs a flashlight to light up his basement prison, which Stubbs then used to free himself. In the world of Richard Stark, it is literally true that no good deed goes unpunished.

So now we enter into a whole section of the book where Menlo is the POV character, and we follow him on his hastily improvised trip from Washington DC to Miami, where the Harrows are waiting for the Mourner, using the getaway car his presumably deceased associates had so thoughtfully provided. Bett Harrow has already invited him into her bed once (much to his astonishment), after Parker, in his “no sex, I’m working” mode had refused to service her needs (much to her astonishment), and he’s looking forward to repeating that experience.

It’s a very enjoyable section of the book, and it shows why Westlake had to become Richard Stark in order to write about Parker (and why when he couldn’t summon Stark’s voice, he had to stop writing the books for many years). Stark is, you might say, multi-lingual–he can get into Parker’s head, interpret his strange mode of thought to us–but he can also understand a man like Menlo, sophisticated, urbane, driven by more conventional human hungers.

Writing as himself, Westlake can appreciate a man like Parker, be fascinated by him, but can’t really understand him. Writing as Stark, he can temporarily shuck off his usual moral parameters (which are always there, even in his bloodiest books–especially in his bloodiest books), and just go with the flow, appreciating each character’s unique perspective, without necessarily sharing any of them. Though you can’t help but think that Stark thinks Parker’s way is best. And he wishes he could share fully in it, but somehow he can’t–Stark describes The Mourner to us, and we know–it’s not just sixteen inches of alabaster to him. Stark is midway between Parker and the rest of us, making him the ideal chronicler for both Parker and the people Parker works with–and against.

There’s a recurring theme in Westlake’s work (writing as Stark or himself), which I’d best mention now–you have to watch out for amateurs. They will catch you offguard, do what you don’t expect, and often win the day, or at least a skirmish, through sheer unconventionality. But they have their limits–professionalism is the key to a long successful career, in any field of endeavor. And the one thing a professional thief knows first and foremost is that too much improvisation is going to backfire on you, sooner or later–another is that you need to know the territory you’re working in. Menlo is entirely improvising, and he’s now deep into terra incognita, as he drives through the American heartland.

One thing after another goes wrong for him–he gets caught in a speed trap (something he’d never even heard of before), and has to kill a small town policeman to make his escape. He realizes more and more that he’s out of his element, not merely in terms of being a stranger in a strange land, but also in that a lifetime in the Klastravan thought police has ill prepared him for this new life he’s entered upon, in which he is no longer part of a political machine, but a free agent, with no organization to fall back on. His job was not merely a livelihood–it was who he was, and now he’s separated himself permanently from that, and from everything else he’s ever known. He’s become a stranger to himself. You don’t have to read every book Donald Westlake ever wrote to know how this journey is likely to end.

He reaches the Harrows, and makes a deal with them–The Mourner in exchange for assistance in creating a new identity for himself in America–he also needs to get a now unnecessary suicide capsule in his tooth removed. What he doesn’t realize is that Bett, who once again willingly accepts him as her lover, has told her father to promise him anything–then turn him in to the Feds once the statue has been handed over. He never does learn that American capitalists can be just as cold-blooded as his former colleagues, because when he returns with The Mourner, he finds Parker waiting for him in Harrow’s hotel room, gun in hand–and turns out that suicide capsule comes in handy after all. The amateur’s lucky streak has run out.

Then the story rolls back, and we see what happened to Parker after Menlo’s over-hasty exist from the art room. Handy is near death, but Parker was only grazed. He braces Kapor, who is suitably frightened to learn of his narrow escape. Parker offers to get back half of Kapor’s money from Menlo, in return for a doctor for him and Handy (and of course the other half of the money).

This is the second time in the book that Parker has gone out of his way to save his partner, and we’re going to see this kind of loyalty from him in the future–and never quite be sure what triggers it. Parker agrees to pay for a hospital for Handy out of his half of the 100k, and just for one startled moment we’re reminded of the Good Samaritan–later, when Handy survives, Parker says he can pay the bill out of his half, which almost comes as a relief–but the enigma of Parker’s selective altruism remains, a mystery that will never be fully solved.

Handy asks what Kapor said when he found out The Mourner was gone–Parker realizes Kapor, who has now absconded with his diminished bankroll, with Menlo’s colleagues hard on his heels, never even noticed the statue was gone. You wonder if somebody will someday steal the statue from Harrow, and whether he’ll meet the same fate as some of its past temporary owners. And you wonder if Harrow, for all his desire to possess The Mourner, really understands it, and the impulse that created it, any better than Parker. Certainly not as well as Richard Stark.

The main identity puzzle of The Mourner is Menlo, but we’ve been presented with a second conundrum–why is Bett Harrow so eager to offer herself to Parker, who she knows to be a thief and a murderer–and then Menlo, who she believes, briefly, to have murdered Parker. Parker, to be sure, has been shown to be attractive to most women he meets, but Menlo is by no means similarly gifted. And atypically, Parker himself gives us (and her) the answer–she’s attracted to strength. Which she defines as winning–by fair means or foul, doesn’t matter.

She feels no attachment to the men she beds, she doesn’t care what they look like or how good in bed they are. She’ll betray any of them when it suits her, but she needs them to be strong, dangerous in some way, to satisfy some secret yearning in herself, and in her privileged world, a good man is really hard to find. Parker, now in post-heist mode, his wounds forgotten, tells her he’s got a few hours to kill, and then she’ll never see him again. He walks into the bedroom, and she follows him, seemingly in a daze. A classic noir blonde of the deadliest variety, who would have spelled doom for the common run of hardboiled hero, has finally met her match–and lost him.

I guess you could say there’s one more identity crisis to be resolved here, and that’s Handy’s–he’s been putting it off, caught up in the events of the past three books, but when Parker visits him in the hospital, he says he’s finally ready to retire to his diner in Presque Isle, Maine. He says Parker should drop by sometime, and he’ll flip him an egg. Parker will never drop by, and they both know it.

Handy only plays an active role in one more Parker novel, and his absence is sorely felt, but there are reasons why Westlake is retiring him so young. He’s too much like Parker, differing mainly in his more easy-going nature. The only mystery to Handy McKay is why he stayed in this racket so long. He likes the work, he’s extremely skilled at it, but he seems temperamentally unsuited. We’ve seen it in these small acts of compassion that have cost him and Parker dearly.

He’s never going to be a fully honest man either, and his compassion has its limits. Menlo, contemplating his impending betrayal of both men, has a moment of exceptional insight when he inwardly refers to the two of them as “the most lupine of wolves.” But for the present, Handy is going to try being at least a semi-honest citizen. Just to see what it’s like. Parker has no interest in being anything other than what he was born to be. And that’s why he’s the strongest of all.

And in the next book, his strength is going to be tested like never before. Art may mean nothing to Parker, but he is nonetheless an artist after his own fashion, and when we return, we’re going to watch him paint what might well be called his masterpiece. With a most fascinating group of collaborators.

The Mourner is another letdown after two first Parker novels. For me, it’s not that good mainly because the plot is a little shaky. One man against the Mafia is OK, but that foreign intrigue stuff – it balances on the edge of the comedy. Menlo is a laughable character, he’s not a real threat to Parker. Still, the part written from Menlo’s POV is enjoyable. Foreigner on the American land, that’s a ready ground for possible social criticism and humour. (Reading Menlo’s part, I put myself in his place often: how would I behave there?)

Stark considered The Jugger his worst work (I don’t agree with that), because Parker behaved out of character. That’s not true, of course, though in The Mourner he acted out of character. When Parker saves Handy, we may consider that like out of character. There was not a strong reason to save Handy, to not leave him for dead. Yes, that’s loyalty. Pretty strong royalty, I’d say. Stark showed us human side of Parker, for better or for worse. I hadn’t though of that when I first read the novel, but now I think of that more and more.

While these are legitimate criticisms, and there is a case to be made that the Parker novels feel less ‘real’ when they stray away from the basics–ie, common garden variety armed robberies that actually happen all the time–we should realize that espionage is also going on all the time, all around us. It just doesn’t get reported in the papers very often.

Menlo is just so damned enjoyable–I go between imagining him as Walter Slezak (who was too tall to play him, but otherwise ideal) and a present-day American comedian name of John Hodgman, who I feel sure could do a perfect Klastravan accent. You can’t help liking him, even after he blithely confesses to murdering poor Clara so she can’t tell Parker where the money is. It’s hard not to like an unapologetic cad. Westlake will do something with that fact in a book I won’t be getting to for some time.

I couldn’t find a place in the review for my favorite quote from the book, so I’ll put it here–Menlo is explaining his former occupation to Parker and Handy, and says “I am, in my own way, a policeman. Not precisely the sort you two have undoubtedly encountered at one time or another in your careers. My occupation has no true counterpart in your country, except unofficially, among the members of some stern-jawed American society or the more belligerent American Legion posts.” The more things change, the more they stay the same.

Menlo is certainly far more formidable than Mal Resnick–he’s one of the few of Parker’s opponents to come close to killing him (Menlo doesn’t need to use a proxy), and in “Flashfire”, we see Parker looking at the scar Menlo’s derringer left on his body, and remembering him with what almost seems to be grudging respect. He never seems to give Mal another thought after strangling him. I doubt he ever gave Bronson much thought either after the events of “The Outfit”. They were nothing. But Menlo–something about Menlo stuck with him. That’s what Westlake seemed to be saying, anyway.

Probably the one thing that makes Menlo so dangerous is that he’s an easy man to underestimate. He doesn’t look like much, just like that funny little gun of his, but sometimes size really doesn’t matter (and sometimes it does).

There are weaknesses in the book–and one gaping continuity error–we’re told at one point that where the book picks up at the beginning (the night those two derelicts enter Parker’s hotel room, and Handy is being tortured), it’s been two months since Parker agreed to steal The Mourner for the Harrows–it’s clearly been more like two weeks, going by what we’re told about the events since that time. Westlake was writing these books awfully fast, and maybe that was just an honest mistake that no editor at Pocket ever caught–or maybe, as I’ve sometimes idly speculated, he made mistakes on purpose. Like the Navajo rug weavers who don’t want to anger their gods. Westlake had a superstitious streak in him, I often think (maybe I think that because I’m a bit superstitious myself–a certain type of mind sees patterns everywhere).

I think that when you look at the three books that immediately followed “The Hunter”, what sticks out is that they’re written very quickly, and that Westlake is using them to establish Parker’s character, build up a cast of characters, work out the general outlines of this new franchise, and tell an extended story that will hook people in (since the books are appearing only a few months apart from each other). Parker never really settles down and takes a solid six month break until after the events of “The Mourner” have concluded. Westlake may have concluded that he had to back off just a bit from the continuing storyline, before the series became too plot-heavy.

I don’t hold a serialized book to quite the same standards as a standalone. That being said, it isn’t one of my favorites, but I still enjoyed the hell out of it, the first time I read it, and when I reread it for this review. I’m also very glad that it’s fairly unique within the series, though “The Handle” has some of the same elements to it.

Parker saving Handy–and later, Grofield–it does feel like loyalty. But Parker would never call it that. If he’s not sure, how can we be? But ask yourself–how would we feel about Parker if he left these men who have been square with him right down the line in the lurch? Would we still feel the same respect for him?

Remember what I said–Parker is allowed to fail sometimes–he’s not allowed to look bad, ever. He’s also not allowed to do anything we’d see as ‘good’ for purely ethical or emotional reasons. He does what he does because he can’t do otherwise–even if he wants to. Westlake wants us to be a bit confused about Parker–he doesn’t want us to always know what Parker is going to do in a given situation. And furthermore, Westlake himself may not always have known what Parker was going to do, until he wrote it.

I have an idea about why Westlake was so dissatisfied with “The Jugger”, but why don’t we save that for a few more weeks. This much I will say–the rest of us make choices, good and bad–but Parker IS his choices. He may not always know why he’s behaving the way he does, because much of his behavior is instinctive, and he comes up with reasons for it after the fact.

He can’t be other than what he was born to be–a wolf in human form. A wolf doesn’t abandon his pack mates if he’s got any choice at all in the matter–and since he was born into the faithless world of man, his pack mates can only be the handful of men he works with–the few men that he trusts–and only while he’s working with them. He wasn’t born to be a hero, but he also wasn’t born to be a heel. Richard Stark simply won’t let him be that. Because Stark is a romantic–strange as it seems, given the rotten world he writes about, he’s writing about ideals. That’s the only answer I can come up with. It’s probably wrong, but it’s all I’ve got.

Parker’s not allowed to look bad, with that I’d agree. It doesn’t prevent the fact that Parker sometimes acts stupid, he’s not a machine. More that that, Parker not only sonetimes acts stupid, he IS stupid. I mean he’s street-smart, criminal-sort-of-way-smart, he’s not dummy. But is he smart? I think, no. He’s not educated, he can barely write, he’s almost illiterate. You can’t call a wolf smart.

That leads us to the third person narration. It maybe would be impossible to write Parker first-person. What happens in his head? Does he even have stream of conscienceness? Westlake would have trouble to describe some things from Parker’s point of view. Yes, third-person POV is close to first-person here, but it is still third-person. Take art, for example. Westlake can describe art, Parker can’t. Parker robs rock concert. Parker woudn’t know that it is ROCK concert. He doesn’t listen to music, he doesn’t know music genres. Westlake would have serious trouble if he wrote from Parker’s POV.

It’s fascinating that Parker is so unconcerned with things that basically all humans are interested in, to some extent or another. It tells us this is a truly unique individual, gives him a very singular mystique. But yeah, it does limit what you can do with the character. You certainly could not write 24 books entirely from his POV–but when you compare and contrast him with similar yet at the same time fundamentally different people–that works. Like I said, comparative psychology.

While in one sense Parker is the ideal none of these other people come up to, we should remember that’s because nearly all these people have chosen a life of violence and plunder. A wolf is a better hunter than a man. A man left alone in the wilderness with no tools is probably going to die. And the few humans who would live in that situation would hardly be considered the most intelligent among us.

Wolves and coyotes are extremely intelligent, as evidenced by the fact that they still exist after all our efforts to exterminate them (coyotes are actually more common in North America now than they were a hundred years ago). We have an enormous edge over them in terms of technology and numbers, and in some places they can still outmaneuver us. I wouldn’t want to pit my brain against a wolf’s in the wild. Not without a gun, anyway. If the wolf had a gun too, I’d start writing my will.

Intelligence may be the most subjective thing there is–I know to my dog, I appear a perfect idiot at times. There’s a hunting section in “Anna Karenina” you may recall where Tolstoy gets into the head of Levin’s dog Laska, who unlike her befuddled master, knows exactly where the snipe they’re seeking are located, and she’s trying as best she can to compensate for her master’s inadequacies, which cause her no small anxiety. In this specific instance, she is smarter than Levin, who is an exceptionally intelligent man.

Tolstoy was astoundingly brilliant, one of the outstanding brains in all of history–and where did that intelligence finally lead him? Into a blind alley of philosophical and religious excess. We can get lost in the maze of our own minds, if we’re not careful. The more complex a machine, the more easily it breaks down.

Intelligence is best described as a tool, and a tool that is brilliantly suited for one pursuit may be hopelessly unsuited to another. Parker is, you might say, a genius at what he does, and he doesn’t want to do anything else. To be supremely good at the only thing you want to do is, to Richard Stark, as good as it gets. To Westlake, it may not be that simple, but at times I think he wanted it to be, and that’s where Stark came from.

I enjoyed The Mourner very much. This is a change up from the previous three Parker novels, for sure. Art is injected into the mix. Also, we have three well-educated, articulate characters who talk a lot (way too much for Parker’s liking) and two of those men from Eastern Europe. Those parts with Menlo and Kapor are real highlights. Such an extreme contrast from Parker. BTW, the speech of Menlo reminds me of VN’s Charles Kinbote (Pale Fire) from the Eastern European country of Zembla.

Since one of my prime interests is art and aesthetics, I particularly was taken by your accurate observation – “Art has absolutely no meaning to Parker. It does not exist for him. The Lost Mourner of Dijon might as well be a garden gnome from Walmart, as far as he’s concerned. He’s not a philistine, because a philistine has bad taste. Parker has no tastes of any kind when it comes to anything other than women–he’s not all that picky there in a pinch. Art is only meaningful to him as a potential source of income.”

In addition to having a discriminating taste in women as you point out (he rejects the young, dumb fatty at the end of the Outfit; better save himself for the good stuff – Bett), I recall at some point Parker enjoying a good steak dinner. In other words, although art has no meaning for Parker, certain everyday aesthetic experiences like good women and good food do.

I don’t know as I’d agree Bett constitutes ‘the good stuff.’ An interesting diversion, at most. Parker certainly feels attracted to her, but then walks away from her–her physical attributes are not enough to make up for a shallow flighty treacherous nature. In a typical noir film, the hero would be dragged under by such a blonde, but Parker marks her down as trouble, leaves her without so much as a backward glance. He remembers Menlo, briefly, years later. Not Bett.

And I don’t think specific body shapes really matter that much to him–or natural hair colors–when you get to The Rare Coin Score, you’ll see what I mean. (Forget if you said you’d read that one already.) A good lay is a good lay, and he isn’t really that picky when his hunger is aroused. Remember, he hadn’t just pulled a job. He was working on one. He would have been indifferent to just about any woman.

Ethel, the girl who works for Madge in The Outfit who has eyes for Parker, is described as retarded (not a PC term now, but what term for that type of disability wouldn’t become an epithet eventually>), and that’s the problem. Physically old enough, but not mentally. Parker doesn’t date kids. Not out of moral qualms. It just wouldn’t work. Starkian morality. And suppose she decided, with her child-brain, that he was her property after that? The Green Glen motel is a useful resource to him. But again, he’s just not interested in sex at that point. Wouldn’t matter if she was Jane Greer.

Parker has to view even his short-term hook-ups through discriminating eyes, because he’s making himself vulnerable every time he takes a woman to bed. We’re all another species to him, always remember that. A species he can never fully trust. Man, woman, black, white, straight, gay. Alien. Other. And even the best of us, just a bit crazy.

Take a gander around you. Is he wrong to think that?

Parker is surely no aesthete. Is he a sensualist? Nah. He’s just sensual. When he lets his guard down enough to enjoy his senses, instead of using them to survive. No ‘ist’ will ever stick to him. Because he’s not crazy. Except when you cross him. And that ends when he crosses you off his list.

All spot-on observations. I agree re Bett, particularly after events in The Mourner. I used the language that I used since I read “The first one after a job ought to be a good one, like Bett, not a pig from Scranton.”

Parker is surely no aesthete — You got that right!

Yeah, ‘pig from Scranton’ is a rare false note from Stark, but Parker himself doesn’t always know why he does what he does, or doesn’t do what he doesn’t do.

Westlake was still new to the character, still working out the kinks, using well-worn tropes from the genre he at times had very mingled feelings about (see Adios, Scheherazade). In the later books, you don’t get that kind of language from Parker, even in the depths of his mind. Parker gets less human, more lupine, with every book.

Now THIS is an installment I have plenty to talk about!

First off, the little things. The torture and eventual death of Clara always stuck with me after my first reading, and upon a reread, it still packs a punch. I think what makes it so effective is how vague it is. We’re only given one concrete fact: Whatever the hell Parker did to her, it involved matches. How long did he do it? How far did he go? That’s for us to decide. It’s true we’re also told Parker fucked her up so badly that she had to be mercy killed, but considering that was said by Auguste Menlo (a man who would benefit greatly from her not living), even this is up to interpretation.

Another little thing that stuck out to me was the ending. Not only is the final line a great closer to a great book, I find it similar to the ending of The Seventh (speaking of installments I have a lot to say about). I feel they both have this cosmic payoff the universe decided to give Parker, a perfect capper for all the bullshit he went through in both installments. Or maybe it’s the laugh, I dunno.

Yet another small thing that stuck out to me: the double cross Parker and Handy planned to pull on Menlo. I find it fascinating specifcally in how it compares and differs from the double cross of the Hunter. Like in The Hunter, Parker plans on double crossing someone for more loot, something he normally never does. However, THIS time the man he’s double crossing had already fucked with Parker by kidnapping Handy and sending other thugs to his hotel room before they decided to begrudgingly team up for the hundred G. So it feels to me that Parker’s crossing Menlo not just for more loot (though the money is a primary factor) but also as payback for Menlo having thrown the first punch.

Speaking of though, let’s get on to the big stuff (pun not intended), starting with Auguste Menlo, the lovably unscrupulous cad. It’s almost a shame the Parker series never really did recurring individual antagonists, because Menlo was a crackerjack villain. He has such a charmingly goofy presence that he effortlessly weaponizes. In many ways, he’s a perfect foil to Mr. Harrow. Both are utter romantics, willing to perform shady actions to get what they desire. But Menlo’s not only more honest in regards to his dark side (he outright admits to himself that he only resisted temptation for so long because he hadn’t truly encountered it, whereas Mr. Harrow probably still considers himself an honest and good man), he’s also more confident in his affinity for romance. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Parker was able to shut Harrow up but had to play along with Menlo’s romanticism. I could easily imagine Zero Mostel killing this role in a dream adaptation.

Finally, let’s talk about Handy McKay, Parker’s first sidekick. I’ve kind of put off talking about him because y’all have pretty much said everything great about him. He’s just a cool, laidback dude who’s loyal, sometimes even compassionate, and someone who just wants to run a diner in Maine. It’s like you said in the review for The Man With The Getaway Face, he’s perfectly ok with being a sidekick. Of course, that’s not to say he’s harmless. In a way, Handy’s also like Menlo. They both have affable, even lovable, personas that hide a more ruthless and dangerous personality. Unlike Menlo though, Handy knew just when to quit (well, aside from Butcher’s Moon apparently but I haven’t read that one yet). For casting choices (because I love hypotheticals), I imagine either Paul Rudd or Ethan Hawke. Both are at that age of “men with grey in their hair who keep pulling one last job after one last job” and they both have a chill, laid back energy they usually give to their performances. They’re also both very good at playing the “co lead” in movies, Hawke in particular. Neither are very tall, granted, but I’m not really a girl who cares about height anyway.

As for Parker’s selective altruism, I have a theory. Leaving a fellow heister to get arrested? Oh they’ll live, maybe even get their shit together while in prison. Making them pay to heal their own injuries? Only fair, really. But outright leaving someone for dead? Well Parker himself was left for dead, by someone he trusted, even. Maybe that has nothing to do with him saving Handy, but I think it’s an interesting coincidence nonetheless.

All in all, a truly fantastic entry in the Parker series. Now if you’ll excuse me, I’m gonna prep myself for The Score…and the scorched battlefield that is the comments section for the The Score review.

I’ve long felt it’s an underrated book in the series. To me, as I’ve said, the best part is learning that Stark is a legit art lover (as opposed to a mere collector, like Harrow), but Parker doesn’t even know what art is good for, except sometimes you can get money out of it. This underlines that Stark has a worldview quite distinct from Parker’s, and that even he only partly understands the way Parker sees the world. Omniscient, but only with regards to what happens, not always why.

I don’t believe anything Menlo says about things that happened when Stark wasn’t around to describe them. Parker, of course, doesn’t care if Menlo is telling the truth or not. If Clara is dead, it’s none of his affair, unless it could somehow be pinned on him by the law, and Menlo just confessed to killing her. (Bragged about it, really.) Obviously if Parker left her alive, the most she needed was medical care for burns, and Menlo didn’t want to risk her talking.

Parker was going to kill Mal in The Hunter because he could smell a cross coming, but wasn’t sure how and when it was going to happen. I’d assume it’s similar here, but again, he waits a bit too long. And again, the crosser doesn’t check to make sure there’s no pulse. And in both cases, it’s been set up so that doesn’t feel contrived, even though it is.

I was torn between Walter Slezak and John Hodgman for Menlo. I love Zero Mostel far too much to ever cast him in a role where he has to die. The Trickster Incarnate. Did you ever see his Gianni Schicchi?

It’s interesting to me that Handy seems to have known all along Parker would come for him. Even though in Butcher’s Moon, he says–well–that can wait.

When I reviewed The Outfit, I only had one reader piping up in the comments section. He’s Russian. (It wasn’t out of vogue at the time). We still argue all the time, but mainly via private email. We agree about the important things, like Putin being an ass. It’s safe to go into the comments there. No bullets flying. For now.

See, I’m not entirely sure on that. Menlo offers a small percentage to Parker and Handy, to which Parker demands a bigger cut, while inwardly musing that Menlo wouldn’t be getting a single cent anyway. Menlo immediately agrees to the cut increase, which leads Parker to quip something along the lines of: “Ok, so he’s planning on a double cross too”.

That suggests to me that he’d already planned on crossing Menlo, regardless of Menlo’s intentions.

Parker acts on instinct a lot. And his instinct says don’t trust Menlo. A string member you can’t trust needs to be dead. That’s the same reason he was going to kill Mal. It’s not based on anything concrete. Just an itch in his head that needs to be scratched. This is typical of the early books. He’s a bad guy fighting worse guys.

Later on, Westlake seems to have decided Parker’s ‘code of ethics’ wasn’t so flexible, and you had to give him a clear reason to bump you first. Remember, the first novel was written with the idea that he would pay for his crimes at the end, after making some other bad guys pay first.

Something of that dastardly ethos of the first book made its way into the next three, which Westlake wrote in very quick succession, to fulfill the agreement he signed with Pocket, thanks to Bucklin Moon. Moon loved The Hunter enough to call Westlake in and say they wanted a whole lot of Parker books really fast (ultimately, a rate of production he couldn’t sustain long), and Westlake is not going to look that gift wolf in the mouth. He’s going to give this very important reader what he’s asking for, in spades. His initial audience for the series, in a very real sense, is Bucklin Moon. At least until he starts seeing sales figures, and receiving fan mail. Moon, who was to all accounts a deeply moral person, enjoyed Parker’s amorality enormously.

Over time, Parker got more–I want to say refined, but that ain’t it–restrained?–nah. Regulated? Try again. Definitely not repressed. Reactive. You have to provoke him for that button in his head to be pushed. This strangely passive trait of his there, latent in the first novel, but Westlake is still figuring out the rules over the next few. And, of course, will never share them with us. We have to infer them from what happens, and what doesn’t.

But if you have to rationalize something that can never be fully understood (or Parker wouldn’t be so interesting), Menlo treating Parker and Handy as employees, instead of fellow string members–he just doesn’t understand how they think. He’s a spymaster. To him,this is how you do a job. You get some assets, control them by various means, dole out rewards sparingly, keep them on the hook.

Again, a study in contrasts. Menlo may have abandoned his employers, but not his tradecraft. He’s still the same animal he was before. Incapable of understanding the kind of animal Parker is. Until it’s far too late.

I definitely agree about the difference between Bastard!Parker of the early novels and Reactive!Parker of later installments. However, I think the cross in The Mourner represents a sort of bridge between the two incarnations.

Like you said, The Hunter’s double cross was pure instinct, Parker got a bad feeling about Mal and had to snuff him out. It was a ruthless move from a ruthless wolf who wasn’t supposed to survive.

Where the Mourner differs is that Menlo had already proven to be, at best, a pest to Parker and Handy. He had kidnapped Handy and most likely planned on killing him once the information had been extraced, he shot at Parker during their first encounter, and (as you said) practically bragged about killing his henchwoman. That last part isn’t to suggest Parker cares about Clara’s death (he doesn’t), but I’m betting he was thinking about it when Menlo said he would totes let Parker and Handy have a percentage of the 100k.

You yourself said that Westlake was still working out the rules of this character in the early works. I think this is his first stab at moving Parker away from that initial bastard incarnation and into the more reactive state of later books.

To some extent, they’re all transitional books. That’s why the series never feels stale. Not a retread in the bunch. He might come at the same idea from a different direction sometimes, particularly if he thought he didn’t get it right. But The Mourner really stands alone–Parker going after a unique objet d’art for a buyer.

Of course, The Mourner is coming at The Maltese Falcon from a different direction. No question at all, Spade is one of the major influences on Parker, occupying a similar niche in Westlake’s rogues gallery to Spade in Hammett’s. A ‘Dream Man.’ But without the nagging conscience. And he’s not telling any Flitcraft stories. (Well, neither did Bogie in the Huston flick). No Effie, either–she’s Spade’s conscience, so obviously Parker doesn’t have an Effie. Unless you count Madge? More like a superego. And too rarely seen.

While there’s no surpassing Hammett’s standalone masterpiece, the problem with Spade is that he didn’t have a second act. Parker could never be used up.

Since we’re dream-casting, I’ve always pictured Sydney Greenstreet as Menlo, mostly because I get a Maltese Falcon vibe from the whole dizzy affair.

I don’t think an English accent works for Menlo, plus Greenstreet was too old for the part by the time he started doing Hollywood films. Harrow is really the Gutman in this narrative. Menlo is more of a Cairo, but not gay. And yeah, Lorre could have played him pretty well. The Austro-Hungarian accent would work. Has to be something Central European.