Holding the mask out from his mouth with his free hand, Kelp said “Let’s not scare the kid. Nobody’s gonna get hurt.” It was a line word for word from Child Heist, which Kelp had been rehearsing for two weeks now.

According to the book, the chauffeur was supposed to ask Kelp what he wanted. Instead of which, Van Gelden pointed at the pistol and said, “Scare the kid?” Then he gestured a thumb over his shoulder and said, “Scare that kid? Hah!”

This book enjoys a rather unique distinction among the Westlake canon. In 1978, Westlake’s good friend Brian Garfield (who I talked about in two recent articles here) published an anthology of pieces in which crime fiction writers described personal encounters with actual crimes. Westlake’s contribution was an imaginary account of him at a fashionable cocktail party, where the only food available is fancy potato chips, regaling bewildered onlookers with the story of how he came to write Jimmy The Kid. It’s funny, clever, and more than a touch convoluted, as the origins of popular fictions so often are. I strongly suggest you obtain, have you not already, a copy of The Getaway Car, and read this fascinating piece. Save me a lot of trouble, for one thing.

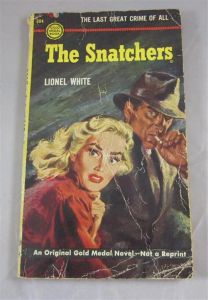

But perhaps you expect me to save you some trouble? Okay, the upshot is that the story of this book was inspired by the story of an actual kidnapping which was inspired by yet another book. Namely The Snatchers, aka Rapt, by Lionel White, a native New Yorker, who wrote a lot of taut suspenseful crime books, often published in paperback by outfits like Gold Medal, many of which became movies, and the movies were rarely very faithful to the books. Sounds familiar, huh?

(Westlake and several other sources refer to the book as The Snatch, but I can’t find any edition with that title.)

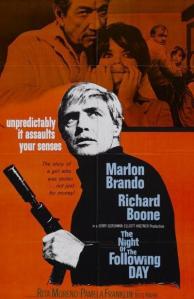

Like many another Lionel White outing, this one much later got turned into an exceptionally unfaithful film adaptation (with Marlon Brando, no less). But it is probably better remembered today for the fact that a pair of rather impressionable French criminals decided to use the Serie Noire translation of it as the blueprint for (successfully) kidnapping a toddler who happened to be the grandson of the head of Peugeot.

You know, Peugeot? Cars, bicycles, etc. The cars were never that common here, but Lt. Columbo drove one on TV. First car I can remember is my dad’s little dark blue Peugeot (don’t ask me which model, I was about the same age as the kidnap victim at the time). My mom later said it was his rebellion against adult responsibility, or suburban conformity, or something. You know how mothers are.

Not only was the boy not harmed (because the book specifically said not to do that), he actually seems to have had a rather interesting time–the elder Peugeots, having received some very threatening missives about what would happen to little Eric if they didn’t pay up, were not so amused.

And the kidnappers, not having had the foresight to get a book telling them how to behave after scoring big on a kidnap caper, threw their ill-gotten gains around like water, made snide allusions in bars regarding their daring enterprise, and they both went to prison in short order. Life may imitate art up to a point, but then comes Murphy’s Law. Or, if you prefer, The Dortmunder Effect.

The idea of adapting a crime adapted from a novel was not originally Westlake’s (in fact, it wasn’t even originally the French kidnappers’ idea; see The League of Gentlemen). He was approached by some film producers who wanted to do a story along similar lines. Not the Peugeot kidnapping, but something like it. Westlake gave it some thought, and wrote a treatment which tried to change the crime to counterfeiting, which didn’t work. So he changed it back to kidnapping, which reportedly worked better, but the studio head, a grandfather himself, didn’t see humor in the concept for some odd reason.

The movie was scrapped. But as had happened twice already in the past, Westlake had retained the book rights, and eventually decided (with encouragement from his then-girlfriend, Abby Adams) to try and turn the story of a kidnapping adapted from a novel back into a novel. Art imitating Life imitating Art.

(Anyway, as is mentioned in this very book, you can’t copyright real-life events. Anybody could do a story about the Peugeot kidnapping, or a story inspired by it. Even though it was itself directly inspired by a book that is, far as I know, still under copyright. Plagiarism laws only apply to fictional events and persons, not real events committed by real persons, inspired by fiction. Westlake thought this was very funny).

He’d been down this same exact road already, with Who Stole Sassi Manoon? That comic kidnapping caper was a creative failure, in spite of some good writing, mainly because the characters had poorly defined voices, perhaps because they’d been written as film characters who had to be played by popular film stars, and something was lost in translation between mediums. Here, he’d remake the story basically from scratch, and instead of using the characters from the two treatments he’d written for the movie that never got made, he’d use characters with very strong voices that he’d already featured in two previous novels–eighteen if you count Parker.

Yeah, this is the Dortmunder novel where Parker has a cameo as a fictional character in Dortmunder’s world, and Stark has a epistolary cameo as his pissed-off creator. That, I think, is how most people tend to remember it today, and that’s why a good first edition can run you a bit more than other Dortmunders from this general time period. Overlapping fanbases. But if you’re a Stark reader who ran out of novels and is hoping to find a new Parker heist contained in the pages of this book, you’re in for a disappointment. Because this isn’t really Parker, it’s only three chapters, and it’s not very good–the Parker chapters, I mean.

It only makes sense. If Westlake had come up with a really great idea for a Parker novel, he’d use it to write another Parker novel. Possible this is a rejected idea he pulled out of his Parker slushpile, but I don’t think so. We know where he got the kidnapping angle from. And we know something else–Parker–the real Parker–would never get involved in a job like this. Kidnapping isn’t his line. And kidnapping a child? Stark wouldn’t have it. But Stark’s not pulling the strings here. Stark’s taken a long coffee break (black, of course), leaving Westlake not really knowing how to write in that voice anymore.

I think there is some attempt to contrast the Westlake style with Stark’s here, but it’s not that effective, because as I explained a few weeks back, in the course of writing the hybridized Westlake/Stark epic that is Butcher’s Moon, he’d somehow slipped out of the groove, as far as Stark was concerned. It would be quite a while before he got back in that groove, and he’s faking it to beat the band here.

And that’s perfectly fine, because this isn’t a Parker novel–it’s a Dortmunder, and one of the better ones, I think. Not everyone agrees–it’s certainly not a classic of the series, since kidnapping isn’t Dortmunder’s line either, and for obvious reasons he’s not planning the job this time (much to his disgust)–but I was shaking with laughter at my local, as I finished it over tacos and beer. And I picked up on some things I missed the first time through. It’s a funny, insightful, and deceptively simple little book, with a lot of layers to it. And a fine addition to a rather odd little sub-genre–the comic kidnapping story.

I mean, kidnapping shouldn’t be funny, should it? It happens all the time in real life, and the kidnap victims and their families are rarely laughing about it. And yet something about it excites us–even the word ‘kidnap’ itself, which originally meant exactly what it sounds like–child theft. We all have some kidnappers in our family trees–just as so many of our great national epics are about armed robberies of some kind or another, as I explained in my review of The Score, you can just as easily go back through ancient mythology and find one long series of colorful (and often sexual) abductions.

Hell, that’s how Rome was reputedly founded, with those Sabine women, only they didn’t call that kidnapping at the time. But why is that story so unexpectedly funny, and later the source of a Hollywood musical comedy with great choreography? Because the women want to be abducted. Because they end up having a good time, and wanting to stay with their abductors. So that’s the secret to making it humorous, as opposed to suspenseful, or tragic. Turn the tables. Dramatic reversal.

The funniest kidnapping story of all time debuted in the Saturday Evening Post in 1907, and Westlake knew damn well he was never topping that one. The inner dust jacket for the first edition up top says otherwise, but it lies. Westlake came up with a splendid variation on a theme, make no mistake–but some things in this world can’t be improved upon.

How long since you last read it? It had been quite a long while for me, and I savored every paragraph, every last impeccably chosen word. As close to perfection as any mortal can get, but the message is very simple, isn’t it? “Boys are a lot more trouble than you think.”

Reading it as a child, you think “This kid is great!” Reading it as an adult, you realize your loyalties have somehow inexorably shifted, and you marvel at the stoic saintly patience of the kidnappers. You look at some banal Hollywood re-rendering of it, like those Home Alone movies, and you yearn for something heavy to fall on Macauley Culkin and put an end to his tow-headed malevolence (mercifully, adolescence eventually achieved the same result without the need to resort to bloodshed).

But from either generational perspective, it’s funny, because much against their will, the abductors have become the abductees. Because they could never really harm the kid, they are subject to being seriously harmed by him. And he has no intention of ever letting them go. They’re just too much fun. I think The Joker said that to Batman once.

Westlake said in that piece he wrote for Garfield that he didn’t want to use a child the age of Eric Peugeot at the time he was grabbed because an infant kidnapping is ‘inimical to comedy’–the Coen brothers kind of proved him wrong with Raising Arizona, but of course that was abduction for love, not money. And it had the aesthetic sensibility of a Chuck Jones Roadrunner cartoon. But it’s still the same basic idea–you create comedy in a story about a kidnapping by creating sympathy for the kidnappers. They did not know what they were getting into.

And in fact, Eric Peugeot said later he was fascinated by his kidnappers, entranced by them–he’d never been around two grown men so much before, let alone men of this class, and he watched them avidly. He was certainly scared at points–not traumatized in the least. But he was no real trouble to them, being past the terrible two’s, yet still too young to ask a lot of silly questions, or get up to any serious mischief (okay, I hear parents of three year olds objecting now, but he wouldn’t be trying to scalp them, would he?).

The only problem the kidnappers had was their own stupidity once the kidnapping was concluded. The kid was just quietly curious about them. Okay, that’s not funny, or at least not the right kind of funny. Need an older victim. Perhaps older than his years? Can’t make him too much like O. Henry’s kid.

P.G. Wodehouse did several stories about child kidnappings, but those were early works, before he’d arrived at the brilliance of Jeeves, Mulliner, Uncle Fred, or Blandings. His gift for comic language was developing rapidly, but his grasp of characterization and plotting was still in embryonic form. So those books have dated rapidly, and the kidnappings are treated rather offhandedly, lost in the shuffle of too many implausible story threads, and too much forced banter (like Who Stole Sassi Manoon?, only worse). Even Plum had to start somewhere.

If you’re going to tell a story like this, to make it funny you have to build on the logic of it, not just throw it in for a lark. So O. Henry, that most consummate of craftsmen, would be Westlake’s model here, not Wodehouse. Have to match the tool to the task. And now my tool had best be the plot synopsis.

Having repeatedly failed as a heister, Dortmunder is trying life as a mere burglar, going down a fire escape (there’s going to be a lot of those fire escapes) to break into a furrier’s shop, and then he hears a voice calling him from above–is it the Lord? No, it’s just Andy Kelp. (Interesting though, that Dortmunder, as opposed to Parker, seems to have some sort of half-hearted religious notions in his head, no doubt put there by the Bleeding Heart Sisters of Eternal Misery, who raised him as an orphaned youth).

Turns out Dortmunder was on the wrong floor of the building (he’s never going to be much of a burglar–made for bigger things), and to have Kelp point out his mistake adds insult to injury. Kelp opens the door of the shop for him, and he won’t even look at the furs on the racks–Kelp has ruined yet another job for him. He’s just doing to get into his stolen VW Microbus and leave. But their squabbling has roused the whole neighborhood, and they have to get out of there, and he accidentally bloodied Kelp’s nose in his wrath, so he lets Kelp ride with him. And this is a mistake of course. Because Kelp has an idea. Kelp always has some damn fool idea. But this one is weird, even for him.

With the hand that wasn’t holding his nose, Kelp reached into his jacket pocket and pulled out a paperback book. “It’s this,” he said.

Dortmunder was approaching an intersection with a green light. He made his turn, drove a block, and stopped at a red light. Then he looked at the book Kellp was waving. He said, “What’s that?”

“It’s a book.”

“I know it’s a book. What is it?”

“It’s for you to read,” Kelp said. “Here, take it.” He was still staring at the roof and holding his hose, and he was merely waving the book in Dortmunder’s direction.

So Dortmunder took the book. The title was Child Heist, and the author was somebody named Richard Stark. “Sounds like crap,” Dortmunder said.

Dortmunder takes the book, figuring what the hell. Kelp’s next errand is to go find Stan Murch and give him a copy of the same book–he tells Murch (whose reading is mainly confined to newspapers and car magazines) the guy in it will remind him of Dortmunder. And Murch also takes the book, also figuring what the hell. Kelp says to make sure Murch’s Mom reads it as well. What the hell?

Then Kelp shows up at Dortmunder and May’s apartment, along with Murch, to make the pitch. Kelp’s idea is simple–and not original to him, but how’s he to know about the French guys? See, he got pulled in by some cops out in the sticks a few days, a bum rap, they didn’t have anything on him, which isn’t to say he was innocent, but cops should know better than to put a crimp in a man’s schedule over a bad arrest. It’s unprofessional.

Anyway, the jail had a bunch of books donated by a local ladies club (heh) and a lot of them were these books about this armed robber named Parker, written by this Richard Stark person. You may have heard of them. Having nothing better to do, Kelp read the books, and was immediately captivated by the idea of a hardened criminal who pulls daring complex heists and never gets caught.

I already used the money quote from this chapter for my review of The Score (check it out, or just read the book), but basically Kelp is saying they should just do the plan from this book he particularly liked named Child Heist–which is about a kidnapping. Just follow the same plan Parker and his associates employ, right down to the letter, and it’ll succeed, like it does in the book. Why wouldn’t it?

He wants May and Murch’s Mom (she has a name, but it’s hardly ever used) to babysit the kid, which Murch’s Mom says is very sexist, while simultaneously conceding that Kelp and the other guys in the string would have no idea how to take care of a child.

May, who has no problem at all with crime as a modus vivendi, thinks it would be mean to frighten a little kid by taking him from his home and family. Murch’s interest is predictably limited to the wide variety of motorized vehicles needed to pull this job. Dortmunder says very little, brooding to himself, and then he suddenly says he never wants to see Kelp again. He’s furious. Because he’s the planner, and Kelp is bringing in this Stark guy, who probably never so much as knocked over a candy store in his life, as a ringer, to do his job! He’s been outsourced! And that’s not even a thing yet!

But as they all admitted earlier in the meeting, the problem here is that big cash scores are getting hard to find in this increasingly cash-free modern world (same problem Parker has been having in the dimension next-door). Dortmunder has no better options at present, and he hates living off May and her meager supermarket salary (that she steals most of their food from her employer is neither here nor there). He’s only really happy when he’s planning a big heist, and May knows that. She likewise knows that because of his past offenses, if he gets caught stealing so much as a pack of Luckies for her he’s going back to prison for life, so he might as well pull something big.

May is also concerned that Kelp is so obsessed with pulling this job that he’ll do it without Dortmunder, and something will go horribly wrong, and the kid will get hurt, even though nobody wants that. Somehow, hearing about this proposed federal crime has roused her maternal instincts. So she fixes Dortmunder all his favorite dishes for dinner, and works on him, like only she can. She explains to him that he’s still needed to make the plan in the book work in the real world.

“Kelp brings a plan to me.”

“To make it work,” she said. “Don’t you see? There’s a plan there, but you have to convert it to the real world, to the people you’ve got and the places you’ll be and all the rest of it. You’d be the aw-tour.”

He cocked his head and studied her. “I’d be the what?”

“I read an article in a magazine,” she said. “It was about a theory about movies.”

“A theory about movies.”

“It’s called the aw-tour theory. That’s French, it means writer.”

He spread his hands. “What the hell have I got to do with the movies?”

“Don’t shout at me, John, I’m trying to tell you. The idea is–”

“I’m not shouting,” he said. He was getting grumpy.

“All right, you’re not shouting. Anyway, the idea is, in movies the writer isn’t really the writer. The real writer is the director, because he takes what the writer did and he puts it together with the actors and the places where they make the movie and all the things like that.”

“The writer isn’t the writer,” Dortmunder said.

“That’s the theory.”

“Some theory.”

(Godard liked it well enough. You’re still mad at him, aren’t you, Mr. Westlake? Him and that Boorman guy who said he liked to exploit writers, steal their ideas, and then discard them. In public he said this, while adapting your book into a movie. A movie you kind of liked, but a movie that bombed. ‘The writer isn’t the writer.’ Sheesh. These new filmmakers got no couth. No wonder you’re so grumpy. As to what Dortmunder has to do with the movies, probably better not to ask, but for those who must know, read my piece Dortmunder At The Movies. On this very blog. And don’t say you weren’t warned. Back to the synopsis.)

So the gang all meet up at the O.J. Bar and Grill (this time the chatty barflies are two telephone repairmen about to get into a fight over the derivation of the word ‘spic’ to refer to Puerto Ricans), and Dortmunder grudgingly admits that the book could serve as a jumping off point, but it needs to be adapted. See, talking like an aw-tour already! And then we get a whole chapter of Child Heist, showing us Parker and some guy named Krauss scoping out potential kidnap victims. Here’s how the Parker chapter begins:

When Parker walked into the apartment, Krauss was at the window with the binoculars. He was sitting on a metal folding chair, and his notebook and pen were on another chair next to him. There was no other furniture in the room, which had gray plaster walls from which patterned wallpaper had recently been stripped. Curls of wallpaper lay against the molding in all the corners. On the floor beside Krauss’ chair lay three apple cores.

And here’s how the Dortmunder chapter begins:

When Dortmunder walked into the apartment, Kelp was asleep at the window with the binoculars in his lap. “For Christ’s sake,” Dortmunder said.

And this is a recurring theme of the book–that in Parker’s world, every job goes smoothly, everyone’s a consummate pro, nothing ever goes wrong–and in Dortmunder’s world, it’s the exact opposite. Westlake knew this was a rank oversimplfication–Parker, if anything, has worse luck than Dortmunder with his strings (only once would any of Dortmunder’s associates ever try to kill him), and he never once pulled a heist without something going seriously wrong, but here’s the thing–how can Westlake get that across to that very large section of the Dortmunder readership that has not read the Parker books? Who may in fact assume they’re something Westlake dreamed up specifically for this story.

It ruins the sly meta-textual joke he’s making here if he brings in all those inconvenient nitpicky details. So he doesn’t. But for those of us who have read the Parkers, this can be irritating. It’s still fun to read, mind you. But we know it’s wrong. It’s one of the less effectively executed gags, but still fascinating to read, for those who follow both series. I don’t think it’s really meant as a commentary on the Stark books. That’s not really what this book is about, contrasting Stark and Westlake, but it’s there, and it doesn’t quite come off, because Westlake can’t really write like Stark in this context. Fortunately, he doesn’t have to. There’s plenty else going on here. Layer after layer, joke within joke.

So going by the book, they have to scope out limos from a handy lookout spot. They need one with a built-in phone that routinely carries some rich kid to and from an appointment in Manhattan. In Child Heist, ‘Parker’ and his buddies find a Lincoln that fits the bill nicely–Dortmunder & Co. find a Cadillac. This leads to some confusion later, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

And the deceptively diminutive backseat occupant of said Cadillac is one Jimmy Harrington, twelve years of age, youngest son of a rich corporate lawyer, and boy genius. So much so that he’s going to a psychiatrist in the city, to work out some of the personal issues that tend to arise when you’re smarter than all the kids in your class, and probably most of the adults you know as well. Would it sound arrogant if I said I can relate? Yeah, it probably would. Never mind. But something tells me Westlake related a whole lot. In this specific regard, at least. It’s not a rich kid’s fault that he’s rich. It is, on the other hand, very much a psychiatrist’s fault that he is a psychiatrist.

Jimmy Harrington, lying on the black naugahyde couch in Dr. Schraubenzieher’s office, looking over at the pumpkin-colored drapes half-closed over the air-shaft window, said, “You know, for the past few weeks, every time I come into the city I keep having this feeling, somebody is watching me.”

“Mm hm?”

“A very specific kind of watching,” Jimmy said. “I have this feeling, I’m somebody’s target. Like a sniper’s target. Like the man in the tower in Austin, Texas.”

“Mm hm?”

“That’s obviously paranoid, of course,” Jimmy said. “And yet it doesn’t truly have a paranoid feel about it. I think I understand paranoid manifestations, and this seems somehow to be something else. Do you have any ideas, Doctor?”

Though he responds with more than “Mm hm?” this time, the Doctor seems more concerned with scoring a rare intellectual point over his precocious patient than in getting to the bottom of Jimmy’s actually quite well-founded anxieties. But you get the gist of the character here–Jimmy has a first-rate brain and tremendous intellectual curiosity, bolstered by extensive reading, and no doubt the best private schools and tutors money can buy. He seems to have no friends his own age, and this doesn’t seem to bother him much, but the boy could use some seasoning. Like a Captains Courageous kind of deal. Only tougher on the captains than on the kid, as matters shall arrange themselves.

Jimmy seems to me like a much younger and far less irritable reworking of Kelly Bram Nicholas IV, the main protagonist of Who Stole Sassi Manoon? But Westlake had a hard time identifying with the spoiled wealthy Kelly, even though Kelly’s physical appearance and interests seemed to be somewhat modeled after Westlake himself. Jimmy, being younger–I’d assume some of Westlake’s own boys were around Jimmy’s age, or had been recently, or would be soon–comes off much better than Kelly. Westlake often did wonder, I think, what life might have been like for him if he’d had all the advantages growing up. Better in some ways, worse in others. There’s always a trade-off.

Oh, and one more thing–Jimmy knows what he wants to do for a living. At age twelve. Okay, in this I can not even slightly relate. But wait until you hear it–he wants to direct. As in movies. Wants to be an aw-tour. And somewhere, the God of Dortmunder’s Universe chuckles wickedly, and the net begins to close. And I say see you next week, kids. I’ll be watching you–well, those of you that post comments, anyway.

(Part of Friday’s Forgotten Books.)

I think this might have been the first Westlake book I read just as it was published, having discovered him just a couple of years previously. At that time the Westlake/Stark relationship was not really known, so I fell directly in the category of the Dortmunder readership not aware of Parker.

I loved Jimmy the Kid, and still do. I was in my young teens then, had never heard of Peugeot, and thought the plot idea of copying a crime from a book was sheer genius. I learned much later that Richard Stark was real (at least as far as a name on the spine of real books), and that allowed me to reread Jimmy the Kid with new glee.

(Something like this is nigh on impossible these days. J. K. Rowling and her pseudonym were outed in mere days).

It seems clear that Westlake must have had a blast writing this. His pride about getting details right in his novels is very clear – Murch’s comment on Child Heist is that at least the writer got the streets right, something usually not considered in fiction. Reminds me of my sister-in-law announcing that “I just have to admit that this meal I cooked is delicious.”

In retrospect, he is writing himself into a corner in this one regarding the Kelp/Dortmunder dynamic. It will continue through one more book (where it becomes strained to the point of near insipidness). This has led me to categorize the books as follows:

Hot Rock through Nobody’s Perfect are the early ones.

Why Me is the transitional one (solution worked out for the Kelp/Dortmunder dynamic, – including establishing Kelp as having the one foot in the modern technological world that Dortmunder needs whether he likes it or not)

Good Behavior through Get Real are the later ones.

In my mind, the early ones all have a similar “feel,” as do the later ones (albeit a different feel), whereas Why Me has its own unique vibe that keeps it out of either camp. There are arguments that others stand out (Drowned Hopes for the darker character primarily), but my theory works for me, and that’s good enough for me.

Well, I seem to have wandered hither and yon here. Like the proprietor of this blog maybe….

I just have to admit that I’m a corrupting influence on you. 😉

Much as the genesis of this blog is my having been able to read so much Westlake in so short a time, I do envy you being able to read some of the books as they came out, and in particular the double experience of reading this one without knowing about Parker or Stark, and then again, with the scales fallen from your eyes. That must have been sweet.

Westlake learned the hard way, in the 80’s, that it had become damned near impossible for an established author to start fresh under a new pseudonym. It’s a bit funny–he clearly wanted people to know he’d written Stark and Coe, but at the same time, there was such a sense of freedom in just being able to create a new voice, cultivate a new readership, who wouldn’t be looking for the man behind the mask. Just evaluating the work on its merits.

You have rather brilliantly summed up the tension between the early and later Dortmunders, and how Why Me serves as the transitional book. Honestly, I don’t think I could say it any better. And I don’t think I shall. You a Tom Lehrer fan, by any chance, Anthony? Westlake was–he mentions him in that very story he wrote about the origins of this novel. One song in particular.

Thanks for the research. You know, most people who come here probably don’t even read the comments section. Heh Heh. 😉

I’ve never been sure why Lehrer picked on Lobachevsky, who was a perfectly respectable mathematician. Possibly became his name scans so well. Or possibly the most famous story about him, which isn’t about plagiarism, led to thoughts of it.

Lobachevsky was working on the ancient problem of Euclid’s Fifth Postulate. Basically, to get his geometric proofs to work, Euclid had had a make an unfortunately complicated assumption about how parallel lines work. It would have been much more elegant to prove it rather than assume it, and for over a thousand years, mathematicians had been trying to do that. Lobachevsky decided to prove it by assuming the opposite and showing it leaded to a contradiction. Unfortunately, it didn’t. It led to very weird results about a geometry that was very different from the one he (and you and I) learned in high school, but it all worked as mathematics. In those days, mathematics was considered to be a description of the real world, not an exercise in abstract logic, so a geometry that didn’t seem to apply to reality was a problem, maybe even a kind of heresy.

So Lobachevsky, a bit overwhelmed, instead of publishing wrote to Karl Friedrich Gauss, the most famous mathematician in the world, saying “This is neat stuff, but I’m kind of worried about publishing, because people will think I’ve lost my mind.” And Gauss wrote back “Yeah, I discovered the same stuff a while ago, and that’s exactly why I didn’t publish.”

Anti-Euclidian geometry? Lovecraft wrote frequently of that in his Cthulhu Mythos. So really, Lobachevsky and Gauus were plagiarizing the Mad Arab, Abdul Alhazred. Or possibly Azathoth.

It’s a cool song, and I seriously suck at math, so I’ve just always assumed Lehrer had a valid point to make. But I think mainly he was paying homage to Danny Kaye, particularly the songs he sang in The Inspector General and The Court Jester. Maybe Lehrer heard a story about Lobachevsky, and maybe Lobachevsky was just making a joke, as Westlake was when he referenced the song.

Truly creative and original people are the ones who are most aware of how much they owe to others. Creativity isn’t a bunch of people ensconced in ivory towers, isolated from each other. It’s a jam session, as Westlake the jazz buff would have surely believed. You take a solo sometimes, but you’re always listening to what’s going on around you, affecting it, being affected by it. Call and response.

So maybe, instead of treating it like this isolated act, Lehrer should have written a song called The Plagiarism Mambo, but that would have sounded too much like something else he wrote.

What always strikes me as funny about this song is that the unnamed plagiarist is going to such pains to credit his primary influence.

I will have to refamiliarize myself with Tom Poisoning Pigeons in the Park Lehrer – it’s been a while.

Thanks for the support of my theory. I will await with bated breath your evaluation of Why Me – particularly regarding Chief Inspector Malogna and his secretary – among my favorite Westlake supporting cast members.

On a similar note to the above discussion, Jimmy Page once quoted Pablo Picasso noting that bad artists merely copy but great artists steal. Don’t know if Picasso was really the first to say this, but the idea’s the same. Everything is ultimately a reworking of something that came before.

I would hope Pablo (who has never been a favorite of mine, I’m more into German expressionism) was saying, like Hemingway before him, that you can steal from anyone you’re better than. You don’t copy what someone did–you take an idea and you do your own thing with it. It’s about the joy of creation, not who owns the copyright to what. And creation is inevitably a collaborative enterprise.

Now Westlake wasn’t better than O. Henry, as he’d be the first to admit, and this novel, as I said, is not quite at the same level as The Ransom of Red Chief. But Westlake was only taking one little element from O. Henry’s story–the kidnappers are at the mercy of the kid. His kid is very different, and so are his kidnappers, and the story itself has many things to say besides “Boys are a lot more trouble than you think” though it definitely is saying that. Westlake was, after all, the father of four boys.

Anyway, I think true plagiarism has to involve extremely close, specific, and unacknowledged theft, and it’s hardly likely that this book would avoid comparison with one of the most famous short stories of all time. The publisher is going to some pains to point out the familial resemblance. Still, the fact that M. Evans had the gall to say Westlake had actually outdone O. Henry shows that his reputation as a world class humorist was really starting to take hold. That’s some serious chutzpah there on that inner dust jacket–I bet Westlake winced when he read it.

Not a huge Picasso fan either, but I like the gist of the comment. As a painter (hobbyist) myself, I recall that my first efforts were always to replicate as best I could whatever my source material was. I naively considered a painting to be a “success” if it looked reasonably like the original. Now I consider a painting successful if it looks like something I made and nobody would ever be able to guess who or what I got the inspiration from. Whether I am referencing somebody I’m “better” than, or vice-versa (it’s all subjective after all), is irrelevant.

Going back to Page, the guitar riff that bookends Moby Dick on Led Zeppelin II is, among other things, a slight reworking of the lick that opens the Beatles’ “I Feel Fine.” If you know this, it’s easy to see the relationship. If you don’t, the connection is not readily apparent.

There are only so many chord arrangements in music, and there are only so many plots in fiction. Everything is an adaption of something that came before. Every once in a while two authors or musicians will independently come up with something almost the same out of coincidence. Because that can happen too.

Referencing the Comfort Station discussion, there is no reason why a reasonably competent current author could not set an entire novel in an airport, or a hotel, or whatever, and not come up with something readable, or even excellent. The Ax echoes various Hitchcock efforts. Dancing Aztecs is a riff on It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World, which itself can claim something of a tenuous tie to Don Quixote and the Canterbury Tales. Westlake even pulled off a variation on the Invisible Man concept.

One of Westlake’s gifts was that he acknowledged his source material openly and guilelessly. Art Dodge in Two Much steals a mirror trick from an old movie and cheerfully admits he is doing so. Support characters, usually Kelp or Tiny, in many a Dortmunder novel conversationally point out where Westlake is lifting a theme from Dickens, or Superman, or wherever.

All of which is to say that, no, Westlake did not plagiarize. But he reworked and adapted and aw-toured to beat the band.

Legally speaking, Westlake never plagiarized, but to write as much as he did in the crime genre–without any personal experience with crime other than stealing a microscope in college–meant borrowing heavily from earlier works in that genre, and elsewhere–books and also, very often, films. His challenge as a writer was to put his own stamp on the material he helped himself to with both hands, and he found many ways to acknowledge his debt over the years.

That being said, writers and other artists need to have the means to champion their intellectual property, or they will get ripped off, individually and collectively, over and over. Westlake didn’t think Godard had plagiarized him, but the producer who gave Godard The Jugger to adapt had not paid Westlake in full for the rights.

Now, seriously–if you’ve seen Made in USA, which I think is a terrible movie (at least judged as a story, maybe it works as an art piece, I dunno), you can barely see the resemblance between it and The Jugger, if you squint just the right way–but only if you’re looking for it.

If Godard had read The Jugger, made the same exact movie, and never told anybody about it, there wouldn’t have been any lawsuit. If Westlake had happened to see the film, he’d have probably shrugged it off–either a weird coincidence, which as you say is something that happens all the time, or else it’s another storyteller doing a riff on something he wrote. But a deal is a deal. If you promise to pay for something, you should damn well pay up. Not for nothing is this the guy who created Parker and Dortmunder.

In that piece Westlake wrote about the complex origins of Jimmy The Kid, there’s a young writer listening to his story, a prickly individual, who is just looking for an excuse to sue somebody for plagiarism, and is frustrated to learn that in some instances, Westlake is plagiarizing himself. There are writers like that, and Westlake was basically making fun of them–we all swim in the same ocean, as he said. We’re all going to tread on each other’s toes sometimes. If it’s truly egregious, then by all means call a lawyer. But don’t go looking for offense where none has been given. As others borrow from you, you shall borrow from others. Take a penny, leave a penny.

(That being said, when a bad writer borrows a good writer’s story, disguises it carefully, trots it out as his own special creation, refuses to admit he ever heard of the writer he stole from, and by some perverse quirk of fate ends up making a lot more money for his pilfered plot than the one who actually came up with it–and this happens more than you think, particularly in the entertainment biz–well, there’s rarely any legal remedy, as long as he’s not stupid enough to confess his crime. But maybe there’s a writer’s purgatory somewhere.)

Still and all, the best thing is to come up with your own idea, influenced by earlier creators, but without any true precedent, and execute it perfectly. As O. Henry did. I don’t believe anybody had written that story before. It helps, of course, to be an early pioneer, treading fresh terrain–much of Poe’s originality comes from the fact that he got to certain types of stories before most others, and even so, you can probably find other writers who got to certain things before him. Hammett didn’t invent the hard-boiled detective story–he just turned it into literature before anyone else. He gave it style.

Originality is a matter of ideas AND style. You can’t copyright style. You can’t really imitate it either, though many have tried.

And if it isn’t entirely clear, I’m agreeing with everything you said, and reworking it to beat the band. But you can’t prove that in court. 😉

I have yet to read this novel, though what I can say about kidnappings in books and films – I find the kidnap stories more dense, more emotianally complex than heist stories, just because one more human involved, and an innocent life at stake.

Not all of the kidnap stories are successful, sure, one particular movie’s stuck in my memory. It’s a noir film Big House, U.S.A., one dimensional movie, kinda uneven, with a convulted plot. It was based on a real life story, which involves a kid, this real life story is pretty great (though gritty). And the film stands the test of time just because of the original story.

http://www.dvdbeaver.com/film5/blu-ray_reviews_68/big_house_USA_blu-ray.htm

http://faustfatale.livejournal.com/269350.html

I’m not sure how many kidnapping novels there have been in the crime fiction genre. Westlake did write another one, in a much more serious vein than this, and it was never published in his lifetime. Because a movie with a distinctly satiric edge and a somewhat similar plot had come out first.

I have a copy of Lionel White’s book winging its way to me via the mail, and hopefully I’ll get it in time for it to factor into Part 2.

I’m sure I read other kidnap novels, I just don’t remember them.

I remember another good kidnap film, The Disappearance of Alice Creed, a British one this time, pretty realistic and many dimensional.

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1379177/

(Tell you a secret: a couple of years ago I began to write a screenplay for a kidnap movie. Gave up. And guess what: the plot involved a child.)

I think it’s a very tough story to get right. And it’s actually a disturbingly common crime in some parts of the world, probably much more common than bank robbery. It’s lower-risk in many respects. That’s why the legal penalty has to be so severe. Criminal and terrorist organizations use it to raise money. But the prime targets tend to be rich businessmen. That way they’re pretty damn sure to get paid off.

Probably the two most famous kidnap victims in American history are the Lindbergh baby, and Patty Hearst. The first was for money, the second for politics. The baby was killed, and Hearst was brainwashed.

And I still don’t know who the Symbionese were supposed to be, or who they needed to be liberated from.

There’s a very good child kidnapping novel called Black Alice, by Thomas M. Disch and John Sladek, both much better known as SF writers. (It’s written as by “Thom Demijohn”, because Sladek was even more famous for his puns.) It’s another book where the child is treated quite gently, and actually winds up better off than she began.

I’ve read some Disch, though it’s been a while. Sladek I don’t know. Like to read this sometime, but in the Wikipedia article for it (short, but nicely done), the genre is listed as ‘novel’. Large genre.

Another kidnap novel of note is Robert Bloch’s THE KIDNAPPER.

Thanks–going by the descriptions that’s a very dark story–which is what you’d expect from Bloch. And another in the same vein would be Patricia Highsmith’s A Dog’s Ransom.

But these are both about isolated and unbalanced individuals carrying out crude violent kidnap schemes. Not elaborately planned crimes carried out by a gang looking to get a big ransom and return the child unharmed.

Jim Thompson’s After Dark, My Sweet is about a child kidnapping committed by three people, but that’s really dark, and absolutely nothing goes off as planned. Probably the best kidnapping novel in the crime genre, but it’s Thompson, so it’s weird.

And there’s the 1956 Glenn Ford thriller Ransom!, which was remade for Mel Gibson. And the Akira Kurosawa classic, High and Low, with Toshiro Mifune as the kidnapped boy’s father–that was adapted from Ed McBain’s 87th Precinct novel, King’s Ransom. Very much from the POV of the victim’s family, and the police.

It’s not really a crime committed by smart seasoned professionals in this country (and many others)–and for good reason–the penalties tend to be really harsh. This is a crime that pushes a lot of emotional buttons. Perps have gotten the death penalty even when the kidnap victim was returned unharmed. Others have been lynched by angry mobs, and this was particularly likely to happen if a child was involved.

Makes you realize just how many taboos O. Henry was breaking with The Ransom of Red Chief. His kidnappers are warned by the not even slightly worried father of their ‘victim’ that the neighbors are so delighted the boy is gone, they might lynch anyone they saw bringing him back. That’s how good O. Henry was at what he did. The same people who might have done the lynching were reading this story and laughing their asses off. When you’re that funny, you can get away with almost anything.

So anyway, what I’m really wondering here is how many novels in the crime genre were written pretty much exclusively from the POV of a gang of kidnappers, and whether they ever got away with it. That’s why I want to read Lionel White’s book. And hopefully I will have done by next week.

I too came to Jimmy the Kid before I encountered Parker (but not long before) and for what felt like a long time, I actually thought Child Heist was an actual Parker floating out there. As I made my way through the Parkers, I kept waiting to get to Child Heist. I can’t remember when or how I figured it out, but it was something of a relief. You’re right. Parker’s no kidnapper.

I appreciate everyone’s tact and good taste in not mentioning the Gary Coleman-starring adaptation of Jimmy the Kid, but the completionist in me can’t let it go unmentioned. There, now that that’s out of the way, let’s move on.

And I want to point out that with equal disgression, I failed to mention the 1999 German adaptation, directed by someone named “Wolfgang Dickmann.” I mean, seriously. That’s some world-class restraint I was showing there, people.

Dortmunder’s no kidnapper either, but that’s the joke–Parker, as we know, won’t sanction jokes–at least not when they’re on him.

Literary plagiarism laws only apply to fictional events and persons.

There’s a book called Holy Blood, Holy Grail that purports to be the history of the descendants of Jesus and Mary Magdalene, who moved to France and eventually became the Merovingians ruling house there. If this story sounds familiar, it’s probably because Dan Brown appropriated it for The DaVinci Code. When HBHG’s authors sued Dan Brown for copyright infringement, they lost, because there’s no such things as plagiarism of historical facts, even ones that were completely made up.

Dan Brown should have been sued for impersonating an author. And those HBHG writers should have been sued for impersonating historians. But it’s an interesting point of law–if they had confessed to making it all up, could they have won their case?

Jimmy The Kid – my thoughts

As it’s generally regarded as significant, if I’m going to review Jimmy, I should first assign myself to a group. Would it be the group that didn’t know about Stark’s Parker or the one that did? In my case not quite either. I knew about Parker as Richard Stark’s ‘Violent Arm’ but I chose not explore further as I prefer soft-boiled fiction. Dortmunder is perfect.

I’ve been catching up on the early John D’s so I think I have a fresh eye for the differences in style between the first three (1970-1974) to the six or so from the noughties. For a start I think they’re shorter, and Jimmy the shortest of the three, and it certainly seems a simpler linear story with no subplots.

This is just one opinion but I feel Donald Westlake seems to have an early fix on his characters but he has not settled on the crucial relationship between Dortmunder and Kelp. The way it read in Jimmy it seems John and Andy were heading for a divorce. It even made me uncomfortable and you couldn’t mine the relationship for comedy.

I need to state a bias which will have affected my judgement on Jimmy The Kid, which I’ve just read. I’m editing and revising a novel of my own which contains an inept kidnapping as part of a crime caper so it’s of particular interest to see how the Harrington kidnapping goes wrong. We know that John is a planning genius so why wouldn’t he shoot holes in Kelp’s simplistic plan which starts to go wrong within minutes? Every project manager needs to be a Jonah or a Devil’s Advocate if he’s going to be successful. And as John usually is. So I reckon DEW got away with one here. If the cops were anything less than half stupid they would have caught the gang by day 3 and turned Jimmy into a short story!

[Spoiler] If you think this is too critical, let me say that Jimmy is worth reading for some brilliant twists at the end, from John being knocked out by the suitcase with the money, complicity between kidnappers and victim, their separation of the beeper from the suitcase and the business at the end about Richard Stark wanting to sue them for stealing his idea. Brilliant. Reread every five years or so, doctor’s orders.

By the way, if you’re interested, the books I’ve just bought were new copies printed in 2011 by Mysterious Press at $10 or so.

Russell

In the early novels, the Dortmunder/Kelp dynamic is very different–Dortmunder always ends by vowing never to listen to one of Kelp’s crazy schemes again, and then in the next novel, he gets pulled back in. This basically continued through Why Me? The ending of that book convinced Dortmunder that however much he might deplore Andy’s weird devotion to him, he couldn’t disown it.

After that, it was more of an equal relationship, more or less amiable (frequently less) and Kelp became much less of a nebbish–at times surpassing Dortmunder for criminal cunning, although he has to admit at one point that the one thing he can’t do is come up with a plan. He has ideas, but a plan is a bunch of ideas stitched together, and he can’t do that. His mind doesn’t work that way. Which explains, you might argue, his clinging to Dortmunder the way he does–each supplies a lack in the other, but Dortmunder never does quite see it that way.

On the whole, I think the earlier relationship was funnier, and I prefer it, but see why it couldn’t go on forever–it got too hard to explain why Dortmunder kept working with Kelp, and of course he had to.

Nitpicks often miss the point of a story–which is not to be documentary realism, but to get an idea across (or a bunch of them stitched together). Dortmunder is a genius planner, but he’s also a Jonah, cursed by ill-fortune, and quite capable of making mistakes, as he does throughout the series. He knows this is going to go wrong, but he has to work, and it’s hard for him to find unguarded cash to steal in a world of electronic cash. So he goes along with it–fatalistically, pessimistically, but he goes.

Probably he doesn’t shoot holes in the caper (which you should please remember was devised by “Richard Stark,” not Andy Kelp) because it’s tightly plotted–on paper. It’s actually very hard to find holes in a Stark caper. But the point is that Real Life can and does shoot holes in every scheme, and not just the criminal type.

The problem is that it’s fiction–and yes, Dortmunder is a fiction as well, but a different kind. In Parker’s reality, things often go wrong (in every single book, actually), but never the same things as in Dortmunder’s reality. Dortmunder needed to adjust for that, but he doesn’t know how–he just lets himself get swept up in Kelp’s enthusiasm, and you can hardly quibble with that, since it’s one of the premises of the series.

As I remarked, it’s really about the odd relationship between crime fiction and criminals. Or really, about fiction relating to any profession, and the professionals who read it, and make the characters into role models–and then writers model fictions after them–and repeat. Interactive. So if we do what you suggest–that’s gone. In any event, Dortmunder would never want to kidnap a child. It would never occur to him (It would never occur to the real Parker either, but I explained where the idea for this came from, right?)

I don’t ask my fiction to be realistic–If I want reality, I have all I can handle, all around me–all I ask is to make me believe it while I’m reading/watching it.

I mean, does Candide make any sense at all? Does Gulliver’s Travels? Does Don Quixote? Why does it take so long for the authorities to stop a crazy old man going around with a sword and lance, attacking people at random? You know why? People liked the first book so much, Cervantes had to write a sequel, and the good Don was treated a lot more sympathetically the second time around. That was also about the weird relationship between popular fiction and reality. Not a new idea.

As to the cops–c’mon. Let’s not take all the fictions about them too literally either. They are hardly geniuses (some are solid pros–not nearly enough). They often fail to catch far less competent felons than the Dortmunder Gang, or catch them long after the fact–or finger innocent people. They do things on a routine basis that make no sense on any level–you read stories about police in the papers, you think this is the worst-written story ever–but it’s all true. Unfortunately.

Hope the book works out, but nobody but Westlake ever wrote as good a kidnapping story as this, unless it’s O. Henry, and that was just a short story.

Yes, the running gag particulars of the Kelp-Dortmunder relationship that were hilarious in the Hot Rock, and still funny as hell in Bank Shot, begin to show signs of age in Jimmy the Kid. Your comment that the characters seem veering towards divorce is spot on. In Nobody’s Perfect, one of the least successful of the series (at least the third act), it did what used to be called jumping the shark.

In Why me, which as I recall came after a longer break than typified the first four, a solution is found. I don’t know if Kelp’s fondness for technology which first appeared in that book was intended by Westlake as the path forward or as just the gag du jour, but it worked to allow the relationship to develop. Dortmunder hates technology, but cannot live, and certainly cannot steal, in a technological world. This all transpired around the time of the societal joke about parents and grandparents needing a 12-year old to program their VCR. Kelp served in Why Me as Dortmunder’s 12-year old savior, and somehow over time that has served to guide the uneasy peace between the two. Of course, there is more to it than this. Kelp became considerably more competent over time, albeit remaining subject to the twisted whims of his creator. Dortmunder was given an ever wider gang of cohorts, many of whom made Kelp appear almost human in comparison. But that bridge to a digital real world that Dortmunder dug his heels in against became very much the glue.

Perhaps the Westlake who clung to his manual typewriter until death is where Dortmunder emerged, and the Westake who used a computer and fax machines and whatnot for the necessities of communicating with publishers etc. gave birth to latter day Kelp…

I’d say the problems really began with Nobody’s Perfect. The Dortmunder/Kelp dynamic was never funnier than it is here, and their differing relationships with reality never more acutely addressed. Kelp is the hero of his own story, always. Dortmunder doesn’t see himself as being a character in a story, anymore than Parker does (Parker’s Kelp is Grofield, believe it or not). That he is one anyway is something he’s determined to ignore–which tends to make for better stories, oddly enough. (“Though she feels like she’s in a play–she is anyway.”)

But yes, you’ve hit on the solution–Kelp’s obsession with the new, contrasted with Dortmunder’s adherence to the tried and true. It works both in the pragmatic sense–Dortmunder needs somebody to keep his tradecraft up to date, since the world won’t stop changing, no matter how many times he begs–but also in the satiric sense–change is not always good. To say the very least.

Kelp is a needed irritant for Dortmunder, but in Why Me? Dortmunder is forced to recognize that necessity–grudgingly. But again, he also has to acknowledge the value of Kelp’s friendship–in a way Parker was never forced to acknowledge Handy McKay’s. (Grofield never really showed any deep loyalty to Parker–they were at one on the issue of professional courtesies only lasting as long as the job did).

Stark can’t let Parker show that kind of emotion–and Westlake has to be careful not to ever let Dortmunder get all hearts and flowers–but he can let some of his own gratitude towards his real-life friends bleed through there, in that alter-ego he knew full well more faithfully resembled his creator.

(Though I can’t imagine Dortmunder ever using even a manual typewriter.)

I should say here that I have a particular fondness for Nobody’s Perfect, despite the weak ending. I think maybe it’s that I sort of think of it as a Christmas book: that terrific Christmas party scene that has Dortmunder saying ‘God help us, every one.’ Charming lines like: ‘A Christmas present isn’t something you steal. A Christmas present is something you buy.” The names of the parts: The First Chorus, The Second Chorus and so on, that sound almost like the book is punctuated by carols.

Then there’s the Porculey stuff, which is so good. My local shopping mall closed down, as seems to be happening to malls all over this country, but I keep wondering if I could come up with a scheme where I could move in with a leggy blonde and pay whoever the rent. I have no artistic talent whatsoever, but I may be writing a novel soon. I’m getting all dreamy now that I’m musing about it…

This comment should probably be in the Nobody’s Perfect post, but what the hell.

I don’t see how anyone couldn’t be fond of each and every last one of them, but fondness shouldn’t preclude criticism. Basically the last third of the book is ill-conceived (however fascinating, since it’s Mr. Westlake’s only attempt at setting any book of his in London, which apparently looks like Queens, then Scotland, where policemen apparently say “What’s all this then?”)

It almost feels as if he had two different story ideas, neither was sufficient for a novel, and he figured out a way to splice them together. And the joins show.

The Porculey section I much admired, but of course shopping malls were considerably more familiar territory for Westlake, and I still say Porculey is modeled after Robert E. McGinnis).

And indeed, what the hell–nobody’s perfect.

I defer to your wide range of approach, Fred. Several of us perhaps would choose Westlake as a special subject and you would come top.

I think the explanation for why I would disagree with you about the early relationship of John and Andy is a gravitational tug. I’ve immersed myself in most of the 21st C titles and formed my impression of the relationship. Then we go back in time (author time not character time) and find that although Dortmunder is still 38, he’s behaving like someone much younger and you feel like telling him to grow up. At least to criticise fairly. If I’d been reading from the beginning no doubt it would be different.

Yes of course the caper was devised by Richard Stark but Dortmunder’s attitude is bolshy here. He makes a point of standing back from the blueprint rather than (as a planner) being rigorous in testing the potential weaknesses. But of course it makes a good story.

“As to the cops–c’mon.” One interesting aspect here is that the technical range of expertise has so vastly expanded that we have to remind ourselves we were still years from mobile telephony, DNA and Google searching which inform police activity now. Of course the cops are always suckers for a take down.

Yes, I’m reluctant to allow characters to reassign themselves, although of course they’re free to become much more tech savvy as Kelp is and in my view makes him a worthy co-star. Interesting comments, Anthony, about the manual typewriter which I didn’t know. And we used to love ‘em.

Talking again about character-change, (as I’m halfway through Nobody’s Perfect for the first time) I found Tiny a bit of a stomach curdle in NP. He’s a bit more civilised later on, fortunately. As I mentioned earlier, I like my fiction soft-boiled.

I haven’t met Porculey, yet. Lovely name!

Unlike the Parkers, where I began with some of the last novels, then went back to the beginning (and ended up preferring the earlier books), I read the Dortmunders in precise order of publication.

But I doubt my reaction would have been much different if I’d read them out of order. Some of the books are much better than others–I found much to love in the late Dortmunders, but they are showing signs of wear. The first three brim with creative vitality. They are the crown jewels of the series. Then there’s the middle age of Dortmunder (appropriately embodied by the medievally themed Good Behavior). Westlake stretching out, finding new wrinkles, deepening the group interaction.

By the time you get to the 21st, it’s all very meta (embodied by the finale, Get Real), and I can appreciate that, but without the earlier books to provide a foundation, they’d be pretty weak tea. Still, a series has to be appreciated in its entirety–and without the earlier books, there’d be no later ones. Also, I could so easily pick the books you’re approving to pieces, if I liked. It’s only when we’re not really into a book that we start seeing all the plot holes. You’re making allowances for the later ones because that’s where you fell in love. They have all the same problems you describe in Jimmy the Kid–only more so, because they’re longer. The truth is, if Westlake had ended the series with Jimmy the Kid, it would still be a great series, and we’d still remember it. It might actually be more respected, over-familiarity breeding contempt and all–but I wouldn’t want to give one of them up. Not even Nobody’s Perfect.

It’s a common feature with series fiction–after time, the author will begin to tire of a concept, but his readers don’t (think of Conan Doyle trying–and failing–to kill Sherlock Holmes). We just keep wanting more of the same (only we want the characters to develop–how does that work?) Westlake couldn’t write the same book over and over. He had to keep changing up. He might revisit earlier themes, try to make a story that didn’t work in a previous effort come together, but it would never be the same thing twice.

And if we continue this exchange, we’ll be the ones fruitlessly repeating ourselves, so let’s leave it be for now.