As I said, in some subterranean way Parker had come out of or been formed by that experiment in unstated emotion in “361”, and his habit of doing rather than reacting has made him for me the ideal series character; since he won’t tell me what he really wants, he can never use himself up by becoming completely satisfied.

I don’t mean to be hyperbolic when I suggest my own creation is in some ways still mysterious to me. I record his doings, and I know when what I put down is right, but I can’t always explain it, least of all to myself. Why does Parker wait in dark rooms? Why is he so totally loyal without ever showing comradeliness? What is the money for?

Going back to Buck Moon’s suggestion, I did hesitate for some time, unsure what might lay further down that road. I was very aware of the dangers inherent in sequels; any number of writers have returned to a well only to find it poisoned. (A sequel to The Desperado, that early Gold Medal Western, was written and was so bad it almost destroyed the original.) Nevertheless, finally, because of Parker, and also because of the money (a motivation Parker would understand), and also because of the implicit test of my skills (another nod from Parker), I told Buck Moon I’d give it a shot.

The change in The Hunter was so easy, so easy. It became at once evident that my earlier ending had been false, that Parker wouldn’t have permitted himself such a sleazy finish. When I let him have his way with those cops, he was even quicker and less emotional than usual; because I was watching, I suppose, and life was starting. The look he gave me over his shoulder as he went through the revolving door contained no gratitude, but on the other hand it didn’t contain scorn either. He isn’t a wiseguy.

A few years after his birth, I discussed Parker with a movie director for a (finally aborted) planned film from one of the books, and this director claimed that Parker was really French, since the difference between fictional French robbers and fictional American robbers is that the French steal because that’s what they do, while the Americans steal to get money for their crippled niece’s operation. English-language villains (other than Iago) have to be explained, while French-language villains are existential.

It was an interesting distinction he’d found there, but I thought it at the time too narrow, and I still do, since in every other respect Parker is as American as Dillinger. In fact, I think he may have appeared now and again in the past, in war stories and police stories and even Westerns, the silent, morally neutral fellow barely visible in a dark corner of the setting, who suddenly and inexplicably helps the hero out of a tight spot, than laconically fades into the shadows again, with no explanation asked or given. That was romantic bunkum, of course; it would take more than a hero in trouble to make him really take a hand. But the writers were aware of him back there, and wanted to use him somehow. So did I, but without embarrassing either of us.

Donald E. Westlake, from (again) the Introduction to the Gregg Press edition of The Hunter

Jupiter commanded all the birds to appear before him, so that he might choose the most beautiful to be their king. The ugly jackdaw, collecting all the fine feathers which had fallen from the other birds, attached them to his own body and appeared at the examination, looking very gay.

The other birds, recognizing their own borrowed plumage, indignantly protested, and began to strip him.

“Hold!” said Jupiter; “this self-made bird has more sense than any of you. He shall be your king.”

Ambrose Bierce (plagiarizing Aesop)

What is originality? What does it mean to be original? The question itself is deeply derivative, but worth asking again in this context, I think. When it comes to art, does it mean to do something first, or to do it so well, so memorably, so influentially, that all those who follow in your wake owe something to you? Many later works trace their origins to what you did. But didn’t that ‘original’ piece of work in fact find its own origin in many earlier ones, and they in turn to still earlier works, going all the way back before the dawn of history, to artists whose names no one will ever know?

Most people who care, Donald Westlake most definitely included, would say the most original writer in American crime fiction was Dashiell Hammett, but he did not, in fact, originate hardboiled detective fiction, cynical worldly-wise two-fisted private dicks navigating the seamy underside of industrial-era America, or really any of the now-familiar tropes of that genre. What made him original? His style. His eye for character, for story, for the telling little detail. Not what he did, nearly so much as the way he did it.

His authenticity as well–his firsthand knowledge of the terrain–but the problem with that was that his success as a writer took him further and further away from the life he’d drawn upon for that authenticity, and when he ran out of experiences to draw upon, he didn’t know where else he could draw from. He stopped writing, and continued drinking. But he’d started something that could survive–and thrive–without him. And still does, after a fashion.

Well, that’s mere genre, of course. Nobody expects originality in Genre-ville (and yet it shows up there with perverse regularity, for all that). When we talk about originality in literature–when we talk about Literature with the upper case ‘L’–don’t we really mean somebody like Vladimir Nabokov? A writer Westlake oddly compared to Hammett once, said they both had a knack for writing characters who could show us their emotions indirectly, without speaking them out loud. But Hammett was just cranking out entertaining nonsense for the pulps. Nabokov was crafting revolutionary innovative stories nobody had ever told before. Like Lolita. A book without any direct antecedent. Except for a book with exactly the same title and premise published forty years earlier.

And this should serve as a lesson to all of us who say this or that writer was the first to do such and such. How do we know? How could we ever know? So many novels and stories and plays and films and radio shows, and television shows and comic books and my head spins around in circles just thinking about it.

Even something as seemingly simple as divining what influences went into producing a hardboiled crime paperback in the early 60’s can turn into a maze of obscure references and cross-references. The more we read, the more we know–and the more we know that we know nothing. Because we realize how selective our memory of literature really is, how many innovative fascinating works have been stuffed into our pop cultural attic and forgotten by all but a handful of cognoscenti–I daresay even Patti Abbott doesn’t know how many.

All of which makes it even more remarkable when a book that by all rights should have been relegated to that attic, isn’t. The Hunter is by no means the most famous or well-regarded book published in 1962, or anywhere near it, but it’s the only hardboiled crime novel that appears on this list. It’s also one of the very few mystery novels on it. And perhaps more importantly, it’s currently at #42 on this list. Critical respect is nice and all, but not as nice as being read from generation to generation. Because, as Westlake liked to say, the difference between being in and out of print is the same as being alive or dead. The Parker novels are very much alive, and look to stay that way.

And sure, that’s partly down to famous film adaptations, Darwyn Cooke’s graphic novels, a certain website I might name, and Levi Stahl’s one man crusade to get those novels back into bookstores (and assorted digital devices). But all of that derives from the enduring fascination inspired by the books themselves, and all of them spring from this book, the start of a saga that spanned twenty-four novels written over the course of maybe forty-six years, depending on when Dirty Money was finished.

So if a book is that important, maybe we could devote a little time and thought to figuring out where the hell it came from. Because books don’t just write themselves. Not even paperbacks with deliciously lurid covers. Worth a try, no?

Last time, I touched on some plot elements in The Hunter that seem to have been inspired by Graham Greene and Raymond Chandler. But the real key to the longterm success of the Parker novels is Parker himself. Where did he come from? From a lot of places. There had never been a character like him before–but at the same time, Westlake suggested, he’d always been there, though not usually as a protagonist. Storytellers sensed the potential of a morally neutral character who is somehow still admirable, even heroic, in ways that are hard to explain. But they were held back by the conventions of whatever form they were working in (and all forms have their conventions).

Westlake himself was going to kill Parker off, then an editor at a publisher said “If you bring him back for a few books a year, we’ll buy the first book.” And as he said in the quote up top, he quickly realized the story worked better that way. Not really believing in what he was doing, he’d written an arbitrary “Bad guys always get their just deserts in the end” finish to a story it just didn’t belong in, because its hero didn’t live in a world of good and bad, right and wrong. He was outside of all that. He was something else.

And the fact that Gold Medal published The Name of the Game is Death that same year–with its unapologetic thief, murderer (and rapist) still alive, if somewhat worse for wear, vowing he’ll be back–shows that publishers in this declining niche were willing to experiment a bit. That character’s moral ambiguity didn’t hold up long, though–because Dan J. Marlowe simply wasn’t as good and honest a writer as Donald E. Westlake (and maybe because that book actually wasn’t a big seller for Gold Medal). He turned his bank robber into a government agent by the third book, an organization man–that ruined him. The problems were already there in the second book, though. Marlowe didn’t know what he had, didn’t know how to build on it. Sequels are tough to write for characters like this. Westlake knew that.

We’ll talk more about Mr. Marlowe in future, but leaving him aside, as I mentioned already, Patricia Highsmith had beaten both him and Westlake to the punch with Ripley, in 1955. Except she had not known what to do with Ripley after letting him walk away from cold-blooded murder with a nice income left to him by his victim. Unlike Parker, he would kill people who were not really guilty of anything except bad life choices. Ripley wouldn’t return until 1970, and would only be in five books over the course of 36 years. He personally murdered a total of ten people. His only real goal was to be independently wealthy, and live in his nice villa with his rich beautiful French wife. And to not be bored.

Highsmith liked writing about him, the books sold well, but there just wasn’t all that much she could do with him–he wasn’t a character you could write lots and lots of books about. He got used up too easily, once you solved his problems. The last book quite intentionally did just that, and she was done–a few years before her death in 1995.

Westlake, having taken a long break from Parker starting in the mid-70’s, came back to him in the 90’s, and was writing Parker books up until very shortly before his sudden death from heart failure. The last book was published the year he died. He self-evidently was laying the groundwork in that last book for more books he didn’t know if he’d get to write or not. Parker couldn’t be used up, so he doesn’t have an ending. Moral or otherwise. But he had a beginning–many of them–false starts, I’d call them. Three in particular.

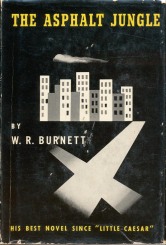

W.R. Burnett‘s The Asphalt Jungle, probably the first modern heist novel (depends on how you define it), is not that much read today. Burnett isn’t that much read today, you get right down to it. His deep influence on crime fiction came about in an odd and lucrative way–by having Hollywood grab his books when the ink was scarcely dry, and make truly great movies out of them, that overshadowed the original works, made them almost irrelevant footnotes to themselves. (Would I have read the book at hand if it weren’t for John Huston’s movie? Nope.).

He seems to have liked Hollywood, met his second wife Whitney there (an ambitious and very attractive studio secretary), and I don’t know exactly how he felt about the creative compromises he’d made. But I do know that without him, we wouldn’t be talking about Parker novels, because there’d be none to talk about. Here’s a picture of himself and the missus, from the back dust jacket of my personal copy of The Asphalt Jungle.

I guess her horse is just out of frame. It’s really hard to read that book, look at that photo, and not make certain connections to the story (if you’ve seen the film, you know the story), written a few years after he married the second Mrs. Burnett, who I rather suspect he left the first Mrs. Burnett for, but I don’t know offhand. Looks expensive, doesn’t she? But this book is dedicated to her, and I get the impression she was a driving force in his career, much more than just a trophy. There was no third Mrs. Burnett. Anyway, that’s not our main point of interest here.

The book opens with a quote from William James–“Man, biologically speaking…is the most formidable of all beasts of prey, and, indeed, the only one that preys systematically on its own species.” Hmmmmmmm……..

I shouldn’t need to summarize the plot–Huston was maybe the best and most faithful adapter of crime novels in the history of film. But never slavishly faithful. The novel has a lot of extraneous details that Huston necessarily cut out, and makes a few significant changes (to the ending in particular), all of which improve the story. The book reads at points almost like a treatment for a movie. Burnett knew by this point who his real audience was–the studios.

But that doesn’t mean he didn’t have things of his own to say. His prose is plodding but effective. His characters maybe a bit two-dimensional at times–stock types, to be eventually played by stock players, but vivid and believable for all that. His plotting is solid and sure. And he’s got a vision, a theme, of outsiders struggling against the system, and against themselves. He’s not a great writer, even by pulp standards (the pulp standard being Hammett), but he’s maybe half of the way there. Sometimes more than half.

A tall rawboned, dark-faced man of indeterminate age was standing in the doorway, looking down at him with mild surprise. Riemenschneider felt a sudden prickliness in his scalp and an unpleasant coldness in his hands as the tall man probed him with his dark eyes. “A bad one,” said the little doctor to himself, as he looked up blankly.

Dix Handley. You hear that name and you see Sterling Hayden in your mind’s eye, and that really was Hollywood casting at its best–but that’s not quite the image that comes to you when you read the book. Still, the movie captures everything essential to the character, his laconic toughness, his odd criminal sense of honor, his implacable need to mete out retribution to anyone who insults or crosses him. But he’s not a thinker, a planner. He’s all action, instinct, no brains. He’s only good in the moment. But he’s damned good in the moment.

Then there’s Riemenschneider, the little German heist planner (one of a number of roles Sam Jaffe was born to play). A genius at what he does, almost more in love with getting the money than spending it (mainly on women). His weakness is that he can’t resist a pretty young face, even when he’s on the run–and of course he’s no good at violence, it rather disgusts him (though he’s not a man you want to cross either).

He’s increasingly impressed by Dix, sees some mysterious power in him he can only vaguely recognize and understand. He begins to see Dix as almost a missing half that would complete him–Blaster to his Master, you might say (Fafhrd to his Gray Mouser?). He suggests they become partners, escape to Mexico together, but Dix isn’t interested. Westlake was interested, though. Don’t even try to tell me he wasn’t.

Dix’s main weakness, aside from his lack of planning ability, is that he thinks that down inside he’s still the horse farmer he was raised to be down south, still a Jamieson, still remembering the life that was taken away from him, still dreaming of getting it back, buying the land they lost, raising horses. It’s not who he is anymore, but he can’t bring himself to see that. The old country boy in him is stronger than the beast of prey. He’s best when he’s living in the present, but he’s usually mired in the past. That’s his tragedy, and tragic characters always come equipped with tragic endings.

(Did I mention Dix has huge knobby-knuckled hands? No? Remiss of me.)

Anyway, this is the book that really started the specific sub-genre Parker lives in (there may be earlier examples, but between the book and the film, this would still be the real starting point). The loot is in a tough spot to get at, but there’s a plan that could work. You have to finance the job, which means dealing with suits. You have to gather together a talented string of professionals, each of whom comes with a certain amount of unavoidable baggage–there are weak links, unanticipated wrinkles. Nothing ever succeeds as planned. The robbers are caught and/or killed. So that the honest people reading about them can enjoy the thrill of plotting and executing a heist without sharing in the guilt–so they can tell themselves “We’re still good people, after all.”

Well, maybe that last part isn’t 100% necessary? Who do we like in this story? The cops? Not even a little bit. They’re just the Hayes Office censors with badges and guns. The only people you ever love in a Burnett crime novel are crooks. You root for them, and then you grieve for them. But sometimes, in Burnett, that veers over into cheap sentimentality. That we could do without. That’s maybe what stops him from getting all the way to being a great writer. But he got close a few times. And he got rich. And he got the second Mrs. Burnett. There were compensations.

(Obviously I’m not qualified to judge him as a writer on the basis of one book–those who have read more of him sometimes paint a more glowing portrait. But still have to concede his reputation today stems mainly from the movies.)

Anyway, compensations aside, there were imitators. Lots of them. That’s how genres begin. The book was published in 1949, and the movie released in 1950 (meaning MGM had probably gone into pre-production before the book was even printed). It was a critical success, but a box office dud. A bit ahead of the curve. As truly influential works often tend to be. Other aspiring storytellers read that book, saw that movie, recognized the potential. One of them was David Goodis.

The heist story was never his main thing. ‘The Poet of the Losers’ was more about people who had hit rock bottom in life finding themselves in some kind of trouble, looking for an escape hatch, not always finding it. He came at this story from a variety of angles, drawn mainly from crime fiction, but not invariably.

The way Black Friday came about was that Goodis had submitted a novel to Arnold Hano at Lion Books–The Blonde on the Street Corner. It’s a book about a poor Philadelphia kid in the Depression who can’t get work, and he lives with his parents, hangs out with his loser friends, and they dream about making it big, and there’s this nice girl he loves but he can’t afford to marry her, so he decides to settle for easy sex with a married woman. That’s how it ends. That’s the entire story. It’s not noir, it’s not crime fiction, there are no actual crimes committed other than adultery, and I believe there’s exactly one fist fight, because there has to be a fist fight in a Goodis novel.

Hano reluctantly published it–Goodis was a name, and Lion Books was the bottom of the barrel. Goodis kind of enjoyed the bottom of the barrel (it’s a Goodis thing), and probably figured if he wanted to keep getting published there, he better write a book with some crime in it. Black Friday was it. Hano thought there could have been a bit more action, but overall, he was fairly satisfied.

Black Friday starts with a young man of limited funds and no shelter facing a Philadelphia winter without an overcoat. So he steals one. The cops are after him, and not just for the overcoat; there’s a backstory (always a backstory). Through an unlikely sequence of events (though not for a Goodis protagonist), he ends up joining a gang of burglars who specialize in robbing rich houses on the Main Line. Because hey, why not?

The protagonist in this book, named Hart, is not our primary concern. For my money, the most interesting character is the leader of the string, a thin silver-haired man whose name is Charley. He doesn’t need a last name. What he really needs is to be played by John Slattery if they ever make another movie of this book (though Robert Ryan, in the 1972 French version I haven’t seen yet, might be even better).

The man with silver hair was saying, “You’re too much trouble.”

Hart said, “I don’t know about you, but I don’t like to be choked.”

“Do you think I like to shoot people?”

“No,” Hart said, “You’re a nice guy. You’re a swell guy. You wouldn’t shoot anybody.”

“Unless I had a reason.”

“And would it have to be a good reason?”

“Sure,” said the man with the silver hair. “I don’t like to shoot people. I don’t get any special kick out of it.”

Charley, unlike Dix, is the heist planner–the brains of the outfit. Surrounded by temperamental idiots who complicate his work. He’s constantly being forced to decide who lives or dies. He’s also suffering from impotence, a problem he can only temporarily solve by getting really drunk every few months. And he is suffering–he does not see this as a normal loss of interest that can be fixed by pulling a job. But Charley’s not the type to whine about a bad break–what can’t be cured must be endured, as the saying goes. (Pfizer begs to differ.)

His amply proportioned lady love (big lusty women are another Goodis leitmotif, and not just in his fiction) is having a hard time dealing with the abstinence thing, and even though she truly loves Charley, she turns to the young protagonist to solve her problem, and even though he’s falling for a girl his age who lives at the hideout (it won’t end well, because Goodis), he’s in no position to say no, because this older woman knows he’s not really a crook. The big crime the law wants him for was not committed for money. He’s an amateur.

Charley doesn’t like it, the two of them knocking boots, but he doesn’t kill over sex. He kills over unprofessional behavior. If he found out Hart wasn’t really on the bend, he’d whack him on general principle. Nothing personal. People should do their jobs. His job is to steal. He only trusts people who see that as their job too. He’s got some pretty dangerous guys in this gang of his. They’re all scared to death of him. One of them has a beef with Hart. Charley could care less about his beef. They have a chat.

“Look Charley, I don’t like that guy.”

“And I don’t like you,” Charley said. “But I put up with you because you know your work. I like the way you work, but there’s got to be satisfaction on both sides. Do you like the pay?”

“Look, Charley–”

“Do you like the pay?”

“I like the pay.”

“All right, then, you do as you’re told. And don’t do things I don’t want you to do.”

There’s this weariness in his voice you can hear in every word he utters. He knows he’s the only real professional in the bunch. He knows they’re going to keep doing stupid things, and he’s going to have to clean up the mess. But this is what he does, and these are the people he needs to do it with.

So he’s got these rules, this code he lives by, and you think you know what he’s going to do, but then he surprises you. There’s a guy a bit like him in Goodis’ earlier book, Nightfall, but he’s much better developed here. On the one hand, he’s got no conscience, no qualms about killing people who complicate his work in some way, professionals or civilians. But on the other hand, there seems to be more to him than that. He’s not so easy to sum up, Charley. I won’t even try. Read the book.

Westlake read the book–he mentions Goodis specifically in that intro to the Gregg Press reprint of The Hunter I keep bringing up. He was reading the Gold Medal crime novels incessantly, probably even before he was a professional writer. This particular book isn’t a Gold Medal, but he would have been reading Lion Books originals as well, particularly if he already knew the author from Gold Medal.

I was the right age at the right time to be very heavily influenced by the arrival of Gold Medal books. These were in the fictional form known as the novel; but not really–or so it seemed at first. They were stripped down and lumpy and crude, like a beach buggy. Half the time they seemed little more than 50,000-word short stories; all that build-up, all those characters, all that preparation of setting and emotions and scenes and relationships, just to end in a shootout in a swamp. These yellow-spined paperbacks had compulsive strength, but without beauty, like acid rock: but they were interesting.

And either the books got better or my critical sense got worse. In any event, I began gradually to make sense among the by-lines in this new garden, and to realize that here too there were gradations from very good to very very very very bad. Once I’d separated the writers from the bricklayers, everything was fine.

Gold Medal introduced me to John D. MacDonald, Vin Packer, Chester Himes, David Goodis and, by far the most important, Peter Rabe. (Rabe’s Kill the Boss Goodbye [1956] is one of the best books, with one of the worst titles, I’ve ever read.) The understatement of violence, resulting from Rabe’s modesty of character rather than modesty of experience (which is why Hammett had it down pat and Chandler could never quite make it work), was refined in these books to a laconic hipness I could only admire from afar.

See what he does there? He puts the emphasis on Rabe. Yes, Rabe was a huge influence on Westlake, and Westlake went out of his way to see that he was rediscovered. But I’ve read most of Rabe now, and I can’t point to a single moment in any of those books that seems like a specific influence on the book Westlake was introducing (in fact, I can’t think of a single moment in any Rabe book that reminds me that much of any moment in any Westlake novel).

And yet, he goes out of his way to mention writers who did very directly influence this book, or so I think. Like I said in the comments section last time, he points one way, while his eyes go another. He’s playing fair. He’s giving us the clues, but we’ll have to work for it.

So maybe he got the idea of Parker’s bizarre sexual cycle from Charley–maybe not. Maybe something of Charley’s obsessive monomaniacal professionalism went into Parker. Maybe not. And maybe a story Goodis wrote called Black Pudding was a second influence (along with A Gun For Sale) on the main revenge story of The Hunter. Actually, I don’t think there’s any maybe about that.

Black Pudding is about an armed robber named Kenneth whose partner has a thing for his gorgeous blonde wife, so while they’re on a job, he knocks Kenneth out with a pistol butt, and leaves him for the cops. He’s doing five to twenty at San Quentin when he gets the divorce papers from his wife Hilda, who has left him for the partner. He goes crazy for a while. After nine years, he gets out, and does he seek revenge? Nope, he decides to go back home to Philly, and put it all behind him. But the partner is worried he’ll have second thoughts, so he sends some killers after him to make sure. Kenneth’s running for his life in Philadelphia, and man that’s a tough town if you’re a Goodis character.

So hiding from the killers, he meets this horribly scarred young woman named Tillie (not just emotionally scarred, but that too). She also had spousal problems. So they start liking each other, but she convinces him he needs to get revenge–she felt better after the husband who cut her face and made her an opium addict killed himself. Revenge is like black pudding, she says. Kenneth needs to get a taste of it if they’re going to have a future together. He can’t hide from his anger. Anyway, if he doesn’t finish them, they’ll finish him. She wants to help, but he wants her out of it.

So it all works out (unusually, for a Goodis story). He gets his revenge without bloodying his hands (well, not too much), and he heads back to Tillie, with the emotional closure he needed to start over fresh. And they all lived happily ever after (after Tillie gets plastic surgery, that is).

It’s a good yarn (Goodis, like Westlake, wrote a huge number of short stories for magazines, but didn’t typically excel at that form–this was a decided exception). There are no really great bridges in Philadelphia for him to walk over (the memorable George Washington Bridge opening of The Hunter really did come from Westlake’s own personal experience), but you see how the personal angle of Parker’s revenge–the sexual angle, a more personal type of professional betrayal than Greene wrote about in A Gun For Sale–could come from this. The idea that you might need to even a score, balance out a sheet, before your mind could stabilize itself. And the trip across country to get it done. But Parker would never run away from himself, like Kenneth does. Parker wouldn’t need a Tillie to tell him about black pudding.

So that leaves the third novel, that came out the year before Black Friday, from a writer who did specialize in heist stories (maybe the first to do so), who also had a bunch of his novels adapted into films. He was quite popular at the time, but in my humble opinion, Lionel White was never much of a writer.

Well, so what? Any writer can have good ideas, which then influence other writers. White’s main attribute, what brought him fame for a short time, was that he’d worked the crime beat for a newspaper, and he had some actual knowledge of criminals, which gave his work an extra touch of verisimilitude. But I’ve read several books of his, and at his very best–he’s just a bit more than mediocre. What the hell, he’s dead, the truth can’t hurt him now.

I’ve already talked about The Snatchers. I had to, because Westlake cited it as an indirect inspiration for the third Dortmunder novel, Jimmy The Kid. He was fascinated by the fact that some French hoodlums had used that book as a blueprint to do a real kidnapping. I read it to see if Westlake had borrowed directly from it. He hadn’t. For that book. But in reading it, probably long before he wrote Jimmy The Kid, he would have seen yet another character whose potential he might have felt was underutilized in the book.

Pearl thought, God, he isn’t really human. He’s like a lean tawny cat, crouched and waiting.

His leather spare face was ascetic in its immobility, and the prematurely white hair, with its cowlick over one eye, lent him the contradictory look of a little boy who had suddenly grown too old. He had charm, but it was a dangerous sort of charm. The mediocrity of his lean average-sized body was belided by the dynamic quality of his astringent personality.

That’s a description of Cal Dent, and it does sound a lot like Charley, doesn’t it? Probably not a coincidence. Goodis was not above the odd bit of honest theft himself, but Charley’s a much more compelling and complex character than any of White’s heisters (and a fair bet that White had lifted a few things from Goodis before now). Still, White did touch on something there–the non-human quality. The comparison with a beast of prey that keeps coming up, over and over again–and yet never gets developed the way it needs to be. Still, there are some interesting things about Dent. Like his attitude towards sex.

Dent had known many such girls, but few as attractive as Pearl. Cal Dent was that unusual sort of man–the sort that can be found fairly often among ex-cons–who could take his sex or leave it. Pearl attracted him, it is true, but there was nothing exclusive or personal in the attraction. To Dent, she was merely another woman, to be had or not to be had, according to the circumstances of the moment.

The man was able to put aside all thoughts of women, irrespective of their proximity, during those times when he was immersed in a job. The fact that at this time he was in the middle of the biggest thing in his life precluded any possibility in his taking more than a purely academic interest in her.

So that’s what I’ve got so far–and what does it amount to? Not much. Have I proven anything? Not really. Westlake knew all these books, we can be sure. He actually went to some pains to make sure we’d be sure. But are any of these characters Parker? Not even close. Did he take anything from these books and stories that he couldn’t have gotten elsewhere? Probably not. Could I just be starting at shadows? Quite possibly. If I’d read ten times as much crime fiction as I currently have, I’d have read maybe a tenth as much as Westlake did. I haven’t proven a damned thing.

But my point stands. As does his. Parker was always there, long before Westlake started typing the manuscript that became The Hunter. He says he saw hints of the character in many places, many writers, never quite fully manifested, but waiting–waiting for somebody who could bring him to full fruition. The statue imminent in the marble. Waiting. Waiting for Stark.

There’s one more thing, though. I think there’ll always be one more thing, but this one really bugs me. See if it bugs you too. Westlake mentions, in that Gregg Press intro, a fairly obscure 1950 western novel, The Desperado, by Clifton Adams (who also wrote a few contemporary noir stories for Gold Medal and others). They made a movie of that too (I get the impression it’s not a very faithful adaptation). He speaks glowingly of it. I knew I had to read it, and as luck would have it, it’s evailable. Five bucks. What could I lose?

Terrific little book. Did it influence The Hunter? Not even a little bit. I suppose a character the protagonist meets, an outlaw named Pappy Garrett, does somewhat resemble that character Westlake mentions, the morally neutral man who maybe helps the protagonist out for enigmatic reasons of his own. So there’s that. But anyway, it was a brilliant story of how a young man from a decent background becomes an outlaw himself.

It reminded me a whole hell of a lot of Charles Willeford’s 1971 work The Hombre From Sonora, aka The Difference. Probably because Willeford pretty directly copied Adams’ story, as he was sometimes known to do (if you have the time, compare his Wild Wives with the Robert Mitchum vehicle, Where Danger Lives, with a story by Leo Rosten). Do I know of a more original writer than Willeford? Not hardly. Did that mean he was above taking a story he liked and doing his own thing with it? I’m not sure any professional writer is above that. Vladimir Nabokov wasn’t above that.

Originality matters, but what is originality? Having an idea first? Any schmo can have an idea. Being the first to bring out the full potential in that idea? That’s more like it. And what Donald E. Westlake, writing as Richard Stark, did with the ideas he’d gathered from many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore, mingled with his own personal experiences and perceptions, was to make all the previous incarnations seem quaint and curious by comparison. Parker is far more than the sum of his parts, and that’s why he’s come to overshadow all his influences, whatever they may be.

But why did I bring up The Desperado? Why did Westlake? Remember what I said about how he points one way, but his eyes go another? He also mentions the sequel to that book–A Noose For The Desperado. I read that one too. It seemed prudent to do so. He was on the money, as usual–it’s an inferior sequel, that tries to resolve the protagonist’s conflicts, and somehow diminishes him in the process.

Few and far between are the writers who can follow a book like The Hunter with The Man With the Getaway Face. And another twenty-two brilliant books after that. The protagonist of Adams’ book was all used up by the end of the first story, and there was no reason to bring him back. But even so, there’s a passage very early in it that made the hairs on the back of my neck stand up on end. Maybe it did the same for Westlake as well. You tell me.

The hero, as I said, is a young man from a respectable background, son of a small Texas rancher, who was drawn into the life of a gunman by the oppression that followed the end of the Civil War (obviously he’s not much concerned with the oppression that came before the Civil War, but that’s the western genre for you).

As the second book begins, he’s killed a few too many men, he’s on the run from the law, and he’s taken refuge in a small border town in Arizona. A Mexican girl gives him a shave and a haircut, and he looks at himself in a mirror for the first time in a while. Looks into his own eyes.

I studied those eyes carefully because they reminded me of some other eyes I had seen, but I couldn’t place them at first.

They had a quick look about them, even when they weren’t moving. They didn’t seem to focus completely on anything.

Then I remembered one time when I was just a sprout in Texas. I had been hunting and the dogs had jumped a wolf near the arroyo on our place, and after a long chase they had cornered him in the bend of a dry wash. As I came up to where the dogs were barking I could see the wolf snarling and snapping at them, but all the time those eyes of his were casting around to find a way to get out of there.

And he did get out, finally. He was a big gray lobo, as vicious as they come. He ripped the throat of one of my dogs and blasted his way out and disappeared down the arroyo. But I heard later that another pack of dogs caught him and killed him.

Nobody runs forever. But The Hunter will.

You want to see how far it’s run to date? Check this out.

Fascinating reading. Thank you, this gives me plenty to think about, and some titles to put on my “read, someday” shelf.

One writer who began in 1960 in paperback, in a different genre (but an adjacent one, I think — he made it into Murder off the Rack), is Donald Hamilton. I wonder how I’d react to his books now with my present sensibility (I got started on them by my father but then went on to read most of the Matt Helm series as it appeared), but I bet I would still think he wrote exceptionally well. I’m not proposing any influence in either direction, though.

I’ve yet to read any of the Matt Helm spy stories. I grew up watching the movies on TV. I am well aware the gap between them and the originals is far vaster than the gap between Ian Fleming and the 60’s Bond films. But I wonder if I could ever fully shake off the image of Dean Martin singing and swinging his way through a bevy of bodacious babes. To add to the confusion, one of the bad guys the movie Helm had to fight (in Murderer’s Row) was played by Tom Reese, an actor who appeared in The Outfit, who I thought was better suited to play Parker than Robert Duvall.

I tend to doubt Westlake got much, or anything, from Hamilton. Why? To the best of my knowledge he never mentioned him. Westlake was an honest thief. Like Parker. He wouldn’t take much from any writer without finding some way to credit the influence. True, I don’t know of him mentioning W.R. Burnett, but seriously–why bother? EVERYBODY in that genre was influenced by Burnett.

I still have only the mildest of interest in the Parker novels (despite telling my wife that those are the stories Westlake will be remembered for), but a very interesting post. I may give Rabe a try, however. That silly title makes me laugh.

I assume you mean Kill The Boss Goodbye. That one they can never make a movie of now, because Robert Ryan is dead. Though then again, maybe John Slattery. There are sillier titles at the multiplex every Friday, so that’s no problem.

I have loved this digression, even if I haven’t had much to contribute to the comments. This is a fascinating exploration, and I suspect you’re right that we’re barely scratching the surface. I wonder about Davis Grubb, whom I haven’t read, but Mitchum’s performance in the movie adaptation of his most famous work comes to mind. Reverend Harry Powell is not Parker, of course (he’s too loquacious, for one thing), but there’s a certain coldness in his eyes…

Mitchum’s performances in Night of the Hunter and Cape Fear would certainly put him high on the list of actors who could have played Parker. I haven’t read either of the books those films were based on, though it’s quite probable Westlake did. Both characters tend to do things that don’t make sense, and to sort of self-consciously revel in their own evil, which is not very Parker-esque. I couldn’t say if anything in those books influenced him.

I don’t doubt Westlake one bit when he said he originally envisioned Parker as looking a bit like Jack Palance. But which Jack Palance? Not the graceful tortured talkative film star he plays in The Big Knife, though Westlake did reference that film in the third Holt novel.

No, I’d say it was this one. Only with a lot less smiling.

The 1955 remake of High Sierra. Which was in turn based on the 1941 novel by W.R. Burnett. There really is no escaping Burnett if you’re doing heist stories. And there is no escaping justice if you’re a Burnett heister. And after a while, doesn’t it get frustrating? It must have been really frustrating for Westlake. The same sad ending, over and over again. He thought he had to write his own version of it (without all the violin music), then Buck Moon came in like Victoria’s Messenger Riding, and gave him the reprieve. That was all the push he needed. He was going to write a different kind of ending. Over and over again. But never quite the same way twice.

Damn, missed an interesting little ‘coincidence’ (you know what Freud said). W.R. Burnett had a very busy screenwriting career on top of his novels and short stories, and he didn’t just adapt his own books. He was one of the two credited screenwriters on 1942’s This Gun For Hire, with Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake. The other was Albert Maltz, who would later be one of the Hollywood 10. I never noticed this before. What do you think the odds are that Westlake didn’t notice? Yeah, probably not great.

There really should be more out there about Burnett–he may not have been one of the more enduring novelists of his era, but he casts one hell of a long shadow via his connection to Hollywood.

From our point of view these three books are very influental (Rabe is less so, but any mystery fan knows that Rabe was one of the best GM writers). One can assume that they influenced everyone in the field. Though it may not be so. Sometimes a bif work passes you by, but some obscure novel gives you an idea. I’d say Rabe’s influence as an inspiration. Rabe showed how one can write series novels, how one can write lean and mean short paperback novels about outlaws.

Rabe only wrote one series character, Daniel Port, and Westlake thought those books mainly didn’t work very well (and having read them all, I have to agree). They influenced him more with regards to what not to do, although he certainly did recycle elements of them in his own work, as I’ve mentioned before. And pretty nearly always improved on whatever he emulated.

But again, stylistically, Westlake said Rabe was a huge influence on him. Not so much in thematic or story terms. Probably the most Rabe-like novel is The Mercenaries. And yet that’s written in the first person, which Rabe almost never used. Same for Killing Time, which is also a book that ends in defeat. And then came 361, and The Hunter, and Killy. Westlake began to rebel against the notion that the outlaw has to lose in the end. It wasn’t only Bucklin Moon telling him not to kill Parker off. That was just a wake-up call that he could write the endings he wanted to write and still get published. Even if his hero was a villain.

Up to that point, only Highsmith, perhaps the ultimate original in crime fiction, had done that. And I would tend to think The Talented Mr. Ripley didn’t sell very well at first (or else why did she wait so long to write a sequel?). The Name of the Game is Death, which I and many others would now say was the quintissential Gold Medal crime thriller, was something of a flop, though many recognized its merits at the time.

Even to a large portion of the audience for stories with violent criminal protagonists, it didn’t seem right when these characters remained alive and defiant at the end. But Westlake somehow made it seem wrong for Parker not to live, not to (usually) win, not to get away clean, twenty-four times over the course of nearly forty-five years. He just made that seem like the natural course of events. And Parker seems to have no idea he’s defying any moral standard. Because he lives by an alternate morality. That we the readers are forced to accept, at least while we’re reading the books. Ripley thinks of himself as evil. Parker thinks of himself as–different. And he looks at us, and thinks how unfortunate we all are to be this way, wanting one thing, doing another. Divided against ourselves in a way he never has been.

Lots of people wrote lean mean short paperback novels about outlaws. That was a genre to itself for a while, as Gold Medal and other publishers reacted to the likes of Horace McCoy, James M. Cain, and Edward Anderson. Rabe wrote good books–books that were a cut above most of what Gold Medal and other such publishers typically produced. But he mainly wrote books about protagonists who would be defeated by life, and by tragic defects in their character they couldn’t see until it was too late. Westlake wrote books about protagonists who mainly came out on top, because they made better choices–because they found out who they were.

But in Parker’s case, he just knew who he was. The tragic defects would be in the characters of those who worked with him, or came up against him in some way. This should make Parker uninteresting, predictable, and he’s anything but. He was a protagonist who could never be fully explained, never fully summed up, and therefore remains fascinating to this day. If I could find each and every last book and story and film Westlake drew upon to write The Hunter, I still would have found nothing more than the raw ingredients. The ingredients are not the recipe, any more than the map is the terrain. The whole is more than the sum of the parts.