“Sara,” she said, as they started off.

“I’m Jack.” They walked between the lines

“I remember,” Sara told him, with a faint edge in her voice.

“Don’t kick me, lady,” Jack Ingersoll said, “I just left my bowels back there.”

“What was all that?”

“Every morning at ten A.M.,” he said redundantly, “the editors, of whom I am at least one, go to that shrine back there and lay thirty story ideas at the feet of–”

“Thirty! Every day?”

“Believe it or not,” Jack Ingersoll said, “I came here as a young and beautiful woman. Much like yourself.”

She looked sharply at him, but somehow the remark hadn’t had the quality of a pass, or a compliment. That left it unanswerable, so Sara continued beside him in silence.

The ordinary English public did not want thoughts but sensations. I had begun to edit the paper with the best in me at twenty-eight; I went back in my life, and when I edited it as a boy of fourteen I began to succeed. My obsessions then were kissing and fighting: when I got one or other or both of these interests into every column, the circulation of the paper increased steadily.

From My Life and Loves, by Frank Harris

Throughout the 1980’s, Westlake kept trying to break the mold he’d been cast in, resulting in many interesting books, but little in the way of tangible success. People liked Parker, people liked Dortmunder, people liked Comic Capers (whatever that means). Parker was incommunicado until the 90’s, Westlake couldn’t write Dortmunder all the time or he’d go crazy, and he’d written about all the stories he could take about directionless young males who get into trouble, meet a fetching female, and find themselves.

He liked writing foreign intrigue (Kahawa, High Adventure) but the book sales had been disappointing. He’d really enjoyed satirizing the publishing industry, but you can only bite the hand that feeds you so many times before it gets jerked away. He’d tried a new series character with Sam Holt, and it had not gone as planned. A male wish-fulfillment fantasy where the hero is deeply ambiguous about his fantastic life was tough to pull off.

Maybe time to try writing from the other perspective? A female protagonist? He’d done lots of those back in his days of writing pseudonymous sex books, and his political thriller Ex Officio, with its enormous cast of characters, was more or less centered around the brave and likable Evelyn Canby. Interesting female characters were never hard for him, but he had never really tried to write a mystery novel where the main protagonist was a woman.

He’d clearly enjoyed writing Bly Quinn, Sam Holt’s west coast girlfriend–blonde, brassy, brilliant–very much the ingenue, but with an edge to her. Bly was a writer, like him–that made her easier to identify with. Okay, so take a version of that character, less experienced, still finding her feet. Put her in a strange situation, that would test her resourcefulness–and her character. And of course put her in some kind of danger, like he’d done for all the picaresque protagonists of his ‘Nephew’ books (except hers would not be the only POV, so this would be written in the third person).

And he’d give her a love interest who was a sort of Ex-Nephew. A reformed idealist, a wounded romantic; somebody who used to believe in principles and fighting for the common good, and all that hopey-changey stuff, before Life had its way with him. Two people at different stages of their respective learning curves. Nephew and Niece, jousting their way towards love, in the midst of doing their jobs and fine-tuning their identities. Wouldn’t that be incest? I suppose since all his characters are technically his children……

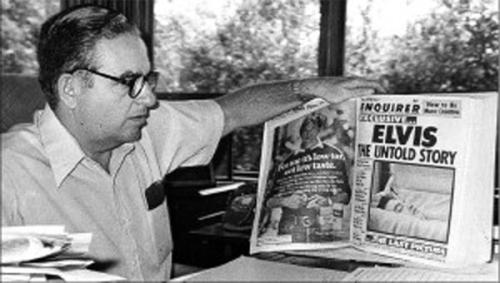

And he could still do another satire of the publishing industry–just another kind of publishing. The kind that is basically already a satire of itself. The Supermarket Tabloid. Who does these things? Where do they get their ideas? How do they live with themselves? How do they know themselves? This has been a ripe source of comedy for generations now, as two images I posted up top can attest.

There can be no doubt at all which tabloid in particular caught Mr. Westlake’s attention, as he pushed his grocery cart into the checkout lane. Started up not quite a decade before this book came out. Published by Generoso Pope Jr.–yeah, try improving on that name, Mr. Westlake. Should I mention that the Jesuit college I attended had an auditorium named after the generous Mr. Pope, a benefactor of my alma mater? (Or possibly his slightly more respectable dad, who had the same name, I never asked.) Nah, why bother.

Headquartered in Boca Raton, Florida, along with its sister rag, the National Enquirer (in essence, the tabloid featured in this book is a diabolic admixture of the two), this curious publication first saw print in 1979. And the world of ‘news’ would never be quite the same again.

You see the inherent problem to writing this? Westlake surely did. No matter how wild and wacky he got, the source material would always top him. I mean, these are relatively tame examples I’ve posted up above. I didn’t even mention Bat Boy. Did you know he led us to Saddam Hussein?

Anyway, Mr. Westlake was well aware of the large legal staff employed by that publishing group. His experience with Scott Meredith would tell him not to underestimate such a personality’s (if you want to call it that) capacity for small-minded vindictiveness. So a small disclaimer opens the book.

Although there is no newspaper anywhere in the United States like the Weekly Galaxy, as any alert reader will quickly realize, were there such a newspaper in actual real-life existence its activities would be stranger, harsher, and more outrageous than those described herein. The fictioneer labors under the restraint of plausibility; his inventions must stay within the capacity of the audience to accept and believe. God, of course, working with facts, faces no such limitation. Were there a factual equivalent of the Weekly Galaxy, it would be much worse than the paper I have invented, its staff and ownership even more lost to all considerations of truth, taste, proportion, honor, morality or any shred of common humanity. Trust me.

I really don’t think Ambrose Bierce (or Messrs Hecht, MacArthur & Waugh, how’s that for a law firm?) could have said it any better. Since Bierce worked for William Randolph Hearst a while–one of the fathers of Yellow Journalism, who would start actual wars to boost circulation (along with the guy the most esteemed prize in journalism is named after)–I greatly doubt any modern skullduggery of the press could have shocked him. I trust we’re all beyond shock now, in the era of 24/7 cable news. With that shared sense of inurement taken as a bitter yet inescapable fact–shall we proceed?

Sara Joslyn, not too far into her 20’s, her dark blonde hair long and straight, with legs to match, is driving down a strangely empty highway just outside Miami, when she sees a car stopped by the road. She’s a reporter by trade, recently had her first newspaper shot out from under her (the death of print journalism just then becoming a thing). Nosy by nature, much like Pandora, Nancy Drew, or Bluebeard’s wife, but with a journalism degree to legitimize it. She goes back to check it out. There’s a man in the front seat. He’s been shot in the head. “Oh jeepers,” she says. The story won’t be as G-rated as her language.

She reports the crime to the security man at the gate of her new employer, the Weekly Galaxy. We’ve already discussed what they do. She’s not crazy about the gig, but they are offering an enormous starting salary (35k per annum, and remember, it’s the late 80’s). Her employment alternatives are thin on the ground right now. How bad could it be?

She’s got about half a dozen novels in the works (show me a journalist who doesn’t), one of which is called Time Of The Hero (at least it’s not A Sound of Distant Drums). She doesn’t really know who she is, and at that age, who does? Maybe this job helps her find out. If she lives long enough.

She stumbles into a daily ritual at the Galaxy–as mentioned up top, every editor has to submit thirty story ideas–per day–to ‘Massa’, otherwise known as Bruno DeMassi, the publisher of the Galaxy, and for all his plebeian origins, the Westlake-ian equivalent of Lord Copper from Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop. He Who Is Not To Be Questioned. An absolute dictator, as capricious as he is uncouth–and so powerful that he was able to have a twelve-mile four-lane highway built to service his corporate headquarters, even though there’s absolutely nothing else there for it to service.

That’s why there was no traffic when Sara arrived. That’s why there were no witnesses to the murder. Which absolutely no one at the Galaxy gives a solitary shit about. Not their department, unless he was murdered by aliens, or Bigfoot. All they have to do is come up with those thirty ideas a day and not have too many of them red-penciled (ie, shot down) by their boss. Somebody (namely our male lead) suggests the Galaxy clone a human being. This conversation ensues:

“Which human being?” Massa asked. “Man or woman?”

“Well, I was thinking of a man originally–”

“Where’s the cheesecake?”

“We could do a woman, of course,” Jack conceded. “But remember, sir, it’s going to be a baby for–”

“A what?” Massa glowered. “You mean we don’t start with a person?”

“No, sir,” Jack said, with every appearance of calm. “Clones have to be born like anybody–”

“You mean we got a baby around here for twenty years?”

“Well, we don’t have to–”

Binx, who at odd moments tried to help other people, even though no one ever tried to help him, said “It might be a mascot, sir.”

“Oh, no,” Massa said, with a negative wag of the beer bottle. “We had that goat that time, and it didn’t work out. A baby isn’t gonna be better than a goat.”

Worse, really, but hardly the time to bring that up. Binx Radwell, in case you were wondering, is Jack’s best friend at the paper, which isn’t saying much. A born loser, though his day will come, in a subsequent book. Where do these Wasp boys get those first names from? We’ll talk more about him later.

Lord Copper aside (I don’t know who the model was for him, never even read the book–somehow Waugh is not me), I’ve already mentioned the real-life model for Massa– Munificent Pontiff, or whatever it was. Here’s a picture of him.

(Before I bothered to look any of this up, just from reading the book, I’d head-cast DeMassi as Danny DeVito–and the weird thing is, he’d have worked just as well for the role in the late 80’s as he would today, not that anybody’s making a movie, but it’s good to know he’s still available if they ever do).

So Sara, like Alice through the looking glass, is our entry-point to this topsy-turvy world. Nobody has offices, they have ‘squaricles’, which is to say desks with lines drawn around them to designate the non-existent walls, and everybody is expected to pretend the walls are actually there. The phones don’t ring, because there’s so many of them and so many incoming calls that everyone would go mad as a hatter if they were not instead fitted with flashing lights (Actually, hatters in the days of mercury poisoning were probably quite unexceptionable persons compared to your average Galaxy staffer).

Only Massa has an actual office, but it’s located in a large service elevator, fully equipped with desk, mini-fridge stocked with beer and etc, so he can move unpredictably from floor to floor, keeping an omniscient eye on everyone, and nobody knows when the door on their floor might open and the Voice of God might issue from within, along with the occasional belch. I don’t know if the real Generoso Pope Jr. really did this, and I don’t want to know.

It’s a cutthroat working environment, with each editor assembling a team of quack I mean crack reporters, and each team striving to outdo the others, which means getting more stories into each edition (if you start getting too few, that’s where throats start getting cut). There is, believe it or not, actual fact-checking involved in this process, but it’s done mostly for tedious legal concerns rather than for veracity’s sake. Did I just say ‘mostly’?

The stories involve weird (and quite possibly fatal) diets, strange scientific discoveries the staff has made up that they’ve gotten some tame expert to half-heartedly verify (a huge part of the workday involves getting ‘money quotes’ from such people to cover the paper’s inquiring ass), the colorful activities of various paranormal beasties, but of course most of all the private lives (and deaths) of celebrities.

Massa has become obsessed with one such luminary in particular, John Michael Mercer, star of the hit television series Breakpoint. Who for reasons I’m sure we could not begin to guess hates the Weekly Galaxy with every charismatic fiber of his being, and is constantly firing all the people working for him that are actually working for the object of his truly puzzling hatred. What, a person can’t moonlight? You might think such industry would be commended, but show people are notoriously eccentric.

So Jack and Sara meet, and the proverbial sparks fly. They’re attracted to each other immediately, but she’s assigned to his team, and his first concern is that she do her job the right way, which at any other paper would be the wrong way–she needs some retraining, and occasional restraining.

She’d be willing enough to date him if he played his cards right (even though such fraternization is technically frowned upon at the Galaxy), but his caustic domineering manner rubs her the wrong way (much as he’d privately like to rub her in more pleasant ways). Sara Joslyn is nobody’s little plaything, and she’s determined to prove she can be as scurrilous a scandal-monger as any man. Over the course of the rest of the book, she sets about doing exactly that. And Jack, his conscience not quite as dead as he’d like to think, watches this pulchritudinous pilgrim’s progress with mounting concern. Oh grow up, you know what I meant.

Jack’s reminiscent of many earlier Westlake protagonists, such as Eugene Raxford of The Spy in the Ointment (the activist thing), but also that scurrilous scoundrel Art Dodge of Two Much, most of all in his bickering yet somehow sibling-like relationship with his secretary, Mary Kate. Jack’s somewhere in-between–more cynical than Eugene, less caddish than Art. Early on, he muses to himself about why some small voice within him says ‘fire the broad’ after Sara hangs up on him because he forgot her name. “You want to save her from corruption,” Mary Kate suggests. “No, that can’t be it.” Later, he says out loud, “Maybe I hate women.” Mary Kate tells him he’s not that selective.

There is also a professional nemesis for Jack (who by extension becomes one for Sara)–the most successful editor at the Galaxy by far, Massa’s pet pupil, one Boy Cartwright, scandalmonger supreme–incurably English, 40 to Jack’s 30, dissolute, degenerate, and dead to all concerns other than material ambition. Which means getting his stories into the paper, which he does with nauseating frequency.

(Westlake goes to some pains to explain that because gutter journalism of the very lowest order is commonplace in the UK and Australia, Brits and Aussies are commonly found in the ranks of the Weekly Galaxy, having been so well-drilled for its comparatively innocent little excesses in the slimy trenches of Murdochville. Would that News of the World phone-hacking scandal have come as any kind of a shock to Donald E. Westlake? Don’t make me sneer.)

Sara finds this out for herself, when she’s given a special assignment. This comes as a reward for helping Jack find out a juicy tidbit about John Michael Mercer, who has thrown over all his prior bimbos I mean ladyfriends for a shockingly sweet and wholesome girl named Felicia who has the temerity to have absolutely nothing at all wrong with her.

The assignment is a trip to the sacred heartland of America (or whatever Indiana may be). She’s to cover the 100th birthday of identical twins, living in a nursing home there. To provide back-up, she’s given three Australians, and let’s just say Westlake had way too much fun writing them.

Whitcomb, Indiana, on a Tuesday in mid-July. Even the dogs were bored. A couple of them lying around in the shade under Edsels and LaSalles didn’t even look up when the Trailways bus groaned to a stop in front of the Rexall store, farted shrilly, and opened its door to release the big-bellied sweat-stained driver and the Down Under Trio. Bob Sangster scratched his big nose, Harry Razza patted his deeply wavy auburn hair, Louis B. Urbiton gazed about the somnolent downtown of Whitcomb in mild amaze, and the bus driver opened a bomb-bay door in the rib cage of the bus to remove the Aussies’ battered and disgusting mismatched luggage.

“So this is America,” Harry Razza said.

“Can’t say I like it much,” Bob Sangster said.

“Oh, good,” said Louis B. Urbiton, “there’s a pub.”

“Bar,” Harry corrected.

“Bahhhh,” Louis amended.

“Have a nice day,” the driver said, and remounted his bus.

The Aussies stared after him, in astonishment and shock. “What?” demanded Bob.

“I call that cheek,” Harry said.

The bus door snicked shut. The bus groaned away. The dog under the Edsel opened one eye, saw the six well-polished shoes of the Aussies, decided in his doggy innocence that these must be acceptable functioning members of society, and closed the eye again.

So they proceed to do what they always and invariably do, shameless raconteurs that they are, the life of every party–get everyone on their side simply by temporarily relieving everyone’s deep boredom with free drinks and improbable yarns. The only one in the ‘bah’ who isn’t laughing at their antics is a disreputable bag lady hanging out there. Sara arrives, and demands to know where their photographer is. Guess.

After badgering the local master baker (oh shut up) into engineering a twenty-foot birthday cake, Sara is horrified to learn one of the twins has chosen this precise moment in time to quietly expire. They were both vile cantankerous lecherous old coots who didn’t even like each other, but that’s neither here nor there. The story calls for two beaming oldsters to be photographed in close proximity to an enormous cake. What actually happened is not the story. The story is what was decided upon by editorial before any of them set foot in Whitcomb, and her job is to deliver that story, and no other. No twins means no party, no cake, no free booze. Massa says.

So oddly anticipating Weekend At Bernie’s, Sara, while explaining the debacle to Jack over the phone, and hearing Massa’s stern decree shouted from the elevator, suddenly changes tack and says the dead twin has been miraculously revived, not to worry, everything’s great. She delivers the story, twins, cake, party and all–who’s to know the dead twin is actually Bob Sangster, cunningly made up to look like the deceased sibling, with the bag lady photographer shooting him in such a way as to conceal the artifice, and the living twin threatened by his fellow inmates not to raise any fuss about it, because they want free cake and liquor, as do all decent god-fearing Americans, except maybe in some of the dry counties.

And Jack, who knows Sara lied about the twins, even though she staunchly refuses to admit to it, and should by all rights be applauding his reporter’s ingenuity, is instead strangely troubled by it. Is he ruining this girl? Without even going to bed with her first? Where’s the fun in that?

So Sara pulled off a minor triumph, which is all well and good, and makes for a nice two-page spread, but pales before the significance of John Michael Mercer’s rumored impending nuptials to the lovely Felicia, which must of course be covered in depth by the Weekly Galaxy (Massa wants), even though Mercer would much rather see all of them dead, and has said as much. His and Felicia’s goal is a small private ceremony in a beautiful and secluded location, with no press of any kind (and a few hundred close friends and family members present, and the press still encamped nearby, because after all, major TV star). The Galaxy‘s goals are less than fully compatible with this deeply selfish agenda. Let the games begin.

And the games are multi-tiered, because even as Mercer fights for his right to party privately, Jack’s team, which found out about Felicia first, has to fight Boy Cartwright for the story. Massa encourages such high-spirited competitiveness among his editorial teams. Boy has a mole in their ranks, and Jack puts Ida Gavin, his top reporter, in charge of smelling the foul subterranean varmint out. He knows it’s not Ida, because she has an ancient blood vendetta against Boy for having seduced and abandoned her, years before, purely in the line of duty, of course. Jack’s pretty sure it’s not Sara who’s giving Boy the goods, but no one is above suspicion unless they hate that bilious Brit at least as much as he does.

Sara is enlisted to infiltrate an elite employment agency Mercer has contracted to replace his repeatedly infiltrated domestic staff, and does a great job with the interview–very nearly fools the sharp-eyed proprietor into assigning her to Mercer, but with an almost supernatural canniness, he spots her as a ringer (neither knowing or caring which newspaper or magazine hired her), and shows her the door. Frankly, I don’t know what Jack was thinking there, since he identified Sara as a Galaxy reporter to Mercer in a Miami restaurant earlier in the book, as part of a ruse–so wouldn’t she be recognized? Perhaps a plot hole, but a moot one, since the intrepid interviewer sniffs her out, complimenting Sara on the smoothness of her delivery. Says she’ll really be something once she gets her growth. She’s suitably flattered. Not even the least bit embarrassed. She’s getting her growth by leaps and bounds.

And the name of this paragon of personnel, this maid-vetter to the rich and famous? Henry Reed. Huh. Why does that name sound familiar? Oh right!

So really you could argue he’s still baby-sitting. And why is Westlake making this reference? Well, Keith Robertson also wrote murder mysteries under the name Carlton Keith, you see. The first two Carlton Keith novels were published by the Cock Robin imprint of Macmillan, where Richard Stark briefly held court with the first three Grofield novels. And Mr. Robertson (like his bespectacled young protagonist) was living in New Jersey at around the same time as Westlake. That might well explain it. It’s not really that important, but sorta neat, wouldn’t you say?

And in the midst of all this, Sara is still trying to solve the murder mystery that started this book. She gets sidetracked a lot, but it keeps nagging at her. She finds out, to her confusion, that the story never appeared in the local papers–okay, probably a drug killing, not worth mentioning in the greater Miami area. Except then she finds out the police were never notified.

And the security man at the gate she reported the crime to has himself disappeared–without a trace. And Sara realizes–the murdered man was on his way to the Weekly Galaxy. On that highway, he couldn’t have been going anywhere else, until he got rerouted to the Great Beyond. And since she’d seen nobody driving the other way when she herself made that passage, only a Galaxy employee could have been the murderer. The plot thickens!

But such paltry matters cannot long distract her (after all, the only reason there’s a murder mystery at all is that this book is being published by The Mysterious Press). The Galaxy doesn’t cover murders, unless it’s Bigfoot murdering the Loch Ness Monster (I’ve heard there’s bad blood there). The Mercer Wedding takes priority. And her growing affection for Jack, her desire to impress him with her brilliance, and that she does, when she snatches victory from the slavering jaws of Boy Cartwright.

Boy had won the right to cover the wedding away from Jack’s team, since a well-placed spy on Mercer’s staff (even Henry Reed is only mortal–his books would have been so boring were that not the case) has revealed that the nuptials are to be held at Martha’s Vineyard. Still, Boy had to know about Felicia’s existence in the first place to gain this advantage, and as Ida Gavin triumphantly reveals, Phyllis Perkinson, Sara’s co-worker, friend, and roommate, is the spy.

Not just for Boy, either–he only got a hold over Phyllis because he found out she’s doing an expose on the Galaxy for Trend magazine (which sounds a lot like New York magazine, going by the description, and I rather suspect Westlake was more of a New Yorker man, but never mind that now). Not about the fact that they report things that are not true (that would be reminiscent of John Stossel’s legendary “Pro-Wrestling is Fixed!” segment on 20/20 that got him beaten up by an irate grappler), but rather the squalid inner workings of the paper.

Sara is furious at Phyllis, more than she would have imagined possible–how could she betray Jack Ingersoll, the man whose character Sara herself has never had one good word to say about? But that’s different. She’s not merely offended on Jack’s behalf, but on that of the paper she is feeling an ever-increasing loyalty towards–even as she wonders if she’ll be employable as a reporter on any other paper, if she stays there much longer. And she just saw poor Binx get his ass fired–saddled with a house, kids, and a wife who doesn’t give a damn about him, he’s been living right at the edge of his means, as overpaid people so often do, and she knows he’s tried repeatedly to get a job in serious journalism, only to be laughed out of each and every office.

She has it out with Phyllis at the apartment they share, and Phyllis (who comes from Old Money, don’t you know) has the nerve to pull the First Amendment on her. These people are a threat to decent news media everywhere! To which Sara sarcastically asks if Froot Loops (sic) are a threat to sirloin steak. I guess that depends on whether you can afford the latter, and actually neither is very good for you, but we’ll let that drop.

With a pitying smile, Phyllis said, “So the Galaxy is just a harmless enterprise?”

“No, I don’t mean that,” Sara said. The memory of Binx Radwell leaving the office this afternoon, briefcase and shopping bag hanging from his arms, brown-uniformed armed guard trailing him, employees along his route turning their backs and studying reference books and doing anything they could not to meet poor Binx’s eye, was still fresh in her mind. “The Galaxy is very harmful in one way,” she said. “It eats its young. That part scares me sometimes, but I think maybe I’m smarter and tougher, and it’ll come out all right. But our arthritis cures and our interviews with people from outer space don’t hurt the First Amendment, for Pete’s sake!”

“We have a difference of opinion,” Phyllis said, shrugging again.

Sara said, “What it comes down to is, you want to do the same kind of muckraking we do, but you want to feel holy while you’re having your fun. Like television movies about the evils of teenage prostitution.”

“Isn’t teenage prostitution evil?”

“So are the crotch shots on TV.”

“Oh, really, Phyllis said airily, “if you can’t see the difference between the Weekly Galaxy and Trend–”

“That’s right, I can’t.”

(And I rather think Mr. Westlake was bothered by how little difference there really was–and is–but more on that in Part 2, and of course there’s going to be one).

So she concocts a plan involving Betsy Harrigan, a beautiful red-headed telephone repair girl I mean person that Sara met earlier, and she’d wanted to do a story about Betsy, but she couldn’t quite find the right Galaxy-esque angle. She finds it (a seemingly prophetic dream the girl’s mother had that prefigured her daughter’s future employment). The girl happily reciprocates the favor (her mom is a devout Galaxian) by bugging John Michael Mercer’s phones.

So in no time at all, Sara’s got far more and far better intelligence than the elderly Asian gardener in Boy’s employ could ever hope to obtain. So she goes to inform Jack at his modest surburban home (modest because he’s socking away most of his outrageous salary against the day Massa cans him), and finds him baking of all things, drowning his sorrows in cake dough (you never know about some people). She tells him they’re going to Martha’s Vineyard, and explains how she made it happen. He explains they still need to get a personal interview with Jack Michael Mercer (Massa wants). Well, that’s going to be a little harder. Also possibly fatal. But the bug has well and truly bit her, and she says they’ll find a way.

“What I really think is,” she told him, “this is fun. This is the most fun I’ve ever had in my entire life. Absolutely nothing in the world matters except that we beat Boy Cartwright to the John Michael Mercer wedding.”

“Grinning crookedly,” Jack said, “Not even your murdered man beside the highway?”

Sara laughed. “On what series is he a regular?”

“None.”

“Then forget him! We’re on our way to Martha’s Vineyard, that’s all, and whatever Massa wants from us, we’ll get it!”

“By golly, Sara,” Jack said, gazing upon her in wonder, “you are not the girl who walked into the Galaxy office last month and told me you were a real professional reporter.”

“You’re darn right I’m not,” she said. “I don’t have a serious bone in my body.”

“I want to put my arms around you,” he said looking down at himself, “but I’d get you all over flour.”

“Flour from a gentleman is always nice,” she said.

Asterisks follow. Then, as they lie (and lie and lie and lie) post-coitally in Jack’s bedroom, he pops the question–“Tell me one thing. Were those twins legit?” “Of course they were” she prevaricates easily. Too damned easily. And he knows it. This is the problem. But it can wait until Part 2, which shall arrive on deadline, sometime next week. The veracity of my statement vis a vis the matter at hand may be fully relied upon. Words to that effect.

(Part of Friday’s Forgotten Books)

I’m so glad we’ve arrived at this one. We’ll have lots to talk about, I’m sure, and I can’t wait.

I’ll just note parenthetically now, because it pertains to Part 2, that I experience a letdown as we approach the end. Not the very final chapter (though I do hear part of my brain asking “Really? That would work?” — no big deal though). But the sequence right before it, partly for structural reasons, partly for what I can only call moral ones, inappropriate as I know such considerations are to a no-holds-barred satire.

But really, in proportion to the book as a whole, that’s minor stuff. Even as I read it when it was brand new, I knew it was a different Westlake road, and I thank you for laying out the background and reasoning for that so well. I also remember that this was the only D.E.W. that my father got to before I did. He brought it up during a phone call, and I remember feeling (along with the usual pleasure I always felt each time a new title appeared) a certain pride that my influence had finally made Dad such a fan that he noticed and remembered the name when he saw a bookstore display, and immediately bought it.

This is one of the few D.E.W. books my mother has read (my father, to date, has read none that I’m aware of), and this is because I could get it in a large-type edition, which she needed at the time (she had the needed eye surgery, so now I can just send her the latest Harlan Coben, and I just do not see what she gets out of those, but she’s not alone). It was clearly a pretty big seller for The Mysterious Press. They even had a book-on-tape version. And this is why there was a sequel. And for reasons we can discuss later, I’m not convinced that was a good idea, though it’s not a bad book, taken on its own merits.

I guess my problem with the penultimate chapter is that Sara has been out there working this murder case in her spare time, digging up clues, tracking down witnesses, and who gets to do the patented end-of-mystery speech, explaining what happened and why? Guess.

Westlake liked and admired women. I have no doubt he fully believed in the equality of the sexes (in fact, I rather suspect he’d have said most men would be damned lucky to be equal to the best women). But he was still a guy. From our earliest school days, us boys learn how to grab all the attention. We need it. How else are we going to impress the girls? 😉

Hah — good point about Jack being the one to explain things. I have to cop to being a guy too; that aspect hadn’t jumped out at me, shame on me.

Since we’re on it (and so I won’t have to revisit it later on), my issues with that chapter are (1) It comes as a letdown to me, after all the ostentatiously planted mentions of “body in the box” and how it’s the ultimate prize and nobody will explain it, it turns out to be… pretty much exactly what I would have guessed; no new revelation there. (2) The use of a false AIDS scare as a way to clear the house. I get it that these are reprehensible people who’ll use anything, and that the book satirizes our worst aspects; and I acknowledge that in a certain time period the widespread fear was real and justifiable, as nobody could guarantee how it spread before the research was done. But at the same time, my friends were dying, and it spoiled the overall good spirits of the reading experience to see that used as a mere cynical plot device. (By the characters without the author’s approval, I do understand. But still, the author thought it up too.) OK, having said that I can leave it alone now.

Ah, I see. I think the joke there is on the homophobes. People knew nothing about AIDS, and the less they knew, the more frightened they were. Which is how people are. And this is, above all else, a book on human folly and credulousness. It must be said that satire that doesn’t hurt anybody’s feelings is lousy satire. But I can see how you’d feel that way. He could have picked some rare disease, so then it would only be hurtful to a small number of people reading the book (and wouldn’t fit the premise of the narrative nearly as well).

I mean, how do you think people who have Rabbititis feel when they see Hare Tonic?

AIDS really seemed like The End for a while there, didn’t it? All plagues do, and then guess what? Not The End after all. Just a lot of little ends, each of which is catastrophic for those it touches. It was nothing compared to The Black Death. That doesn’t mean it’s in bad taste to enjoy reading The Decameron. Too soon?

I’m glad you figured out what the body in the box was, but I guess I didn’t read enough supermarket tabloids growing up. I was culturally deprived.

One other thing that occurred to me while I was rereading another favorite book last night (Sarah Caudwell’s last): This is one of many suspense books whose story was endangered by changing technology even as it was being written, and a hasty sentence has to paper over the reader’s predictable questions. In this case, reporters carrying typewriters around in 1988… OK, it’s too early for laptops, but it’s left to Sara why they’re not all at interconnected desktops, to be told that “Massa likes his people mobile.” Because this is the story, and whatcha gonna do?

(In the Caudwell, it was that a top executive thought that it was “ungentlemanly” for his subordinates to carry mobile phones. I’m sure there are other books that have to get around the existence of Caller ID, or whatever. It was easier to think up mysteries before we were all so interconnected.)

I interpreted that differently–in this case, what Massa wants is what Westlake still did, and went right on doing, for another twenty years, until he dropped. He’s not papering anything over–he’s intentionally being retro here.

I don’t know what actual ‘reporters’ wrote on at the Enquirer and WWN in the late 80’s–I seem to recall there still being some electric typewriters in use back then in the various offices I worked at. Everybody didn’t switch to word processors overnight, and word processors were pretty awful for a while there. Linked computers had certain security issues then (as they do now, only more so).

Certainly no mobile electronic devices that were worth a damn at the time. But that isn’t the point. The point is, he has an excuse to have his reporters still be using manuals, and that’s how he wants it. So that’s how it’s going to be. Period. Space bar. Carriage return. 😉

Sure, all of that is true. And as I (hope I) said, I don’t really mind this at all. But this particular point came to my attention because I was watching Season 1 of Lou Grant on DVD yesterday (just released this week! finally!), and in an early episode they refer to the VDTs (video display terminals) that were the coming thing — there were just a couple of them on the outskirts of the newsroom, while generally everyone was using typewriters. And then in Season 3 everyone switched over to VDTs (they shot a new opening credits sequence so we’d notice), and I remember all the approving newspaper articles noting that the change had happened at their papers at almost exactly the same time. That was in 1979.

Whatever the limitations of early word processors, the advantage of being able to zap your story back and forth between you and your editor, edit onscreen, and when finalized send it directly to layout, with never a need to retype or typeset, was huge. I’m not saying it all happened at once, or everywhere simultaneously, But a decade later, seeing manuals in use on a national tabloid, I as a reader found it noteworthy enough that I was waiting for at least some minimal explanation. Which is what I got. OK, no problem, I could then ignore it and continue to enjoy the book.

It’s a good observation, and Westlake was clearly aware of the technological discrepancy, but given what an oddball publication this is, I could honestly believe they’d stick to the old technology for a while. After all, what they’re printing isn’t really news–they’re making their own news. It’s a weekly newspaper, and the editors work closely with their teams to manufacture stories.

But mainly it’s just the author imposing his personal whims upon his creation, and extending his middle finger towards new technology, as he so often did.

I’m glad this is a two-parter, since I enjoyed this first post so much. As you mentioned, the story also appeared as a book-on-tape back in the day, and that’s how I convinced my wife to give it a listen. (She’s a horror fan, not a mystery reader.) She liked ‘Trust Me’ so much, we had to listen to the ‘Baby, Would I Lie?’ audiobook on our next long, long cross-country drive to see family. Both versions are a lot of fun and well done, if you have the time and inclination to given them a listen.

I was wondering if it would be a two-parter–it’s fairly long, but I’ve covered longer books in one installment. It comes down to how much I feel I have to explain the book before I get seriously into recapping and analyzing it. My reviews have been getting longer as the blog spools on, and I don’t know if that’s because the books are getting longer and more complicated, or because I’m just getting longer-winded. Probably both.

This is a great post. I read this book in the last year, my first Westlake in a long time. I wanted to rush out and get the 2nd book even though I have read it isn’t nearly as good. But I bet I would enjoy it.

I enjoyed it a lot, but it’s basically some of the same characters exploring a different world, and the story isn’t quite as strong. The Weekly Galaxy is at the periphery of that book, no longer central to the narrative, and I think the sequel suffers somewhat from that, but it’s an unavoidable problem Westlake had to face up to. And there are other problems I’ll talk about, but it can wait. That book came out in the 90’s, so you’ve got some time to read it before I review it.

Nobody has offices, they have ‘squaricles’, which is to say desks with lines drawn around them to designate the non-existent walls, and everybody is expected to pretend the walls are actually there.

What were you saying in the previous post about originality?

I had forgotten that (not the show, which I watched religiously for years). I suppose that could be the influence, but it’s pretty different, in that this is something management is imposing on the workers, not something the workers came up with themselves. Open work spaces have been a thing for a very long time, but the cubicle in its modern form only goes back to 1967.

With WKRP, the point is that Les has an inflated sense of his own importance (always comparing himself to Edward R. Murrow, even though Murrow was a flaming liberal and Les a sort of attenuated Cold Warrior, all paranoid and reactionary, but in a cute way–not so cute anymore, is it?). He’s drawing those lines in reality to indicate the lines he’s drawing inside himself.

Basically, the point here in this book is to emphasize the absolute supremacy of Massa, the only one with his own (mobile!) office. Everybody else, even the highest-ranking employees–still peons, living in a state of feudal bondage (only no sense of noblesse oblige, since anyone can be fired at any time for any reason). Boy Cartwright, the MVP, feels privileged to have a corner squaricle, so he has two actual walls. Jack zealously clings to his window squaricle, since it means he has at least one wall.

And everybody else guards their private space zealously, even though the reality is nobody there has any privacy at all. But they’re so intent on competing with each other, they’ll never have the guts to stand up to management and ask for better work conditions. When one of them gets fired, the others all avoid eye contact. Like failure is contagious. I wish I could say I don’t know what that’s like.

None of that is in WKRP, which is about tight-knit little family (they mean far more to each other than their real families), where everybody loves everybody, in spite of all the little slights and personality issues, and that’s been a well-established sitcom formula since at least the Mary Tyler Moore Show. Barney Miller was far and away the best of the bunch for my money. But it’s still taking something we really don’t like that much–namely work–and making it cuddly and sociable and humanizing and valuable. When in reality, it’s so often the opposite. (Sorry to be such a downer, but it’s fucking Friday, what do you want from me?).

Westlake despised office work. His entire life was a rejection of that kind of working environment. A rejection that for most of us isn’t practical. But it’s something you have to allow for in him. And you can’t say he doesn’t have some valid points to make about the working world we’ve constructed for ourselves.

Ah, Bartleby. Ah, humanity. 😦

Well after the fact, I can add one more potential influence to the list–

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scandal_Sheet_(1952_film)

Based on a novel by Samuel Fuller (who knew whereof he wrote when it came to gutter journalism), it likewise features a murder mystery within a narrative about a sleazy tabloid (that was once a failing but respectable paper). However, we’re told upfront who the killer is, and why. It’s a bit Columbo that way. I doubt it was a very direct influence, but I wouldn’t be surprised to learn Westlake read Fuller’s book. The movie was a rarity on TV in the Pre-TCM era.

And of course there’s a romance between rival reporters. Donna Reed dirties up nicely, but she’s no Sara Joslyn. She still wants to play by the old school rules. Still, worthy of mention.