I wage not any feud with Death

For changes wrought on form and face;

No lower life that earth’s embrace

May breed with him, can fright my faith.Eternal process moving on,

From state to state the spirit walks;

And these are but the shatter’d stalks,

Or ruin’d chrysalis of one.Nor blame I Death, because he bare

The use of virtue out of earth:

I know transplanted human worth

Will bloom to profit, otherwhere.For this alone on Death I wreak

The wrath that garners in my heart;

He put our lives so far apart

We cannot hear each other speak.From In Memoriam A.H.H., by Alfred Lord Tennyson

Every era, and every nation, has its own characteristic morality, its own code of ethics, depending on what the people think is important. There have been times and places when honor was considered the most sacred of qualities, and times and places that gave every concern to grace. The Age of Reason promoted reason to be the highest of values, and some peoples–the Italians, the Irish–have always felt that feeling, emotion, sentiment was the most important. In the early days of America, the work ethic was our greatest expression of morality, and then for a while property values were valued above everything else, but there’s been another more recent change. Today, our moral code is based on the idea that the end justifies the means.

There was a time when that was considered improper, the end justifying the means, but that time is over. We not only believe it, we say it. Our government leaders always defend their actions on the basis of their goals. And every single CEO who has commented in public on the blizzard of downsizings sweeping America has explained himself with some variant on the same idea: The end justifies the means.

The end of what I’m doing, the purpose, the goal, is good, clearly good. I want to take care of my family; I want to be a productive part of my society; I want to put my skills to use; I want to work and pay my own way and not be a burden to the taxpayers. The means to that end has been difficult, but I’ve kept my eye on the goal, the purpose. The end justifies the means. Like the CEOs, I have nothing to feel sorry for.

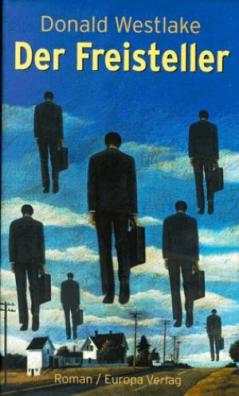

This was certainly Westlake’s best-reviewed novel, to the point where (as I mentioned already) it was starting to worry him, as he learned how much higher the bar had been set for anything he wrote subsequently. But for all of that, we shouldn’t kid ourselves. It was still a novel from a genre writer, a mystery writer, a writer best known for comic hardcovers and hardboiled paperbacks; a writer who never had a real bestseller (though this came close), or won a mainstream award. A writer who published so many books, mainly geared to popular tastes, that no one of them, no matter how superb, could ever be treated as some epochal literary event, even though arguably no work of literature ever summed up its epoch more perfectly than The Ax.

There was and is no review in The New Yorker. There was and is no review in The New York Review of Books. There was and is no review in the Times Literary Supplement (which did review his Up Your Banners very favorably, if also briefly and anonymously–and with a certain sense of disorientation, since the reviewer didn’t understand how such a novelist so adept at dealing with social issues could be wasting his time on thrillers). There was and is no review in Harpers Weekly. And etc. This book did not elevate Donald E. Westlake to the rank of Literary Lion, and given how mixed his feelings clearly were about that lofty league of sacred scribblers, that’s perhaps just as well.

The newspaper reviews were many and glowing, and it was mentioned by many critics in their end-of-year Noteworthy Books pieces–this was, after all, a very topical story, and it got more and more topical as time passed, so reviews have continued to appear, as the book has been rediscovered with each new downturn, each new swing of The Ax, each new angry outburst from a struggling and aggrieved Middle Class. Even the film Costa-Gavras made almost a decade later constitutes a rediscovery. People keep saying this book is a timeless classic waiting to be acclaimed as such. I expect they’ll be saying that for some years to come.

I’m merely adding my mote to the pile here, giving this book some of the more intensive study and analysis it merits, while still believing that anybody with a brain and a heart can understand it quite well without my prattling pontifications. The fine details, the little half-hidden jokes he loved to stick in for lagniappe, even in his more serious stuff, may be missed by many (probably no one would be sharp enough to spot them all), but they are not at all the point of the endeavor. They are there for those who can appreciate them. If not on the first reading, perhaps years later, when the reader has become more seasoned, read more, picked up a few more scars on the battlefield.

If this is not universally recognized as a Great Book (you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone calling it a bad one), it may be only because it’s too accessible. Its truths are too universal. (See all those covers up top? More where that came from, I bet.) Its style is too meat and potatoes, as is its protagonist, and its theme. There are ambiguities in it, identity puzzles, moral shadings that could (and should) be debated at length. But the stark outlines of the story’s meaning (and stark would be the adjective to use) are not ambiguous, not ambivalent, not encoded. They are there for all to see.

Which to be sure is equally true of many a universally acclaimed masterwork, from before the postmodern era (shall we ever get to the post-postmodern era?). Westlake is, I sometimes think, the greatest 19th century American writer who ever got born into the 20th (and I think he knew it, too). But while his sensibilities may be at times archaic, his keen perceptions remain fully trained on the present. He doesn’t write in the past, even when he’s gazing longingly back at it. He’s a Miniver Cheevy who has learned, painfully but willingly, to live in his own time.

Which means, of course, living in a succession of times, a tumult of overlapping eras, amidst a sea of people who don’t understand each other, for reasons of race, religion, politics, culture, history, generation, temperament, and language. We can hear each other speak, perhaps–no end of mediums for hasty ill-thought self-expression–but how often do we ever comprehend what is being expressed before it’s too late?

So in this book Westlake concentrates on just one quiet focused voice within the tumult–a man who says very little out loud, who has never really been good at sharing his feelings, his thoughts. He has much of value to say, but no one to say it to in his daily life. His wife would listen, wants to listen, but because she’s never had a career, never been the provider in the family (his choice, much more than hers), she can’t know what it means to lose all that. His children are caught up in the questions of their own lives, as adulthood draws near for them. Needing to find out who they are, they can’t stop and notice the changes in their dad (dads aren’t supposed to change).

His friendships all stemmed from his job–and in a rare moment of honest eloquence at a counseling session, he says that as soon as he and his co-workers at the paper mill were laid off, they became each others’ competition–they became the enemy. His enemies. And what do you do with your enemies? You kill them. In a well-ordered society, only metaphorically. But Burke Devore has moved beyond the metaphorical. And he can’t allow anyone to know that. Anyone but us.

So he goes out on job interviews (sometimes even real ones), but with the secret purpose of seeking out and terminating six men, who have already been terminated in the professional sense, just like him. First the metaphorical ax, then the real one. Each of them is guilty of being better-qualified, if only slightly, for the position he intends to create for himself at a nearby paper mill, by murdering the man who currently holds it. Of the seven he needs to kill, he’s done for three (the hysterical wife of the second was collateral damage, regrettable but necessary). Four to go.

But Life won’t make it easy on him, keeps distracting him. He doesn’t simply want his job back, he wants the life that came with it, and his family is an integral part of that life. His children will leave home soon (maybe not as soon as he thinks, that being another social change in the offing), but his wife Marjorie is necessary to him, and she finally breaks through the wall of his concentration to let him know she’s been having an affair with a neighbor, and she wants them to get marriage counseling. Communication between them has broken down. She wants him to share more, so she can help him with what he’s going through. Well, she thinks that’s what she wants.

His reaction is threefold. First–they can’t afford counseling (this is the reaction he shares with Marjorie, who remains adamant). Second–he can’t afford to open up to anyone about what he’s going through now. Third–he’s going to find out who the lover is and kill him. He knows how. His skill set is getting larger all the time. But what’s the point, if Marjorie leaves? He has no choice but to agree to counseling. He’ll keep his own counsel about the things that matter, and he’ll pick up the pace on his project–once he’s got his job, the right job, the problems in his marriage will be solved.

And next on his list is Kane B. Asche, 11 Footbridge Road, Dyer’s Eddy, CT. The man’s resumé perhaps imprudently mentions he is still under 50, which just makes Burke that much more determined to kill him. He tells us that he’s gone out of his way to learn his victims’ middle names, via their birth certificates–not because it assists him in any way, but because it gives him a sense of power over them, knowing their secret name, the one they hide behind an initial. He says he’s noticed the police always use the middle name when they announce a manhunt or arrest, so they feel that same sense of power.

Dyer’s Eddy is a whirlpool that occurs at a point in the Pocochaug River, and the footbridge in Footbridge Rd. goes right over it, and this is all made up, there is no such river, there is no Dyer’s Eddy (at least not by that name), but I feel terrible saying so, because you absolutely believe there is such a place when you’re reading Burke’s description of it. Westlake blends real and ersatz place names and geography so skillfully here, you have a hard time knowing where one leaves off and the other begins, unless you know the area in question very well indeed; which somehow only adds to the strange pleasure of reading this book, which I suppose is akin to Burke’s pleasure in knowing his victims’ middle names. (Not that I know Connecticut well at all–I get this little added thrill a bit later on.)

KBA, as Burke refers to him, has not been unemployed long, and seems to be childless, which Burke figures is the reason he and his wife are still so very close and cozy with each other, working on a vegetable garden together as he watches them–thrifty, therapeutic, and romantic. He can’t stand it. Can’t wait to kill this guy, but not while the wife is there–can’t go through that again. He’ll come back later to finish the job. Now he’s got to go to counseling.

The counselor’s name is Longus Quinlan, and Burke can’t figure out how anybody gets a name like that, until they meet him, and he’s black. Burke isn’t particularly racist, but he’s clearly had little contact with anyone who isn’t white, and that can amount to the same thing. He tells us earlier that he just assumes anybody who gets a job in his field who is a minority–or female–got it because of affirmative action. He doesn’t even consider them real competition.

So he takes Mr. Quinlan rather lightly at first, but learns over time that he’s wrong to do that, and he adjusts his conceptions accordingly. He can’t afford the luxury of blind prejudice. He can’t afford to underestimate anyone. But knowing little about what a counselor does, and having been on the taciturn uncommunicative side even before he became a murderer, some hostility is bound to surface.

He held up a hand and raised a finger and smiled past it at us. “We don’t yet know what it is you want,” he said. “You think you know what you want. What you probably think is, what you want is what you used to have. But it may turn out, that isn’t what you want, after all. That’s one of the things we’ll have to discover along the way.”

What he’s saying, I realized, is that we may wind up ending the marriage when this is all over, and then that’ll turn out to have been what we wanted all along, and he’ll have turned out to have done his job. Pretty good. How do I get into this line of work?

(Given what happened to an equally affable and perceptive therapist in The Stepfather, Mr. Quinlan should feel most fortunate if he gets out of this book alive, but Burke differs in many crucial ways from ‘Jerry Blake’–no doubt they’d have an interesting conversation, those two. Before one killed the other. My money’s on Burke.)

The morning he goes back to Dyer’s Eddy, Burke gets a late start, he informs us, because he had trouble sleeping the night before. He had a minor epiphany that woke him up–when Marjorie told him about her boyfriend, his immediate reaction was not enraged jealousy, but cold-blooded determination. This man is threatening his marriage, so this man will die. He realizes that because he’s made murder the answer to his employment woes, he’s starting to think of it as the answer to everything.

I’m not a killer. I’m not a murderer, I never was, I don’t want to be such a thing, soulless and ruthless and empty. That’s not me. Whatever I’m doing now I was forced into by the logic of events; the shareholders’ logic, and the logic of the marketplace, and the logic of the workforce, and the logic of the millennium, and finally by my own logic.

Show me an alternative, and I’ll take it. What I’m doing now is horrible, difficult, frightening, but I have to do it to save my own life.

If I kill the boyfriend, it will be something else. Not exactly casual, but normal. As though killing has become a normal response for me, one of the ways I deal with a problem. Simple; I murder a human being.

The untroubled ease with which I’d thought that thought–kill him, why not–is what’s frightening, what scares me. I’m harboring an armed and dangerous man, a merciless killer, a monster, and he’s inside me.

And he assumes that somehow, if he can finish his quest, get the job, this change in him will “bleach away, like the most recent fat melting off when you first go on a diet.” He has to get rid of the killer inside him, and the only way to do that is to kill faster, so this time he’s not going to hesitate, even if he has to kill the wife as well–if they insist on being the most tight-knit couple alive, always together, he can arrange for them to stay that way forever.

But he doesn’t. He figures out KBA is working at a local nursery (that’s how he can afford all the gardening supplies), and he finds him alone there, and out comes the Luger. Two resumés to go, then he creates a vacancy for himself, a new life to replace the one taken from him. He doesn’t even seem to imagine the wife’s reaction when she learns her life is gone. He doesn’t ask himself if it would have been more merciful had he taken them both out. He leaves that to us.

And he gets all sociological on us again, and it’s pretty good sociology (you keep thinking somehow that the paper industry was not such a good fit for him, but maybe he was a late bloomer, intellectually speaking). He’s got something to say about the middle class. Well honestly, these days, who doesn’t?

We were supposed to be protected and safe, here in the middle, and something’s gone wrong. When a poor person loses some lousy little job that had no future anyway, and has to go back on welfare, that’s an expected part of life. When a millionaire shoots the works on a new venture that falls flat and all of a sudden he’s broke, he knew all along that was a possibility. But when we slip back, just for a little bit, and it goes on for month after month, and it goes on for year after year, and maybe we’re never going to get back to that particular level of solvency and protection and self-esteem we used to enjoy, it throws us. It throws us.

And what happens is, because we’re family people, it’s throwing the families, too. Children turn bad, in a number of ways. (Thank God we don’t have that problem.) Marriages end.

Burke is making several bad assumptions here (including the notion that the rich foot the bill for their failures in present-day America), but the one that hits closest to home comes in the form of a phone call in the middle of the night, that Marjorie gets, because, Burke sourly notes, he’s not really the head of the household anymore. But that’s about to change.

His son Billy has been arrested for robbing a small computer store with a friend. Burke’s immediate instinctive reaction is to say “It’s my fault” and to do everything in his power to shield Billy from the consequences of his crime. When they see him at the State Police headquarters, Burke lets Billy know that he must say this was his first and only offense and stick to that story no matter what. Burke already knows that isn’t true, Billy has done this multiple times. He’s telling his son to lie to the police, and to lie consistently.

A lawyer is obtained–they can’t afford the best legal talent, but they get an older semi-retired attorney with the right experience and connections. Billy’s case is detached from that of his friend–who was found to have a large amount of stolen goods in his home. None was found at the Devore home. Burke anticipated the police searching the house, swept it clean of all incriminating evidence (and hid the Luger he’s used to murder four people under the seat of his Plymouth Voyager.) Billy’s friend would have a better chance of avoiding jail if he and Billy were tried together–but more likely he’d drag Billy down with him. So the entreating glances of his terrified parents are studiously avoided by both Burke and Marjorie.

Burke tells us that a short time before, he’d have trusted the police, and the prosecutors, and the courts to do the right thing, to protect him and his family–and now he knows you can’t trust anyone, that all the system wants to do is chew his boy up, and spit him out, and that it’s his job to protect Billy from that. He looks at the fairly professional state cops, who are not being abusive, who are doing their jobs more or less correctly (Billy is local, white, still marginally middle class)–and he sees hated implacable enemies to be defeated. He no longer believes in society, in law and order, in good government. There’s you and your family, and nothing else.

And both Billy and Marjorie respond to his strength, his certainty, and do what he says with little or no hesitation, circling the wagons. What the daughter, Betsy, thinks of all this is unknown (that would have been an interesting companion piece to this novel–perhaps a novella written from her POV–oh well).

Billy avoids jail, and his record is sealed, meaning that if he has no further offenses, he’ll have no criminal record. Burke has saved his boy, and furthermore has told him, with great kindness and understanding, that it was just a mistake, they’ll get past it, everything will be fine–he’s become a hero to his son, and of course to his son’s mother–who quietly tells Burke that she’s ended the affair. Burke has already figured out who the boyfriend was–a downsized former bank executive, now working at a Mercedes-Benz dealership, selling expensive toys to his former peers, maybe even to former colleagues. Burke’s sorry for the man. He can afford to be. No competition for him now, on any level.

And when this book came out, absolutely nobody wrote about how this was drawn from an episode from Westlake’s own youth, how he’d been the boy hauled in by the State Police for theft, how Westlake’s father Albert had fought with everything he had to make sure his son’s life wasn’t destroyed, and how he’d said that it was his own fault this had happened, because he hadn’t been successful enough in life to give his children the things they deserved. The few who knew about it were not in a position to talk about it. And even with a bonafide masterwork to his credit, Westlake wasn’t the kind of writer who got that kind of scrutiny. (But you can’t say he didn’t give the critics plenty of hints.)

That grief, that guilt, that gratitude, had lain inside Donald Westlake for decades, expressing itself in various oblique ways in his storytelling, but now he was ready to tackle it all head-on–and I know–I know–that he wept quietly when he wrote parts of this. And now you can read about that episode in a fragment of his unpublished biography in The Getaway Car, and wonder to yourself how many other things we’d learn about him if it ever got published. The scene rings true whether you know what’s behind it or not. But it’s good to know.

And you still wonder–was Westlake saying that his father should have just let him get ground up in the mill, teach him a lesson? Impossible to believe. No, he was saying that even at its best, the criminal justice system is so geared towards retribution that it can destroy lives for no reason at all–Westlake had stolen a microscope and pawned it. How many kids have gone down with barely a ripple because of stupid youthful mistakes like that? He was one of the lucky ones. And he knew it. Survivor’s guilt, turned to anger at the way things are. And the creeping awareness of just how much worse they could become, if we aren’t careful.

But if he’s making this multiple murderer the bearer of this message, that means we can’t just dismiss Burke Devore as a monster, a freak, a ‘serial killer’–he’s none of these things. Within the painfully narrow moral context he’s occupying now, he’s right. He’s seeing things as they really are. But how well is he seeing himself?

He can’t stop to think about that. He moves on to his penultimate resumé, but he has a wonderful bit of luck, before he has time to strike–a call to the house leads to a revelation from the man’s wife–he’s gotten a job! A job Burke himself interviewed for, involving soup can labels, that he didn’t get. For a moment, Burke is gripped with rage, thinking it’s the Arcadia job (which of course it couldn’t be, since Burke hasn’t killed the current holder of that job yet), but then realizing his mistake, he’s filled with joy and relief. He tells the mystified wife how truly happy he is for both of them (he really is, and without the slightest tinge of irony). He scratches the lucky fellow off his list, and thinks of them no more. Just one more resumé to go now.

(I would be remiss not to mention that in scouting out this house, on a walking trail behind it, Burke heard the wife coming up behind him, hitting trees with her stick, to ward off snakes. See how well it works?)

This book plays no structural games, of the type Westlake often indulged in. 47 chapters, 273 pages in the first edition. I suppose the 47 could be a reference to Black ’47, the height of the Irish famine–but it’s a different Celtic catastrophe that gets referenced in Chapter 24. The Highland Clearances, which Burke says he read about in college. He liked history, did well in it. He thought of what he read in the history books as just stories. He knows better now.

The Highlanders thought they were on their own land, that they had something that couldn’t be taken away from them, as long as they worked hard and followed the rules set down by their society. But then the landlords, good Scotsmen themselves for the most part, realized that if they cleared the land and turned it over to sheep, they’d make more money than they ever could from rents. So they just turned the people off their little plots of land, burned the houses, knocked down the fences, brought in the sheep, and the people had to find somewhere else to go. Or else they had to die. And many of them did just that.

And it’s an old old story, lads and lassies, that’s been told in every language ever spoken, though some versions are sadder than others. And Burke tells it well here, but I’d say these fellows are a bit closer to the source.

But here’s what Burke has to tell us–it’s not just a story. It’s not just the Highlands of Scotland. And it’s not just the past. Well, Faulkner could have told him that. Or the present-day residents of Balmedie, Scotland, down by the sea. They’ve got a new golf course now, did you hear? Look it up.

It’s the descendants of those landlords that are doing the clearances called downsizing now. The literal descendants sometimes, and the spiritual descendants always.

You like that desk where you are? You say you’ve given the company your life, your loyalty, your best efforts, and you think the company owes you something in return? You say all you really want is to stay at your desk?

Well, it isn’t your desk. Clear it. The owner has realized he can make more money if he replaces you with another sheep.

So a variety of things happen before the next body drops. Burke gets a visit from a police detective, who tells him that he’s investigating a link between two of Burke’s victims. They both interviewed for the same job, and they both were shot with the same gun. It’s pretty clear Burke isn’t a suspect, at least not yet–the detective is just wondering if Burke knew either man, and Burke says he didn’t (he expresses some concern about whether he might be next, and this is a nice ruse, but in fact he does tell us he’s getting nervous going out to get his mail lately–suppose somebody else had the same idea as him?).

The detective leaves, still baffled, and Burke knows now he can’t use the Luger anymore, nor can he get another gun. And the great thing about guns, he says, is the way they distance you from killing. Make it more of an abstract thing. He’s not sure he can strangle or stab anybody.

Yes, there are criminal byways he could use to obtain a sidearm illicitly–but he doesn’t belong in that world, he thinks to himself–he’d be destroyed there. He’s no criminal. He thinks about how if he’d killed Garrett Blackstone, the man who got the job making soup can labels and disappeared from Burke’s list (like magic!), the police would have known for sure it was no coincidence. He’s going to have to find other methods to employ in order to finish his project. He’s going to have to keep upgrading his skills. And he’s going to have to find a way to get at his final resumé.

Hauck C. Exman, of 27 River Road, Sable Jetty, NY. A former marine, who worked for the same company all his life after leaving the military. It seems he has retained the military mindset. His riverfront home, Burke notes with disgust, is in a strategically sound location, with all the advantages of terrain, and it would be impossible for him to sneak up on the guy there. It’s alongside Route 9, atop the Palisades, by the banks of the Hudson (a lovely road to drive, if you’re ever in the area). Mr. Exman has several exes, it seems, and the current one is mowing his lawn, as Burke surveys the battlefield, and leaves feeling most discomfited. This is going to be a tough nut to crack, particularly without the artillery.

But before he makes his play, he’s got to get through another session with Marjorie and Longus Quinlan, and for just a moment there, his certainty in the rightness of what he’s doing is compromised, ever so slightly.

Quinlan is trying to reach Burke–he doesn’t quite know why he finds this man so troubling, but he knows there’s something there, something more than just a couple having communication problems, and he rightly assumes it’s about losing a job, so he says the usual thing about how some people take that as an opportunity, and Burke’s heard that before, says it’s crap.

Marjorie looked at me, startled, when I said that, when I told Quinlan he was saying crap, because we’d all been gentle and polite with one another up to now, but Quinlan didn’t mind. I’m sure he’s heard a lot worse in that office. He grinned at me and shook his head and said, “Mr. Devore, what you’re picking up as the message is crap, I’ll go along with that. But what you’re picking up is not what I’m sending out, and it’s not what those people at the mill were sending out. The real message is, you are not the job.

I looked at him. Was that supposed to mean something?

He saw that I still wasn’t receiving whatever it was he was trying to send, so he said, “A lot of people, Mr. Devore, identify themselves with their jobs, as though the person and the job were one and the same. When they lose the job, they lose a sense of themselves, they lose a sense of worth, of being valuable people. They think they’re nothing anymore.”

“That isn’t me,” I said. “That isn’t the way I look at it.”

He’s lying. He believes the lie, and he tells it convincingly, and he’s right to be angry about all the self-help bullshit they fed him on the way out the door, but he’s lying, and we know he’s lying, because we’ve been inside his head listening to him all this time, and what Quinlan just described is exactly what he’s been expressing to us, but he’s forgotten it. This isn’t a diary we’re reading, it’s a chain of thought, and it keeps getting further and further away from its point of origin.

The man who could have listened to what Quinlan has to tell him is dead, replaced by a man who probably does no longer think of himself as the job–who knows the job can’t be him, because no job belongs to you, because nothing belongs to you, except your skills and your mind and your determination to make a place for yourself in a harsh Darwinian world that is always trying to destroy you and your family. A few months ago, these words might have given him pause, might have kept him from starting down the road he’s on. But having gone so far down it already, it’s too late for him to turn back. So he goes back to Sable Jetty to finish what he started.

He can’t figure out where Exman is going. It’s a bad place to do surveillance, he can’t just wait outside all day. Some kind of weird schedule the man is keeping. He has to lure him out of that fortress, somehow. And he comes up with a really mean trick, and he’s ashamed of pulling it, and worried it might backfire, but in the event, it works beautifully.

He sends Hauck Exman a letter, from that fictional company with the fictional ad about a fictional job opening that got him all those resumés to start with, telling him that the person they hired has turned out to be unsatisfactory, that they now realize they were mistaken not to have hired Hauck Exman to start with, and they’d like to interview him–secretly, away from the office, so as not to create an unpleasant scene with the man currently on the job, who they are going to dismiss as soon as they have his replacement.

Burke’s judged his man well–his vanity, his arrogance, his desire to be interviewed by a fictional Personnel Director named Laurie Kilpatrick who he will naturally assume is young and attractive and eager to flirt with him. Burke even fixes it so that Exman will send back the letter to Burke’s P.O. box with his answer to the interview request (to avoid an embarrassing phone call that would alert the man he’s going to replace)–hopefully eliminating any chance of a trail leading back to him.

So the meeting is to be at an expensive restaurant, and of course that bitch Kilpatrick never shows, since she doesn’t exist and all. Exman waits for hours, and finally leaves, looking small and defeated (and surprisingly well-dressed, Burke notes from his lookout post). He follows him back to Sable Jetty, only to see him drive to a mall–he’s a salesman at a men’s clothing outlet there. That’s how he can afford the nice suit. But pretty soon, he’s not gonna like the way he looks. Burke guarantees it.

He has to chat him up a bit, but that doesn’t bother him anymore, as it did with previous targets. He’s getting better and better at improvising plans of attack in the field. Having figured out when his victim will be leaving work, and knowing where his car is parked, Burke heads off to do some shopping. As he tells us, “If you want to kill somebody, you can find everything you need for the job down at the mall.” Now who does that remind me of?

By closing time, he’s got the hardware, and the former marine walks right into his trap. Civilian life makes you careless. You get used to people not trying to kill you after a while. Burke pretends to be having car trouble–he’s already told Exman that he’s in the market for a sport jacket, and now the guy figures he’s out a commission if Burke has to call a mechanic in, so ever the man-in-charge, he leans over to take a look under the hood, and gets two quick blows to the head from a hammer. There’s a tarp all ready for him in the cargo area of the Voyager. It’s after dark, it’s one of those huge mall parking lots, everybody’s wrapped up in their own lives–nobody notices a thing.

It’s too late for him to dispose of the body, so he stores it in a leaf bag in his garage. A few steps away from his wife and children. The next day he takes it to the recycling center (he can’t afford home garbage pick-up anymore). Hauck Exman’s trussed up body, encased in sturdy plastic, will end up in a landfill, out on the Long Island Sound. Well, at least he’s biodegradable.

And Burke realizes he’s having a hard time remembering the name of the first man he killed–Herbert C. Everly, that’s it. Both his first and last resumés had the initials HCE. Which may in fact be a reference to Finnegan’s Wake (so much good stuff I missed entirely has come up in the comments section for Part 1), or to something else entirely, or to nothing at all (I don’t really believe that), but to Burke all it means is that he’s getting better at this sideline of his.

How simple that one was, simple and smooth and fast and clean. It encouraged me, it made everything else possible, because it made me believe the whoel thing could be that impeccable. If I’d had the second HCE to do first, none of this would ever have happened. I just wouldn’t have been up to it.

The idea of the learning curve is, the first time you do something you aren’t very good at it, but you learn something about how the job is done. Then the second time, you’re better, but still flawed, and you learn a little more. And so on, until you’re perfect. The learning curve is an arc, beginning with a steep upward sweep, because you’re learning a lot each time in the early days, and then gradually it flattens out to a level, as you learn in smaller and smaller increments the nearer you get to your ideal.

And he tells himself that it’s ironic that just as he becomes perfect at this new job, he won’t be doing it anymore, but then he thinks you never know–it can be a useful skill.

He’s already sent out a batch of fresh resumés, including one to the mill in Arcadia, so now it’s time to create a vacancy there. It’s time to go see Upton ‘Ralph’ Fallon. URF. He lives in an isolated old farmhouse, which Burke is pleased to note does not have a resident dog to give the alarm. He breaks in without much trouble–the main entrance hasn’t been used in years, and isn’t locked, just jammed. He forces it open. The place is empty. He’s got some time to do homework. He knows now it’s best to learn things about a person before you kill him.

The first time is a wash–Ralph brought a woman back with him, somebody he picked up in a bar. Burke leaves quietly, and tells us he’s not the least bit discouraged. He’s putting another plan together. Using what he finds to hand. He doesn’t need the Luger anymore. It would be a hindrance to him.

So he’s waiting there, a few days later, but the man does love to stay out drinking (as divorced men with child support to pay often do). Burke knows he has to do this when Fallon is alone, and before his two young children come to visit. But he’s getting a bit too comfortable in his new self–he falls asleep, and wakes to find his victim glaring at him, a gun in his hand.

Well, seasoned professionals don’t panic at the unexpected. Burke talks to him, tells him his true name and former occupation–he’s a fellow polymer paper man, he lost his job, he’s come to get his advice on how to find a new one. His sympathies engaged, and his nervous system still lulled by a surfeit of alcohol, Fallon drops his guard. Puts down his gun. Picks up the booze, and they talk shop. Eventually falls to sleep himself.

Now here’s a chance for a merciful hit. Burke can kill this one without his ever knowing about it. That’s what you’d expect him to do. But he can’t. This one has to be perfect. He needs it to look like an accident. So he duct tapes him to the chair he’s snoring his last moments of life away on, and then duct tapes his mouth shut. That wakes him up, but the second length of tape, over his nostrils, puts him to sleep forever. But not instantly. And not without pain and distress and fear and involuntary vomiting, and he drowns in his vomit. It just can’t be helped, is all. He has a job Burke needs, and Burke has to let him go. He removes the duct tape. He removes all the fingerprints he can find (like the police in a burg like that would even look for them).

The house has a gas stove. It has propane tanks. And it has candles. Burke is using only what’s there, nothing he brought with him. As he drives away, he hears an explosion–the whole countryside will hear it. And will assume that drunken bum finally did himself in, won himself a Darwin Award. The Perfect Murder. It does happen, bet on it. Only the failed attempts at it ever make the papers.

And as he and Marjorie get back from a counseling session he paid absolutely no attention to while it was going on, Burke gets a call. Guess what? He’s got an interview at Arcadia Processing.

But then he’s got an interview at his house, with that same detective again, named Burton, and why would he be back again? What does he know now that he didn’t before? Burke has a moment of panic–this is the moment when many a man would run, but Burke isn’t that kind of man anymore. He steels himself, faces the cop calmly, telling himself it’s just procedure. And that’s exactly what it is. This isn’t one of those stories, you see, where we get to follow the daring criminal all through his evil scheme, secretly reveling in his prowess and cunning, but then we see him taken off by the law at the end, so we can say “See, I was never really identifying with him. I wanted that to happen all the time. Bad guys need to be punished at the end.” Think so, do you? Then how come you’re reading a Donald Westlake novel?

It’s almost too good. Burton’s only back to give Burke a bit of closure (nice of him). See, Hauck Exman interviewed for that job the other two dead men (and Burke) interviewed for. And the good detective interviewed Mr. Exman, and Burke can just see it–how unhelpful and irritable and offputting Exman would have been, how dare you waste my time with this, what are you implying here? And then he disappeared. Like from the face of the earth, even. That woman at the house was his fourth wife, and she’d found out he was playing around, and she’d filed for divorce. And his house was full of guns. Obviously he got rid of the one he used as the murder weapon. Case. Closed. Another thrilling mystery solved by the amazing Detective Burton! Tune in next week when–oh never mind.

Burton sees Burke is wearing a tie–Burke tells him he’s got a job interview, and this time he thinks it’s going to work out fine. Burton wishes him luck. Some people make their own luck, you know. Not necessarily good people.

The first time I read this ending, I must confess to all of you now, I read into it–I felt like Burke was somehow disappointed that the law didn’t catch him, that there really is no justice in this world, that God isn’t watching (or else he’s watching, but he’s on Burke’s team, which would be a forgivable conclusion for Burke to come to, seeing how things have worked out). I can’t fool myself about that anymore. Burke might have felt that way a short while before, but now he’s just relieved and happy and pleased with himself, and looking forward to getting back to making paper. He has no regrets at all.

And he’s looking forward to not having to commit any more murders, but there’s a qualifier comes with that. He won’t kill anyone again, unless somebody makes him. Unless somebody else threatens his job. Because after all, nothing is forever. Change is perpetual, in all industries, all walks of life. The mill is doing fine now, but could be some spiritual descendant of those Scottish landlords will get some bright idea about new efficiencies, new redundancies, more money for the stockholders, a bright new feather in his cap. Burke will be watching closely for that. And if it happens, he’ll know what to do, and who to do it to. And he’ll know how to do it, so that no one will suspect. The Ax can fall in more than one direction now.

And on one level, his creator–the God of his universe–is horrified by him. By the vacuum that his soul has become. By the way he has let himself completely become his job–both his jobs. There isn’t a whole human being there anymore, nor will there ever be again. He could have chosen to know himself better, and he finally chose not to know himself at all. Burke Devore is a killer who refuses to think of himself as a killer, even as he thinks about potential future killings.

So why does he walk away clean? Because the Great God Westlake plays it fair, right down the line. Burke Devore may refuse to know himself, but he knows the world he lives in. He’s correctly perceived the rules it now operates by. He looks us right in the eye, and in the end, we’re forced to look away, trembling slightly.

And say this much, he didn’t turn to someone else to solve his problems, and he saw who his enemy was, very clearly indeed. He didn’t blame the blacks, the gays, the immigrants, the Jews, the Muslims, the government, the lamestream media. He didn’t put his faith in some slimy huckster, nor did he call out to some partisan deity to save him, while damning everyone else.

You can be a part of society, and live by its rules, its moralities, trusting in a flawed system that has, nonetheless, given us a level of peace and prosperity that our ancestors would have envied. Or you can be an army of one, and live for yourself, seeking no quarter, and giving none, and not allow yourself the luxury of pretty lies. Those are your choices. Burke made his. We still have to make ours. Knowing all the while, as an earlier Westlake protagonist who made very different choices once said, that it’s truly exhausting, having to spend your existence slowly circling your fellow man, your hand on the hilt of your knife. Or your Luger. Well, it’d be a Glock now. Lugers look nice, but they’re not practical.

But now we have to think about yet another protagonist–not Westlake’s, exactly. In the same family. Different genus. He’s stirring now, after a long sleep. I think maybe Burke woke him up. I can see him coming, across the George Washington Bridge, his hands swinging at his sides, his onyx eyes impossible to read, but I can guess what he’s thinking. “You people always make a mess of things. You’re all crazy. I’m the only sane one there is.” He’s got a point. And a Smith & Wesson Terrier. And business to attend to.

And we need him now, strange it it may sound. We need him to teach us what he knows. How to see beneath the surface of things, of people trying to destroy us, no matter how much we don’t want to. How to learn from the past without becoming trapped in it. How to find the strength to fight back, against malevolence, mendacity, and mob-think. We need him to teach us about dishes best served cold. We need him, and here he is, at last. Like a bad penny. Good to see you, Parker. Where you been?

And there’s nothing he can say to that, so he says nothing. We’ll have to listen more closely. Learn by emulation. To the limited extent we poor gibbering apes are able. If a wolf could speak, we would not understand him. This one has an interpreter, though.

Where has he been? And more relevantly, when? We’ll talk about that next time. But for the sake of argument, let’s say it’s 1982. The Planet Saturn.

(Part of Friday’s Forgotten Books)

Thank you again for your fine thoughts on this, my favorite Westlake novel. The Billy-gets-arrested sequence may be my favorite sequence in the book. (I sometimes re-read just that section.) Burke’s previous (morally abhorrent) actions inform his actions here, but in this case, it’s hard to find much fault with his actions. It may not be legal or moral, but for Billy and his family, it’s arguably the best choice. Would Billy be better off in life with a juvenile record? No, he would not. And there’s little doubt Billy won’t re-offend.

I wonder about Detective Burton returning to Burke’s home. Is it just to offer closure, or does Burton suspect Burke of something? It’s hard to imagine a busy homicide detective taking time out of his day to visit a tangential, irrelevant witness to give him to give him an update on the case. Is this Westlake taking liberties with reality to sew up the plot or is he planting seeds of doubt? Personally, I think Burton smells something, he’s not sure what, on Burke, and he’s keeping an eye on him to see what shakes loose. Doesn’t mean Burke’s going to be caught, but he’s attracted attention. He’s not quite as self-contained as he believes.

Another seed of doubt: The message from Arcadia indicating that because Burke wasn’t home, they’ve set up some other interviews. Maybe Burke doesn’t have this sewn up. He’s pretty confident as the novel ends, but the novel doesn’t end with him getting the job. It ends on a note of hope, seasoned with (overlooked by its protagonist) doubt.

Billy won’t re-offend, because Westlake didn’t. Maybe he’ll write about crime, someday. Maybe he’ll start looking at old murders around where he grew up, for background research. Maybe he’ll find some things in his father’s trunk that pique his curiosity. But then again, maybe the absent Betsy is the real source of concern here–or maybe the one who has to worry is the guy who knocks her up. Westlake did not choose that name on a whim.

Westlake’s interview comments subsequent to this book coming out don’t give much indication of any great ambiguity about the ending. Nor does his general attitude towards police and detectives. Nor does his overall body of work to date. I think Burke got away with it, and I think he got the job–one way or another. Whether it turns out to be everything he hoped for–that’s something else again. I think, as with Art Dodge at the end of Two Much, his punishment is the loss of his true self. But the thing is, once you’ve sold your soul, you don’t miss it. Maybe it misses you.

You think you know what you want. What you probably think is, what you want is what you used to have. But it may turn out, that isn’t what you want, after all.

That’s about the job as much as the marriage, of course. It’s another message Devore dismisses as crap, but Quinlan is a pretty smart guy. Middle management jobs are frustrating; you often have more responsibility than power, and your careful, painstaking plans can be destroyed instantly at the whim of the people above you. Devore is not the organization man he used to be; he’s a loner who takes matters into his own hands. So …

Yeah. We can assume that he gets what he thinks he wanted, but will he be content with that? That’s a whole different question. And having decided to take arms against a sea of troubles and in opposing end them–he can’t just let things go anymore. And you do have to do that sometimes. Some things you have to let go. He let Marjorie’s affair go, to be sure. He won’t kill people just for offending him in some way. He won’t make murder the answer to everything. But that tool will be lying there in the kit, and he won’t just leave it there the rest of his life. Some things he won’t be able to let go. He enjoyed that sense of power over people, much as it scared him. Running a polymer paper production line isn’t going to give him that same high.

And what happens when he meets another loner who takes matters into his own hands? He’s not the only one, we can be sure, and he’s aware of that. He got out ahead of the curve, maybe–an early adopter. But there’ll be more. More ax men. And ax women.

There’s a certain power in living in a society that runs by certain rules, certain assumptions, and to know you are not bound by those rules, those assumptions–that you have a freedom of movement that most people don’t have. But the more people who live like that, the weaker the advantage becomes. The truth is, if you’re like Burke Devore–or Parker–you don’t want most people to agree with you. Not if you’re smart. You want things to go on as they were, with most people toeing the line. If it all falls apart, goes full Darwin, then you’re just another asshole, and there’s always a bigger asshole waiting in the wings. The Ax will fall on you, because the Ax plays no favorites.

I think it was a novel of ideas, and it failed at that. Westlake had this sketch, a skeleton of the idea, and he tried to flesh it out making a novel out of tiny idea. So what we have here is a basic premise (a bit Dostoevskian – am I strong enough to kill and remain myself and don’t feel guilty so I can live without conscience getting in my way of living) and then the whole plot of the author going through the motions because the end result is already known from the start. It was tiresome. Even though Westlake complicated the plot with sideline difficulties (the old motives livened), and these difficulties were fun to read, still – the basic idea was too thin for a novel.

The narrator asks not for empathy but for pity. All his actions are exercies in futility. And this is his unreliability – he should have seen from the start that there wouldn’t be any rest for him because he can’t eliminate all the obstacles. I found that the narrator is smart and intelligent enough to realize that all his effors would be futile. Maybe Westlake should have tried harder to make his narrator more naive.

The small paradox of the novel is that the narrator is a SF fan, and the whole novel, a bit dated, feels like SF-ish story about time travel noose. No matter how many people you kill you will start at point zero once again. You’ll be going in a circle.

Seems to me your criticisms would apply far better to many a Parker novel you adore, Ray. So what’s really your problem here? Because I don’t think you’re being honest here about why you don’t like this book (that was pretty much universally praised by critics, and greatly outsold any Parker novel ever published, not that this proves anything, but it’s an objective fact).

Yes, it’s a novel of ideas, but not just ideas. It doesn’t get bogged down in endless minute detail, which I have to tell you, is my problem with American Pastoral, which I’m trying to read now, and it’s this magnificent ponderous white elephant of a book; Roth is maybe the most stupendously gifted American writer of the 20th Century, and boy does he ever know it, and he wants everybody else to know it too. And the points he’s trying to get across get lost in the literary pyrotechnics–he doesn’t pare it down, keep it simple, and there’s a great story in there, which just takes too long to tell. It’s more about the narrator than it is about anyone else, and of course the narrator is Roth under another name. I don’t think it’s nearly as good a book as The Ax, and yeah, I’m prejudiced, and it’s an objective fact that it won a Pulitzer, and I can’t deny Roth is a better writer than Westlake. I just don’t think he’s as good a storyteller, or as insightful a person. Too much ego there. That’s the problem with Literary Lions. After a while, they forget the audience, and write for the critics, and the prize committees, and Posterity, whatever the hell that is.

Westlake got the length of this one just right–it’s hardly a sketch, might as well say The Hunter is a sketch–enough time to make his point, and as always he just leaves us hanging, wanting to know more. If you like it in so many other books, why not here? What’s really your problem with it? What nerves did it hit? Visceral dislike for what a story tells you can often color one’s reaction to it. (Hmm, this ties in rather neatly to our email discussion of Pauline Kael and critics in general).

The narrator is not asking for pity. He’s asking for nothing except to be understood, and by the end, he doesn’t even care about that. That’s the tragedy. That he really has become the job–he’s just a machine who makes paper and kills people. We’re supposed to grieve for that loss, for the spiritual death of Burke Devore, and for that to happen, we need to understand there was a real person there, and he hated what he was doing, but he was pulled by conflicting forces–by society telling him one thing, and showing him another. He’s become the living embodiment of his time. And mine. And yours. Like it or not.

The basic idea was too thin? C’mon. I think your problem is that it’s not thin enough. And that it intrudes on the turf of Dostoevsky, but you know what? I think Dostoevsky would have loved it. Not the reality it represented, which he would have abhorred, but what it was saying about that reality. And you know, Dostoevsky wasn’t a perfect writer either (there ain’t no such animal)–I could pick anything he wrote to pieces, without half-trying. Or anything else anybody ever wrote. That’s not what real criticism is.

Now I think you’re right that there’s something of SF in this, of Curt Clark, of Anarchaos, but you like Anarchaos, which is a much shorter book, much more of a sketch, and its premise is that one man can defeat an entire planet, an entire way of life, all by himself. Yes, it’s science fiction, and this really is not, but Burke Devore isn’t defeating the way of life he sees around him, the ‘code of ethics’ he perceives that society to be operating under–not so very different, under its pleasant surface, from that of Anarchaos. He realizes he can’t do that, so he decides to consciously operate under the rules of that society, to fully and literally adopt its code of ethics. And the reason he wins in the end, is because his assessment was correct. The End Justifies the Means. And don’t even try to tell me you don’t see that in your daily life. This isn’t just about America.

You like the Parker novels, you like mainly Westlake’s short punchy crime novels. So my hunch is that you feel like the humble crime writer intruded into a domain you felt he didn’t belong in, that he had no business writing A Serious Novel About Real Problems, and you’re probably not alone in that. People wanted this writer to entertain them, to offer them a temporary escape from those problems–and yet the book sold like crazy. Why? Because people saw the truth in it. Because things that are deeply wrong in this world were expressed in cold flat simple terms that didn’t require a degree in English lit to comprehend. A perfect metaphor, brilliantly expressed, but not concerned with how brilliant people think it is–only with conveying a point. Telling a hard truth.

And I’d say I’m sorry you missed it, but somehow I don’t think you did. And that’s why you didn’t like it.

If I were a Westlake virgin, then maybe I’d say that this is a good novel by any standards. But I’m not, and I know that Westlake could do better. Why I so like his earlier stuff is that it seems like words came first, and ideas last. First he wrote, and then what was written had ideas, ideas born unselfconsciencesly. Later – like here – ideas came first, and then he tried to put some fiction meat on this idea. The whole book screams not of anger, like it should have, but of tiredness. The prose is so uninspired, it felt labored. It perfectly matched ordinaress of the narrator. But is it good for fiction? If one picks a half-literate person to narrate, should one write half-literate sentences? It’s damaging to the style.

I wasn’t bothered, against what you said about Big Literature field intrusion, by Westlake trying to write “mainsteam” novel but still being labeled as crime writer. It never bothered me. Some say that Dostoevsky wrote crime fiction. They’re free to say so. For me it wasn’t a problem. Westlake intruding on Roth’s territory? There is never such a charge as trespassing in this matter. (I read very few Roth, but what I’ve read I liked very much.)

I felt like there was not enough substence here to require a full length work. The Ax is like a short story with some padding. And it was predictable short story. Yes, Parker books are also predictable but they are series. This is a stand alone, you expect more out of it.

A masterpiece? It got just a shrug out of me. It’s not what masterpieces usually do.

I beg to differ–I’ve shrugged at many a masterpiece, that will go on being a masterpiece, long after I’m dust. Like or dislike is a separate thing from good or bad (or great). Many a book I love I would still say was pleasant trash. There has to be that something extra–and I see it here.

You say you’d consider this a much better book if you hadn’t read Westlake before–if you’d come to it fresh–and that’s an argument for your side? I don’t think so.

Again, many a Parker novel could have been a short story–much easier than this ever could be. This requires time to establish the character, and his motives, and his journey, and to run us through his list of competitors/victims. And it is not a very long book at all. Very economical. Like its narrator.

The Hunter isn’t a series novel–it’s a novel that served as the basis for a series, but it was not originally intended to do that, and in any event, I don’t accept your contention that you expect less from series books. You expect more, because you come to each new one with strong preconceptions of what the story will be like, what the protagonists will do. This being a standalone, Westlake is much more free to experiment.

I never said Westlake was intruding on Roth’s territory (I don’t even know if you like Roth–I don’t know if I like him either, though I get the distinct feeling I would not like him personally, if we ever met, and much he cares). But I was saying that you seem to be judging this by the standards one would judge ‘a serious novel’ by. Which is fine, I think it merits that standard. All the same, it’s a crime novel. It’s a mystery (Burke proves to be a rather good detective, as well as a killer, making many a sound deduction while observing his prey). It was published by The Mysterious Press, and I’ve no doubt it was in the mystery section of the bookstores. It’s not putting on airs. It’s not pretending to be anything more than it is. Social issues in crime fiction goes way way back, you know this.

Explain to me why this should be judged any differently than Red Harvest. Which obviously NO ONE took seriously when it came out. It was just glorified pulp fiction, and it took time for Hammett to be acclaimed as a great American writer, and he’s still much less highly regarded than Hemingway (his near-contemporary), and I’m still not sure I agree with that. What Hammett and Hemingway had in common, of course, was that they both ran out of things to write about, and Hammett then drank himself to death, and Hemingway decided he didn’t want to wait that long.

Nothing is more subjective than individual assessments of prose. I mean, at least with poetry you can talk about the meter and the rhyme scheme (if any). I found the prose in this book to be incredibly powerful. And you know who writes very flat prose? Charles Willeford. Because it’s the ideas and characters being expressed that matter to him. Westlake writes the kind of prose that fits the story, the protagonist–Burke isn’t a poet. He’s a mechanic in the way he kills. A middle management type in his aspirations. And to some extent, a philosopher in his intellectual bent. None of these professions is known for producing beautiful prose. It’s a first-person narrative, and it would not work for him to be doing a lot of glorious word-painting.

Your statement about how he had the idea first, and then wrote the story–you just described most books ever written. I think he wrote this the way he wrote most of his books–he had a basic idea, drawn from personal experience and observations, and certain pre-existing fictional models. He fleshed out the characters, and he used the ‘push’ method, let the characters talk to him, tell him what they’d do next. Mainly Burke, of course. But the other characters, if less vivid, are no less believable. I totally believe versions of all of these people are out there, right now.

It’s not a 1960’s paperback crime novel, no. How the hell could it be? He wrote it in the Mid-90’s, and it was always going to be a hardcover, and the era when he did (in fact) produce most of his best work is long gone. He was supposed to keep writing the same thing forever? How can you produce anything distinctive enough to be called a masterpiece, if every book looks like the one before it?

This is closer to his 60’s hardboiled stuff in spirit than most of what he wrote afterwards. It draws on that same ethos, and hearking back to Kerr’s definition, it really sums up what he’d done across his career (except for the light farce, but there is good satire in this one). Refers to it in a variety of ways. Like when Burke talks about how thought to himself he could just rob convenience stores now and again, to support his family–then laughs to himself–the idea, him an armed robber. That works for somebody who never read Westlake before–and even better for someone who has. Well, it did for me and a lot of other Westlake readers, as you can see.

It’s more self-conscious, you say–and that’s bad? A writer can’t be conscious of what is being written about, conscious of larger issues, of what’s happening in the world, of overriding themes in history, if he or she is to produce a masterpiece? Then no Russian ever produced one. Get out of that, why don’t you. 😉

Your problem is, you’re starting with, “I don’t enjoy this” and then you try to find reasons for that, but when you look closely at your reasons, you’ll see that the same thing could be said of many things you do enjoy. I enjoyed Castle in the Air, quite a lot. I enjoyed Comfort Station as much as I’ve enjoyed any book in my life (I trust my review gave that impression). I wouldn’t call either of them a masterpiece, for any amount of money. I’ve never enjoyed anything written by Kafka (he’s depressed, therefore depressing). I’d fight anybody who said The Trial wasn’t a masterpiece.

We can agree Westlake was at his best, overall, in the 60’s and 70’s. That’s when he was at his most productive, and there was an energy to that period that could not be replicated later on–by anyone. Nobody is writing books like that now (not good ones, anyway). But that’s a separate issue. His best books come farther and fewer between in his later years, but they still happen, and this is one of them. You don’t have to agree, but you do have to accept this is the consensus opinion, and that no book ever written has ever impressed everybody.

It’s a matter of opinion, and evidence that supports the opinion. And no matter how hard your evidence is, sometimes it can’t convince (you served on a jury, you know it, I didn’t and hopefully never would). Sometimes you start a book with hope that it’s as good as they say, and in the end you’re disappointed. Somtimes it’s the other way around. I started reading it with hope that I’d like it, but it fell flat. Well, I said, no harm done. Westlake wrote better books.

He wrote a lot of really good books, and this is one of them. The jury is still out as to whether it’s one for the ages, but that’s true of all his other books as well, and most if not all of what got written in the latter half of the 20th century. We think we know what’s going to last, but future generations can overrule present-day opinions, and frequently do.

Of course it’s a matter of opinion–without subjectivity, there is no art. It’s not a mathematical equation (and qualified people argue about those as well). The evidence, such as it is, pretty overwhelmngly supports a positive opinion of the book. What can’t be gainsaid is that the book struck a responsive chord in many many people, and continues to do so. Not just in America, not just in the English-speaking world.

But in summation, no book has ever been so good as to appeal to every possible reader. For whatever reason, you aren’t receiving on the wavelength this book is broadcasting on. I’ve also had that experience–of not getting something many other people love. And like you, I assume that’s their problem, not mine. Let posterity worry about it. If there is one. 😉

Based on last week’s review, The Ax is now in my Kindle. Thanks for the introduction!

An Ax is always useful when you need kindling. 😉

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That three decades of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Manhattan to be born?

I already (mis)used that poem. At the end of my Drowned Hopes review. I said Monequois, since Manhattan is where he goes to kill. Or occasionally shop.