Wayne said, “Let me tell you the world we live in now. It’s the world of the computer.”

“Well, that’s true.”

“People don’t make decisions any more, the computer makes the decisions.” Wayne leaned closer. “Let me tell you what’s happening to writers.”

“Wayne,” Bryce said gently, “I am a writer.”

“You’ve made it,” Wayne told him. “You’re above the tide, this shit doesn’t affect you. It affects the mid-list guys, like me. The big chain bookstores, they’ve each got the computer, and the computer says, we took five thousand of his last book, but we only sold thirty-one hundred, so don’t order more than thirty-five hundred. So there’s thinner distribution, and you sell twenty-seven hundred, so the next time they order three thousand.”

Bryce said, “There’s only one way for that to go.”

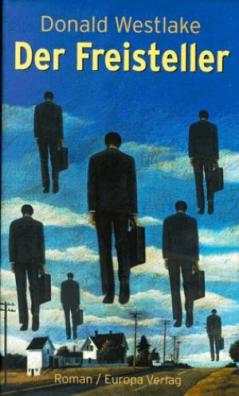

As has been made evident many times in the past here, I enjoy trying to guess which past works of fiction might have helped inspire whatever Westlake opus I am reviewing at a given moment. You may not necessarily agree with my guesses, but we certainly agree that’s what they are, and no doubt I’ve been wrong sometimes. The exercise is, nonetheless, highly pleasurable to me. Sometimes Mr. Westlake deprives me of that speculative pleasure by making his debt to another writer so blatant and unequivocal that it scarcely seems worth the mentioning.

As is the case with this book, but since Valerie Sayers (at that time the author of five novels and a professor of English, at Notre Dame no less) completely failed to mention that debt in her well-written and somewhat condescending review for the New York Times, I might as well get it out there, just to make sure we’re all on the same page.

Not a Hitchcock buff, Prof. Sayers? I won’t even inquire about Highsmith. Why does the Times so frequently choose non-mystery authors to review mystery books? A mystery in itself. Perhaps they confused her with Dorothy? An idle whimsy, never mind.

Now in all fairness, maybe Sayers (a South Carolinian of Irish Catholic descent, out of the Flannery O’Connor school, and that’s all fine by me) thought the similarity was too obvious to mention as well, or she figured all genre lit is derivative. (Southern Gothic isn’t a genre, you see–it’s a subgenre. Entirely different.) Or maybe she didn’t want to sound like she was crying plagiarism when all she really wanted was to deride Westlake’s shallow characterization and over-conceptualized plotting. But I strongly suspect she never made the Highsmith connection at all. Maybe if there’d been a tennis match or a carousel in Westlake’s book? Oh, that was mean.

It is not plagiarism, in and of itself, for one writer to react to another. There is no writer worth talking about who does not do this habitually. With her own book, Highsmith was clearly reacting to Dreiser, not to mention Dostoevsky (and they were all reacting to Poe). Westlake might have been a bit less careful here than he would have been had Highsmith been alive, and had he not been under the gun a bit (we’ll talk about that), but it’s really no different than his various creative reworkings of Red Harvest. Less enthusiastic, perhaps–more self-conscious–an older man’s book.

A summary online search reveals that pretty much everybody other than Sayers made mention that Mr. Westlake was fishing with a borrowed hook here. He wasn’t trying to hide it, and it wasn’t something you really could hide, from anyone who knew the genre at all. You’re supposed to see the influence, think about it, what it means, compare and contrast.

Strange that Sayers would say in her review that the story Westlake tells here isn’t about character, when it’s riffing on the work of a writer who virtually drowns you in character, after first hitting you with an oar, and throwing you over the side. Highsmith’s morbid missives take place more or less entirely in the heads of one or several people, expressing to us what seems to be their every waking thought (without going full stream of consciousness, like Mr. Joyce and his many imitators), which makes her work, in equal measure, fascinating and frustrating. She writes good stories, but she’s primarily interested in aberrant dysfunctional personalities, and she was to all accounts a ranking authority on the subject.

(I’m being territorial here, I’m quite aware, about the Times review, another weakness of mine. Valerie Sayers is a very fine writer, and has a sharp eye for detail–many trustworthy people have said so, and looking at a sampling of her work, I saw no reason to doubt them. She got another novel out in 2013. A university press this time; her relationship with Doubleday must have ended by the time she wrote her review of The Hook, for reasons that The Hook might indeed help illumine–she grudgingly concedes Westlake knows his onions when it comes to the world of publishing.

Let me say in passing that a quick glance at her resumé and a general working knowledge of human nature gives me the distinct impression that she would have needed to be a living saint to not have had a hostile reaction to this book, hardly Westlake’s best work, but there’s no indication in her review that she’s ever read anything of his before, even The Ax. She almost certainly hadn’t read Highsmith, and makes a passel of assumptions no dedicated mystery reader ever would. If her review is a touch on the jaundiced side, I blame the Times for assigning it to her in the first place.

Westlake was known to write critically of other people’s books as well, often for the Times. I think he was a more perceptive critic than Sayers, but I would, wouldn’t I? Scratch a writer, find a backbiter, one of his themes here. Maybe that entire practice of the literary circular firing squad should be reconsidered.

He could well have gotten a crack at one of hers at some point, except she didn’t publish any books at all between 1996 and 2013–you see my point about how this one might have rubbed her the wrong way. Her 1996 book doesn’t seem to have gotten a Times review. Publisher’s Weekly sort of gently panned it. Her very well-reviewed 2013 offering seems to be a metatextual ode to baseball, certainly an under-covered subject in highbrow lit, and maybe I better get back to Westlake before I drown us all in sarcasm.)

Westlake, to be sure, liked to get at character both more obliquely and concisely than Highsmith did in her novels–he was the master of the thumbnail portrait, particularly when writing as Richard Stark (the part of himself that most resembled Highsmith), and he liked to let the actions of the characters tell us who they were as much as possible, while still reserving the omniscient narrator’s right to sum them up.

But he, like Highsmith, was all about identity, how it changes in response to external stimuli, exigencies beyond the individual’s control, and most of all our relationships with others. His protagonists usually coped better with the dire situations he put them in than hers did. Not always, though.

So yes, he took a stripped down plot device from a famous mystery novel (less famous for the book than the movie, the latter of which I’d summarize as a more efficiently told story about far less interesting people, probably true of most Hitchcock adaptations), and I’ll just say it now–he did not improve on the original, any more than The Master of Suspense did. Did he expect to? I don’t know. But he clearly thought there were things he could do with the basic premise that Highsmith did not, otherwise he wouldn’t have tried.

Really, the author he was most obviously copying from here was himself. In my review of The Ax, I referred to an essay Westlake wrote but never published, now featured in The Getaway Car, in which he expressed his frustration that he was having ‘second novel problems’ after publishing scores of novels. His editors, publishers, agents, spouse, etc, all told him that whatever book came out after The Ax under his own name had to be special, couldn’t be humorous, couldn’t be Dortmunder, couldn’t be some sexy tropical romp. It had to be bloody, hard-edged, suspenseful, and thought-provoking. In other words, they wanted him to prove The Ax wasn’t a fluke. (I might personally observe that masterpieces are all flukes, by definition, but I wasn’t involved in that conversation.)

The general sentiment was something along the lines of “This was your greatest commercial and critical success ever; now go do it again.” Easy for them to say. So anyway, he had a bunch of ideas, many from past books of his (Cops and Robbers, A Likely Story, others), but he clearly did read (probably reread) Highsmith’s book around this time, and saw so much more clearly than most ever would, what Highsmith was getting at with it–and where she’d gone wrong, because as powerfully unsettling a first novel as it is, it’s also crammed with journeyman blunders that would have made his typing fingers itch, and of course he and Highsmith would not be of a like mind about everything (a serious understatement). And anyway, a good story is always worth revisiting, updating.

She might have been in his mind then because of her recent death, in 1995. Since she and Westlake shared a publisher at one point–reportedly not a happy time for Otto Penzler–there’s no way she wasn’t aware of Westlake as a writer, but I don’t know which of her contemporaries she read, or whether she liked any writers other than her patron Graham Greene (I think they mainly just corresponded, probably an aid to friendly relations). Liking people was never really her thing. But this novel we’re looking at strongly suggests that writers having issues with other writers is not just a Highsmith thing. Cats on a hot tin printing press.

I’m not clear on when he was first approached to write a screenplay adaptation of Ripley Under Ground–the film was produced in 2003, but as was frequently the case, they didn’t use much if any of Westlake’s treatment, and went to another writer after him, which would have drawn things out. So a very good chance this book bears some connection to that project, and the reading he’d have done for it, to get her voice right.

I understand the finished film was terrible, not that I’d know, since it’s damned difficult to find. I’ve read the novel, which I’m inclined to call the best thing of Highsmith’s I’ve read thus far–not quite as good as The Ax, but it’s close–her career batting average was better than his, but she showed up to play a lot less often. Anyway, a masterpiece is a masterpiece, and to rank them is a waste of time.

I’ve just finished Strangers on a Train (I do my research), and I get the feeling she spent much of her subsequent career reworking that story, trying to fix it, with varying levels of success. Like Westlake, there were other directions she might have gone in as a writer (see Carol, originally known as The Price of Salt, which got published right away, unlike Westlake’s Memory), but she found a comfortable commercial niche in crime–comfortable for her in ways beyond the commercial. As many had learned before her, and since, you can get away with things in that genre that would raise too many eyebrows in a ‘serious book.’ And make a nice living doing it–she left a substantial estate behind when she died, though no heirs to enjoy it.

I’ve still read relatively little of her, but I’m in the process of emending that deficiency now, and for all her failings as a person, as a writer I consider her one of our very best, a lone sentinel on the ramparts of social alienation, with some troubling insights to share. A true American original. Who never much liked Americans either, but it would take too long to list all the subsets of humanity Patricia Highsmith disliked–easier to just say she didn’t like humans. Least of all herself. We can all relate, sometimes.

It’ll take me a while to get through her. She isn’t someone you necessarily want to binge-read. That could be deleterious to your mental outlook. Unlike Westlake, whose range of interests and voices and moods could seem unlimited, she was very intently focused on a small handful of themes in her novels, and really just one dark prevailing tone–both a weakness and a strength. As was Westlake’s need to keep changing up. Which he was not, as mentioned, permitted to do right after The Ax. And hence The Hook. Not as startlingly original as the book that inspired it, or as searingly relevant as the book it was supposed to serve as the informal follow-up to, but a book has to be evaluated on its own merits (if any), so let’s do that now.

Bryce Proctorr, best-selling author, is doing research for a novel at the Mid-Manhattan branch of the New York Public Library (not the grand stone ediface with the lions, but the much less distinguished-looking glass & steel structure across 5th Ave. from it). It seems he’s not doing research for a book he’s working on, so much as harvesting background material on various exotic locales he might set a book in, if he ever got an idea worth pursuing.

His publishing niche seems to be mainly books about foreign intrigue and adventure, espionage, that sort of thing. Along the lines of Tom Clancy, Clive Cussler, and similarly lucrative. That most contradictory of creatures, a celebrity scribbler. One of his many readers recognizes him there, asks for his autograph, and he’s outwardly polite, inwardly bored, happens to him all the time. Then he recognizes someone.

Wayne Prentice. Also a novelist, also doing research. He and Bryce used to know each other, back when both were struggling to make it. They lost touch, haven’t seen each other in twenty years. (Valerie Sayers was struck by their last names–‘Proctor and Apprentice?’ she mused. She somehow didn’t twig to the fact that their first names combine into Bryce Wayne. Because they will become each other’s alter egos, secret identities. I mean, seriously, how hard a reference is that to spot, if you’re actually looking for hidden meanings? I’m sorry to keep bringing this up, it’s just irritating to me. It was probably more amusing for Westlake. He got used to the critics underestimating him. Beneath the radar once more.)

Bryce hesitates before approaching–the perils of wealth and fame–suppose Wayne hits him up for money?–but he’s curious, and they were friends, and he knows he’s not really getting anything professional done at the library–this will be a welcome distraction. Wayne is likewise both delighted and embarrassed to see Bryce. They decide to adjourn to a nearby bar, and catch up. (They aren’t on a train in the late 40’s, when rich people still took trains, so there’s no private drawing room they can chat in.)

As they sip a pair of Bloody Marys (okay, Sayers couldn’t have missed that, no need to belabor the obvious), Wayne opens up about his professional woes. He’s not researching a novel. He’s looking up colleges out in the boonies that might hire him to teach; writing, English, whatever. His career as a novelist has itself become an exercise in fiction. Nobody will publish him, and a writer who can’t get published isn’t a writer anymore, in his view of things–just a hobbyist.

He explains to Bryce about the bookstore chains, the computers keeping tabs on your sales, the ever-declining sales, leading to less and less assistance and promotion from the publisher, which leads in turn to still further declines in sales. He was successful enough at first, but the new publishing landscape is merciless to writers who are established enough to command a decent advance, but not famous enough to deliver the big numbers. He got around this for a while through a subterfuge that nobody understood better than Donald E. Westlake.

“I’ll tell you a secret,” Wayne said. “All over this town, people are writing their first novel again.”

It took Bryce a second to figure that one out, and then he grinned, and said “A pen name.”

“A protected pen name. It’s no good if the publisher knows. Only the agent knows it’s me.” Wayne had a little more of his Bloody Mary and shook his head. “It’s a complicated life,” he said. “Since I did spend that one year in Italy, the story is, I’m an expatriate American living in Milan, and I travel around Europe a lot, I’m an antiques appraiser, so all communication is through the agent. If I have to write to my editor, or send in changes, it’s all done by E-mail.”

“As though it’s E-mail from Milan.”

“Nothing could be easier.”

Bryce laughed. “They think they’re E-mailing you all the way to Italy and you’re…”

“Down in Greenwich Village.”

So Wayne Prentice became Tim Fleet, and for a while, Tim Fleet was a successful writer, getting bigger advances than Wayne had recently, because the computer didn’t know him. It wasn’t perfect–no way to do book tours, promotion was problematic, but they were evaluating each book in its own right, not on the basis of past track record. And eventually the computers caught up, and the same thing happened all over again. Wayne doesn’t think he can pull the same trick twice. So he’s worked up a resumé for the colleges, and he’s depressed as all hell about it.

If the goal of fiction is indeed to ‘write what you know,’ Westlake could not be on more solid footing here. Professionally, he was roughly equi-distant between Bryce and Wayne–never a best-selling author, but well-established enough under his various names that the bookstore computers could only hurt him so much. He did, in fact, think about taking a teaching job at one point, but more because revenue from script-writing had flagged. He never (that we know of) had a fully protected pseudonym that even the publisher didn’t know was him, but after the Samuel Holt fiasco, he certainly must have regretted not giving that a try.

Think for a moment, before we proceed, how incredibly difficult it is to make your living as a novelist in the modern age, not that it ever was easy. Think about how many people are lining up for their share of an ever-shrinking market–because there is still probably nothing anyone dreams of more than saying at some social gathering “My new novel is in stores now.” It’s the damn 19th century romantic movement. Used to be nobody of any substance wanted to admit to writing fiction. Or to being an actor. Those were the days.

Rich famous people like Bill O’Reilly, who have absolutely no reason to write a novel (and 99.999% of the time, no ability) do so anyway, because it’s just such a neat thing to be able to say. Admit it–you’ve fantasized about having a book in stores, standing by the book rack, holding a copy with the photograph of you on the back dust jacket exposed, waiting to be recognized. I certainly have. Everybody who has ever read a novel has thought about writing one. Thankfully, that’s all most of us ever do, but imagine what it’s like for those who choose it as their daily profession, and don’t want to do anything else for the rest of their lives.

A handful will, to be sure, gain such a reputation for this or that book that they can more or less live off of that forever (looking at you, J.D. Salinger, and maybe you too, Miss Harper Lee, which isn’t fair, since neither of you are living at all now), but what kind of life is that? If you make furniture for a living, if that’s what you love to do, would you be happy knowing that you’re so famous for this one table you produced that you don’t ever need to make another one, and if you ever did, people would just compare it unfavorably to the earlier one?

Let’s say you had this amazing sexual encounter with a stranger once, and you were on fire that night, performed beyond your wildest expectations, and when it was all over, your partner said, with hushed reverence, “Not to insult you, or demean what you and I just shared, but I feel I must leave two hundred dollars on the nightstand.” And you take the money, not feeling at all dirtied, but rather ennobled, and you treasure that achievement always, as well you should, and maybe it even happens a few times more, though the stack of bills by the bedside keeps shrinking.

Even so–would you then, when asked at a party what you do for a living, declare with pride, “I’m a hooker!”? Of course not! Because to do something once, or even several times, is not the same thing as making it your job. Your job is what you do, day in, day out, until you can’t do it anymore, at which point it is no longer your job, no longer who and what you are. You are only a novelist for as long as you keep writing novels, with at least a decent chance of getting them published, and the publisher pays you, not the other way around.(Okay, maybe self-publishing on the internet is blurring the lines of this definition a bit–but not much. Making it easier to kid yourself. Blogs can work too.)

So Westlake is telling us how he feels about writing–it’s more than just a job to him, it’s an addiction, a craving, a hunger he can only satisfy by getting another book on the shelves of increasingly mercenary booksellers and their cold-hearted computers. And the difference, as he put it once, between being in or out of print, is being alive or dead. And what wouldn’t you do to keep that? To keep your very sense of selfhood alive a while longer?

And even though Bryce Proctorr is a famous wealthy novelist, who hit it big soon enough that he never even heard about any of this computer crap until Wayne told him, he’s got his own identity crisis going on. He’s in the middle of a bitter divorce battle with his second wife, Lucie, who is quite determined to get half of everything he’s got. Including half of any books he produces between now and the official end of their marriage. And the stress of all this has made it impossible for him to produce anything, for a year and a half now. He’s well behind deadline, and his editor is making politely impatient noises, that will soon become louder and more insistent.

And honestly, for all the money he’s made–Wayne tries not to gasp when Bryce lets it slip his advance is over a million–there really isn’t that much left. One ex-wife already, three kids to put through college, and he’s gotten used to the finer things in life (the more you make, the more you spend; the more you spend, the more you need to make in order to maintain your spending; the joys of the upwardly mobile lifestyle in a nutshell).

Sure, he wouldn’t be penniless if he hung it all up, but he wouldn’t be Bryce Proctorr either. He’d be some has-been hack, with no reason to go on, washed up in his mid-40’s. Never taken seriously by the critical establishment, forgotten by everyone else. Just another name you see on some tattered mass-market paperback at a garage sale. (Whatever did happen to Mario Puzo, by the way?)

And he’s just now getting a brilliant and rather evil idea (and really, aren’t all brilliant ideas just a little bit evil?), as well as providing this book with its title. What’s great about talking to Wayne is that they’re both professional storytellers, they both think in the same basic terms, speak the same language. To them, fiction is not a metaphor for life, so much as life is a metaphor for fiction.

“Wayne, listen,” Bryce said. “You know how you–You know, you’re working along in a book, you’re trying to figure out the story, but where’s the hook, the narrative hook, what moves this story, and you can’t get it and you can’t get it and you can’t get it, and then all of a sudden there it is! You know?

“Sure,” Wayne said. “It has to come, or where are you?”

“And sometimes not at all what you expected, or thought you were looking for.”

“Those are the best,” Wayne said.

“I just found my hook,” Bryce told him.

Wayne has a book he can’t get published–written by Tim Fleet, who almost nobody knows is Wayne Prentice. Bryce says that can be his next book–he’ll just rewrite it enough so the few people who read the manuscript when it was making the rounds won’t recognize it. Proctorr-ize it. He’s read some of Wayne’s stuff under the Fleet name, liked it–he knows Wayne is good enough to impress his publisher, once he’s decked out in the Emperor’s old clothes. He’ll split his advance with Wayne, 50/50–over half a million bucks.

Wayne can’t believe Bryce is even suggesting this, though in fact it’s a very poorly kept secret that both Tom Clancy and Clive Cussler have done this multiple times (Drowned Hopes contains a reference to a writer named Justin Scott, a crafter of nautical adventures, who is also known to have produced novels of the same general type that were accredited to the Clive Cussler brandname–probably most of Cussler’s readers never noticed the difference, except maybe to say “Hey, Clive’s stepped up his game with this one!”), and they were both probably a lot less generous in terms of the split. Um–now that we’re on the subject– why so generous, Bryce?

Because there’s a catch. A hook, if you will. The book needs to be submitted soon. The divorce may drag on for years. Lucie will get half the advance if the book is completed before the divorce is final. Bryce needs his half, in order to go on living in the manner to which he has become accustomed. For Wayne to get Lucie’s half, Lucie’s gotta go. He wants Wayne to kill her. They may not be complete strangers, or on a train, but it’s close enough. In return, Bryce will sacrifice his own sense of professional pride on the bloody altar of necessity by using a ghostwriter, which for a novelist is probably the more serious crime of the two. So still trading murders.

Now. Here’s my question. Did Westlake start out writing another book along the lines of A Likely Story, that masterful and murder-free satire of the publishing biz that hardly anybody read? Only to then be informed by various persons in authority that satire is well and good, but if he wants this book to sell, he needs to recognize that people will expect some kind of criminal activity from him, such as murder, and all the more after The Ax and the return of Richard Stark (his Tim Fleet) reestablished him as something more than just that guy who writes comic capers about baffled burglars.

And at the same time, he was in the early stages of adapting a novel by the late Ms. Highsmith into a movie, and he was not just reading that specific book by her, and he saw how her narrative hook in her first and still best-known novel–and the ideas behind it, the sense of compromised identity, a dark relationship between secret sharers (forgot to mention Conrad on Highsmith’s list of influences) that corrupts and destroys both protagonists–could fit into what he was doing here. Or maybe he intended all this from the first. I’m just curious. Because in a certain weird way, this book is a collaboration between him and a writer he may never have even met.

But suffice it to say Valerie Sayers was far more correct than she knew when she said this was a sort of meta-textual commentary on the writing of genre books–it’s a meta-textual commentary on the career of its author, and many another as well (I still think Sayers felt more of a sense of self-recognition there than she was comfortable with). But she sort of sniffed a bit when she said it, dismissing the effort as somehow trivial, and was she right to do so?

Is this an unsatisfactory compromise of a book, stuck between two modes of storytelling? Pretending to be a nice diverting suspense novel about murderous writers, while really playing around with another writer’s much earlier idea, turning it into a way to comment on the relationship between fiction and life?

(Though I might mention on the side, because I apparently can’t help myself, that I noted Sayers doing something quite similar in one of her books I was leafing through last week, that was published a few years before The Hook came out. This character of hers, an aspiring writer, is right in the middle of a dramatic situation with a woman he’s involved with, and even as he deals with that sticky situation, he’s thinking to himself how he’s going to have to rewrite the book he’s composing in his head about their relationship to accommodate his altered perception of her. Writers probably can’t stop themselves from doing that, fictionalizing daily existence, while cannibalizing daily existence for the building blocks of their fiction–but honestly, can anybody stop doing that these days? David Copperfield was doing it back in 1849, and it’s only gotten worse since then.)

So I’m only a few pages into the book here, but we bloggers have our own self-imposed deadlines to deal with, internalized editors nagging us, and I’m sure I’ll have many more snarky and unfair things to say about Valerie Sayers’ review in Part 2 (why does she get paid and I do not!), but I will try to actually finish the review next time, and if I fail in that attempt, well, it wouldn’t be my first three-parter, would it now? Here’s hoping the hook is sufficiently well stuck in your mouths for you all to come back and find out. See, I really am a hooker.