This began Rabe’s first effort to develop a series character, beginning with a book called Dig My Grave Deep, which is merely a second-rate gloss of Hammett’s The Glass Key, without Hammett’s psychological accuracy and without Rabe’s own precision and clarity. The book flounders and drifts and postures. The writing is tired and portentous, the characters thinner versions of Hammett’s. The Ned Beaumont character is called Daniel Port, and at the end he leaves town in a final paragraph that demonstrates how sloppy Rabe could get when he wasn’t paying attention: “Port picked up his suitcases and went the other way. By the time it was full dawn, he had exchanged his New York ticket for one that went the other way.”

_________________________________

Why would anyone ever want to read a book called Kill the Boss Goodbye? And yet, Kill the Boss Goodbye is one of the most purely interesting crime novels ever written.

Here’s the setup: Tom Fell runs the gambling in San Pietro, a California town of three hundred thousand people. He’s been away on “vacation” for a while, and an assistant, Pander, is scheming to take over. The big bosses in Los Angeles have decided to let nature take its course; if Pander’s good enough to beat Fell, the territory is his. Only Fell’s trusted assistant, Cripp (for “cripple”), knows the truth, that Fell is in a sanitarium recovering from a nervous breakdown. Cripp warns Fell that he must come back or lose everything. The psychiatrist, Dr. Emilson, tells him he isn’t ready to return to his normal life. Fell suffers from a manic neurosis, and if he allows himself to become overly emotional, he could snap into true psychosis. But Fell has no choice; he goes back to San Pietro to fight Pander.

This is a wonderful variant on a story as old as the Bible: Fell gains the world and loses his mind.

___________________________________

And next, published in May of 1960, Rabe’s sixteenth Gold Medal novel in exactly five years, was Murder Me For Nickels, yet another change of pace, absolutely unlike anything that he had done before. Told in first person by Jack St. Louis, right-hand man of Walter Lippit, the local jukebox king, Murder Me For Nickels is as sprightly and glib as My Lovely Executioner was depressed and glum. It has a lovely opening sentence, “Walter Lippit makes music all over town,” and is chipper and funny all the way through.

All three passages clipped from the essay Peter Rabe, written by Donald E. Westlake in the late 80’s, now collected in The Getaway Car.

I’ve no idea how many mystery authors have rewritten The Glass Key over the years, but I’m pretty sure only Peter Rabe rewrote it three times. Westlake easily spotted the first duplicate key, as you can see up top, and hated it. He probably saw Rabe had returned to that well twice more, but liked those books too much to reduce them to mere ‘glosses’, and so held his critical tongue.

I’d say his critiques of Rabe’s first Daniel Port novel could be applied to the Hammett novel Rabe was copying. Hammett was the one crime writer Westlake could not critique incisively, or perhaps at all. Too close. Too personal. Like a bishop giving God a bad review.

I don’t think Rabe would have minded if Westlake had said that he’d rewritten The Glass Key three times (Westlake rewrote it once, and we’ll get to that)–he made it known that he’d appreciated Westlake’s pans as much as his plaudits, since the pans proved the plaudits were sincere. Nor was Westlake disparaging him by seeing where his influences lay. All writers begin, to some extent, by copying those they admire. But with repeated effort, copies may take on a life of their own and even surpass the original, in some respects at least.

In a December 1986 letter to Rabe, that was also published in The Getaway Car, Westlake made no bones about his debt to the older wordsmith, who he had a lot of questions for, preparatory to writing that essay. They had never met or corresponded, and not presuming Rabe would have heard of him, he explained that he’d written a number of books under the name Richard Stark, and they had been stylistically influenced by Rabe’s work in the 50’s and early 60’s. He went so far as to say he’d drained Rabe’s blood.

(Rabe’s first marriage was to a woman named Claire Frederickson, and I wish I could write Westlake now to ask him if that’s a coincidence. To which Rabe, a professor of psychology, therefore a student of Freud, would probably say there’s no such thing.)

My feeling about all the duplicate keys, good bad and indifferent, is that they are not mere copies of the original. (A gloss is, after all, a commentary on a previous text, and they have their place in literature). They are, I believe, attempts to fix the problems in Hammett’s novel–but also to use the same basic story to get some different points across.

Nothing new about that. Many ancient myths–such as that of the Pandavas in The Mahabarata–have been retold many times over the centuries, and each new telling has its own spin and sensibility. You can’t own a story, no matter what copyright law says (for which you should probably ask a copyright lawyer). You own the specific way you told that story.

The same is true, incidentally, of the gospels, which is why it’s stupid to try and meld them together into some cacophonous concordance for tawdry reasons of dogma. Mark does not agree with Matthew does not agree with Luke and nobody agrees with John. You can admire a book and still want to turn it on its head, make it tell your truth.

A look at Rabe’s overall body of work shows that he was interested in depicting ambitious men, often trying to rise to the top of some criminal empire, and ultimately falling prey to hubris, and the emotional conflicts it gives rise to. The hunger for success at war with the need for love. Identity crises that, more often than not, end tragically.

But something about The Glass Key interested him–suppose the man wasn’t that ambitious? Suppose he didn’t want power? Suppose he wanted to walk away from it all? Suppose he was undyingly loyal to the man he worked for, but had hitched his wagon to a falling star? Suppose he was just somebody who enjoyed the daily scrum of a semi-licit business, but felt like maybe it was time to go fully legit? All these things are suggested in Hammett’s book. None are fully spelled out. The Glass Key is ultimately about a friendship that founders. There are other things to say with the underlying structure of the narrative.

And maybe now I better get to laying out what they are, because reviewing three novels in one article smacks of hubris. Let’s start with the book Westlake hated, that I think he was a little unfair towards, but you’re cruising for a critical bruising when the title of said book is–

Dig My Grave Deep:

“Tell me again, Danny.”

“I want out, that’s all.” Port tried to hold his temper, but it didn’t work. “I want out because I learned all there was: there’s a deal, and a deal to match that one, and the next day the same thing and the same faces and you spit at one guy and tip your hat to another, because one belongs here and the other one over there, and, hell, don’t upset the organization whatever you do, because we all got to stick together so we don’t get the shaft from some unexpected source. Right, Max? Hang together because it’s too scary to hang alone. Well? Did I say something new? Something I didn’t tell you before?”

“Nothing new.” Stoker ran one hand over his face. “I knew this before you came along.” He looked at the window and said, “That’s why I’m here till I kick off.”

The only sound was Stoker’s careful breathing and Port’s careful shifting of his feet. Then Port said, “Not for me.”

Series characters are good business for a genre author (repeat business is always good), but it’s hard to strike a good balance with them–you can end up telling the same story over and over or you can be all over the place, seeking ever stranger variations on a theme, thus losing that sense of continuity that makes the form rewarding. And most significantly, in a genre crammed with surly sleuths, how do you stand out from the herd?

With a peripatetic former criminal forced to play roving detective, was Rabe’s idea–lifted from Hammett–continuing, in effect, the saga Hammett hinted at with Ned Beaumont leaving the town he’d helped corrupt with a girl who had despised him for it; never looking back, but presumably not settling down and becoming a solid citizen, because that isn’t his nature.

(It should be noted, Hammett only ever wrote one story about Ned Beaumont. There may have been reasons for that unconnected to his writer’s block. Some characters just don’t have a second act. Most of them, really. Imagine a series of whaling novels about Ishmael. And really, there was no need for us to ever hear from Huck Finn again.)

Rabe seemed to think it was worth trying–possible Gold Medal suggested it to him after he completed the first Daniel Port book, and he figured ‘what the hell?’ (They had the best pay rates in the business.) This would track very nicely with the origins of many other series characters, including one we’ve spent some time discussing here. But Port is no Parker–even though he may have influenced Parker, if largely in a negative sense. What not to do.

Whether he’d planned it this way or not, Rabe cranked out five increasingly aimless sequels to the first Port book, and the last is the only one Westlake liked. I haven’t reread it–I agree it’s better written than most, and the girl is really something, but I remember some serious problems with it–it’s set in Latin America, like many of Westlake’s novels (but none of his best ones).

So maybe just to be contrary (since even I don’t think Mr. Westlake is always right), I’m going to say the first novel is best. Because it’s the one story this glossed-up Ned Beaumont was designed for. In the five subsequent entries, he’s a shark out of water, flopping around on dry land, and it’s every bit as ungainly as it sounds. One character in search of a point.

Not as subversive a rewrite as Wade Miller’s, and unlike James M. Cain’s, it sticks very close to the main outline of the original, while streamlining it a lot–but I think it does fix at least some of the problems in Hammett’s narrative–and his hero. A tighter piece of work, with all the sex and violence and cutting to the chase one expects from a Gold Medal p.o.–but it does somehow lack conviction. Particularly the ending (of course I felt the same way about Hammett’s ending).

(And now I’m wondering–if Gold Medal did convince Rabe to bring Port back, did he have to rejigger the finish? His protagonists don’t generally get happy endings–happy being a very relative term in this sub-genre, but I’d almost rather be a character in a Kafka story than a Rabe novel. Just because Beaumont walks away in one piece doesn’t mean Port originally did, since this is a revisionist take on the story. Westlake knew all about that kind of thing–we owe twenty-three of the twenty-four Parker novels to an editor at Pocket Books issuing a reprieve for the heartless heister.)

Daniel Port doesn’t like his career path anymore. Maybe he never did. His job is to solve problems for his aging mentor, named Stoker, the boss of Ward 9, in an unnamed town somewhere in the midwest. It’s not really clear what this outfit does, other than fix elections–some gambling here, a little prostitution there, political graft whenever. There’s a reform party–but they’re crooks as well. Using the press to undermine Stoker and get their own guys in (again, straight from The Glass Key.)

The Stoker mob is connected to organized crime nationwide, and they’ve got a lot of well-armed tough-talking hoods–and as you’d expect in a Glass Key rewrite, they’ve got local competition looking to take over. Uneasy hangs the head and all. Stoker needs his errant knight to stay in the game, if he’s going to hang onto his throne. But Port’s had enough of being a vassal, and he doesn’t care to be king himself after Stoker dies.

They’re close–not brothers from different mothers, like Beaumont and Madvig–more like Stoker’s a surrogate dad for Port, who lost his younger brother to the organization–kid followed Port into the Stoker mob, after they did their stint, and somehow managed to catch a bullet after surviving WWII. Port doesn’t blame Stoker, of course–he blames himself. He’s one of those crooks with a conscience you meet in crime fiction (maybe not so often in reality).

And he’s got a caretaker complex. He feels responsible for people he likes, will go to extraordinary lengths to help them, a theme that resonates across the entire series. Knowing this about his protege, Stoker plays Port like a harp–if he can’t bribe or intimidate him into staying, he can guilt him into it. Port knows what Stoker is doing, but feels like he’s got to pay off a debt of honor he doesn’t really owe.

There’s a move from the city to demolish Ward 9 and replace it with new housing–this would effectively destroy Stoker’s power base, leaving him vulnerable to the opposition. Port agrees to fix that problem prior to going. While Stoker’s other main lieutenant, a mean-spirited mediocrity named Fries (don’t even say it), just keeps repeating that nobody leaves, unless it’s feet-first. His idea is that Port serves him after Stoker croaks (bad heart) and he’ll kill Port once he’s not needed anymore. Port’s not real thrilled with the company retirement package.

One thing wrong about Hammett’s version of the story is that Madvig is too much of a boy scout, trusts Beaumont 110%, even when Ned pretends for a moment to be going over to the other side. (Guys that trusting don’t survive long as crime bosses.) When Stoker finds out Port was grabbed by the other side in his town, his immediate assumption (helped along by Fries) is that Port has turned traitor. They were trying to turn him, absolutely–but Port is done with the whole dirty business. But he still nearly gets clipped, right then and there, before he talks his way out of it (shades of Devil On Two Sticks, which you can bet Rabe read avidly).

So it all plays along much like Hammett’s story, but Port isn’t much like Beaumont. He’s a lot more serious, he doesn’t gamble (except with his life), he’s not solving any murder mysteries (not a required component of the genre in a Gold Medal crime novel), and he’s got better taste in women.

He meets this girl, Shelly, the dark and lovely daughter of Mexican immigrants, whose younger brother Ramon (who she raised herself, since the parents were always working) is also tied up with the Stoker bunch–ambitious punk, probably headed for an early grave, just like Port’s brother, and of course Port’s guilty about that too, but there’s no reasoning with the guy, and Port has his own problems.

Port plants Ramon as a gardener (heh) at the home of a guy named Bellamy, leader of the corrupt Reform party, to find out what they’re planning, and she’s mad at Port about that, but then she winds up there as a maid herself, getting pawed over by the old lech, and Port’s mad about that. He grabs her, all caveman-like, throws her in his great new car Stoker gave him, in her skimpy domestic attire, and you’ve read Gold Medal novels before, right?

“Safe and prim as hell, right? What is it, Shelly, afraid I’m going to rape you?”

“You know you can’t! You know…”

“No. As long as there’s you and Nino I wouldn’t think of it. You’re not even here! And all you ever feel is sisterly love, isn’t it?”

She sat still, and Port started to think she was going to let it pass, when she suddenly swung out her arm and cracked the back of her hand into his face.

He jammed on the brake. At first he thought he was going to laugh but then felt himself getting furious.

“Stop the car,” she said. She sat crouched in the seat, and she had one of her shoes in her hand, holding it so the heel made a hammer.

Then she said again, “Stop the car and let me out!”

Port made a fast turn into a dirt lane and stopped the car. He was out before Shelly had found her balance.

The air was rainy and cool, with a strong leaf odor out of the woods next to the road, and while Port stood there, breathing it, he wondered whether she’d ever come out. Her teeth showed like an animal’s, and when she stood in the road she stopped to kick off the other shoe and then didn’t wait any longer. She didn’t wait for him to move, but came at him.

He hadn’t figured she was very strong or as determined as she turned out to be, but before he got the shoe out of her hand she had clipped him hard over the ear, had tried to knee him, and then bit his neck. He had to let go of her to get a good grip, and that’s when he stopped fighting her off. He got a hold on her that changed the whole thing, except that Shelly wouldn’t give in.

The next time she tried to knee him Port lost his temper. He picked her up, tossed her over the ditch, and was next to her when she jumped up. There was one heated look between them and then the front of her dress came apart in one loud rip. She froze, but Port wasn’t through. He reached out and tore the rest she had on, and when she tried to free her arm to claw him, he yanked it all down.

He was holding her as if she might get away long after Shelly had no such thought.

He had taken his jacket off and Shelly was wearing it, and when she had reached for the cigarette he had lit for her she left the jacket the way it had fallen because they were still far out of town. Port was surprised to see how far they had come.

She said, “Your place, or mine, Daniel?”

“Mine’s more private.”

“But mine is closer.”

“And I got better accommodations.”

“Except my clothes are at home.”

He shook his head sadly and kept on driving….

They keep on driving at Port’s apartment for several days, while Stoker frets and worries. In fact, Port has done a good job thwarting the enemy plans, has found a cunning legal loophole to keep the slum clearance from happening, which almost amounts to a good deed (it’s not designed to benefit anybody but the people planning it–it’ll just displace the bluecollars from the only homes they can afford to live in, fragment their community, destroy it. This was, you should remember, the era of Robert Moses.)

He’s found the weak spots in the opposition’s armor, their corrupt little secrets, and the only problem (as Stoker reminds him) is that only Port is smart and strong enough to pull the scheme off. Fries hasn’t got a clue.

And Port still doesn’t have a workable exit strategy, but he’s got the girl he means to exit with. He takes her shopping, then escorts her (the former domestic) to the big social event at Bellamys house. This after half-killing Bellamy earlier that day, when he and his hoodlums tried to either turn Port or kill him. (Basically non-stop violence, in this and all the other Ports, but again, you’ve read Gold Medal novels before.)

He’s there to show solidarity with Stoker, but it’s just not going to work–Stoker has a point, you’re either in or out, and Port’s trying to have it both ways. Port finally realizes it won’t work, that he’s got to cut the cord, or accept his fate. He and Stoker have their final face-off there–no matter what loyalty he may feel to his mentor, he’s got to be loyal to himself first. Even if it kills him. Even if it kills Stoker. And it does.

“Face the facts, Danny. I won’t be here much longer. Which way do you want it: With Fries under you, or you under Fries?”

Port felt the rage grow, and he couldn’t stop it this time. “To me, that’s not even a choice.”

“There’s another one. The one I told you at first.”

Stoker saw the color come into Port’s face, a thing he had never seen, and like an infection he felt his own face become glutted with blood, the heart-pound loud in his ears, and he shouted, “Take it or leave it! I’m through begging you! Take it or leave it, and I don’t give one stinking damn!”

Port’s voice came out hoarse. He controlled its strength but no longer anything else. “You go to hell!”

“Wha—”

“If I can’t get rid of you and the air you breathe, you and the Frieses and Bellamys and the big shots with small heads and the small shots with big heads, then I’d sooner crap out!”

“I’ll see you will!”

“Try it, Stoker. Try stopping me now!”

What stops, as if Port’s rage alone had done it, is Stoker’s tired old heart. Cracks his head on the stone hearth going down. Guess who the Reform mobsters try to hang a murder rap on? But Port gets out from under it with his accustomed eptitude, and informs them all–both mobs–that now he’s got the information needed to take them all down. Names, dates, places. The works. He’s leaving town, for good, and none of them better get in his way.

It’s the old fail-safe plot device (not sure how old in 1956). He’s got it set up so that if he dies–for any reason–the information goes to the press and the law. As a final parting shot, he gives the old Reform leader–the one who actually meant it, but got forced out by Bellamy–just enough intel to burn Bellamy, and regain control of the party.

This Samson’s bringing the whole temple down–but not before he leaves it. With his girl. Well, that doesn’t pan out, because the resentful Ramon (beaten to a pulp by the Reform thugs, and blaming Port for it) told Shelly Port was dead, and she left town herself, headed for the west coast. Port was going to New York (like Beaumont), but he changes his ticket and goes the other way. Doesn’t discourage easily.

And I wish Rabe had left it there, with the knight errant of noir, his liege lord no longer impeding him, riding out to find his lady love. For all the lack of conviction I lamented above, it’s still a fairly strong ending to a book that is hit or miss all the way through– though full of interesting minor characters, including a nerveless gunsel (in the sense he doesn’t process pain the way normal people do) and a hooker with a heart of brass, who may well end up with the gunsel, we never find out. I agree with Westlake that it’s not as good as Hammett’s book; except in the ways that it’s better.

Westlake, ever the word nerd, was nitpicking about the repetitive language at the end, which I’d say Rabe used on purpose–Daniel Port always goes the other way. You can say it doesn’t work, but no reason to assume he was being careless. I like it better than Hammett’s ending for Beaumont, which just sort of hangs there, like a bad joke.

We never see or hear about Shelly in the later books–Port either couldn’t find her, or she just figured she’d had enough. Different sexy broad each book–have to keep the roving hero single. He’s settled down with another luscious Latina by the end, south of the border, but he’s too far out of his element there–the book isn’t really about him, he’s just kibbitzing in someone else’s story. Rabe’s acknowledgement, perhaps, that Port wasn’t suited for a series, and then the series ended.

Rabe experimented with different styles, different types of story (as Westlake later did with Grofield, not a lot more successfully) but all Port really has, as a character, is the caretaker thing (motivation to keep sticking his neck out), the not wanting or needing a boss or steady job thing (keep him rootless, searching), the eye for the ladies thing (so horny guys will keep buying the books), and this low tuneless whistle thing he does when he’s feeling pensive (because ya gotta have a gimmick).

Once his major conflict is resolved, at the end of this book, there’s just not enough left to hang a series on. Which is why I say this book is the best of the six, since at least he does have the conflict here, even if it’s borrowed from Ned Beaumont. And I’ve got two more books to cover, so that’s more than enough about Daniel Port.

Even though in some ways I find this a more enjoyable and focused novel than the mordantly messy original that inspired it, even though I find it handles many of the story ideas more adeptly (and sure as hell has the better sex scenes), I can’t say I think it’s as good as Hammett’s book. Rabe wouldn’t have thought so either. And there were other variations he had in mind, so at around the same time as he wrote this one (before? after? simultaneously?), he came up with a nigh-Shakespearean syndicate saga, entitled–

Kill The Boss Goodbye:

“Look, Jordan,” said Dr. Emilson. “If Fell should leave now, that might be all he needed to go over the brink.”

Cripp sat up. He was finally getting straight answers.

“That’s my professional guess,” said Emilson, “and it’s enough to warn you.”

“Warn me?”

“Did you ever hear of a psychosis?”

It made Cripp think of padded cells and children’s games for grown men. It made him think of Fell, whom he had known for over ten years. Fell had picked him up in New York, where Cripp was making pocket money in a cheap sideshow at Coney Island. The Brain Boy with the Mighty Memory. Tell the kid the year and date of your birthday, mister, and he’ll give you the day of the week. And now the most astounding feat ever performed! Read any sentence from this paper, mister, this morning’s paper, and the kid will tell you what the rest of the paragraph is. This morning’s paper, mister, the kid’s read it once – and Fell had picked him up after the show, kept him with him ever since. A mighty memory was quite a boon in Fell’s racket. No bookkeeping, no double checks on collections, no time wasted on figuring odds and percentages. Cripp did it all in his head. He and Fell weren’t friends, or even buddies, but whatever they had between them was as close a thing as Cripp ever had with anyone. And Cripp made it the only attachment there was. It was easier that way.

“Did you ever hear of a psychosis?” Emilson had said, and right then all Cripp knew was that Fell was not like those men playing children’s games or like somebody in a padded cell. Fell was strong, always right, generous because he was big; and he could make things sure because he was always sure himself. Fell had two legs that gave him a straight, even walk. Fell was –

“Mr. Jordan, I asked you a question.”

Rabe’s other two duplicates were not so much revisions of Hammett’s story as fresh takes, inspired by it, but not following the template too closely, which explains Westlake’s (justly) higher regard for them.

He talks about this one as if Rabe wrote it after his other 1956 novel (the one we just covered), and I don’t know if that’s based on his correspondence with Rabe, or if he just assumed. I’ll just assume myself, because this is a better book–better than the book about Port, or the one about Beaumont. Better than 99% of 50’s crime novels.

But it’s also a book that reverses the polarity, in some intriguing ways–the Beaumont stand-in isn’t looking to leave, ever. He’s not so much loyal to the Madvig in his life as welded to him–unable to imagine life without him–content to be second banana, no agenda of his own. Not even a love interest, which I assure you is quite unique among the duplicate keys. There’s sex, because Gold Medal, but none for him.

His name is Cripp–well, that’s what they call him, because he’s got a withered leg, which he’s compensated for with a remarkable memory and an overdeveloped upper body. He’s actually the one who pulls the boss back into the game. And the boss is, to coin a vulgarism, nutty as a fruitcake, magnificently and tragically so as Lear. It’s a tragedy Robert Ryan didn’t get to play him. (maybe Kirk Douglas for Cripp, but they’d have had to beef the role up, add a love interest, because Kirk Douglas.)

The story isn’t about Cripp. He’s merely the fool to this mobbed-up Lear, head of the local gambling syndicate in some inland California town with a racetrack and a police force that looks the other way when properly greased.

The weakness Fell’s showing is mental–or really, emotional. He’s had a nervous breakdown, and he’s been recovering at a sanitarium, and you read Westlake’s synopsis. But no synopsis can ever prepare you for what follows. Because Tom Fell is nothing if not magnificent in his burgeoning madness–

Fell turned around again. He was talking to Cripp.

“Ever notice that nose on Pander? Ever notice how nice and straight that nose is?” It was another switch nobody could follow, and Fell walked to the door. He stopped there and said, “Pander used to box, some years back. Even if we hadn’t set up a fight for him now and then Pander could still have looked good. A good welter,” said Fell and started to smile. “And then he suddenly quit. Just getting good, and he quits. No heart, you can call it.”

Pander had started to hunch himself up and got ready to take his sunglasses off.

Fell continued smiling. “You see a boxer with a beautiful nose,” said Fell, “and you got a fighter without heart. Look at him.”

Millie Borden looked from one man to the other. Then she moved back. She hadn’t understood a thing that had gone on, but she understood what was shaping up. She moved because there was going to be a fight.

Pander leaned up on the balls of his feet, arms swinging free, face mean, but nothing followed. He stared at Fell and all he saw were his eyes, mild lashes and the lids without movement, and what happened to them. He suddenly saw the hardest, craziest eyes he had ever seen.

See, in some ways it’s an advantage–to not give a damn. To never count the cost. To believe you can’t be stopped. And it’s not like he doesn’t have Cripp to be his brains, or his beautiful wife to hold him together emotionally–except he’s putting unbearable stress on both relationships with his behavior. Without a superego to get in the way, rein him in, he just keeps upping the ante–he wins a lot at first. But the more he wins, the more he knows he can’t lose.

There’s some stuff about a racehorse he’s been keeping under wraps–gorgeous stuff. The writing here can make you gasp sometimes. Ned Beaumont’s card games seem very small and shabby compared to the big race, where the horse, representing nothing less than Fell’s unbridled id, delivers in a big way, beats the oddsmakers, crushes all opposition, puts Fell right back in the driver’s seat–but he can’t stop driving.

A horse knows when it’s time to stop running, cool down, eat some grass, find a mare–a madman doesn’t. He doesn’t even quite register his horse is a gelding–telling symbolism there–keeps calling him a she. “I call ’em all she,” said Fell, and then he went outside to Buttonhead. (Believe it or not, no database I’ve searched can find a thoroughbred by that name.)

Fell starts pressuring local politicians, knocking over apple carts left and right, looking to build new castles in the air–the town is all sewn-up, on the take, but the state isn’t. He’s drawing attention to himself and the organization. He’s doing things for the sake of doing them, like a shark who can’t stop swimming forward, and Cripp just watches him helplessly, knowing it’s all wrong–knowing, in fact, that Fell is sick, because the doctor told him so–but not knowing how to stop him or leave him. And he could never betray him. So he just gets dragged down under with him. Again, quite unique among the duplicates.

The bosses in L.A., who never thought much of Pander, would like to go on trusting in Fell, still can’t help noticing the lines he’s crossing, that put them in jeopardy as well–they do some research–they find out about the psychosis. The mental hospital. They dispatch a killer. Named Mound. Rabe was good with names. And killers.

The ending is abrupt, unsettling, and doesn’t tell us what happened to Cripp. What would be the point? If Mound finished him, or Pander, it would only be a mercy-killing.

The story, as I said, isn’t about Cripp, and that’s nobody’s fault but Cripp’s. He let his story be about somebody else, subsumed his identity into Fell’s. The brain boy forgot how to use his brain for himself. There’s a moral in there somewhere. About how blindly following even a magnificent madman can have fatal consequences. Imagine for a moment, how bad it would be if the madman was just a sleazy old fake, who didn’t even know his own business, his paymaster was a foreign power, and he was in charge of a whole country. Well, who’d believe that? Gotta keep these things plausible.

I’d call this the best of the duplicate keys, except it strays so far from the pattern of the master key, it almost doesn’t count. It reimagines the story to the point where it’s a different story. One reason I’m giving it less time here. (The other is I don’t want to spoil it for you.)

But Rabe had one more key in him, and this one gets my vote for the cleverest–and funniest–of all these linked stories about fixer and boss. Even though it’s not as well written as Kill The Boss Goodbye. Can’t have everything. It’s got a much better title, Rabe’s own this time, namely–

Murder Me For Nickels:

I have a rule about money, which goes: make it, spend it. It’s the nearest thing to a rule which fits the way I’ve been living through one job or another, until I put in with Lippit. After a while with Lippit, and what with the business we built, there was money left over. What I mean is, I wasn’t used to spending that much and I didn’t have the time, anyway.

That’s how I got to own Blue Beat.

This studio taped only the rare jazz for the aficionados. Naturally, the place was going broke. I had bought the place for what always comes out as a mixture of reasons: I had the dough; I saw a bargain; I like jazz; I know some of the rare musicians, whether they’re known or not. Sew it all up and call it a gamble, and maybe I got Blue Beat because of that. The Lippit operation by then was getting boring, and smooth.

Then Blue Beat made money. We only taped what we liked, but this time it paid. Next for the action, I bought up what was left of a pressing plant on the ground floor where we started pressing our own records and also did jobs for the rest of the studios in the area. Nothing big, but it didn’t lose money. The whole works was Loujack, Inc., Jack St. Louis on the top of the stock pile, but silently.

I’d rather not mix friends and business, and as for Loujack I wanted Walter Lippit to be just a friend. He knew that the outfit was there, the way you know there’s a lamp post down the street, but so what. He didn’t know — there were few who did — that Loujack was me. That would have been different. That would have been less like a lamp post down the street and more like uncle Walter Lippit observing the doings of his favorite nephew. Next, kindly interest. Next, this being all in the family, he might have dreamt dreams about mergers and empires and since Lippit was not much of a dreamer, next thing, he would grab. I’m not against Lippit — friend of mine — but I myself don’t like to be grabbed.

I love being grabbed, if it’s a book grabbing me–and tickling me to boot. Rabe, unlike Westlake, isn’t known for comedy. Nor was he half so good at it as Westlake, but in 1960, neither was Westlake.

Gold Medal published this the same year Westlake’s first novel under his own name came out from Random House (also a duplicate key), and reading Rabe’s book certainly would have given the younger wordsmith a notion that you could write a story about funny criminals and not be arch–still make it thrilling, sexy, hip (also extremely violent, because still Gold Medal).

This is all of the above. It’s also a bit clumsy and rushed at points–Rabe wasn’t used to this, he was trying something new (for one thing, it’s written in the first person, which he hardly ever used). So you have to excuse the rough spots. You’ll be well-rewarded if you do. And that Robert E. McGinnis cover alone was worth more than a measly 1960 quarter. (You can still get a decent vintage copy for twenty-five bucks or less online–go figure.)

This certainly is a ‘gloss’ on The Glass Key. (Gloss Key?) Westlake could hardly have missed that–it’s the exact same story, from the same perspective, that of the fixer, but the first person narration is new, as is the narrator. In this case one Jack St. Louis, a hard-punching fast-running girl-chasing low-flying small-time entrepreneur, right on the edge between legal and illegal, who makes Ned Beaumont look like a stick in the mud plodder. (Beaumont literally kept getting stuck in the mud, which got kind of vexing after a while.)

The gag here is that what they’re doing isn’t really criminal–they’re putting jukeboxes in bars and other establishments. That’s a crime? It is, maybe, if you kind of give proprietors the impression they don’t have any choice in the matter–but they never have to break any windows, or fingers. They’re providing a service, and making a good living by it. Jack’s doing so well, he’s started his own record label on the side (that he doesn’t want Walter to know about, see above).

Since people want to hear music when they drink, something they can relax to, tap a toe to, maybe even dance to, it’s fairly victimless. Except the people providing this service may fall victim themselves–to rival mobs muscling in. In this case, not just any mob, but The Mob, or people affiliated with it. People with names like Benotti, who Jack goes looking for in a tux, no less. He wins the fight, but these guys don’t intimidate. If Jack and his boss/buddy Walter don’t watch out, their thing will become somebody else’s thing, and they might just get murdered for nickels.

And if Walter doesn’t watch out, his current girlfriend will become Jack’s thing–Jack, whose loyalty doesn’t extend to matters of sex (very Grofield), goes to the Lippit home and finds Patty, an aspiring chanteuse hoping Walter can get her into the bigtime, all by her delectable self. They’ve been eyeing each other a while now. The moves are applied. Resistance is feigned. A zipper unzips. The deal is sealed. But neither means anything serious by it. It’s not a serious book. Though it might become one, if Walter finds out. About any of Jack’s little side-deals; the one with Patty perhaps mattering least of all (but only cows look good with horns).

Jack doesn’t solve any murder mysteries (because nobody gets murdered–even Gold Medal had to lighten up sometimes). But he does have to figure out where this new outfit muscling in on their turf came from, how to stop them, and sometimes to get into some pretty serious scuffles with them. Jack doesn’t think of himself as a tough guy (what real tough guy ever does?) but he’s learned to hit first and ask questions later, and he does pretty well in the fisticuffs department, just by moving fast and doing the unexpected, dressed to the nines while he does it, dropping hoods–and ladies underdrawers–all over town. (Jon Hamm? Oh never mind, nobody’s going to adapt it now.)

So it’s a detective novel after its own idiosyncratic fashion, but it’s much more about describing the jukebox business to us, and all the related businesses, like jobbers, record companies, etc. A lot of organized crime actually involves legit enterprises used in illegit ways, and it’s refreshing to see that done so well here. There’s no political angle, because they don’t need to corrupt any public officials to do what they do, as long as they don’t do it too loudly. There’s a wee bit of union fixing, but it’s not the Teamsters. Nobody gets buried under the 50 yard line for nickels.

So Jack goes on dancing, juggling women (Patty, but also a short stacked little brunette who also wants to be a singer, but can actually carry a tune). Juggling his job defending Lippit’s interests while trying to defend his own private business concerns at the same time.

Benotti’s bunch buy out their jobber, and now they can’t get new records for the jukeboxes. Jack’s own record business, complete with pressing plant, could address that short-term. But Lippit would want to own it himself. And Patty has found out about it. And she wants a recording contract. And Benotti, like every rival gangster in every duplicate key, wants Jack to come over to his side, or else get murdered for nickels, or at least very badly beaten up. And there are guys on their team who aren’t to be trusted. Vaudeville never saw such a juggler as Jack St. Louis

So when he finally drops a ball (or Patty drops it for him), Lippit believes he’s a traitor (which, you know….), and let’s just say none of the duplicate key bosses are as trusting as Paul Madvig.

“So what was your plan, right-hand man?” said Lippit.

“The plan was,” I said, “to help you keep playing your jukeboxes.”

“Was that the reason you snuck around behind my back and set yourself up in a legitimate business?”

He used the expression like a dirty word and I felt I should make one thing clear right away.

“Just remember it’s mine, Lippit. Not yours.”

“Sure. And you just remember that I got the union that can rock your boat.”

“How’s that going to help you?”

“It would make me feel just fine. The way I feel, it would make me feel just fine.”

Lippit doesn’t even know about Patty, and he’s almost ready to murder Jack for nickels. The friendship, that Jack valued (in spite of the bird-dogging behind Walter’s back), turns out to be built on a flimsy foundation–they never understood one another. But Walter’s not the problem so much as the guys looking to take over from him, who will murder Jack for nothing. (I can’t possibly recap all this, there’s too much, and I’m over 7,000 words)

Patty, a nice girl down deep, knows it was her blabbing on Jack that got him into this mess–she’s mad at him, for seducing and abandoning her, (and even more because his other girl can sing better than her), but she does not want him dead.

So she does the old femme fatale routine with one of his captors, distracts him, and another thrilling fight scene and a few smooth moves later, Jack’s on top again. He and Walter call it quits, more or less amicably. He and Patty go legit with the record label (and his other girl, now superfluous, is more than content with her new recording contract). Maybe the girl he ended up with can’t sing, and isn’t quite so curvy, but a gal who’ll vamp a hulking hood for you (even if she’s the reason he’s got you tied to a chair, half-conscious) is a keeper, any way you look at it.

Jack steals his best friend’s girl, just like Ned Beaumont–but it’s the right thing to do, they really do care about each other, and Walter doesn’t give a shit about either of them now (he was never that stuck on Patty to start with).

Jack leaves the organization, just like Ned Beaumont–but he stays in town, and becomes an honest businessman–well–as honest as anybody ever gets in that biz. (When did the payola scandal break wide open?–oh right, year before this book came out. Would have made for an interesting sequel.) He was headed that way already, but delaying it–putting off full adulthood–because he liked the romance of being a kindasorta crimelord’s right-hand man. This crisis forced him to stop with the fence-sitting, and he chose the other side of the fence.

Jack stops the rival mob from taking over, but he doesn’t cause any deaths in the process, and the cops never even seem to notice what’s happening. He seems happy and hopeful, when last we see him, Patty leaning on his shoulder–not a fatalist existential bone in his body. Hardly reformed. Jack St. Louis will always be a rogue, but he’s not a killer–or a hireling. He’s his own man now, with his own woman, a team–and he likes it that way. Rogues can be adults too.

It’s damned upbeat and optimistic for a duplicate key–or a Gold Medal paperback–and most of all for a Peter Rabe novel. Although after all the beatings that went around, these people should be getting dental work and maybe dialysis. Gold Medal must have had the best health plan going.

And that gets us through all the duplicate keys save one–that as I’ve already mentioned, came out the same year as Rabe’s last duplicate. It’s the other duplicate written in the first person, and the only one set in a major city (The Major City, not that I’m biased). The only one that’s really about The Mafia, and drug-smuggling, and all the things the others kind of danced around.

And it’s not upbeat or optimistic at all. Not sure what kind of health plan Random House had, but more interested in what kind of funeral benefits they offered. And yeah, I already reviewed this one. First book I ever reviewed here. Let’s see what I missed. Next time.

(Part of Friday’s Forgotten Books)

So while I wait for somebody to notice I’ve finally posted a new article (it would require another one to explain all the reasons, so let’s just say ‘Life’), something I didn’t get around to mentioning. Only just noticed it myself.

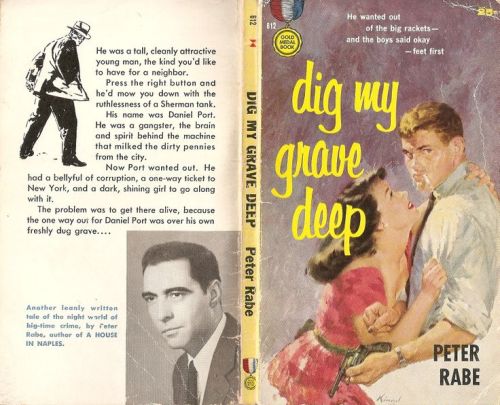

You see the photo of Peter Rabe on the back cover of Dig My Grave Deep?

You see the piano player (presumably Jack, although he does’t play piano anywhere in the book) on the front cover of Murder Me For Nickels?

That’s a Robert E. McGinnis cover, as I’ve already mentioned. (Really, the style speaks for itself.)

Compare the two images.

McGinnis really did pay attention when the books were good.

And since I pay attention to McGinnis–and am still slightly miffed I got zero comments for what I vainly consider to be semi-readable prose–I’ll post this link here.

https://dmrbooks.com/test-blog/2021/2/3/robert-mcginnis-still-kickin-ass-at-95?fbclid=IwAR3OxyfhJN0q9e-uL-5v2FJZs8YiNbXSG3HHJh8L79gIGuvS9wwqdr0TXwg

He even outlived the Trump Presidency–he’ll outlast the pandemic, bet on it.