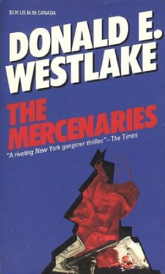

Another interesting new and young writer is Donald E. Westlake whose THE MERCENARIES (Random, $2.95) is substantial and effective–if the publisher’s “the first new direction in the tough mystery since Hammett” remains mysterious. Clay is a troubleshooter for what he does not like to call The Syndicate–an efficient, likable, understandable young man who arranges everything including, when need be, murders. When a syndicate newcomer is framed for killing a blonde, it’s Clay’s job to turn detective, to find and eventually to execute the real killer. Despite a few (probably necessary but regrettable) concessions to conventional morality, this is a largely excellent job of sustained narrative and observation within the framework of a self-consistent world, alien to law and convention. (And don’t tell me Hammett didn’t do just that in “The Glass Key.”)

Anthony Boucher, from the Criminals at Large column, New York Times, August 7th, 1960.

“Clay. Don’t tell me to don’t be silly. I know, I know, you’re fine with me, you’re a nice guy and we have a good time together, but—then you can turn around and be so cold-blooded, talk about giving somebody an accident when what you really mean is you’re going to go out and commit cold-blooded murder, and it’s just as though it doesn’t really mean a thing to you at all. There just isn’t any feeling there, any emotion. And that scares me, Clay. With me, you show feeling. One of those two faces has to be false. I’m just scared it’s the face you show me.”

“You can’t feel pity for a guy you’re supposed to kill, Ella,” I said. “Or you couldn’t do it.”

“Do you want to feel pity?”

“I can’t. That’s all there is to it, I can’t. I don’t dare to.”

“You don’t have to kill, Clay.”

“I do what I’m told,” I said. “I’m Ed’s boy, he’s my boss, he says do, I do.”

“Why? Clay, you’re smart, you don’t have to be Ed’s boy. You could be anybody’s boy. You could even be your own boy, if you worked at it.”

“I don’t want to be my own boy.”

“What’s Ed to you, Clay?” she asked me.

I lay there through a long silence, my head in her lap, her fingers soothing on my temples. What was Ed to me? “All right,” I said. “I’ll tell you a story.”

The question that nags at me is why.

Of course Westlake would start by imitating Hammett. Hammett meant more to him than maybe any other writer, certainly any other mystery writer. His second crime novel was a revisionist take on Red Harvest, a book he revisited over and over again across his career. His first major series protagonist bears more than a passing resemblance to Sam Spade, huge hands, animal magnetism, and all (though Parker has many literary forebears, as I’ve noted elsewhere). His second major series protagonist, Mitch Tobin, was a re-imagined Nick Charles, with the emotional problems only implied in The Thin Man made much more explicit, worked out in greater detail across five novels.

The Op stories, The Maltese Falcon, The Thin Man–those all resonate across many Westlake books (maybe all of them). He returned to that well over and over. I’m not sure I see any strong influence from The Glass Key, in any book other than this, the first he wrote under his own name. The Fugitive Pigeon? The Busy Body? Maybe a touch, but neither of those guys qualifies as a fixer. Butcher’s Moon has a mobbed up cop who might qualify, but there’s no close relationship between him and the crime boss, for obvious reasons. There’s a mob fixer in Kinds of Love, Kinds of Death, and that book is clearly a variation on this one, but it’s not about the fixer, or his relationship with his boss–it’s about a disgraced police detective solving a mystery for them.

The final duplicate key–the last I know of. Recognized as such at the time among cognoscenti–it wasn’t meant to be a secret, what he was doing here (both books begin with the protagonist having a confused conversation with a stutterer who is begging a favor from their mutual boss).

That capsule Boucher review up top is prima facie evidence of this recognition. Though I wonder if even Boucher recognized that The Mercenaries, as it was then called, was not homage so much as revolt. More than in any other story of his that derived from Hammett, Westlake was saying here that Hammett got it wrong. And he was drawing obliquely upon his own past experiences (that no critic knew anything about then) to say this. And I would say that all the other duplicate keys are evidence that he was not the only one who thought Hammett got it wrong. Or at least that there was room for improvement there.

But why? The very first novel bearing his name. For Random House. In hardcover. Maybe the most significant career choice he ever made. What would that book be about? He chose to make it a rewrite of The Glass Key. Which he knew had been rewritten multiple times in the past few decades. And none of those rewrites were bestsellers (as the original had been). Most had vanished without a ripple. And the writers who produced them were all damn good. What made him think he could do better? Better, perhaps, than Hammett himself? On his first try?

Before we proceed, let’s recap:

The Glass Key: A beautifully written book with a murky repetitive plot and sketchy motivations. Ned Beaumont loves Paul Madvig like a brother, is loved in return, his loyalty seemingly unbreakable. He executes his job as fixer with polished efficiency, even though he’s only been in this town about a year. And just as mysteriously as it manifested itself, his loyalty to Madvig disappears, replaced by a very unconvincing romance with the society gal Madvig has been so unwise as to fall for. He leaves town with her, no better or worse off than he was before, having cleared Madvig of murder by solving a mystery–shoring up Madvig’s power base before leaving, but leaving his friend a broken man, desolate and alone. Ned never kills anybody, though he indirectly causes a few deaths.

Love’s Lovely Counterfeit: A marginal duplicate. Cain tries not to get too close to the original, but his influence is clear. Ben Grace double crosses his boss (no love lost on either side) first chance he gets, takes charge of the organization, makes mistakes, pays the price, but he’s not bitching about it, goes out on his own terms. With Ben, it’s all about the girls–who happen to be sisters, which is where he really goes wrong, because that’s how James M. Cain rolls. Not a terrible book, but not what Cain did best, though he does add some interesting details about the way organized crime ties into politics (and the police force), and makes money primarily by entertaining the masses with illicit (or semi-licit) pleasures, such as pinball machines. Ben kills once, in self-defense.

Devil On Two Sticks: Wade Miller went back to the original idea of a mobster’s consigliere assigned to solve a mystery–in this case plug a leak. Find a mole, then whack said mole. Steven Beck feels no loyalty to his boss, nor the boss to him, but Beck is all about the job, doing it better than anyone else–he’s described as more machine than man by a lawyer working for the outfit, gifted with an ability to switch off his emotions, that fails him in the end. He’s likewise been doing this job for a suspiciously short time–just came up out of nowhere, no backstory, no explanation of how he got into this line of work. Again, a woman (the lawyer’s daughter) is the reason his Machiavellian machinations don’t work out as planned, but he leaves under his own steam, alone, having made a moral choice–that means violating his professional ethics. (Note: In the fifth Max Thursday novel published the year after this, it’s revealed that Beck’s boss and his entire organization got taken down by the law not long after Beck split for parts unknown, though Beck isn’t referenced in that book.) Beck takes out a few rival hoods who plan to kill him, and accepts the job of killing the mole once he finds him without complaint. It just doesn’t go that way in the end.

Dig My Grave Deep: Daniel Port feels a deep (if irritable) loyalty to his mentor and boss Stoker, who wants him to stay and take over once he dies, but is willing to kill Port if he tries to leave, which he’s trying to do for the entire book. Port feels a deeper loyalty to himself–he’s supremely good at his job, doesn’t really know how to do anything else, but he doesn’t think the job is worth doing, or worth the price you pay for doing it. He meets a girl (predictable, ain’t it?), who he’d like to leave town with, and she’s good with that, but he gets cheated of his happy ending, perhaps because Rabe (or the publisher) wanted more books about Port, which wasn’t necessarily a good idea. More useful details on the kinds of things a guy in this position might do to interfere in what is depicted as an utterly corrupt local government. But on his way out, he provides one of the few honest people left in town with all the ammunition he’ll need to clean it up. Port can be brutal, but like Beaumont, he doesn’t kill anyone, even if sometimes his choices lead to deaths.

Kill The Boss Goodbye: Maybe the best of these books as a book, but Rabe cunningly reverses the polarity, making it much more about the boss than the flunky. Cripp, the Beaumont proxy, has never really had an identity of his own, in spite of some extraordinary gifts–his withered leg is symbolic of a withered soul. His employer and friend, Tom Fell, has had a breakdown, and as a friend, his duty should be to get Fell the professional help he needs. As his aide de camp, it’s Cripp’s duty to get Fell back to the trenches before a conniving subordinate takes over. Fell rises to the challenge, then falls before his own maddened hubris. Cripp presumably falls with him. We never find out, because it was never really about him–he was just along for the ride, because that’s his karma. There’s a woman, Fell’s wife, who is the only thing holding Fell together–she’s not the cause of his downfall (that would be Fell himself, hence the name), but in the end, her love isn’t enough to save him either. Cripp would probably kill for Fell, but it never comes up. Horse-racing isn’t that violent.

Murder Me For Nickels: The first of these books to be written in the first person. Also the first (and only) to approach the material humorously, and therefore does not feature a single dead body, though it makes up for that lack with lots of lusty guilt-free extramarital sex. (One might wish this approach were more prevalent in the genre.) Jack St. Louis feels both loyalty and friendship towards Walter Lippit, but he still puts himself first in a pinch, seducing Lippit’s girlfriend (and she him), maintaining a business of his own on the side–he nearly goes down because of the girlfriend’s wounded pique, but she’s also the one who intervenes on his behalf. When they become a couple, there’s no real hard feelings in either direction, but (in keeping with the original) the friendship and partnership with Lippit is over. Probably goes into greater detail about what somebody like this does on a daily basis than any of the other books, but you don’t need to corrupt a whole lot of people to have a jukebox monopoly in a small town. Jack’s a brawler, but he never even thinks about killing anyone. (He hates guns, and as a general rule, none of these guys makes a habit of carrying one.)

We know for a fact Westlake read The Glass Key, and all three Rabe novels (the last one probably after he penned his own duplicate, also in the first person). Seems likely he’d have at least scanned Cain’s novel–very influential crime novelist who didn’t write all that many crime novels (and this one got turned into a movie full of red-hot redheads).

The question mark is Devil On Two Sticks, since I don’t know that Westlake ever mentioned Wade Miller. The marked similarities between that book and this one we’re looking at now could be coincidence, but it would be a lot of coincidences. I’m pretty sure he’d come across it. There’s talk in that book about the organization moving into narcotics, and Beck’s against it. This bush league California syndicate is connected to the Mafia (never mentioned by name), but other than a few lower-ranking guys of Mexican or Filipino ancestry, it’s seemingly all WASPs. They meet at the boss’ house for cocktails and light sophisticated conversation. The Sopranos it ain’t.

Westlake’s goal wasn’t documentary realism (unlikely an Italian American mobster in Gotham is going to have some upstater named George Clayton as his second-in-command, though I suppose stranger things have happened). But one decision he made early on was that it would be set in a real city–New York–and that organized crime would be depicted as Italian-run, and up to its neck in the heroin trade (which is a prime mover in the story–their supplier is in Europe, and if they lose that connection, they lose their power–and then their lives.)

This is a noir whodunnit with an organized crime angle, written for Random House’s hardcover mystery imprint. Which means there’s going to be a corpus delecti at the center of the story, and we’re going to spend most of the book finding out how it got there, and the solution to that puzzle will be the denouement. Since this is Westlake, it won’t be the real point of the story. The point is identity, like I said the last time I reviewed it. But that’s not saying the half of it.

My original review, which I just reread, covered the bases pretty well, considering. I even caught the similarity between Clay and Daniel Port, since I’d read a lot of Peter Rabe novels by then–but I hadn’t read The Glass Key, the template from which all these books came. The Master Key. And for somebody trying to unlock the mystery where Westlake is going with this, and why, a skeleton key.

So no point in a synopsis here. Let’s talk about what makes this duplicate different from all that came before.

The setting is New York City–not some fictional burg out in the middle of nowhere, and not the little-known National City, a short drive from San Diego, which Wade Miller used. The very epicenter of western civilization and the world economy then, and to some extent still today. The cities in most of the other books don’t feel quite real, because they’re not. Doesn’t mean the other writers were wrong–sometimes you want that kind of complete control over the locale that comes from inventing it. But not always.

The protagonist is George Clayton, known as ‘Clay’ to his colleagues. Raised upstate, like Westlake. Did a short stint in the armed forces like Westlake. Went to an upstate college on the GI bill, like Westlake. Got into trouble with the law, like Westlake–but worse. Ran over a young waitress on a deserted road, while driving a car stolen as a prank. Crime boss Ed Ganolese happened by, and more or less on a whim, helped him get rid of the evidence, coached him on how to avoid paying the price for his mistake.

Nobody could prove he’d killed the girl, but he knew he had, and so did everybody else, and he got the cold shoulder, even from his dad. Feeling like Ed was the only one on his side, he eventually came across him again, and asked for a job. It only took him a few years to work his way up from the bottom to be Ed’s right-hand man, described in the papers as a trouble-shooter. That was nine years ago–he’s 32 now.

This is quite different from all the other books (especially Hammett’s), where the fixer’s past isn’t really gone into, where he’s only held the job for a year or two (and yet performs it with practiced skill), and where his loyalty (if any) to the boss is never explained very well. Westlake goes to a lot more trouble with motivation than the others. He doesn’t want Clay to be a mystery to us. There are a lot of speeches in the book where he explains himself (maybe more than there should be–overcompensation–Westlake cared a lot about character motivation, but needed a few more books to learn how to get it across without hitting us over the head).

Like Murder Me For Nickels (which only came out a few months before The Mercenaries), it’s Clay telling us his story in the first person. The others all had third person narrators, though Hammett’s never leaves Ned Beaumont’s side for a moment. In some of the other duplicates, the POV switched around a bit. Not here.

Women are important in all these books, but mainly as a way of telling us things about the men. Ned Beaumont likes women, and they him, but there’s always this offhanded diffidence about the way he treats them. He can take ’em or leave ’em alone, but they refuse to let him alone. He eventually leaves with one, but it’s pretty hard to buy that he’s in love with her. She’s just the next best thing to his friendship with Madvig, which ran its course.

In Cain’s treatment, the fixer (now boss) gets caught between two sisters–using one for her connections, and then falling head over heels for the other, which is always a terrible idea, but never having been in love before, he didn’t know how it can turn your priorities upside down.

In Wade Miller’s book, the fixer falls for the daughter of a colleague, much younger than himself, and she falls for another member of the gang, closer to her age. This has a devastating impact on him, emotionally. He’ll never believe in himself the same way again, and he can no longer control his emotions–which lead him to walk away from the organization, after doing something really noble. And a bit stupid (as noble deeds often are), but we’re given to understand he’ll be okay, if not too happy.

The way of a man with a maid was a Rabe specialty–happy endings not so much. Daniel Port finds true lust with a Mexican American girl, but perhaps because he’s got to remain single for as long as the series lasts, he’s leaving town in search of her at the end, and far as we know he never found her. He finds many others, but if he ever finds The One his story is over, because that seems to be all he cares about (big switch from Beaumont). Cripp seems to have no interest in women, or figures they’d have no interest in him, even though he’s a good-looking guy from the waist up. Jack St. Louis is the biggest ladies man of the bunch, hooks up with two bountiful brunettes during his book, but he never has much in the way of serious conversation either of them–just banter, as a prelude to sex. (Could be talk is overrated).

Ella, Clay’s girlfriend of a few weeks, a nightclub dancer who he asked right away to shack up with him, is depicted as the ultimate male fantasy–smart, serious, sympathetic, and sexy as all hell. Unconvincing, being utterly without flaw–but that may be the point. Clay has to make a choice, and Westlake wants to make the stakes clear. If he can turn this girl down–since she wants him to go straight, or at least go solo, cut the cord to Ganolese–then he’s got no excuse. Life made him an offer, and he turned Life down.

And this is why she’s much more central to the story than the other women in the other books. Even though some of the others were more accurately drawn. She’s Clay’s conscience, and he’s going to talk to her a lot, and listen to her, and be troubled by what she says to him–and what she doesn’t say–that she can’t accept what he does for a living. She knew he was a mobster when they first got together, but she didn’t understand the full implications until later.

Because, you see, part of that living involves dying–murdering anyone Ed Ganolese points at. Sometimes just hiring a pro, but in some cases, the job requires the personal touch. At which point, Clay tells both her and us, he turns off his emotions and becomes a machine. He’s talked to professional killers while engaging their services (Westlake is drawing heavily on Rabe’s influence here), and he says one of them told him he didn’t see how anyone couldn’t enjoy killing. He disagrees.

It’s an easy thing to take your own private sickness and claim everybody else has it too, so it really isn’t a sickness after all. And who could tell this guy, if he were still alive—the cops got him, finally, when he was enjoying himself so much after one job he couldn’t bring himself to leave the body—that he’s wrong, that the sickness is real, and almost exclusively his own?

A guy who’s never killed can’t say whether killing is enjoyable or not. I’ve killed, so I can refute that madman. I’ve never killed a man I hated. I’ve never killed a man who was doing any good for society in being alive. I’ve never killed a man for personal reasons of any kind.

I’ve killed. Only a few times, but I have killed, and I’ve never enjoyed it. It’s been strictly business, strictly a job I’m supposed to do. And I know if I let any emotion come out at all, it wouldn’t be enjoyment, it would be pity. And then I wouldn’t be able to do it.

What I do enjoy is the reputation I’ve got. Ed knows all he has to do is point a finger and say, “Clay, that guy has to stop breathing, don’t farm it out,” and he knows the guy will stop breathing, and I won’t farm it out to one of the professional triggermen, and I won’t do a sloppy job of it. The law has never come near us for any killing I’ve done personally.

That’s part of the reputation. Dependability, no matter what. I enjoy knowing I’ve got that reputation, and I enjoy knowing I deserve it. The other part is that the people in the organization who know me, or know of me, know I’m the best damn watchdog Ed Ganolese has ever had. They know I can’t be bought, they know I can’t be scared, they know I can’t be outfoxed. They know I can turn emotion off, and they know no man has ever been trapped except through his emotions.

Unlike Beaumont and all the others in this key chain I’ve been examining, Clay has committed multiple murders, in cold blood, before we ever met him, and if that bothers him, he does a good job hiding it. Not good people, to be sure, but that’s just because Ed never asked him to kill any good people. He tells Ella that if Ed pointed at her, he’d do it, even though he’s in love with her–this is how he first tells her he loves her–and she sticks around–you see what I mean about the unconvincing part, right?

Hammett and the others didn’t feel comfortable with making an unapologetic killer their hero, for reasons both personal and commercial–that ‘conventional morality’ that Boucher refers to in his review of Westlake’s book is hard to shake, even in crime fiction. But for Westlake, this is not something to be shied away from, danced around. This is a story about organized crime–Ed Ganolese isn’t a corrupt ward-heeler, but a mafia don, albeit with some influential friends in city government. Making people who are in some way complicating your business disappear is part of that business.

Even if there are fixers out there who never bloody their own hands–and there are–or never hire a killer–because that’s a lot easier to get away with in fiction–what difference does it make? You know who you’re working for. You know what the job is. You’ve chosen your loyalties, and right and wrong don’t enter into it. If the boss tells you to make some blonde he slept with go away, and you hire some tough to lean on her, and her baby daughter is there in the car when he leans, and then you pay her off, shut her up–is that better or worse than personally whacking a fellow crook, who’d gladly do the same to you? I guess we could argue the point. I guess we will, someday.

Ed Ganolese himself is different from the other bosses in the other book. We don’t see a lot of him–he’s mainly a voice on the phone, or a brief presence here and there, telling Clay to go find that cutie who set up Billy Billy Cantell for the murder of Mavis St. Paul, and (like Steven Beck, in Wade Miller’s novel) deal with him personally.

We learn about him through Clay, but because Clay is loyal to Ed–feels that he owes him for getting him out of an accidental homicide rap, then giving him a shot that led to his current cushy mobbed-up lifestyle, when he could have just been some ordinary schmo, working a dead end job–because Clay’s identity is all wrapped up in serving Ed–to the point where he knows if Ed goes down, he’s probably going with him–we get the feeling he’s not one of your more reliable narrators, at least where Ed is concerned.

Ella was right, I did like working for Ed Ganolese. I liked everything about it. I liked the feeling of being Ed Ganolese’s strong right arm. I was high enough in the organization so that no one in the world but Ed Ganolese could give me orders. At the same time, I wasn’t in a position of final authority, where the power-hungry boys would like to rush me to the graveyard so they could take over. It was a safe and strong position, one of the safest and strongest in the world, and I liked having it.

That’s not Ned Beaumont, who doesn’t really seem to like his job much, good as he is at it. Ned, a born loner, just likes having a friend he’d do anything for, and he likes being part of his friend’s family, having dinner at the house with Paul’s saintly silver-haired mother, being treated like he’s Madvig’s old army buddy or something, and he just takes all that for granted, until suddenly he doesn’t, and we never really see the process by which that happens.

That’s not Ben Grace, who despises his boss, and can’t wait to backstab him. That’s not Steven Beck, who could care less about his boss, or his position in the organization (which he could walk away from at any time), but is just in love with the idea of being good at his job. It’s not the conflicted rebellious loyalty of Dan Port (who is dead determined to quit for the entire novel, but just when he thinks he’s out….), the blind loyalty of Cripp to Tom Fell (that destroys them both), or the cunningly conditional compartmentalized loyalty of Jack St. Louis to Walter Lippit, while still looking out for his own private interests, and screwing Lippit’s girl when he’s not looking.

George Clayton has just decided to define his identity through his loyalty to the man he works for. He feels no great love for the guy. They don’t socialize (that’s bad business). He doesn’t go to dinner at Ed’s house. It’s 100% professional, and well-compensated as he is, unshakeably loyal as he is, Clay doesn’t think of himself as Ed’s friend. He thinks of himself as Ed’s servitor. His good right hand. Ed uses the phrase himself. He’s all-in for Ed–but it’s strictly one way.

He’s not being groomed for leadership (wrong background, no family connection, unlike Ray Kelly in 361.) Which is fine by him, because he doesn’t want to be the boss. And in spite of Ella’s remonstrations, he doesn’t want to be his own man either–take responsibility for his life, his choices. And that, for Donald E. Westlake, is the unforgivable sin.

Most of the book is Clay dutifully following the trail, interviewing suspects like a cop (he’s painfully aware of how funny this is), crossing names off the list one by one, until he’s got the perp. It’s well done for what it is, but the real point is to see how smart Clay is, how perceptive about other people–and how blind to himself.

That crack he makes about that hired killer pretending everybody else has the same problem as him–he’s doing the same thing all through the story. Over and over, he insists that we’re all crooks, in one way or another. Nobody’s honest, nobody’s clean, everybody’s got an angle. He makes a persuasive case–but for the wrong reason. Not to see himself more clearly, but to avoid seeing himself at all. He tells Ella all about what he does, who he is, because he wants her to be with him, not some image of him she’s invented in her mind–but she sees him more clearly than he ever will.

“As a cop told me tonight,” I said, “I work within the system. Guys like Ed Ganolese, and the organizations they control, exist only because the average citizen wants them to exist. The average citizen wants an organization that can supply a nice, reliable whore when he’s in the mood. The average citizen wants an organization that runs after-hours drinking places for the nights when Average Citizen doesn’t feel like going home at closing time. The average citizen likes a union that’s a little crooked, because he knows some of the gravy’s going to seep down to him. The average citizen even likes to know there’s some place where he can pick up some marijuana if he feels like being wild and Bohemian for a while. And with the number of drug addicts in this country numbering over a hundred thousand, I’m talking about the average citizen. The average citizen also likes to gamble, to buy his imported whiskey cheap, and to read in the papers about desperate gangsters. The average citizen votes for crooked politicians and knows they’re crooked politicians when he votes for them. But maybe he’ll get something off his property assessment, or he’ll be able to pick up a little graft. At the very least, he’ll get his kicks by knowing somebody else is picking up some graft.”

“That’s all rationalization, Clay, and you know it,” she said.

“It isn’t rationalization, it’s the truth. It’s the way the system works and the reason for the system’s existence, and I work within the system.” I got to my feet and paced back and forth, warming to my subject. It was a subject I’d thought about often during the last nine years. “Simple economics shows it’s the way the system works,” I said. “Look, no business can survive if it doesn’t get support from the consumer, right?”

“Clay, this isn’t a business.”

“But it is. We don’t rob banks, for God’s sake. We run a business. We have items for sale or for rent, and the goddam general public buys. Girls or drugs or higher wages or whatever it is, we give something for the money we get. We’re a business, and we wouldn’t last a minute if we weren’t supported by our goddam buying public.”

And that’s true. Maybe more today than it ever was. And maybe there’s nothing anyone can do about it, but there’s something anyone can do something about–and that’s himself. Clay talks a good game about how other people kid themselves, but he’s the biggest kidder of them all. Because he believes as long as he’s loyal to Ed Ganolese, Ed Ganolese will be loyal to him.

That was the crucial assumption in The Glass Key, and it’s the central flaw of that book. Beaumont never betrays Madvig, no matter what the inducement. Madvig only betrays Beaumont by withholding crucial information, for what would have to be called unselfish (if irrational) reasons. Ned Beaumont is a fantasy figure with a credible world-weary edge to him, and nobody did those better than Hammett–but Madvig is pure fantasy. He doesn’t exist. Not in that job. Not for very long. And the novel founders on that problem. Okay, not everyone agrees with me about that. But I can think of five capable mystery authors who did.

All the writers who tried their hand at fixing Hammett’s mistake came back to the relationship between fixer and boss. Why would someone so much smarter and tougher than the man he works for go on working for him, when the price is so high? James M. Cain said he wouldn’t–he’d take the power for himself. Wade and Miller said he only cared about doing his job well, and the fixer job was more interesting. Peter Rabe said one was trying to repay an old debt before he made his exit–another had no self-esteem, needed an idol to worship–a third was just biding his time, delaying maturity.

Donald Westlake said what Shakespeare said before him–the fault is in ourselves. That we are underlings. Whether we follow the leader blindly, or blame him for our problems–either way. We’re not taking responsibility. We’re failing to know ourselves. And that makes it inevitable that bosses will come–and they won’t be any great geniuses. Like Ed Ganolese, who makes a critical mistake at the end, and (it is strongly implied) sets up his good right hand to pay for it–they are ruled by their own chaotic emotions.

It’s interesting to me that Westlake didn’t let Ed get away with it. He wrote a much better novel than this, not long afterwards, about a better man than Clay, who does come to know himself–and Ed Ganolese has a brief cameo in that novel, where he meets his own end. Doesn’t even get any lines. And when the trigger is pulled, you know it’s Westlake pulling it. And I like to think that was also Westlake’s subtextual homage to Wade Miller’s book, since Pat Garland’s downfall is reported to us in an unrelated detective novel. Westlake did it better. Westlake almost always did it better. We should remember (and he never forgot) that he stood on a lot of shoulders while doing it.

Did he this time? Is this the best of the duplicate keys? Is it better than even the Master Key?

Yes. No. I don’t know. Does it matter? Do we really read fiction only to rate it? And shouldn’t we rate it most of all by what it teaches us?

Reading this book for the fourth time (Fifth? Lost count.), I was reminded how not good some parts of it are. Westlake was maybe halfway to finding his voice as a writer. Parts of it are startlingly sharp and on-point, even today–which only clashes the more with the parts of it that are too by-the-numbers. The contrivances you can’t avoid in a story like this (or any story) are not well concealed enough.

Too many well-worn genre clichés that he hasn’t quite yet mastered the gift of making his own. Too many stock characters who don’t quite come to life. Ella is more than a mere sex interest, though there’s a lot of (sadly offscreen) sex, and we’re very interested–but she’s less than a fully developed person, a problem Westlake would have over and over again when he idealized women, as he was wont to do at times (his best women were crooks, just like his best men.) A few too many impassioned self-explanatory speeches by Clay, though it was crucially important to Westlake that he get his points across–while we infer all the points left unmade. The soapbox was another thing he’d learn to conceal better over time.

Of all these noirish narratives, only The Mercenaries is a first novel (well, first novel that isn’t pseudoporn cranked under a pseudonym). I think each of the previous books is better, each in its own way–and worse, ditto. I think that’s the story here. That each writer found his own answer to the question posted by Ned Beaumont and his duplicates, and no answer could ever be perfect, because Hammett’s original pattern was flawed, if intriguing. The key always shattered in the lock.

But for all that, I would say the door opened a little wider each time, even if the chain stayed on. Life has certain unifying patterns, just like keys do. But it’s the variations in each new pattern that make the difference. That create the possibility of a different ending to the same old story. That make us individuals. When the bosses in this world just want us to be machines they can use and control. But we can walk out on them. Or overthrow them. Or become them. Or remain loyal to them. And see where that gets us.

I wonder about Clay. After all this time. He’s sitting there in his living room, having sent Ella a message they’re through. He let himself get emotional about her, and he can’t afford that. But as he goes over recent events in his head, he’s recognizing that Ed made a stupid emotional blunder, that the cops will capitalize on–they’re going to need another fall guy. Then the doorbell rings. It’s probably that nameless call girl he ordered, to help him forget Ella, and all her niggling little questions. But what if it isn’t? What if he had it figured wrong, this whole time? What if he’s the fall guy?

Even now, he’s still got a choice. We’ve been told there’s a fire escape. He can use it. He can run to the club, tell his beautiful conscience he’s sorry, she was right all along, and they make a run for it together–or he can turn state’s evidence. The odds of either path working out are lousy. But his creator gave him that escape hatch on purpose. So he’d have the chance of at least going out his own man. Instead of a pathetic patsy. That’s one chance we all get in life. For all the good we make of it. God Save The Marks.

Boucher got one thing wrong in that review. It’s not conventional morality. Clay isn’t doomed because he’s a crook, or he murdered somebody in cold blood. He’s doomed because he’s murdered himself in cold blood. Alternate morality. Something Donald Westlake (and Richard Stark) would become known for in a lot of much better books coming down the pike.

See, one of the undoubted pleasures of crime fiction is that it gives us an escape from our humdrum lives–a chance to immerse ourselves in a world where the rules and guilts and fears that run our lives can take a backseat for a few hundred pages. Westlake is writing about himself and his fellow crime writers, as much as Clay, when he puts that speech in his mouth about how us law-abiding folks love to read about criminals, identify with them–as long as we don’t see our own pockets being picked. (They are, of course, we know full well–just don’t let us see it.)

What made The Glass Key special for Hammett, I think, was that he was doing something different from his other books–instead of bringing law-abiding readers into a criminal underworld, he was bringing the criminal underworld into the world of law-abiding readers. He could have done a better job of it, and one of the things those who followed his lead were doing was trying to better fill in that gray area he created, inhabited by the fixer and his boss–straddling that fence between lawless and lawful.

Westlake did more than that–he had his protagonist suggest the law-abiding world itself is an illusion. That we’re all crooked, all on the take, all part of a criminal underworld–and as Clay tells the Puerto Rican kid who parks his car for him, and wants to join the Ganolese mob, “It’s not what you think it is, kid.”

I’m guessing some I know who like this book more than I do (and I do, just not as much) are reacting to this honesty, vis a vis dishonesty. And the escape hatch it gives them. But they’re missing a crucial point. Clay is right in a general sense. We’re all crooks in some sense. But it’s the specific sense that kills him. (Unless he found his own escape hatch.) The creator of Parker and Dortmunder didn’t damn this early prototype for being a crook. He damned him for being a tool.

Even if everybody around you is a crook, that doesn’t prove you have to be one–even if you are literally a crook, that doesn’t mean you have to work for bigger ones. You still get a choice, every day, to go a different way. And you’re responsible for your choices, whether you acknowledge them or not. The sin is not being a crook, or even an enabler of crooks. The sin is lying about it. “I had no choice” is the biggest lie of all. That’s just stealing from yourself.

Now I said this is the last duplicate key I know of, and in the realm of print fiction, that’s true. But in the realm of celluloid fiction, there’s one more. I’ve seen bits and pieces of it on cable, never watched it all the way through. I’m going to do that now.

And while I do, I’m going to wonder whose sick sense of humor is responsible for the fact that the people crafting this key, imagining yet one more feckless fixer for a boob of a boss were brothers by the name of Coen. (The ‘h’ is silent anyway).

One more time, I am moved to ask–who writes this stuff?

I only wish Westlake did. Holy ghost-writer? We can but hope.