The death of Johnny Crawfish stunned the civilized world. The thirty-eight year old country singer who had risen from poverty and squalor as the child of migrant farm workers, the gravel-voiced balladeer who had found both God and his muse in a Tennessee prison where he’d been sentenced for manslaughter, the self-taught millionaire songwriter/businessman who by his thirty-fifth birthday had appeared in command performances before both Queen Elizabeth and President Reagan, died that Saturday morning of at first unknown causes in The Shack, his palatial thirty-room waterfront estate on Chesapeake Bay north of Newport News, Virginia, and when the news was flashed round the globe it was as though four billion human beings had just lost their best friend.

What we call fiction today is different from either the history or poetry known to readers before Cervantes’s time. For a prose narrative to be fiction it must be written for a reader who knows it is untrue and yet treats it for a time as if it were true. The reader knows not to apply the traditional measure of truthfulness for judging a narrative; he suspends that judgment for a time, in a move that the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge popularized as “the willing suspension of disbelief,” or “poetic faith.” He must be able to occupy two opposed identities simultaneously: a naive reader who believes what he is being told and a savvy one who knows it is untrue. In order to achieve this effect, the author needs to pull off a complex trick. At every step of the way a fictional narrative seems to know both more and less than it is telling us. It speaks always with at least two voices, at times representing the limited perspective of its characters, at times revealing to the reader elements of the story unknown to some of or all those characters.

From The Man Who Invented Fiction: How Cervantes Ushered In The Modern World, by William Egginton.

Donald Westlake loved to experiment with the structure of his novels. Rarely did he write a book that was just Chapters One Through Whatever. He split his books–even the short ones–into different parts, with different purposes, and he named them, and you just never knew, opening a new Westlake, how it was going to be laid out.

This book starts off with The First Week, which runs four chapters–the week in question is Sara Joslyn’s first on the the Weekly Galaxy, obviously. The First Day also runs four chapters, and refers to the fact that Sara gets a permanent parking sticker for her car at the end of her first week, and that’s really when she’s a Galaxy employee in full earnest. The First Hundred Years takes up eight chapters, and is meant to indicate that even though she’s only been there a month by the time it ends, in reality (as with all indoctrination periods) it’s been more like a lifetime. Our jobs tend to change our identities, the daily routine marks us, for good and ill, and it doesn’t take long at all for those changes to be noticeable.

Which brings us to The Wedding, the longest part of the book, a very busy eleven chapters worth of mendacious maneuverings. As we saw last time, having learned that she’s actually brilliant at the job she was initially ambivalent towards, Sara Joslyn, once a strong believer in journalistic integrity and serious news, has been well and truly corrupted by her new job–not by the insanely large salary, the basically unlimited expense account, or even the tender ministrations of her nominal boss and newly minted lover, Jack Ingersoll.

No, she’s just found out it’s really really fun to think up ways to con people, to dream up cunning subterfuges, to obtain unobtainable information about the rich and famous–and get paid for it. Basically a tabloid reporter is a professional grifter/spy, with a weekly paycheck and a presumably excellent healthcare plan. Sara Joslyn, who a short time earlier was worrying about which of her half dozen or so half-finished novels to finish, now believes she may have found her true calling in life.

Jack, watching her rapidly become the the most intrepid scandalmonger the Galaxy has ever seen, worries he may have degraded an idealistic young soul. But he’s so enjoying her idealistic young body. It’s a moral quandary. And here he was thinking he’d left all such tiresome concerns behind in the 1960’s, where they belonged.

So John Michael Mercer, the brooding hunky star of Breakpoint, is getting married to a delightful young woman named Felicia, who is quite simply a doll. Sweet-natured, unostentatiously sexy, low-maintenance, neurosis-free, with nary a skeleton in her doubtless immaculate closet. One would think there would be no story there at all, or at least no story other than “John Michael Mercer got married, sorry girls (and boys who hoped he was secretly gay).”

But it is Mr. Mercer’s misfortune that he is the object of a driving obsession on the part of Bruno DeMassi, the Galaxy‘s pernicious publisher, who owes his success to the fact that he understands his readership on an almost cellular level–he knows what Inquiring Minds Want to Know. (I want to know!)

So ‘Massa’, as his staff only half-humorously refers to him, will not brook any excuses, or set any budget to the single-minded quest of extensively and intimately covering what is supposed to be a strictly private ceremony. He has decided in his infinite wisdom that ‘the story’ is going to be an interview with Mercer, complicated by the fact that only certain pesky laws against bodily mayhem have stopped Mercer from habitually doing to Galaxy reporters what he presumably does to bad guys every week on his show.

So in brief, this is to your typical wedding coverage in the news what the D-Day Landings are to the Staten Island Ferry making its 30th docking of the day (at Staten Island). Think I’m being hyperbolic? Wanna bet?

Jack’s team having won control of the wedding coverage, he, Sara, Ida Gavin, The Aussie Trio, and many others fly to Martha’s Vineyard and set up a command center in a house the paper has rented at obscene expense (hotel rooms being scarcer than poultry dentition). Louis B. Urbiton and Harry Razza are deployed to waylay the other ‘legitimate’ journalists coming in to cover the wedding, and get them all royally drunk.

Bob Sangster has an additional assignment–to pose as Jack Michael Mercer’s cap-tugging limo driver. “I’m just a simple Aussie,” he keeps saying. Simple like a bloody dingo. More brass than a Big Ten University marching band.

“I don’t mean to intrude, sir,” the driver said, with a little stiffening of the shoulders to indicate the distance he knew he was expected to keep, “but if at some point you wouldn’t mind to give me just a little autograph for my daughter, it would be the thrill of her life.”

“Of course,” Mercer said, smiling, while Felicia squeezed his hand.” “What’s her name?”

“Fiona,” the driver said. “She’s your biggest fan.”

“Is she?”

“But we all are, sir, if truth be told. The whole family, we wouldn’t miss a thing you do. Not just Breakpoint, you know, but everything. That blind rodeo rider in the movie for television, Study in Courage, was it? That was beautiful, sir, if you don’t mind. Beautiful.”

“I am proud of that one,” Mercer agreed, nodding in manly acknowledgement.

“Not to intrude, sir.”

“Not at all, not at all.”

You feel kind of sad when the vigilant staff of the exclusive hotel the happy couple are staying at, find Bob out, beat him to a pulp, and show him the door. Fortunes of war, mate.

The Galaxy‘s next move–which both shocks and thrills Sara, increasingly aware of just how much power and money her employer has to throw around when the situation warrants–is to moor a world-class yacht, the Princess Pat, within sight of the hotel, and inform Mr. Mercer that in exchange for his agreeing to an interview, he and his intended may sail off on it, anywhere they please (what do you suppose the odds are there would be no hidden cameras and listening devices installed onboard?). Mercer is still not allowed to shoot anyone in real life, even in Martha’s Vineyard, so he just says “No” and slams the door in the messenger’s face.

At this point, Massa must acknowledge that ‘the story’ will not be an interview with John Michael Mercer, so it will have to be the wedding album. Pictures. Exclusive to the Galaxy. By any means necessary. And as always wishing to set his reporters at each other’s throats, he tells Jack’s eternal nemesis, the smarmy Boy Cartwright, to go there and get those pictures. Boy departs with all due alacrity.

Sleeping off a spate of drinking brought up by the aforementioned fortunes of war, Jack and Sara hear shots fired outside Jack’s motel room. Turns out they were fired inside Sara’s vacant motel room. Into Sara’s vacant bed. Unclear if this is a real murder attempt or a very stern warning. Jack manages to conceal Sara’s presence in his room, since the Galaxy (if you’d believe it) will not brook any moral turpitude from its staff. Now the police have to actually go interrogate John Michael Mercer, to make sure he didn’t actively follow up on one of his innumerable threats towards the Weekly Galaxy and all those attached to it. He didn’t, of course. But now things are really getting out of hand.

The war is going against Mercer and Felicia, in spite of the valiant efforts of the hotel staff–there’s always somebody on the staff who can be bribed. The manager is sadly forced to admit that he won’t be able to guard their privacy, but being a throughgoing professional (something Donald Westlake appreciates deeply in all walks of life), has a back-up plan.

The couple can stay with Lady Beatrice Romney (no relation, I’m sure), widow of an English general who was forced to leave that more happier land under a cloud after his military bungles led to the Dunkirk evacuations (the most glorious retreat in all of history). A new Romney Hall, with grounds quite capacious enough to hold the ceremony, has been constructed in Martha’s Vineyard, where Lady Beatrice still broods on the iniquities of the British gutter press which hounded her late husband to an early grave. No, I don’t believe a word of this either, and I don’t give a damn, do you? Rarely have I suspended disbelief more gladly.

Hearing that a fellow subject of Her Majesty is now the person to approach, Boy figures he’s got the inside track to nab those wedding photos. Yes, you see where this is going. But the thing is, Boy doesn’t. Been away from home too long. Forgot about the class system.

“Well, he says he’s from a newspaper, Mum,” Jakes said, with a faint but unmistakable edge of disapproval. “He says he’s from the Weekly Galaxy, Mum, it’s a sort of servant-girl paper, all in color.”

Lady Beatrice’s eyes glinted. So the villainous press had traced the fair couple, had it? Well, it would not be permitted to destroy their happiness. “And the scamp,” she said, “has the effrontery to come to my front door?”

“He asks if he can have a word with you, Mum.”

“Put the villain on.”

“Boy Cartwright here, Lady Beatrice,” said the villain, and the instant she heard that glutinous voice, that style of Uriah Heep after assertiveness training, Lady Beatrice placed the fellow precisely and unerringly in his proper pew in the great English pecking order. A tradesman’s son from somewhere like Bradford, a redbrick university dropout, the sort of fellow who in Manchester or Liverpool sells used cars to Pakis. “If I could have a bit of a chat, Lady B,” this mongrel said, “I’d be most appreciative.”

You’ve had your bit of a chat, my lad, Lady Beatrice thought, and said “Put Jakes on.”

“I beg your pardon?”

“That large strapping fellow there with you. Jakes. Put him on.”

“Oh, of course, of course. See you in half a tick, then,” the creature said, and Lady Beatrice heard him, away from the phone, say snottily to Jakes, “Your mistress has instructions for you.”

Oh, that she does, my lad. Let us avert our eyes from the distasteful events that follow, involving a large leather belt. At least she didn’t say ‘release the hounds.’ Later on, she does, in fact, release said hounds, but we’ll get to that. A great pity Dame Edith Evans could not be cast to play Lady B.–certain tonal inflections only she could do to complete perfection. I rather suspect her Lady Bracknell in the 1952 film version of The Importance of Being Earnest was in Westlake’s mind when writing this scene–but of course she’d gone to her final reward over ten years before this book came out. Hopefully they have plenty of cucumber sandwiches there, and I trust no journalists of any kind.

These scenes at Romney Hall are written very much from the perspective of Lady Beatrice and her two young guests, who she takes an immediate liking to–somehow, all aristocrats understand each other, and what else are celebrities but modern aristocrats? John Michael Mercer starts reverting to the courtly western accent of his boyhood, accentuating it to the point where he might as well be doing Gary Cooper. He positively beams when Lady B. mentions her late husband’s frequent avowal that all reporters should be horse-whipped on sight. And you fully sympathize with them, identify with their perfectly sane and understandable desire for privacy, and you want them to win out against these ruthless ink-stained sewer rats.

And then you switch back to Jack and Sara, who are themselves such a fine couple, so brave and resourceful and determined to get the personal data the great unwashed who constitute their readership demand as their rightful due for making Mr. Mercer rich and famous and privileged beyond all belief, and you’re right back in their corner again. And this is intentional. Westlake is pitting our divided sympathies against each other, forcing us to think about the underlying realities that make up our confused modern world.

A bit earlier in the book, Sara, frustrated beyond all endurance by the obdurate refusal of Mercer to allow them any access whatsoever to his personal life, speaks for all us inquiring minds–and we’re a bit embarrassed by how well she does it. Ida asks who the hell Mercer thinks he is (well he’s an actor, so obviously it depends on the script).

“That’s right,” Sara said, as fierce in her own way as Ida. Jack stared at her in ambivalent surprise–did he want Sara to become Ida? What a thought!–as the girl shook her fist and declared, “What do people like John Michael Mercer have, except their celebrity?”

“That’s right,” Ida said, glaring at Sara in aggressive solidarity.

“And where do they get their celebrity?” Sara demanded.

“From us,” Ida snapped.

“That’s right!” Sara cried, in full voice. “When they want publicity, we give it to them. And when we want, they’ve got to give!”

(Westlake used the the pithy declarative phrase “that’s right” perhaps more than any other writer I can think of, but not even in a Parker novel did it ever occur so many times in so short a passage. Does this mean he thinks tabloid reporters are harder cases than bank robbers? Hmm.)

Jack’s own identity crisis, relating to Sara, is now in full bloom. He’s increasingly seeing her as his own perky blonde Frankenstein’s Monster. And with her sleeping in his arms, he lies awake, trying to puzzle it out. Is he having–feelings?

With what trouble and difficulty Jack had rid himself of extraneous emotion several years ago he could barely stand to remember. A thoroughgoing romantic in college and beyond, slopping over with empathy and fellow-feeling, as naive as a CIA man at a rug sale, he had been hardened, annealed, by circumstances too harrowing to store in the memory banks, and since that time he had been safe.

It had been a conscious decision he had made, four years ago, to retire from the human race, to care about nothing, to become as self-sufficient as Uncas. He had chosen deliberately an environment where emotional attachments of every kind from the greatest to the smallest, were literally impossible. It was not conceivable to care for one’s fellow workers at the Galaxy, for instance. One amusedly pitied a Binx Radwell about as meaningfully as if he were a puppy with a thorn in its paw; one used an Ida Gavin and then washed one’s hands; one rather relished a Boy Cartwright as so thoroughly representing the environment.

Equally, one could not become emotionally involved with the job. Not this job. Nor could one care about the pip-squeak transitory celebrities on whom they all lived their parasitic existence. Even the state of Florida helped; anyone who managed to sing the glorious rocks and rills of that sunny buttcan needed psychiatric care.

Too thoroughly burnt-out a case even to relish the romantic self-image of being a burnt-out case, Jack Ingersoll had retired to Florida and the Weekly Galaxy and the likes of Ida Gavin and Boy Cartwright to lick his wounds and care never again about anything at all. Not even possessions; his Spartan life not only gave him more money to put into blue-ribbon investments, the better to prepare for that inevitable day of involuntary retirement, it also kept him from falling–like puppy Binx–in love with things. He who has nothing has nothing to lose. And he who has nothing to lose has already won.

Except, Jack realizes with bewilderment, looking down at the sleeping blonde head on his chest, he has everything to lose now. And he doesn’t have to break up with her to lose her. He can lose Sara by Sara ceasing to be Sara. And then what is he? And that’s romantic attraction in a nutshell. An identity crisis within an identity crisis. Because Sara is only doing all this to prove herself worthy to him. And he’s proud of her. And ashamed of himself for being proud of her. Ain’t love grand?

So finally, all gentler stratagems having failed, the order comes down from on high–STORM THE WEDDING. An all-out nuptial assault, by land and sea and air. And you think Westlake is making this shit up? Google pictures of Madonna and Sean Penn’s wedding, if you get the chance. Coming back to you now? Yes, I know they’re both stuck-up assholes, and that marriage had about as much of a future as Betamax VCR’s, but still.

Sara leads a cavalry charge–on horses rented from a riding stable. Boy leads a naval assault, a small flotilla of boats attempting to unobtrusively mingle with the vessels belonging to members of the Mercer wedding. And Ida takes command of a helicopter bristling with long lenses, the heavy artillery of the paparazzi.

And all for naught. If only Lady Beatrice had been leading His Majesty’s forces in spring of 1940, instead of her late husband (unkindly dubbed The Dunce of Dunkirk by the aforementioned gutter press), there wouldn’t be nearly so many WWII movies and documentaries. The attack is beaten back on all fronts, with no loss of life, but considerable loss of dignity. Clubs are brandished. Non-metaphorical hounds are released. Pants-seats are ripped. Riders are thrown. Shotguns are fired. The helicopter pilot has PTSD from Vietnam, and gets the hell out of there. Napalm regrettably not an option.

All is lost. No usable photos. They have an interview with the minister who performed the ceremony–in exchange for them publishing his treatise on how to solve the Northern Irish Troubles–send the Protestants to Mars–not entirely without merit, but not nearly enough to satisfy Massa and the readership. They mussed the bride’s hair up a bit with the backwash from the helicopter, made her lose her veil, made her cry. Oh good for them. A hard-fought victory for John Michael Mercer and his blushing bride, but victory all the same, as the happy couple kiss, and are seen no more in this book. “Bastards,” Sara says, gazing upon them with hatred. “Bastards, bastards.” That’s the spirit.

And that defiant indomitable spirit simply will not allow the possibility of defeat. Sara’s gift for lateral thinking comes into play once more. Lady Beatrice took the wedding photos herself, being an accomplished amateur photographer. And where do amateur photographers get their photos developed? Back in the days when photos still needed to be developed? The drug store. She finds out which one. She picks up the photos herself, claiming to be doing so for Lady B. The Mercer wedding album is presented to a delighted Massa. The forces of evil have triumphed after all.

And in appreciation of this magnificent service performed on behalf of Vox Populi, Jack’s team is given a Body in the Box assignment. In Part Five of this book, which is predictably entitled The Body in the Box. Sara has been hearing this phrase repeated over and over throughout the book, and she’s been afraid to ask what it means.

It means you have to get a photo of a dead famous person in his or her coffin. The family of the deceased typically objects to this. But certain disreputable members of that family (and what famous person in all of history did not have disreputable family members? what person, really?) can often be bribed to provide a covert snapshot, of generally execrable quality, but that’s not the point.

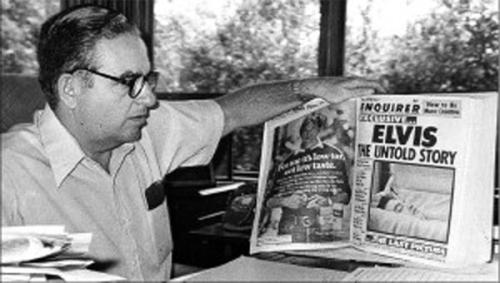

No, the point is that The People demand to see their idol’s decomposing corpse, perhaps merely to reassure themselves that if Life is not fair, Death is nothing but. You see those photos up top? This is still very much a thing, people. And will remain a thing as long as people keep buying the papers containing these photos–and then buying reprints of them (the National Enquirer has been reprinting that Elvis issue for decades now).

So the dead famous person is country music legend, Johnny Crawfish, and this is where we came in. So let’s cut to the chase, shall we? Sara, not so much a reluctant detective as an absent-minded one, has completely forgotten about the murder mystery. The murderer has not. The murderer is a Galaxy reporter. The murderer intends to shut Sara up for good (even though she’s basically given up trying to solve the mystery) .

Sara and that same killer who now intends to kill again have entered The Shack under cover of being from the Virginia board of health, because (they say) Johnny Crawfish’s corpse has AIDS, so all non-essential personnel must be evacuated, so now they can take all the photos they want. Yes, this is in terrible taste, most insensitive, and I bet it would have worked if somebody had actually tried it back then. In the rural south, definitely. But quite possibly anywhere.

This is a terrific book, make no mistake, but I doubt there’s anyone who reads it who doesn’t have a pet peeve. Here’s mine. Sara was the detective here, distracted though she may have been. Westlake typically put his amateur detectives (all of them guys, up to now) in a position where they had to solve a murder mystery to save their own asses. And they invariably do so, and get to explain to all present not only whodunnit but how and why it was done, and they’re always right. Because that’s the genre.

This is not really a mystery novel, but it has a mystery in it, and Sara is the detective. She did all the legwork (and she has much better legs than all the previous Westlake detectives). And she not only does not figure out who the killer is until it’s very nearly too late, but having survived, she lies there in a gurney, in a state of shock, while Jack, who has raced to the scene of the almost-crime, after belatedly realizing he’s sent her to her death, tells her what happened, and why.

It works. Dramatically speaking. Emotionally speaking. Jack needed the shock of Sara’s near-death to get him to declare his love for her, and it makes sense he’d be able to put together the pieces Sara had assembled, knowing more about the background of that particular crime. I’m not saying I don’t enjoy the scene, that it’s not very well written. I’m just saying it’s not fair.

Donald E. Westlake was simply not put on this earth to write novels about female protagonists–great female supporting characters, yes. But as the central figure in the story, no. That’s neither a criticism nor an excuse. It’s a statement of fact. Even though he’s put much of himself into Sara Joslyn, even though he’s imbued her with many admirable qualities, even though he was destined to write one more book about her (in which she does solve the mystery all by herself, and Jack is relegated mainly to the sidelines)–his great protagonists are all Americans, all caucasians, all males.

That’s the perspective he was most comfortable with, even though he loved writing from many others, needed to stretch outside of his comfort zone–he still retreats back to it, when all is said and done. It’s not that he’s a man, because many of the most compelling heroines in all of fiction were created by men, quite a few of them before Donald Westlake came into this world. It’s because as is true of all of us, his strengths are bound up in his weaknesses. A package deal.

Sara’s a fine experiment, and since the book does not revolve solely around her, her deficiencies–chief among which is the fact that maybe she’s just a bit too damn cute for her own good–do not detract from the many pleasures of the narrative, which is not about who murdered whom at all. And maybe I’m still sulking a bit that the estimable J.C. Taylor from the Dortmunder novel Good Behavior never got her own book. But a writer is his or her choices, and all writers, even your favorites, make choices you don’t approve of. You live with that, or you read somebody else whose choices you don’t always approve of. Or you write your own stories, and make choices other people don’t approve of.

And his final choice here is to end on a rather deliciously ambiguous note, in Part Six, The Way We Live This Instant. Jack and Sara have achieved a fuller understanding of each other, and of themselves, and they know now they don’t want to waste the best years of their lives together serving the whims of Massa. So they make their way to the offices of Trend (promoted as The Magazine For the Way We Live This Instant), which Sara has previously deemed nothing more than the Weekly Galaxy for people with money.

Armed with certain embarrassing personal data, they successfully blackmail an editor there into hiring them on (this relates to his having earlier tried to do a Galaxy-style story about the Galaxy). And though initially discomfited and angered by this violation of his privacy, the editor decides it’s actually a win–these two sharks will make him look good. And eventually take his job, but hey, that’s the news biz.

And here’s where we have to ask ourselves–the same way we ask at the end of that brilliant fast-paced gender-switched remake of The Front Page that Howard Hawks gave us so long ago, and nobody has come close to equaling since (except maybe here)–have we been rooting for the wrong side?

Sara and Jack have made strides, certainly. They’ve escaped the feudal bondage of the Galaxy, the trap that represented–only to wander into a larger trap. They’re still going to be reporting mainly on things that don’t really matter, to satiate the morbid curiosity of a better-heeled class of readers. They have found love, and material success, and personal empowerment, and all the things that are supposed to matter–but have they lost themselves? In the media-dominated world they–and we–inhabit–is anyone really completely themselves?

So there’s a double-meaning to that ending–the book is on two sides at once, and so are we. And nothing has changed. The Weekly Galaxy is still out there in many appalling forms, and can anyone honestly not look at the media scene we have now, 24/7 cable channels, news blogs that often make the National Enquirer and Weekly World News look positively quaint and old fashioned, and not conclude that Massa is the only real victor here?

And how has he won? By being “an executive who is fond of promoting rivalries among subordinates, wary of delegating major decisions, scornful of convention and fiercely insistent on a culture of loyalty around him.” You know who that quote actually refers to? Guess.

Viva Love. Viva Mystery. Viva Celebrity. Viva Chicanery. And viva Freedom of the Press, seriously. For all its myriad abuses, it’s our best weapon against the plutocrats. But it’s also their best weapon against us. And the war goes on. And Jack Ingersoll and Sara Joslyn are not going to be very helpful to us in that war. They’re too busy enjoying life, and each other. But they entertained us, and taught us a few things about ourselves. And that’s something, surely.