Westlake is the exact opposite of, say, a Stanley Ellin, who writes good novels and wonderful short stories. The Westlake novels are always among the best of the year, the shorts are merely very good–clever, imaginative, ironic, admirably crafted, very much in the Alfred Hitchcock manner, and far more neatly professional than most of that school. I suppose the main difference is that the novels have people in them. Westlake has yet to learn how to make his characters breathe in a short story; but his other virtues are so marked that this may be a niggling objection.

Anthony Boucher, Criminals at Large, the New York Times, March 31, 1968–reviewing an earlier anthology, but might as well have been this one.

You’ll note that the covers of the first hardcover edition of this anthology and the later paperback reprint both feature manual typewriters. Perfectly appropriate to this author, who stubbornly stuck with that method of committing words to paper (and paper itself) to the end of his life. His weapon of choice was the Smith Corona Silent Super–but the first edition clearly doesn’t feature that machine. I rather think the reprint does, but they seem to have removed the brand name (no endorsements). See what you think.

This is probably a twin of the machine he told an interviewer about getting from a warehouse once, after Smith-Corona stopped making Silent Supers–all they had was pink. Like really really pink. He said he gradually managed to de-pink it somewhat, and kept plinking away. So did Smith-Corona, but they had to give up on the typewriter entirely, after a while. They make something called ‘thermal labels’ now and seem to be doing fine. I’m not sure Westlake would have even had the heart to make a joke about that. They have an entire online museum devoted to the noble typewriter, so you know they never really got over its demise either. Speaking as somebody who makes a lot of typos, and hated wite-out with a passion, I’m okay with it. Yet oddly gratified that he wasn’t, somehow.

Westlake wrote quite a lot of short fiction, mostly for magazines, and very little has ever made it to book form. Basically, if you’ve read the very first anthology for Random House in the 60’s (The Curious Facts Preceding My Execution), combined with the linked stories collected in Levine, and the Dortmunder related stuff in Thieves Dozen, you’ve probably read all his best work in that format.

I can’t say this for certain at the present time, since there are many stories of his I have not yet read (I doubt I’ll ever find them all, nor is a definitive anthology ever likely to appear), but I can’t help but notice, when perusing contents of the existing anthologies over at the Official Westlake Blog, that the same small handful of stories (often under different titles) keep cropping up, over and over again. Either there were problems with the rights to other stories of his that merited being collected (and I don’t know why that would be) or else Mr. Westlake only felt like a very small percentage of his small-scale yarns were fit for human consumption. Bit of both, maybe.

(And I have no idea how many of his shorts have appeared in general mystery anthologies involving multiple authors. Westlake helped compile one of those himself, and guess how many of his stories he put in it? That’s right. Well, it would have looked bad if he had put himself in that company. I still have to review that one, if only for his intro.)

These days, quite a bit of previously uncollected work of his shows up in tiny cheap ebook collections. Often just one or two stories, mainly science fiction, presumably not protected by copyright. I’ve found these little offerings for Kindle useful in terms of getting some historical perspective on Westlake’s early preoccupations and development as a writer, but I can’t honestly say I thought any of them were much good as stories. And neither did he. Man’s gotta know his limitations.

Most of what he wrote for magazines was for experience and to pay bills. Once he could support himself as a novelist alone (with some work on the side for Hollywood), his short story production slacked off quite a bit, but he never completely stopped writing them, along with articles and essays. He never gave up trying to master the form, and he never quite did master it, but there were the odd few exceptions, here and there.

His best shorts frequently involve established series characters, such as Levine and Dortmunder. For obvious reasons–if we agree with Anthony Boucher’s comment up top that Westlake couldn’t easily create believable compelling three-dimensional characters in a short story as he did so often in his novels–it only stands to reason that he’d do his best work at the shorter distance when he already had such a character ready made, so to speak.

The Levine stories, in particular, get stronger with each new entry–because Westlake would keep deepening Levine, remembering what he’d done before with him, and adding to it; fleshing the character and concept out a bit more each time. The end result was a series of brief vignettes that made a negligible impact individually, but were emotionally devastating when read in proper sequence. I don’t even consider that a true anthology–it’s an episodic novel, composed sporadically over the course of several decades.

If you already have a copy of The Curious Facts (a better sharper bit of anthologizing than this, all told, wonder if Lee Wright had a hand in it), I don’t know what you need this one for, unless you’re a completist. Most of the best stories in it appear in that earlier collection (even the capsule review of this anthology in the New York Times agreed with me about One On A Desert Island being his best standalone short, though I question whether the reviewer was aware it had been previously collected).

(The Risk Profession is one of those ten that were in The Curious Facts, as well as Tomorrow’s Crimes, and I am now genuinely baffled as to why it keeps cropping up. That’s three Westlake anthologies it’s appeared in now. I’d forgotten about it being in this one, when I reviewed Tomorrow’s Crimes, which is the only one it should have been in. Westlake must have liked it. I remain unimpressed.)

That Random House collection was long out of print by the time this one came out. That, I suppose, is one reason for its existence. The other was to showcase some later stories (mainly for Playboy). And maybe to remind people that Westlake didn’t just write novels. But it inadvertently served to remind everyone why he primarily wrote novels.

And now I’d best remind myself that I review pretty much everything of his I can get my hands on, and get about my business. There’s still eight stories here I have not yet covered. The first of which is from the 50’s, but did not appear in the earlier Westlake collection. Why? Well, possibly because you can spot the ‘twist’ ending a mile away.

Sinner or Saint: Originally printed in Mystery Digest, in 1958. And there’s no mystery as to its origins, since The Music Man debuted on Broadway at the tail-end of 1957. Mr. Westlake did love the theater (and O. Henry stories).

It’s about a con artist, a charming rogue named Joe Docker, and his criminal Sancho Panza, one Lefty Denker; less brainy than his compatriot, cursed with an unfortunately accurate shifty facial expression, but equipped with a large criminal skill set, which includes the unlocking of locks. Gifted a duo as they are, they got caught and sent to prison, but Joe regards this merely as a hiatus to their careers. A chance to take stock.

So Lefty has been studying the locks at the prison, and figures he can bust them out any time, but Joe wants to take his time, take advantage of the free room, board, and library privileges there. Find the perfect scam, and he does.

There’s a parish wanting a new minister, now the old one has died. There’s a wealthy matron attached to this parish who has a fabulous diamond in her possession. Opportunity knocks at last. He has Lefty let them out of jail, and even has him lock the doors after them, so the prison bulls will waste time searching inside the prison before broadening their search.

There’s a neat bit of business where they break into a closed gas station not far from the prison, and pretend to be running the place–the cops ask Joe if he’s seen the escaped convicts. Joe, properly disguised, regrets to say he hasn’t. Yes, you can definitely see bits and pieces here that would be put to much better use in many a Dortmunder novel.

So of course Joe, posing as the Reverend Mister Amadeus Wimple, with Lefty as a poor lost soul he has taken under his wing, is a huge success as minister, the best in living memory in fact, and in the ensuing months he wins over the skeptical Miss Grace Pettigrew, convincing her to donate her fabulous diamond to a fund to establish a new hospital.

He has a slight complication in the form of an assistant minister sent by the bishop. The new man, Rev. Martin, tells ‘Rev. Wimple’ the archdiocese lost his personnel records, or indeed any record of having dispatched him there–fancy that–but were impressed by all the good things they were hearing about him, and wanted to offer support.

This is all hooey, of course (we were told upfront it was a small denomination–obviously the bishop would know all his ministers). The con man has been conned–the bishop smelled a rat. And instead of calling the cops right away, he dispatched one of his own men to check up on the situation, and they just waited around to see what might transpire. Sure, this could absolutely happen. I mean, why not? Oh never mind.

Joe gets the fabulous diamond put right in his hot little hands, and Lefty is all for scramming, but Joe, enjoying his pastoral duties a mite too much (foot caught in the door, get it?) insists on waiting–until he can convert it into cash through proper legal channels, maximize returns. He tells Lefty to hit the road, they’ll meet up later. Then with just a whisper of regret, he proceeds to deposit the cash–in the account set aside for the hospital. And this, I should add, without even the inducement of Shirley Jones warbling love songs in his ear at the footbridge.

Joe, or should I say Amadeus, has had a chance of heart–and vocation. In studying to be a minister, he has become one. But because the watching law waited for him to abscond with the cash, only to see him donate it for the common good, they have nothing on him but escape from prison, and the previous charges (and he was up for parole in two years anyway). He meekly admits to all his crimes, and waits to be taken back to his cell.

But see, nobody is angry about the con. Everybody still loves him. Miss Pettigrew promises to hire the best lawyers money can buy, Reverend Martin says he’ll be welcomed back as head minister once he gets out, Lefty shows up saying he doesn’t want to be a crook anymore either, and the investigator from the state police says he’s going to make a little call on their behalf. And they all lived happily ever after in the idyllic little town of AreYouFuckingKiddingMe?

Call it a road not taken, and thank God for that. Mind you, O. Henry would have done a beautiful job with it (in the era he was writing in, the plot contrivances would be far easier to justify), and maybe Meredith Willson could have written some punchy numbers for the Broadway version. There are some comparable Warner Bros. flicks from the 30’s–anybody here ever seen Larceny Inc, with Edward G. Robinson?). I’m not say saying stories about reformed criminals never work. This simply isn’t the kind of story Westlake was born to write.

But maybe he had to try and write it first to make sure of that. And maybe in rereading this story, pursuant to it being anthologized, Westlake got an idea for a more deliciously nasty set of swindlers to be featured in a Dortmunder book he was working on at the time. No happy endings for them. Westlake wasn’t much for the grifters–one area of fictive crime where I’d say his buddy Lawrence Block outperformed him.

In fact, I just read a short novel of Block’s where he reforms a small-time hustler, and makes you believe it. But even in a short novel, there’s time to do the groundwork to pull that off. Westlake didn’t have that here, but in due time, he’d come up with a much better story about a heister who reforms. Very much on his own terms, though.

So that’s it for the late 50’s/early 60’s stuff, since the next ten stories, as already mentioned, comprise most of the cream of the earlier anthology (with the head-scratching exception of now thrice-collected The Risk Profession). So for our purposes here, the next story is the title piece, and just like the title piece of the Random House collection (which is also here), it’s one of the weakest stories in the book. Go figure.

A Good Story: More of a forgettable sketch–something that would have worked fine if worked into the fabric of a larger narrative, which might well be what it started out as–background detail for one of Westlake’s Latin American adventures, didn’t make the cut, so he repurposed it for Playboy in 1984. Just a guess.

This American kid named Leon is running a little cantina and private zoo, way up in the Andes, for some local criminal. Been there about eight months now. He’s very pleased with himself, figuring he’ll go home rich when his stint is done. But he’s bored, and these various hot young female tourists come through, and he’s been telling tales out of school.

So now the ‘ice-blond’ traveling companion of some business suit is talking to him in a bored way, acting like she’s in the mood for a quick fling with someone interesting, and he really wants to impress her, and she doesn’t impress easy. She wears Jackie-O sunglasses and everything.

He shows her this little menagerie of animals his boss ships to zoos. He explains, strictly on the QT you understand, that the real business is smuggling cocaine inside monkeys–who are then fed to boa constrictors, so they don’t digest the merchandise, and the snakes of course have a very slow digestive system.

Which he will now find out about first-hand, because the girl and the suit both work for the syndicate, and Leon has already created a lot of legal problems for his employers with his storytelling, and now he’s going to be fed some cocaine envelopes himself, and then it’s feeding time for the boa. End of story.

Okay, how did this kid last even eight months? Sure, okay, he was stupid to go up there in the first place, and overconfidence, combined with a desire to impress the opposite sex, is a frequent attribute of the young. If he was a minor character in a novel, you could buy it. But we learn nothing about him at all, other than his penchant for the gab. He’s every bit as boring as the blonde who lured him in. Again, the set-up isn’t there to justify the pay-off. I felt every bit as bored as the blonde looked. Can’t speak for the snake. Next victim, please.

Breathe Deep: From Playboy again, 1985. The new stories get better as they go–this one probably owes something to the research Westlake did for What’s The Worst That Could Happen? This is too dark for a Dortmunder, though. A dealer name of Chuck is nearing the end of his shift at the casino, when an old man walks up to him, starts engaging him in conversation. The dealer is professional, courteous, but he knows this guy has no money to lose, and therefore no reason to be there.

“Sir,” said the dealer, “I want to give you some friendly advice.” He’d seen past the imperfectly shaved cheeks now, the frayed raincoat, the charity-service necktie. This was an old bum, a derelict, one of the many ancient, alcoholic, homeless, friendless, familyless husks the dry wind blows across the desert into the stone-and-neon baffle of Las Vegas. “You don’t belong here, sir,” he explained. “I’m doing you a favor. Security can get kind of rough, to discourage you from coming back.”

Oh, he knows that, sonny boy–happened to him many times before. But, he explains, he keeps coming back for more lumps. Something about the air in the big casinos–one time he got thrown out, none too gently, via the loading dock out back; he saw all these green oxygen tanks outside. He figures the casino puts a very heavy oxygen mixture into the air, to make their customers more hopeful, energetic, stay up later, gamble more. That’s what kept him coming back, over and over, until his string ran out. He produces a can of lighter fluid and starts squirting it around.

The dealer insists they don’t do that with the oxygen, frantically presses the button on the floor that summons security, and tells the old man they’re coming for him. The old man says that’s good–he wants to have some company on his trip. He lights a kitchen match.

Sure, just a vignette (not even five full pages), but a decent one. An even better one next.

Love In the Lean Years: Again from Playboy, in 1992, and proof positive that Westlake could still write a short story worth reading–and that his creative energies were dramatically rekindled during the 90’s. There was, you might say, much in the era he found inspiring, if not necessarily encouraging.

Charles Dickens knew his stuff, you know. Listen to this: “Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen nineteen six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery.”

Right on. You adjust the numbers for inflation and what you’ve got right there is the history of Wall Street. At least, so much of the history of Wall Street as includes me: seven years. We had the good times and we lived high on that extra daily sixpence, and now we live day by day the long decline of shortfall. Result misery.

Where did they all go, the sixpences of yesteryear? Oh, pshaw, we all know where they went. You in Gstaad, him in Aruba, her in Paris and me in the men’s room with a sanitary straw in my nose. We know where it went, all right.

That’s one of the two narrators, Bruce Kimball, an account executive with a brokerage firm. The other narrator (they alternate telling us the story) is Stephanie Morwell, 42, attractive widow (lots of time and expense involved in maintaining that), living off various investments her husbands (yes, plural) left behind, hence her relationship with Bruce, which turns amorous, partly because she likes him, and partly because she (incorrectly) assumes he’s loaded, as he (incorrectly) assumes of her. Yes, again there’s something of an O.Henry feel to the tale at hand, but these two ain’t Jim and Della, and no magi are in the offing.

Cupid capriciously blasts his bolts at this mercenary mingling of fading fortunes. The sex is great, compatibility is high, and they are married in a sconce, happily so, to the great surprise of both. But Stephanie has a little secret Bruce discovers when trying, manfully, to straighten out her tangled financial affairs. More tangled than he had imagined. She’s had quite a lot of husbands, you see. And she took out large life insurance policies on all of them. And each of them just happened to perish unexpectedly about a year after each policy took effect. And she’s taken one out on him now.

Bruce is no Black Widow’s brunch, no matter how good she is in bed. He takes out an equally generous policy on her, and awaits the proper moment. But Cupid is in a joking mood, and Stephanie realizes she really does love this one, can’t bring herself to do him in, they’ll just have to make ends meet somehow, economize more, and to that end she opts to cancel the policy she took out on life, but that’s when she finds out about the one he took out on hers. That’s where it ends, with Stephanie absorbing the bitter truth that turnabout is fair play. We never learn who won out in the end, but it sure wasn’t True Love.

Maybe a bit too bloodless? The point, of course, was to turn O. Henry on his head, as well as to revisit one of Westlake’s own stories (Never Shake a Family Tree, also present in this volume), and to suggest that these are not romantic times we are living in, certainly not those of us who are addicted to conspicuous consumption. Hey, anybody know how much Trump is insured for? Well, the next story is a positive Valentine’s Day Card by comparison, though it actually celebrates a different holiday.

Last-Minute Shopping: First appeared in the New York Times in 1993. A cop named Keenan braces a crook named O’Brien, on Christmas Eve, no less. But not to arrest him–he needs a little help with his love life. He broke up with his girlfriend (a waitress) a while back, and now she’s just called him (the holidays being such a lonely time for the unattached), saying she’s been thinking about him for weeks, and they should get together after her shift ends, around midnight.

He realizes she must have gotten him a gift. But being so hurt and angry over the break-up, assuming it was permanent, he didn’t get her anything. He’s got one hour to get her something really nice, and the jeweler’s is closed. Hence O’Brien. Who has broken into said jeweler’s more than once, Keenan has good reason to believe.

O’Brien objects roundly, fearing entrapment, but Keenan insists this is on the up and up. It’s not strictly legal, but it’s not theft, since he’ll be leaving cash there for whatever item he chooses for his lovelorn Laurie. He just needs a little expert assistance getting inside the place. And come some future occasion, when O’Brien needs a favor–and that day will surely come–O’Brien has little choice but to agree. And Keenan says O’Brien can pick up something for his girlfriend as well–he’ll also have to pay for it. You can’t give stolen goods for a Christmas present. It is known.

So they break in, keeping the lights off inside, since neither can afford to get caught. Keenan finds a lovely bracelet (gold filigree inlaid with garnets, so much more character than diamonds, I’ve always thought), and O’Brien picks out a brooch that will match his Grace’s eyes, and strangely enough has more than enough cash to pay for it as well.

So at Grace’s place, shortly prior to getting laid (oh grow up, half the Christmas songs you hear at the mall in December are about premarital nookie), O’Brien explains to a gratified yet suspicious Grace how exactly he got the cash to pay for her gift. He picked the sentimental cop’s pocket. Flatfoot didn’t even know how much he had on him–must have cleaned out his bank account, to make sure he had enough for whatever peace offering he picked. Like many another successful burglar, O’Brien has great night vision. Which he will now turn to less mercenary ends. Joyeux Noel.

I think O. Henry might have liked this one. But would have pretended he didn’t, in case there were cops listening in. And what follows is yet another Christmas-themed short involving larceny, but not romantic in the least. Well, science fiction so rarely ever is.

The Burglar and the Whatsit: From Playboy, 1996. A burglar named Jack, posing as Santa Claus in order to rob people’s apartments unsuspected, is accosted by a drunken inventor, so drunk that he actually believes this guy in the red suit with a bag full of (stolen) goodies is the real ‘Sanity Clause’ as he insists on putting it. He figures the Big Guy would be the one to ask–he’s invented something. Something pretty good, he thinks. But he was drunk when he made it, and he can’t remember what it does. This happens to him a lot, but he usually leaves himself a note on his computer to remind him. This time somebody stole the computer, would you believe it? Jack has nothing to say to that.

Jack really has no idea what this weird little device could be–it’s some kind of robot, a box on wheels, and all these antennae sprout out of it, while it makes these whirring noises. It does not seem to like Jack at all. The inventor talks about how laughable the burglar alarms in his building are. Jack silently concurs with that.

So they basically try to figure out what the inventor might have wanted to invent, and when Jack, responding to the inventor’s indignation over the inadequate alarms in the building, says it’s really hard to find a good one, the inventor lights up like his whatsit, and says that’s it. It’s a burglar alarm–that can actually identify burglars, before they’ve finished burgling–and then call the police. There’s a knock on the door. The inventor wonders who that could be.

And again, I am reminded why Westlake never really excelled at science fiction, unless he had some idea he really needed to get across. Though this could have made a decent enough concept for a Twilight Zone. Well, maybe half a Twilight Zone. Probably Rod Serling would have insisted the whatsit have disintegrator beams or something.

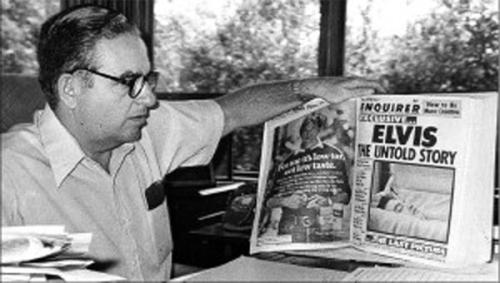

And now comes my favorite story that is unique to this collection–partly because it’s a sequel to Trust Me On This and captures the madcap spirit of that book rather more effectively than the second Sara Joslyn novel, but mainly because there’s a dog in it. Oh Mr. Westlake, you shouldn’t have. Seriously, he shouldn’t, because this is a murder mystery, and the dog is the victim. Also a major celebrity. Who answers (well, formerly) to the rather unsonorous name of–

Skeeks: From Playboy (Again? Did they have him on retainer?), 1995. The protagonist of the piece is Boy Cartwright, the sneering smarmy supercilious English rival to Sara Joslyn and Jack Ingersoll, the Uriah Heep of the scandal sheet. He is still star reporter for the Weekly Galaxy, (No mention of ‘Massa’ so this would definitely have taken place well after the first novel). A man so utterly without scruples of any kind that were he not a fictional character he would undoubtedly already be on the Trump transition team.

The second and final Joslyn book came out in 1994. Boy was in it (briefly). Good bet Westlake would have come up with some secondary storylines to reintroduce him, remind people what an unmitigated cad he is, that ultimately didn’t fit into the finished work. Or else he just had this idea for another Hollywood satire, Boy was clearly the man for the job, and he was fresh in his creator’s mind.

In any event, this is the longest story in the collection, 22 pages. Not novella length, but more room than Westlake normally had to work with in this format, and as a result it feels much more like an actual story, as opposed to a sketch. Though Boy himself is little more than a caricature, albeit vividly drawn. So in spite of my above attempts to explain the existence of this tale, I must yet inquire–Mr. Westlake–of all the beloved supporting characters from past novels you might have tapped for a leading role–all the Handy McKays, the J.C. Taylors, the Brenda & Ed Mackeys–why him? Well, let’s try and figure that out.

Boy Cartwright awakens like the dead (to conscience, anyway) from a drunken revel with a subordinate named Trixie (“or so she claimed.”) His phone rings–it’s Mr. Scarpnafe, some high muckity muck with the Galaxy. He informs Boy that Skeeks is dead, as if Boy is supposed to know what that means. Boy pretends to know what that means.

He is to fly to Los Angeles at once, assemble a team, to cover the funeral, assemble vital statistics regarding the deceased, and above all to get The Body in the Box, which as you should all know by now means a picture of some grand personage in his or her coffin for the front page. These are frequently very tricky to obtain, as has been sufficiently well covered elsewhere. Skeeks shall prove to be no exception. But who, pray tell, is Skeeks?

On the plane coming out, Boy had been brought up to speed on the late Skeeks, who had been, it seemed, a lovable German Shepherd, as if there could be any such a thing. For three years Skeeks had portrayed the adorable pooch on an extremely successful sitcom, and when the human male lead of that show decided to throw it all in for the glories of failure as a motion picture star, the mail bemoaning the disappearance of Skeeks from the nation’s screens (they’re that stupid, and yet they can read and write, marveled Boy) was so overwhelming (the word avalanche was used in all press releases on the subject) that the network brought Skeeks back the next season with his very own sitcom, called Skeeks, in which he portrayed the dog in a man-and-dog vaudeville act. The idea at the heart of this series–that there is, at this moment, in the secondary cities of America, a thriving circuit of vaudeville theaters–was not the most outlandish suggestion ever made on television, and it was accepted without a murmur, as was Skeeks’ partner on Skeeks, a comedian named Bill Terry, who when sober could juggle, sing, ride a unicycle and remember jokes.

The funeral shall be conducted at Forest Lawn’s Wee Kirk o’ the Heather, “the largest send-off there since that tramp what’s-her-name.” I assume the narrator doesn’t refer to Lassie, since she was a paragon of virtue, and also invariably portrayed by male collies.

(This is all very dated, you know–like worse than the notion that there’s an active vaudeville circuit in late 20th century America. There had been no American primetime network shows with a dog as the protagonist since Lassie went off the air in 1975. None that lasted, anyway. Might as well have said the funeral was for Ed Sullivan, and he was still on TV each week with Senor Wences and Topo Gigio-[I wish].

Dogs could still have roles on sitcoms by then, sure. But when Frasier went off the air, they didn’t do a spin-off about the misadventures of Eddie Spaghetti. Which would have been watched religiously in my house, I can tell you. And we will watch anything with a lovable German Shepherd in it. “As if there could be any such a thing.” I do hope that line was worth the extra stint in Purgatory, Mr. Westlake.)

Now the problem with giving Skeeks the traditional Galaxy treatment, as opposed to your usual dead celebrity, is that being a dog, he’d led a very boring life away from work. No scandalous affairs (he had, in fact, been neutered as a puppy), no catty ex-wives (well, obviously), no threats to walk over outrageous salary demands, no racist remarks, no drunken binges (at least a famous feline might have had some catnip-related indiscretions), no cults, no stints in rehab. He just lived quietly at home with his caretaker/housekeeper Mayjune Kent, a former model who had been horribly scarred (The Phantom of the Opera would faint at the sight of her) by acid thrown by a crazed admirer, whom she had subsequently run over with a car. They were said to be very close, Skeeks and Mayjune–the scars don’t bother him at all–but no sex tapes, so that’s a dead end.

But at a local restaurant, an informant who works at the veterinary clinic Skeeks was pronounced dead at has a terrible secret to reveal–it was murder! (dramatic music please). The vets are hushing it up because they’re afraid they’ll get blamed. But no question at all, somebody poisoned Skeeks, idol of a grieving nation. And Boy Cartwright, crusading reporter, fully intends to find out whodunnit, because that would make a smashing story.

So let me just cut to the chase, since there’s one more story to review after this. After a bit of sniffing around (heh), and several successive failures to obtain the required coffin photo, Boy winds up inside the former Skeeks residence, and overhears a conversation between Mayjune Kent and Sherry Cohen, producer on the show, and girlfriend to Bill Terry, Skeeks’ sidekick (he’s reportedly none too happy about that).

Mayjune has cracked the case–she knows Sherry poisoned Skeeks. She knows precisely why Sherry would do such a thing. A depressed and overshadowed Bill is slowly drinking himself to death. The only way to save him was to make him a star in his own right. The show’s ratings are such that the network would look for some way to save it in the event of Skeeks’ untimely demise, and promote Bill to star. (It somehow never occurred to Sherry that there’s other German Shepherds working in showbiz. I mean, how many dogs have played Kommissar Rex by now? Komissar Who, you ask? Dumkopfs.)

But surely Mayjune could be mistaken in her suspicions? And anyway, so what if she isn’t?

“Mayjune, he was an animal! You can’t say he–besides, why say it was me? I mean, if it even happened.”

“I didn’t do it, and Bill doesn’t have the guts, and who else is there? You did it for love, Sherry. I know you did, for the love of Bill. But I loved Skeeks, and that’s why you’re going to die now.”

Jumping to her feet, Sherry cried, “What are you talking about? I’m not going to die!”

“We both are, Sherry. Skeeks was the only one in my life. You took him away from me. I have no reason to live.”

“Mayjune! For God’s sake, what have you done?”

“The same poison you used,” Mayjune said, as calm as voice mail. “It’s in the cookies, and the tea. We both have less than half an hour to live.”

Sherry is forced to accept that it’s too late to do anything about the poison, and she and Mayjune somberly await their impending demise, while Boy tiptoes over to the fridge to get himself a snack to tide him over until it’s over. Mayjune mentioned having a lovely photograph of Skeeks in his coffin that she snapped herself at the vet’s; it’s right there in the other room, so he is victorious on all fronts. He’ll call the police after he’s safely away from there, and after he’s called his scoop in to the Galaxy, of course. In the meantime, he starts working on the lead-in to his story. “They did it for love.” Something Boy Cartwright could never understand, but hum a few bars…

So if I’d happened to pick up the issue of Playboy this first appeared in (for the articles, of course) I’d consider it well worth the inflated cover price. (I never did much care for the naked pictures they no longer feature there, so obvious and banal, though there was this red-headed firewoman from Texas–).

And as with his other efforts featuring the delirious denizens of the Galaxy, he achieves this odd effect, where you both rejoice in the amoral escapades of the reporters, and at the same time, mourn for the human condition, such as it is. I still believe Westlake was afraid of dogs, hence his almost W.C. Fieldsian cynicism towards them (as much a self-conscious posture as Fields’ supposed dislike of children–in both cases, the real target is cheap sentiment), but under all that, you still somehow feel that Mayjune Kent, as absurd as the motive and manner of her self-inflicted demise may be, is still the only human in this story who is worth a tinker’s damn.

A dog doesn’t care what you look like. Skeeks only saw and smelled a person he loved. She saw him the same way, caring nothing for his celebrity, for the image of him projected on TV–just for the image of her true self she saw reflected in his guileless eyes. And she knew that for all his fame, the law could never properly avenge him. Because to the law, and the holding company that owned (and heavily insured) him, he was only a valuable piece of property. And the backstory has already established that Mayjune is capable of murder, when you attack her self-image.

And strangely, it’s through the malevolent machinations of a man who never loved anybody, who is completely unmoved by the spectacle unfolding before him, that the world will learn of this poignant sacrifice she made. No doubt soon to be a movie of the week. Actually, I don’t think they were doing those on the networks by the Mid-90’s either. Maybe on Lifetime? Or E! Actresses will be lined up from Burbank to Fresno to play Mayjune. Scars! Prosthetic makeup! Emmy, here I come!

So that leaves just one more story, fittingly enough entitled–

Take it Away: From 1997, published in an anthology called The Plot Thickens (Lawrence Block had something in it too), the proceeds of which went to charity, but a critic must of course show none.

An FBI agent on a stakeout pops into a Burger Whopper franchise (pretty sure there’d be a lawsuit if anybody started a franchise by that name) for a quick bite, and the guy behind him starts chatting him up in ways that subtly suggest he knows the guy he’s talking to is an FBI agent on a stakeout. The Fed is suspicious, but thinks maybe he’s imagining it. They’re after this sneaky French art smuggler. Well, guess what? The guy in line behind him was the smuggler, playing with him for laughs, taunting him with his mastery of disguise and his ability to assume a perfect American accent. End of story.

Okay, that was short shrift, but I’m over 6,000 words, and I did not like that one at all. The Times reviewer loved it, and she gave it all of one sentence. This is probably the longest review Take it Away will ever get.

There’s maybe ten very good stories in this collection of eighteen written over the course of maybe thirty years. A few others that are decent enough little thumbnail sketches. And nothing that comes remotely close to the best work this writer was capable of.

But as I said when reviewing The Curious Facts, it may well be that Westlake needed to keep trying to write that perfect short story that just simply was not in him, in order to prepare himself for the kind of writing he was meant for. In chapter after chapter of his best novels (and even some of his lesser ones), you do in fact see that perfect short story–bundled into a larger narrative. By working in miniature, on short deadlines, writing to the ever-dwindling magazine market, he learned how to put a lot of story into a very small space. But he needed that extra space a novel affords to make his characters breathe. So that we’d give a damn when they stopped breathing.

But suppose his characters were writers, like himself? Could he make us care about them? Time to find out. And if it doesn’t work, well, better get out the hook.